conflict of interest

They say that minds are like parachutes – they function only when open. Having an open mind means being receptive to new and different ideas or the opinions of others.

I am regularly accused of lacking this quality. Most recently, an acupuncturist questioned whether acupuncture-sceptics, and I in particular, have an open mind. Subsequently, an interesting dialogue ensued:

___________________________________________________________

Tom Kennedy on Wednesday 01 August 2018 at 19:27

the EVIDENCEBASEDACUPUNCTURE site you recommend quotes the Vickers meta-analysis thus:

“A meta-analysis of 17,922 patients from randomized trials concluded, “Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo.”

Pity that they forgot a bit. The full conclusion reads:

“Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo. However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture.”

AND YOU TRY TO LECTURE US ABOUT AN OPEN MIND?

@Edzard I’m not sure I understand your point. ‘However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture.’ Perhaps the full conclusion should always be quoted, but I don’t think that addendum changes the context significantly. Acupuncture has been shown to be more than a placebo in a large meta-analysis (when compared to arguably active sham controls). The authors put it well I think, in the ‘Interpretation’ section:

‘Our finding that acupuncture has effects over and above sham acupuncture is therefore of major importance for clinical practice. Even though on average these effects are small, the clinical decision made by doctors and patients is not between true and sham acupuncture, but between a referral to an acupuncturist or avoiding such a referral. The total effects of acupuncture, as experienced by the patient in routine practice, include both the specific effects associated with correct needle insertion according to acupuncture theory, non-specific physiologic effects of needling, and non-specific psychological (placebo) effects related to the patient’s belief that treatment will be effective.’

Compare this to Richard’s comment here, for example: ‘Of course the effects of ‘acupuncture’ (if any) are due to placebo responses (and perhaps nocebo responses in some cases). What else?’. And your post tile includes the line ‘the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo’. These are the kinds of comment that to me seem closed-minded in the face of some significant evidence.

edzard on Thursday 02 August 2018 at 12:46

“Perhaps the full conclusion should always be quoted…”

YES, IF NOT, IT’S CALLED ‘BEING ECONOMICAL WITH THE TRUTH’

“…I don’t think that addendum changes the context significantly.”

IT’S NOT AN ADDENDUM, BUT PART OF THE CONCLUSION; AND YOU ARE WRONG, FOR ME, IT CHANGES A LOT.

“…your post tile includes the line ‘the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo’.”

BECAUSE THIS IS WHAT THE PAPER DISCUSSED IN THAT PARTICULAR POST IMPLIED.

‘IT’S CALLED ‘BEING ECONOMICAL WITH THE TRUTH’’

The title of this post is: ‘Yet another confirmation: the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo’. That’s also being economical with the truth I think. You argue ‘BECAUSE THIS IS WHAT THE PAPER DISCUSSED IN THAT PARTICULAR POST IMPLIED’, but is it? The authors state ‘Future studies are needed to confirm or refute any effects of acupuncture in acute stroke’, and that would have been a much more balanced headline. You clearly imply here that it has been CONFIRMED that the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo, and that this trial is further confirmation. This is misleading at best. Yes, you add in brackets ‘(for acute stroke)’ at the end of the post, but why not in the title, unless you want to give the impression this is true for acupuncture in general

Edzard on Thursday 02 August 2018 at 14:09

my post is about critical evaluation of the published literature.

and this is what follows from a critical evaluation of this particular article.

I am not surprised that you cannot follow this line of reasoning.

could it be that the lack of an open mind is not my but your problem

‘could it be that the lack of an open mind is not my but your problem?’

Who knows, maybe the problem is both of ours? I’m open to all possibilities!

VERY GOOD!

ok, let’s have a look.

you 1st: learnt acupuncture [a therapy that relies on a 2000 year old dogma], never published anything negative about it, never used any other therapeutic modality, even treated my own daughter with acupuncture when she suffered from infant colic, earn my livelihood by doing acupuncture.

[I MIGHT BE WRONG HERE, AS I DON’T KNOW ALL THAT MUCH ABOUT YOU, SO PLEASE CORRECT ME]

me next: studied acupuncture during my time in med school, used it occasionally, learnt to use dozens of other therapeutic modalities, published lots about acupuncture based on the current evidence [this means that some conclusions – even of my Cochrane reviews – were positive but have since changed], worked with acupuncturists from across the globe, published one book about acupuncture together with several acupuncture fans, now dedicate my time to the critical analysis of the literature and bogus claims, have no conflicts of interest.

[IN CASE YOU KNOW MORE RELEVANT THINGS ABOUT ME, PLEASE ADD]

@Edzard Your summaries seem to be more or less accurate. However, a) I wouldn’t agree with your use of the term ‘dogma’; b) I haven’t published any scientific papers, but I’ve acknowledged various problems in the acupuncture field through informal pieces; c) I’ve used other CAM modalities, and I’ve directly or indirectly experienced many conventional modalities; d) I only earn part of my livelihood by doing acupuncture. Yes, my background makes it more likely that I’ll be biased in favour of acupuncture. But your credentials in no way guarantee open-mindedness on the subject, and personally I don’t see that displayed often on this blog. It still makes for interesting and stimulating reading though.

what problems in the acupuncture field have you acknowledged through informal pieces?

can you provide links?

I want to get a feel for the openness of your mind.

“…your credentials in no way guarantee open-mindedness on the subject, and personally I don’t see that displayed often on this blog.”

1) you seem to forget that blog-posts are not scientific papers, not even close.

2) you also forget that my blog is dedicated to the CRITICAL assessment of alt med.

finally, what would make you think that someone has an open mind towards acupuncture, if not the fact that someone has a track record of publishing positive conclusions about it when the evidence allows?

remember: an open mind should not be so open that your brain falls out!

Tom Kennedy on Friday 03 August 2018 at 11:20

Here’s one example: https://www.tomtheacupuncturist.com/blog/2017/2/24/does-acupuncture-really-work

‘what would make you think that someone has an open mind towards acupuncture, if not the fact that someone has a track record of publishing positive conclusions about it when the evidence allows?’

I think there’s plenty of evidence that allows for positive conclusions about acupuncture, but you don’t report these. I understand the slant of this blog, but I’d say it comes across as ‘negative assessment’ rather than ‘critical assessment’. Perhaps you’ll argue that your critical assessment has led you to a negative assessment? I’ll just have to disagree that that’s a fair and open-minded summary of the evidence.

Out of interest, can I ask what your acupuncture training involved (hours, theory, clinic time etc.)?

I am sorry to say that I see no critical evaluation in the post you linked to.

” I’d say it comes across as ‘negative assessment’ rather than ‘critical assessment’.

have you noticed that criticism is often experienced as negative to the person(s) it is aimed at?

‘I am sorry to say that I see no critical evaluation in the post you linked to’

I’ll just have to live with that. I feel as though it acknowledges some of the problems in the acupuncture world, in an attempt at balance. I don’t feel your posts aim for balance, but as you said, a blog isn’t a scientific paper so it’s your prerogative to skew things as you see fit

Edzard on Friday 03 August 2018 at 13:18

it seems to me that the ‘screwing things as you see fit’ is your game.

____________________________________________________________________

This exchange shows how easily I can be provoked to get stroppy and even impolite – I do apologise.

But it also made me wonder: how can anyone be sure to have an open mind?

And how can we decide that a person has a closed mind?

We probably all think we are open minded, but are we correct?

I am not at all sure that I know the answer. It obviously depends a lot on the subject. There are subjects where one hardly needs to keep an open mind and some where it might be advisable to have a closed mind:

- the notion that the earth is flat,

- flying carpets,

- iridology,

- reflexology,

- chiropractic subluxation,

- the vital force,

- detox,

- homeopathy.

No doubt, there will be people who even disagree with this short list.

Something that intrigues me – and I am here main ly talking about alternative medicine – is the fact that I often get praised by people who say, “I do appreciate your critical stance on therapy X, but on my treatment Y you are clearly biased and unfairly negative!” To me, it is an indication of a closed mind, if criticism is applauded as long as it does not tackle someone’s own belief system.

On the subject of homeopathy, Prof M Baum and I once published a paper entitled ‘Should we maintain an open mind about homeopathy?’ Its introduction explains the problem quite well, I think:

Once upon a time, doctors had little patience with the claims made for alternative medicines. In recent years the climate has changed dramatically. It is now politically correct to have an open mind about such matters; “the patient knows best” and “it worked for me” seem to be the new mantras. Although this may be a reasonable approach to some of the more plausible aspects of alternative medicine, such as herbal medicine or physical therapies that require manipulation, we believe it cannot apply across the board. Some of these alternatives are based on obsolete or metaphysical concepts of human biology and physiology that have to be described as absurd with proponents who will not subject their interventions to scientific scrutiny or if they do, and are found wanting, suggest that the mere fact of critical evaluation is sufficient to chase the healing process away. These individuals have a conflict of interest more powerful than the requirement for scientific integrity and yet defend themselves by claiming that those wanting to carry out the trials are in the pocket of the pharmaceutical industry and are part of a conspiracy to deny their patients tried and tested palliatives….

END OF QUOTE

And this leads me to try to define 10 criteria indicative for an open mind.

- to be free of conflicts of interest,

- integrity,

- honesty,

- to resist the temptation of applying double standards,

- to have a track record of having changed one’s views in line with the evidence,

- to not cling to overt absurdities,

- to reject conspiracy theories,

- to be able to engage in a meaningful dialogue with people who have different views,

- to avoid fallacious thinking,

- to be willing to learn more on the subject in question.

I would be truly interested to hear, if you have further criteria, or indeed any other thoughts on the subject.

This recent announcement by the Society of Homeopaths (SoH), the organisation of non-doctor homeopaths in the UK, seems worthy of a short comment. Here is the unabbreviated text in question:

Two new members have been appointed to the Society’s Public Affairs (PAC) and Professional Standards (PSC) committees for three-year terms of office.

Selina Hatherley RSHom is joining the PAC. She has been a member since 2004 and works in three multi-disciplinary practices in Oxfordshire and previously ran a voluntary clinic working with people with drug, alcohol and mental health issues for 12 years. She has also been involved in the acute trauma clinics following the Grenfell Tower fire in 2017.

New to the PSC is Lynne Howard. She became a RSHom in 1996 and runs a practice in three locations in east London and a major London hospital. She specialises in pregnancy, birth and mother-and-baby issues.

“Following an open and comprehensive appointment process, we are delighted to welcome Selina and Lynne ‘on-board’ as brand-new committee members who will bring new ideas, experiences and knowledge to the society,” said Chief Executive Mark Taylor.

END OF QUOTE

It seems to me that the SoH might be breaching its very own Code of Ethics with these appointments.

1) Lynne Howard BA, LCH, MCH, RSHom tells us on her website that she has been practising homeopathy for 25 years, she has run many children’s clinics and is a registered CEASE practitioner with a special interest in fertility and children’s health.

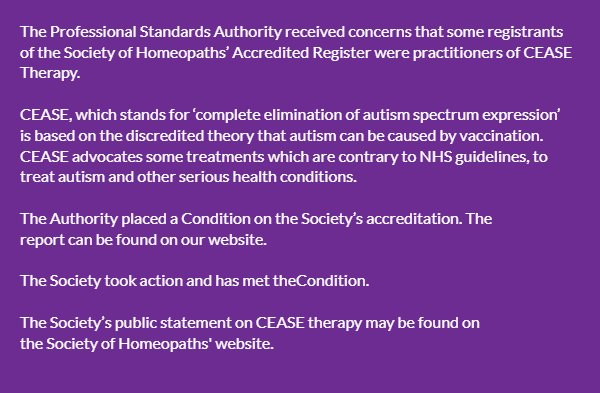

CEASE therapy has been discussed before on this blog. It is highly unethical and the SoH have been warned about it before. They even pretended to take the warning seriously.

2) Selina Hatherley has a website where she tells us this: In 2011 I trained as a Vega practitioner – enabling me to use the Vega machine to test for food sensitivity and allergens. I use homeopathic remedies to support the findings and to help restore good health… I am a registered member of the Society of Homeopaths – the largest organisation registering professional homeopaths in Europe, I abide by their Code of Ethics and Practice and am fully insured.

2) Selina Hatherley has a website where she tells us this: In 2011 I trained as a Vega practitioner – enabling me to use the Vega machine to test for food sensitivity and allergens. I use homeopathic remedies to support the findings and to help restore good health… I am a registered member of the Society of Homeopaths – the largest organisation registering professional homeopaths in Europe, I abide by their Code of Ethics and Practice and am fully insured.

Vega, or electrodermal testing for allergies has been evaluated by the late George Lewith (by Jove not a man who was biased against such things) and found to be bogus. Here are the conclusions of his study published in the BMJ: “Electrodermal testing cannot be used to diagnose environmental allergies.” That’s pretty clear, I think. As the BMJ is not exactly an obscure journal, the result should be known to everyone with an interest in Vega-testing. And, of course, disregarding such evidence is unethical.

But perhaps, in homeopathy, ethics can be diluted like homeopathic remedies?

Perhaps the SoH’s Code of Ethics even allows such behaviour?

Have a look yourself; here are the 16 core principles of the SoH’s CODE OF ETHICS:

1.1 Put the individual needs of the patient first.

1.2 Respect the privacy and dignity of patients.

1.3 Treat everyone fairly, respectfully, sensitively and appropriately without discrimination.

1.4 Respect the views of others and, when stating their own views, avoid the disparagement of others either professionally or personally.

1.5 Work to foster and maintain the trust of individual patients and the public.

1.6 Listen actively and respect the individual patient’s views and their right to personal choice.

1.7 Encourage patients to take responsibility for their own health, through discussion and provision of information.

1.8 Comprehensively record any history the patient may give and the advice and treatment the registered or student clinical member has provided.

1.9 Provide comprehensive clear and balanced information to allow patients to make informed choices.

1.10 Respect and protect the patients’ rights to privacy and confidentiality.

1.11 Maintain and develop professional knowledge and skills.

1.12 Practise only within the boundaries of their own competence.

1.13 Respond promptly and constructively to concerns, criticisms and complaints.

1.14 Respect the skills of other healthcare professionals and where possible work in cooperation with them.

1.15 Comply with the current statutory legislation in relation to their practice as a homeopath of the country, state or territory where they are practising.

1.16 Practise in accordance with the Core Criteria for Homeopathic Practice and the Complementary and Natural Healthcare National Occupational Standards for Homeopathy.

______________________________________________________

I let you decide whether or not the code was broken by the new appointments and, if so, on how many accounts.

The Royal College of Chiropractors (RCC), a Company Limited by guarantee, was given a royal charter in 2013. It has following objectives:

- to promote the art, science and practice of chiropractic;

- to improve and maintain standards in the practice of chiropractic for the benefit of the public;

- to promote awareness and understanding of chiropractic amongst medical practitioners and other healthcare professionals and the public;

- to educate and train practitioners in the art, science and practice of chiropractic;

- to advance the study of and research in chiropractic.

In a previous post, I pointed out that the RCC may not currently have the expertise and know-how to meet all these aims. To support the RCC in their praiseworthy endeavours, I therefore offered to give one or more evidence-based lectures on these subjects free of charge.

And what was the reaction?

Nothing!

This might be disappointing, but it is not really surprising. Following the loss of almost all chiropractic credibility after the BCA/Simon Singh libel case, the RCC must now be busy focussing on re-inventing the chiropractic profession. A recent article published by RCC seems to confirm this suspicion. It starts by defining chiropractic:

“Chiropractic, as practised in the UK, is not a treatment but a statutorily-regulated healthcare profession.”

Obviously, this definition reflects the wish of this profession to re-invent themselves. D. D. Palmer, who invented chiropractic 120 years ago, would probably not agree with this definition. He wrote in 1897 “CHIROPRACTIC IS A SCIENCE OF HEALING WITHOUT DRUGS”. This is woolly to the extreme, but it makes one thing fairly clear: chiropractic is a therapy and not a profession.

So, why do chiropractors wish to alter this dictum by their founding father? The answer is, I think, clear from the rest of the above RCC-quote: “Chiropractors offer a wide range of interventions including, but not limited to, manual therapy (soft-tissue techniques, mobilisation and spinal manipulation), exercise rehabilitation and self-management advice, and utilise psychologically-informed programmes of care. Chiropractic, like other healthcare professions, is informed by the evidence base and develops accordingly.”

Many chiropractors have finally understood that spinal manipulation, the undisputed hallmark intervention of chiropractors, is not quite what Palmer made it out to be. Thus, they try their utmost to style themselves as back specialists who use all sorts of (mostly physiotherapeutic) therapies in addition to spinal manipulation. This strategy has obvious advantages: as soon as someone points out that spinal manipulations might not do more good than harm, they can claim that manipulations are by no means their only tool. This clever trick renders them immune to such criticism, they hope.

The RCC-document has another section that I find revealing, as it harps back to what we just discussed. It is entitled ‘The evidence base for musculoskeletal care‘. Let me quote it in its entirety:

The evidence base for the care chiropractors provide (Clar et al, 2014) is common to that for physiotherapists and osteopaths in respect of musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions. Thus, like physiotherapists and osteopaths, chiropractors provide care for a wide range of MSK problems, and may advertise that they do so [as determined by the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA)].

Chiropractors are most closely associated with management of low back pain, and the NICE Low Back Pain and Sciatica Guideline ‘NG59’ provides clear recommendations for managing low back pain with or without sciatica, which always includes exercise and may include manual therapy (spinal manipulation, mobilisation or soft tissue techniques such as massage) as part of a treatment package, with or without psychological therapy. Note that NG59 does not specify chiropractic care, physiotherapy care nor osteopathy care for the non-invasive management of low back pain, but explains that: ‘mobilisation and soft tissue techniques are performed by a wide variety of practitioners; whereas spinal manipulation is usually performed by chiropractors or osteopaths, and by doctors or physiotherapists who have undergone additional training in manipulation’ (See NICE NG59, p806).

The Manipulative Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (MACP), recently renamed the Musculoskeletal Association of Chartered Physiotherapists, is recognised as the UK’s specialist manipulative therapy group by the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists, and has approximately 1100 members. The UK statutory Osteopathic Register lists approximately 5300 osteopaths. Thus, collectively, there are approximately twice as many osteopaths and manipulating physiotherapists as there are chiropractors currently practising spinal manipulation in the UK.

END OF QUOTE

To me this sounds almost as though the RCC is saying something like this:

- We are very much like physiotherapists and therefore all the positive evidence for physiotherapy is really also our evidence. So, critics of chiropractic’s lack of sound evidence-base, get lost!

- The new NICE guidelines were a real blow to us, but we now try to spin them such that consumers don’t realise that chiropractic is no longer recommended as a first-line therapy.

- In any case, other professions also occasionally use those questionable spinal manipulations (and they are even more numerous). So, any criticism of spinal manipulation should not be directed at us but at physios and osteopaths.

- We know, of course, that chiropractors treat lots of non-spinal conditions (asthma, bed-wetting, infant colic etc.). Yet we try our very best to hide this fact and pretend that we are all focussed on back pain. This avoids admitting that, for all such conditions, the evidence suggests our manipulations to be worst than useless.

Personally, I find the RCC-strategy very understandable; after all, the RCC has to try to save the bacon for UK chiropractors. Yet, it is nevertheless an attempt at misleading the public about what is really going on. And even, if someone is sufficiently naïve to swallow this spin, one question emerges loud and clear: if chiropractic is just a limited version of physiotherapy, why don’t we simply use physiotherapists for back problems and forget about chiropractors?

(In case the RCC change their mind and want to listen to me elaborating on these themes, my offer for a free lecture still stands!)

Needle acupuncture in small children is controversial, not least because the evidence that it works is negative or weak, and because small children are unable to consent to the treatment. Yet it is recommended by some acupuncturists for infant colic. This, of course, begs the questions:

- Does the best evidence tell us that acupuncture is effective for infant colic?

- Are acupuncturists who recommend acupuncture for this condition responsible and ethical?

This systematic review and a blinding-test validation based on individual patient data from randomised controlled trials was aimed to assess its efficacy for treating infantile colic. Primary end-points were crying time at mid-treatment, at the end of treatment and at a 1-month follow-up. A 30-min mean difference (MD) in crying time between acupuncture and control was predefined as a clinically important difference. Pearson’s chi-squared test and the James and Bang indices were used to test the success of blinding of the outcome assessors [parents].

The investigators included three randomised controlled trials with data from 307 participants. Only one of the included trials obtained a successful blinding of the outcome assessors in both the acupuncture and control groups. The MD in crying time between acupuncture intervention and no acupuncture control was -24.9 min at mid-treatment, -11.4 min at the end of treatment and -11.8 min at the 4-week follow-up. The heterogeneity was negligible in all analyses. The statistically significant result at mid-treatment was lost when excluding the apparently unblinded study in a sensitivity analysis: MD -13.8 min. The registration of crying during treatment suggested more crying during acupuncture.

The authors concluded that percutaneous needle acupuncture treatments should not be recommended for infantile colic on a general basis.

The authors also provide this further comment: “Our blinding test validated IPD meta-analysis of minimal acupuncture treatments of infantile colic did not show clinically relevant effects in pain reduction as estimated by differences in crying time between needle acupuncture intervention and no acupuncture control. Analyses indicated that acupuncture treatment induced crying in many of the children. Caution should therefore be exercised in recommending potentially painful treatments with uncertain efficacy in infants. The studies are few, the analysis is made on small samples of individuals, and conclusions should be considered in this context. With this limitation in mind, our findings do not support the idea that percutaneous needle acupuncture should be recommended for treatment of infantile colic on a general basis.”

So, returning to the two questions that I listed above – what are the answers?

I think they must be:

- No.

- No.

In the comment section of a recent post, we saw a classic example of the type of reasoning that many alternative practitioners seem to like. In order to offer a service to other practitioners, I will elaborate on it here. The reasoning roughly follows these simple 10 steps:

- My treatment works.

- My treatment requires a lot of skills, training and experience.

- Most people fail to appreciate how subtle my treatment really is.

- In fact, only few practitioners manage do it the way it has to be done.

- The negative trials of my treatment are false-negative because they were conducted by incompetent practitioners.

- In any case, for a whole range of reasons, my treatment cannot be pressed into the straight jacket of a clinical trial.

- My treatment is therefore not supported by the type of evidence people who don’t understand it insist upon.

- Therefore, we have to rely on the best evidence that is available to date.

- And that clearly is the experience of therapists and patients.

- So, the best evidence unquestionably confirms that my treatment works.

The case I mentioned above was that of an acupuncturist defending his beloved acupuncture. To a degree, the argument put forward by him sounded (to fellow acupuncturists) reasonable. On closer inspection, however, they seem far less so, perhaps even fallacious. If you are an acupuncturist, you will, of course, disagree with me. Therefore, I invite all acupuncturists to imagine a homeopath arguing in that way (which they often do). Would you still find the line of arguments reasonable?

And what, if you are a homeopath? Then I invite you to imagine that a crystal therapist argues in that way (which they often do). Would you still find the line of arguments reasonable?

And what, if you are a crystal therapist? …

I am not getting anywhere, am I?

To make my point, it might perhaps be best, if I created my very own therapy!

Here we go: it’s called ENERGY PRESERVATION THERAPY (EPT).

I have discovered, after studying ancient texts from various cultures, that the vital energy of our closest deceased relatives can be transferred by consuming their carbon molecules. The most hygienic way to achieve this is to have our deceased relatives cremated and consume their ashes afterwards. The cremation, storage of the ashes, as well as their preparation and regular consumption all have to be highly individualised, of course. But I am certain that this is the only way to preserve their vital force and transfer it to a living relative. The benefits of this treatment are instantly visible.

As it happens, I run special three-year (6 years part-time) courses at the RSM in London to teach other clinicians how exactly to do this. And I should warn you: they are neither cheap nor easy; we are talking of very skilled stuff here.

What! You doubt that my treatment works?

Doubt no more!

Here are 10 convincing arguments for it:

- EPT works, I have 10 years of experience and seen hundreds of cases.

- EPT requires a lot of skills, training and experience.

- Most people fail to appreciate how subtle EPT really is.

- In fact, only few practitioners manage do EPT the way it has to be done.

- The negative trials of EPT are false-negative because they were conducted by incompetent practitioners.

- In any case, for a whole range of reasons, EPT cannot be pressed into the straight jacket of a clinical trial.

- EPT is therefore not supported by the type of evidence people who don’t understand it insist upon.

- Therefore, we have to rely on the best evidence that is available to date.

- And that clearly is the experience of therapists and patients.

- So, the best evidence unquestionably confirms that EPT works.

Convinced?

No?

You do surprise me!

Why then are you convinced of the effectiveness of acupuncture, homeopathy, etc?

“Non-reproducible single occurrences are of no significance to science”, this quote by Karl Popper often seems to get forgotten in medicine, particularly in alternative medicine. It indicates that findings have to be reproducible to be meaningful – if not, we cannot be sure that the outcome in question was caused by the treatment we applied.

This is thus a question of cause and effect.

The statistician Sir Austin Bradford Hill proposed in 1965 a set of 9 criteria to provide evidence of a relationship between a presumed cause and an observed effect while demonstrating the connection between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. One of his criteria is consistency or reproducibility: Consistent findings observed by different persons in different places with different samples strengthens the likelihood of an effect.

By mentioning ‘different persons’, Hill seems to also establish the concept of INDEPENDENT replication.

Let me try to explain this with an example from the world of SCAM.

- A homeopath feels that childhood diarrhoea could perhaps be treated with individualised homeopathic remedies. She conducts a trial, finds a positive result and concludes that the statistically significant decrease in the duration of diarrhea in the treatment group suggests that homeopathic treatment might be useful in acute childhood diarrhea. Further study of this treatment deserves consideration.

- Unsurprisingly, this study is met with disbelieve by many experts. Some go as far as doubting its validity, and several letters to the editor appear expressing criticism. The homeopath is thus motivated to run another trial to prove her point. Its results are consistent with the finding from the previous study that individualized homeopathic treatment decreases the duration of diarrhea and number of stools in children with acute childhood diarrhea.

- We now have a replication of the original finding. Yet, for a range of reasons, sceptics are far from satisfied. The homeopath thus runs a further trial and publishes a meta-analysis of all there studies. The combined analysis shows a duration of diarrhoea of 3.3 days in the homeopathy group compared with 4.1 in the placebo group (P = 0.008). She thus concludes that the results from these studies confirm that individualized homeopathic treatment decreases the duration of acute childhood diarrhea and suggest that larger sample sizes be used in future homeopathic research to ensure adequate statistical power. Homeopathy should be considered for use as an adjunct to oral rehydration for this illness.

To most homeopaths it seems that this body of evidence from three replication is sound and solid. Consequently, they frequently cite these publications as a cast-iron proof of their assumption that individualised homeopathy is effective. Sceptics, however, are still not convinced.

Why?

The studies have been replicated alright, but what is missing is an INDEPENDENT replication.

To me this word implies two things:

- The results have to be reproduced by another research group that is unconnected to the one that conducted the three previous studies.

- That group needs to be independent from any bias that might get in the way of conducting a rigorous trial.

And why do I think this latter point is important?

Simply because I know from many years of experience that a researcher, who strongly believes in homeopathy or any other subject in question, will inadvertently introduce all sorts of biases into a study, even if its design is seemingly rigorous. In the end, these flaws will not necessarily show in the published article which means that the public will be mislead. In other words, the paper will report a false-positive finding.

It is possible, even likely, that this has happened with the three trials mentioned above. The fact is that, as far as I know, there is no independent replication of these studies.

In the light of all this, Popper’s axiom as applied to medicine should perhaps be modified: findings without independent replication are of no significance. Or, to put it even more bluntly: independent replication is an essential self-cleansing process of science by which it rids itself from errors, fraud and misunderstandings.

Having yesterday been to a ‘Skeptics in the Pub’ event on MEDITATION in Cambridge (my home town since last year) I had to think about the subject quite a bit. As I have hardly covered this topic on my blog, I am today trying to briefly summarise my view on it.

The first thing that strikes me when looking at the evidence on meditation is that it is highly confusing. There seem to be:

- a lack of clear definitions,

- hundreds of studies, most of which are of poor or even very poor quality,

- lots of people with ’emotional baggage’,

- plenty of strange links to cults and religions,

- dozens of different meditation methods and regimen,

- unbelievable claims by enthusiasts,

- lots of weirdly enthusiastic followers.

What was confirmed yesterday is the fact that, once we look at the reliable medical evidence, we are bound to find that the health claims of various meditation techniques are hugely exaggerated. There is almost no strong evidence to suggest that meditation does affect any condition. The small effects that do emerge from some meta-analyses could easily be due to residual bias and confounding; it is not possible to rigorously control for placebo effects in clinical trials of meditation.

Another thing that came out clearly yesterday is the fact that meditation might not be as risk-free as it is usually presented. Several cases of psychoses after meditation are on record; some of these are both severe and log-lasting. How often do they happen? Nobody knows! Like with most alternative therapies, there is no reporting system in place that could possibly give us anything like a reliable answer.

For me, however, the biggest danger with (certain forms of) meditation is not the risk of psychosis. It is the risk of getting sucked into a cult that then takes over the victim and more or less destroys his or her personality. I have seen this several times, and it is a truly frightening phenomenon.

In our now 10-year-old book THE DESKTOP GUIDE TO COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE, we included a chapter on meditation. It concluded that “meditation appears to be safe for most people and those with sufficient motivation to practise regularly will probably find a relaxing experience. Evidence for effectiveness in any indication is week.” Even today, this is not far off the mark, I think. If I had to re-write it now, I would perhaps mention the potential for harm and also add that, as a therapy, the risk/benefit balance of meditation fails to be convincingly positive.

PS

I highly recommend ‘Skeptics in the Pub’ events to anyone who likes stimulating talks and critical thinking.

On this blog, we constantly discuss the shortcomings of clinical trials of (and other research into) alternative medicine. Yet, there can be no question that research into conventional medicine is often unreliable as well.

What might be the main reasons for this lamentable fact?

A recent BMJ article discussed 5 prominent reasons:

Firstly, much research fails to address questions that matter. For example, new drugs are tested against placebo rather than against usual treatments. Or the question may already have been answered, but the researchers haven’t undertaken a systematic review that would have told them the research was not needed. Or the research may use outcomes, perhaps surrogate measures, that are not useful.

Secondly, the methods of the studies may be inadequate. Many studies are too small, and more than half fail to deal adequately with bias. Studies are not replicated, and when people have tried to replicate studies they find that most do not have reproducible results.

Thirdly, research is not efficiently regulated and managed. Quality assurance systems fail to pick up the flaws in the research proposals. Or the bureaucracy involved in having research funded and approved may encourage researchers to conduct studies that are too small or too short term.

Fourthly, the research that is completed is not made fully accessible. Half of studies are never published at all, and there is a bias in what is published, meaning that treatments may seem to be more effective and safer than they actually are. Then not all outcome measures are reported, again with a bias towards those are positive.

Fifthly, published reports of research are often biased and unusable. In trials about a third of interventions are inadequately described meaning they cannot be implemented. Half of study outcomes are not reported.

END OF QUOTE

Apparently, these 5 issues are the reason why 85% of biomedical research is being wasted.

That is in CONVENTIONAL medicine, of course.

What about alternative medicine?

There is no question in my mind that the percentage figure must be even higher here. But do the same reasons apply? Let’s go through them again:

- Much research fails to address questions that matter. That is certainly true for alternative medicine – just think of the plethora of utterly useless surveys that are being published.

- The methods of the studies may be inadequate. Also true, as we have seen hundreds of time on this blog. Some of the most prevalent flaws include in my experience small sample sizes, lack of adequate controls (e.g. A+B vs B design) and misleading conclusions.

- Research is not efficiently regulated and managed. True, but probably not a specific feature of alternative medicine research.

- Research that is completed is not made fully accessible. most likely true but, due to lack of information and transparency, impossible to judge.

- Published reports of research are often biased and unusable. This is unquestionably a prominent feature of alternative medicine research.

All of this seems to indicate that the problems are very similar – similar but much more profound in the realm of alternative medicine, I’d say based on many years of experience (yes, what follows is opinion and not evidence because the latter is hardly available).

The thing is that, like almost any other job, research needs knowledge, skills, training, experience, integrity and impartiality to do it properly. It simply cannot be done well without such qualities. In alternative medicine, we do not have many individuals who have all or even most of these qualities. Instead, we have people who often are evangelic believers in alternative medicine, want to further their field by doing some research and therefore acquire a thin veneer of scientific expertise.

In my 25 years of experience in this area, I have not often seen researchers who knew that research is for testing hypotheses and not for trying to prove one’s hunches to be correct. In my own team, those who were the most enthusiastic about a particular therapy (and were thus seen as experts in its clinical application), were often the lousiest researchers who had the most difficulties coping with the scientific approach.

For me, this continues to be THE problem in alternative medicine research. The investigators – and some of them are now sufficiently skilled to bluff us to believe they are serious scientists – essentially start on the wrong foot. Because they never were properly trained and educated, they fail to appreciate how research proceeds. They hardly know how to properly establish a hypothesis, and – most crucially – they don’t know that, once that is done, you ought to conduct investigation after investigation to show that your hypothesis is incorrect. Only once all reasonable attempts to disprove it have failed, can your hypothesis be considered correct. These multiple attempts of disproving go entirely against the grain of an enthusiast who has plenty of emotional baggage and therefore cannot bring him/herself to honestly attempt to disprove his/her beloved hypothesis.

The plainly visible result of this situation is the fact that we have dozens of alternative medicine researchers who never publish a negative finding related to their pet therapy (some of them were admitted to what I call my HALL OF FAME on this blog, in case you want to verify this statement). And the lamentable consequence of all this is the fast-growing mountain of dangerously misleading (but often seemingly robust) articles about alternative treatments polluting Medline and other databases.

Please bear with me and have a look at the three short statements quoted below:

1 Reiki

… a Reiki practitioner channels this pure ‘chi’, the ‘ki’ in Reiki, or energy through her hands to the recipient, enhancing and stimulating the individual’s natural ability to restore a sense of wellbeing. It is instrumental in lowering stress levels, and therefore may equip the recipient with increased resources to deal with the physical as well as the emotional, mental and spiritual problems raised by his/her condition. It is completely natural and safe, and can be used alongside conventional medicine as well as other complementary therapies or self-help techniques.

It has been documented that patients receiving chemotherapy have commented on feeling less distress and discomfort when Reiki is part of their care plan. Besides feeling more energy, hope and tranquillity, some patients have felt that the side-effects of chemotherapy were easier to cope with. Reiki has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, to raise energy levels in tired and apathetic patients. It is of great value in degenerative disease for the very reasons that pain and anxiety can be reduced.

The treatment is gentle, supportive and non-invasive, the patient always remains clothed. Even though the origins of reiki are spiritual in nature, Reiki imposes no set of beliefs. It can be used by people of different cultural backgrounds and faith, or none at all. This makes it particularly suitable in medical settings. Predicting who would or would not like to receive Reiki is impossible.

2 Emmett

EMMETT is a gentle soft tissue release technique developed by Australian remedial therapist Ross Emmett. It involves the therapist using light finger pressure at specific locations on the body to elicit a relaxation response within the area of concern.

Cancer impacts people in different ways throughout the journey of diagnosis, treatment and recovery. Many have found the EMMETT Technique to be very beneficial in a number of ways. Although pressure therapy isn’t new (e.g. acupressure and trigger point therapy are already well known), the amount of pressure required with EMMETT is much lighter and the placement of the pressure is unique to EMMETT Therapy.

Many cancer patients undergo surgery and experience post-surgery tightness and tension around the surgery site in the scar tissue and further afield through the connective tissue or fascia as the body heals. They experience restricted range of movement that may be painful too. Mastectomy patients as an example will usually experience pain or tenderness, swelling around the surgery site, limited arm or shoulder movement, and even numbness in the chest or upper arm. Here’s where EMMETT can assist. With gentle pressure to specific points, many women have received relief from the pain, reduced swelling and much improved range of movement. There are multiple EMMETT points that are used to help these women and that give the therapist a range of options depending on the patient’s specific concern.

Many cancer patients also experience fatigue, increased risk of infection, nausea, appetite changes and constipation as common side effects of chemotherapy. These symptoms can also be greatly supported with a designated sequence where the EMMETT Therapist gently stimulates areas all around the body for an overall effect. Patients report reduction in swelling, feelings of lightness, increased energy, more robust emotional well-being, less pain and feeling better generally within themselves.

3 Daoyin Tao

The theory behind this massage lies in traditional Chinese medicine, so covers yin and yang, five elements and Chinese face reading from a health perspective. It enables the emotional elements behind disease to be explored. For example, the Chinese will say that grief is held in the Lung, anger in the liver, and fear in the kidney.

For this half hour massage there is no need for the patient to remove clothes, so it is a lovely way of receiving a massage where body image may be an issue, or where lines and feeds are in place, making removal of clothes difficult. This massage therapy can be given not only in a clinic, but also on the day unit, on hospital wards and even in an intensive care unit.

In working the meridian system the therapist is able to work the whole body, reaching areas other than the contact zone. Patients have commented that this deeply relaxing and soothing massage is; “one of the best massages I have ever had”. It has been proven to be beneficial with problems of; sleep, headaches, anxiety, watery eyes, shoulder and neck tension, sinusitis and panic attacks, jaw tension, fear, emotional trauma/distress.

END OF QUOTES

__________________________________________________________________________

Where do you think these statements come from?

They sound as though they come from a profoundly uncritical source, such as a commercial organisation trying to persuade customers to use some dodgy treatments, don’t they?

Wrong!

They come from the NHS! To be precise, they come from the NHS NATURAL HEALTH SCHOOL in Harrowgate, a service that offers a range of free complementary therapy treatments to patients and their relatives who are affected by a cancer diagnosis and are either receiving their cancer treatment at Harrogate or live in the Harrogate and Rural District.

This NHS school offers alternative treatments to cancer patients and claim that they know from experience, that when Complementary Therapies are integrated into patient care we are able to deliver safe, high quality care which fulfils the needs of even the most complex of patients.

In addition, they also run courses for alternative practitioners. Their reflexology course, for instance, covers all of the following:

- Explore the history and origins of Reflexology

- Explore the use of various mediums used in treatment including waxes, balms, powders and oils

- Explore the philosophy of holism and its role within western bio medicine

- Reading the feet/hands and mapping the reflex points

- Relevant anatomy, physiology and pathology

- Managing a wide range of conditions

- Legal implications

- Cautions and contraindications

- Assessment and client care

- Practical reflexology skills and routines

- Treatment planning

I imagine that the initiators of the school are full of the very best, altruistic intentions. I therefore have considerable difficulties in criticising them. Yet, I do strongly feel that the NHS should be based on good evidence; and that much of the school’s offerings seems to be the exact opposite. In fact, the NHS-label is being abused for giving undeserved credibility to outright quackery, in my view.

I am sure the people behind this initiative only want to help desperate patients. I also suspect that most patients are very appreciative of their service. But let me put it bluntly: we do not need to make patients believe in mystical life forces, meridians and magical energies; if nothing else, this undermines rational thought (and we could do with a bit more of that at present). There are plenty of evidence-based approaches which, when applied with compassion and empathy, will improve the well-being of these patients without all the nonsense and quackery in which the NHS NATURAL HEALTH SCHOOL seems to specialise.

It is bad enough, I believe, that such nonsense is currently popular and increasingly politically correct, but let’s keep/make the NHS evidence-based, please!

An article entitled “Homeopathy in the Age of Antimicrobial Resistance: Is It a Viable Treatment for Upper Respiratory Tract Infections?” cannot possibly be ignored on this blog, particularly if published in the amazing journal ‘Homeopathy‘. The title does not bode well, in my view – but let’s see. Below, I copy the abstract of the paper without any changes; all I have done is include a few numbers in brackets; they refer to my comments that follow.

START OF ABSTRACT

Acute upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and their complications are the most frequent cause of antibiotic prescribing in primary care. With multi-resistant organisms proliferating, appropriate alternative treatments to these conditions are urgently required. Homeopathy presents one solution (1); however, there are many methods of homeopathic prescribing. This review of the literature considers firstly whether homeopathy offers a viable alternative therapeutic solution for acute URTIs (2) and their complications, and secondly how such homeopathic intervention might take place.

METHOD:

Critical review of post 1994 (3) clinical studies featuring homeopathic treatment of acute URTIs and their complications. Study design, treatment intervention, cohort group, measurement and outcome were considered. Discussion focused on the extent to which homeopathy is used to treat URTIs, rate of improvement and tolerability of the treatment, complications of URTIs, prophylactic and long-term effects, and the use of combination versus single homeopathic remedies.

RESULTS:

Multiple peer-reviewed (4) studies were found in which homeopathy had been used to treat URTIs and associated symptoms (cough, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, otitis media, acute sinusitis, etc.). Nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 8 observational/cohort studies were analysed, 7 of which were paediatric studies. Seven RCTs used combination remedies with multiple constituents. Results for homeopathy treatment were positive overall (5), with faster resolution, reduced use of antibiotics and possible prophylactic and longer-term benefits.

CONCLUSIONS:

Variations in size, location, cohort and outcome measures make comparisons and generalisations concerning homeopathic clinical trials for URTIs problematic (6). Nevertheless, study findings suggest at least equivalence between homeopathy and conventional treatment for uncomplicated URTI cases (7), with fewer adverse events and potentially broader therapeutic outcomes. The use of non-individualised homeopathic compounds tailored for the paediatric population merits further investigation, including through cohort studies (8). In the light of antimicrobial resistance, homeopathy offers alternative strategies for minor infections and possible prevention of recurring URTIs (9).

END OF ABSTRACT

And here are my comments:

- This sounds as though the author already knew the conclusion of her review before she even started.

- Did she not just state that homeopathy is a solution?

- This is most unusual; why were pre-1994 articles not considered?

- This too is unusual; that a study is peer-reviewed is not really possible to affirm, one must take the journal’s word for it. Yet we know that peer-review is farcical in the realm of alternative medicine (see also below). Therefore, this is an odd inclusion criterion to mention in an abstract.

- An overall positive result obtained by including uncontrolled observational and cohort studies lacking a control group is meaningless. There is also no assessment of the quality of the RCTs; after a quick glance, I get the impression that the methodologically sound studies do not show homeopathy to be superior to placebo.

- Reviewers need to disentangle these complicating factors and arrive at a conclusion. This is almost invariably problematic, but it is the reviewer’s job.

- What might be the conventional treatment of uncomplicated URTI?

- Why on earth cohort studies? They tell us nothing about equivalence, efficacy etc.

- To reach that conclusion seems to have been the aim of this review (see my point number 1). If I am not mistaken, antibiotics are not indicated in the vast majority of cases of uncomplicated URTI. This means that the true alternative in the light of antimicrobial resistance is to not prescribe antibiotics and treat the patient symptomatically. No need at all for homeopathic placebos, and no need for wishful thinking reviews!

In the paper, the author explains her liking of uncontrolled studies: Non-RCTs and patient reported surveys are considered by some to be inferior forms of research evidence, but are important adjuncts to RCTs that can measure key markers such as patient satisfaction, quality of life and functional health. Observational studies such as clinical outcome studies and case reports, monitoring the effects of homeopathy in real-life clinical settings, are a helpful adjunct to RCTs and more closely reflect real-life experiences of patients and physicians than RCTs, and are therefore considered in this study. I would counter that this is not an issue of inferiority but one that depends on the research question; if the research question relates to efficacy/effectiveness, uncontrolled data are next to useless.

She also makes fairly categorical statements in the conclusion section of the paper about the effectiveness of homeopathy: [the] combined evidence from these and other studies suggests that homeopathic treatment can exert biological effects with fewer adverse events and broader therapeutic opportunities than conventional medicine in the treatment of URTIs. Given the cost implications of treating URTIs and their complications in children, and the relative absence of effective alternatives without potential side effects, the use of non-individualised homeopathic compounds tailored for the paediatric population merits further investigation, including through large-scale cohort studies… the most important evidence still arises from practical clinical experience and from the successful treatment of millions of patients. I would counter that none of these conclusions are warranted by the data presented.

From reading the paper, I get the impression that the author (the paper provides no information about her conflicts of interest, nor funding source) is a novice to conducting reviews (even though the author is a senior lecturer, the paper reads more like a poorly organised essay than a scientific review). I am therefore hesitant to criticise her – but I do nevertheless find the fact deplorable that her article passed the peer-review process of ‘Homeopathy‘ and was published in a seemingly respectable journal. If anything, articles of this nature are counter-productive for everyone concerned; they certainly do not further effective patient care, and they give homeopathy-research a worse name than it already has.

@Rich It sounds to me as if you are at least partly open-minded, and take a more genuinely scientific approach than most here – i.e. rather than dismissing something with a lot of intriguing evidence behind it (even if much of this evidence is still hotly debated) mainly on the grounds that it ‘sounds a bit silly’, you understand that it’s possible to look at something like acupuncture objectively without being put off by the strange terminology associated with it. I strongly urge you to consult various other outlets as well as this one before coming to any final judgement. http://www.evidencebasedacupuncture.org/ for example is run by intelligent people genuinely trying to present the facts as they see them. Yes, they have an ‘agenda’ in that they are acupuncturists, but I can assure you, having had detailed discussions with some of them, that they are motivated by the urge to see acupuncture help more people rather than anything sinister, and they are trying to present an honest appraisal of the evidence. No doubt virtually everyone here will dismiss everything there with (or without) a cursory glance, but perhaps you won’t fall into that category. I hope you find something of interest there, and come to a balanced opinion.