clinical trial

In previous posts, I have been scathing about chiropractors (DCs) treating children; for instance here:

- Despite calling themselves ‘doctors’, they are nothing of the sort.

- DCs are not adequately educated or trained to treat children.

- They nevertheless often do so, presumably because this constitutes a significant part of their income.

- Even if they felt confident to be adequately trained, we need to remember that their therapeutic repertoire is wholly useless for treating sick children effectively and responsibly.

- Therefore, harm to children is almost inevitable.

- To this, we must add the risk of incompetent advice from DCs – just think of immunisations.

Now we have more data on this subject. This new study investigated the effectiveness of adding manipulative therapy to other conservative care for spinal pain in a school-based cohort of Danish children aged 9–15 years.

The design was a two-arm pragmatic randomised controlled trial, nested in a longitudinal open cohort study in Danish public schools. 238 children from 13 public schools were included. A text message system and clinical examinations were used for data collection. Interventions included either (1) advice, exercises and soft-tissue treatment or (2) advice, exercises and soft-tissue treatment plus manipulative therapy. The primary outcome was number of recurrences of spinal pain. Secondary outcomes were duration of spinal pain, change in pain intensity and Global Perceived Effect.

No significant difference was found between groups in the primary outcomes of the control group and intervention group. Children in the group receiving manipulative therapy reported a higher Global Perceived Effect. No adverse events were reported.

The authors – well-known proponents of chiropractic (who declared no conflicts of interest) – concluded that adding manipulative therapy to other conservative care in school children with spinal pain did not result in fewer recurrent episodes. The choice of treatment—if any—for spinal pain in children therefore relies on personal preferences, and could include conservative care with and without manipulative therapy. Participants in this trial may differ from a normal care-seeking population.

The study seems fine, but what a conclusion!!!

After demonstrating that chiropractic manipulation is useless, the authors state that the treatment of kids with back pain could include conservative care with and without manipulative therapy. This is more than a little odd, in my view, and seems to suggest that chiropractors live on a different planet from those of us who can think rationally.

Psoriasis is one of those conditions that is

- chronic,

- not curable,

- irritating to the point where it reduces quality of life.

In other words, it is a disease for which virtually all alternative treatments on the planet are claimed to be effective. But which therapies do demonstrably alleviate the symptoms?

This review (published in JAMA Dermatology) compiled the evidence on the efficacy of the most studied complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities for treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis and discusses those therapies with the most robust available evidence.

PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov searches (1950-2017) were used to identify all documented CAM psoriasis interventions in the literature. The criteria were further refined to focus on those treatments identified in the first step that had the highest level of evidence for plaque psoriasis with more than one randomized clinical trial (RCT) supporting their use. This excluded therapies lacking RCT data or showing consistent inefficacy.

A total of 457 articles were found, of which 107 articles were retrieved for closer examination. Of those articles, 54 were excluded because the CAM therapy did not have more than 1 RCT on the subject or showed consistent lack of efficacy. An additional 7 articles were found using references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 44 RCTs (17 double-blind, 13 single-blind, and 14 nonblind), 10 uncontrolled trials, 2 open-label nonrandomized controlled trials, 1 prospective controlled trial, and 3 meta-analyses.

Compared with placebo, application of topical indigo naturalis, studied in 5 RCTs with 215 participants, showed significant improvements in the treatment of psoriasis. Treatment with curcumin, examined in 3 RCTs (with a total of 118 participants), 1 nonrandomized controlled study, and 1 uncontrolled study, conferred statistically and clinically significant improvements in psoriasis plaques. Fish oil treatment was evaluated in 20 studies (12 RCTs, 1 open-label nonrandomized controlled trial, and 7 uncontrolled studies); most of the RCTs showed no significant improvement in psoriasis, whereas most of the uncontrolled studies showed benefit when fish oil was used daily. Meditation and guided imagery therapies were studied in 3 single-blind RCTs (with a total of 112 patients) and showed modest efficacy in treatment of psoriasis. One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs examined the association of acupuncture with improvement in psoriasis and showed significant improvement with acupuncture compared with placebo.

The authors concluded that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis are indigo naturalis, curcumin, dietary modification, fish oil, meditation, and acupuncture. This review will aid practitioners in advising patients seeking unconventional approaches for treatment of psoriasis.

I am sorry to say so, but this review smells fishy! And not just because of the fish oil. But the fish oil data are a good case in point: the authors found 12 RCTs of fish oil. These details are provided by the review authors in relation to oral fish oil trials: Two double-blind RCTs (one of which evaluated EPA, 1.8g, and DHA, 1.2g, consumed daily for 12 weeks, and the other evaluated EPA, 3.6g, and DHA, 2.4g, consumed daily for 15 weeks) found evidence supporting the use of oral fish oil. One open-label RCT and 1 open-label non-randomized controlled trial also showed statistically significant benefit. Seven other RCTs found lack of efficacy for daily EPA (216mgto5.4g)or DHA (132mgto3.6g) treatment. The remainder of the data supporting efficacy of oral fish oil treatment were based on uncontrolled trials, of which 6 of the 7 studies found significant benefit of oral fish oil. This seems to support their conclusion. However, the authors also state that fish oil was not shown to be effective at several examined doses and duration. Confused? Yes, me too!

Even more confusing is their failure to mention a single trial of Mahonia aquifolium. A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology included 5 RCTs of Mahonia aquifolium which, according to these authors, provided ‘limited support’ for its effectiveness. How could they miss that?

More importantly, how could the reviewers miss to conduct a proper evaluation of the quality of the studies they included in their review (even in their abstract, they twice speak of ‘robust evidence’ – but how can they without assessing its robustness? [quantity is not remotely the same as quality!!!]). Without a transparent evaluation of the rigour of the primary studies, any review is nearly worthless.

Take the 12 acupuncture trials, for instance, which the review authors included based not on an assessment of the studies but on a dodgy review published in a dodgy journal. Had they critically assessed the quality of the primary studies, they could have not stated that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis …[include]… acupuncture. Instead they would have had to admit that these studies are too dubious for any firm conclusion. Had they even bothered to read them, they would have found that many are in Chinese (which would have meant they had to be excluded in their review [as many pseudo-systematic reviewers, the authors only considered English papers]).

There might be a lesson in all this – well, actually I can think of at least two:

- Systematic reviews might well be the ‘Rolls Royce’ of clinical evidence. But even a Rolls Royce needs to be assembled correctly, otherwise it is just a heap of useless material.

- Even top journals do occasionally publish poor-quality and thus misleading reviews.

Yesterday, I was interviewed and filmed by a Canadian TV-journalist. Even though the subject was osteopathy (apparently, in Canada, osteopathy is strong and full of woo), we found ourselves talking about ‘oil pulling’. I knew next to nothing about this alternative therapy, but learnt that it was big in North America. When the TV-crew had left my home, I therefore read up about it. I must admit, I was more than a little sceptical about the therapy – not least because I soon found articles by fellow sceptics that were less than complimentary – but, as I studied the original research on oil pulling, my scepticism somewhat waned.

So, what is oil pulling? It is the use of oil for swishing it around your mouth for alleged health benefits. Here are several short points that might explain it more fully:

- Oil pulling is said to have roots that reach back to ancient Hindu texts. Coconut or sesame oils are usually employed for this therapy.

- The mechanism of action (if there is one at all) is poorly understood, and several theories have been put forward:

Alkali hydrolysis of fat results in saponification or “soap making” process. Since the oils used for oil pulling contain fat, the alkali hydrolysis process emulsifies the fat into bicarbonate ions, normally found in the saliva. Soaps then blend in the oil, increase the surface area of the oil, and thus cleanse the teeth and gums.

A second theory suggests that the viscous nature of the oil inhibits plaque accumulation and adhesion of bacteria.

A third theory holds that the antioxidants present in the oil prevent lipid peroxidation, resulting in an antibiotic-like effect helping in the destruction of microorganisms.

- Oil pulling is recommended to be carried out in the morning on an empty stomach. About 10 ml of oil is swished between the teeth for a duration of approximately 15-20 min and spat out. This ritual should be followed by rinsing and tooth brushing. The practice should be repeated regularly, even three times daily for acute diseases.

- To my surprise, oil pulling has been tested in clinical trials. Some of these investigations seem reasonably sound and suggest that coconut oil pulling reduces potentially harmful bacteria in the mouth.[1] This effect has been shown to lead to a reduction in dental plaque formation[2] , halitosis (bad breath) [3] and gingivitis. [4]

- The evidence for these oral effects is by no means strong, but I have not found studies that show negative results.

- Dentists – even the bizarre species of ‘holistic dentists‘ – do not seem to be balled over by oil pulling (some malicious minds might speculate that this is so because they cannot earn much money with it).

- The claimed benefits of oil pulling are, however, not limited to the oral cavity. It is advocated also for the prevention and treatment of conditions such as headaches, migraines, thrombosis, eczema, diabetes and asthma.[5] Some proponents also claim that oil pulling is a detox therapy. Unsurprisingly, none of these claims are supported by good evidence.

- As long as you don’t swallow the oil, there are no serious risks associated with oil pulling.

So, what is the conclusion? To me, the evidence looks promising as far as oral health is concerned. For all other indication, oil pulling is neither plausible nor evidence-based.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27891311

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18408265

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21911944

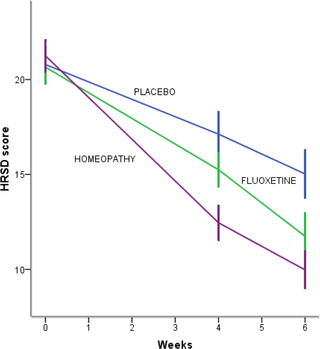

This systematic review included 18 studies assessing homeopathy in depression. Two double-blind placebo-controlled trials of homeopathic medicinal products (HMPs) for depression were assessed. The first trial (N = 91) with high risk of bias found HMPs were non-inferior to fluoxetine at 4 (p = 0.654) and 8 weeks (p = 0.965); whereas the second trial (N = 133), with low risk of bias, found HMPs was comparable to fluoxetine (p = 0.082) and superior to placebo (p < 0.005) at 6 weeks.

The remaining research had unclear/high risk of bias. A non-placebo-controlled RCT found standardised treatment by homeopaths comparable to fluvoxamine; a cohort study of patients receiving treatment provided by GPs practising homeopathy reported significantly lower consumption of psychotropic drugs and improved depression; and patient-reported outcomes showed at least moderate improvement in 10 of 12 uncontrolled studies. Fourteen trials provided safety data. All adverse events were mild or moderate, and transient. No evidence suggested treatment was unsafe.

The authors concluded that limited evidence from two placebo-controlled double-blinded trials suggests HMPs might be comparable to antidepressants and superior to placebo in depression, and patients treated by homeopaths report improvement in depression. Overall, the evidence gives a potentially promising risk benefit ratio. There is a need for additional high quality studies.

It is worth having a look at these two studies, I think.

The 1st (2011) study is from Brazil

Here is its abstract:

Homeopathy is a complementary and integrative medicine used in depression, The aim of this study is to investigate the non-inferiority and tolerability of individualized homeopathic medicines [Quinquagintamillesmial (Q-potencies)] in acute depression, using fluoxetine as active control. Ninety-one outpatients with moderate to severe depression were assigned to receive an individualized homeopathic medicine or fluoxetine 20 mg day−1 (up to 40 mg day−1) in a prospective, randomized, double-blind double-dummy 8-week, single-center trial. Primary efficacy measure was the analysis of the mean change in the Montgomery & Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) depression scores, using a non-inferiority test with margin of 1.45. Secondary efficacy outcomes were response and remission rates. Tolerability was assessed with the side effect rating scale of the Scandinavian Society of Psychopharmacology. Mean MADRS scores differences were not significant at the 4th (P = .654) and 8th weeks (P = .965) of treatment. Non-inferiority of homeopathy was indicated because the upper limit of the confidence interval (CI) for mean difference in MADRS change was less than the non-inferiority margin: mean differences (homeopathy-fluoxetine) were −3.04 (95% CI −6.95, 0.86) and −2.4 (95% CI −6.05, 0.77) at 4th and 8th week, respectively. There were no significant differences between the percentages of response or remission rates in both groups. Tolerability: there were no significant differences between the side effects rates, although a higher percentage of patients treated with fluoxetine reported troublesome side effects and there was a trend toward greater treatment interruption for adverse effects in the fluoxetine group. This study illustrates the feasibility of randomized controlled double-blind trials of homeopathy in depression and indicates the non-inferiority of individualized homeopathic Q-potencies as compared to fluoxetine in acute treatment of outpatients with moderate to severe depression.

There are many important points to make about this trial:

- Contrary to what the reviewers claim, the trial had no placebo group.

- It was a double-dummy equivalence study comparing individualised homeopathy with the antidepressant fluoxetine.

- Fluoxetine might have been under-dosed (see below).

- Equivalence studies require large sample sizes, and with just 91 patients (only 55 of whom finished the study), this trial was underpowered which means the finding of equivalence is false positive.

- The authors noted that a higher percentage of troublesome adverse effects reported by patients receiving fluoxetine. This means that the trial was not double-blind; patients were able to tell by their side-effects which group they were in.

- The authors also state that more patients randomized to homeopathy than to fluoxetine were excluded due to worsening of their depressive symptoms. I think this confirms that homeopathy was ineffective.

The 2nd (2015) study is from Mexico

Here is its abstract:

Background: Perimenopausal period refers to the interval when women’s menstrual cycles become irregular and is characterized by an increased risk of depression. Use of homeopathy to treat depression is widespread but there is a lack of clinical trials about its efficacy in depression in peri- and postmenopausal women. The aim of this study was to assess efficacy and safety of individualized homeopathic treatment versus placebo and fluoxetine versus placebo in peri- and postmenopausal women with moderate to severe depression.

Methods/Design: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double-dummy, superiority, three-arm trial with a 6 week follow-up study was conducted. The study was performed in a public research hospital in Mexico City in the outpatient service of homeopathy. One hundred thirty-three peri- and postmenopausal women diagnosed with major depression according to DSM-IV (moderate to severe intensity) were included. The outcomes were: change in the mean total score among groups on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Beck Depression Inventory and Greene Scale, after 6 weeks of treatment, response and remission rates, and safety. Efficacy data were analyzed in the intention-to-treat population (ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test).

Results: After a 6-week treatment, homeopathic group was more effective than placebo by 5 points in Hamilton Scale. Response rate was 54.5% and remission rate, 15.9%. There was a significant difference among groups in response rate definition only, but not in remission rate. Fluoxetine-placebo difference was 3.2 points. No differences were observed among groups in the Beck Depression Inventory. Homeopathic group was superior to placebo in Greene Climacteric Scale (8.6 points). Fluoxetine was not different from placebo in Greene Climacteric Scale.

Conclusion: Homeopathy and fluoxetine are effective and safe antidepressants for climacteric women. Homeopathy and fluoxetine were significantly different from placebo in response definition only. Homeopathy, but not fluoxetine, improves menopausal symptoms scored by Greene Climacteric Scale.

And here are my critical remarks about this trial:

- The aim of a small study like this cannot be to assess or draw conclusions about the safety of the interventions used; for this purpose, we need sample sizes that are at least one dimension bigger.

- Fluoxetine might have been under-dosed (see below).

- The blinding of patients might have been jeopardized by patients experiencing the specific side-effects of fluoxetine. The authors reported adverse effects in all three groups. However, the characteristic and most common side-effects of fluoxetine (such as hives, itching, skin rash, restlessness, inability to sit still) were not included.

________________________________________________

Usual Adult Dose for Depression

Immediate-release oral formulations:

Initial dose: 20 mg orally once a day in the morning, increased after several weeks if sufficient clinical improvement is not observed

Maintenance dose: 20 to 60 mg orally per day

Maximum dose: 80 mg orally per day

Delayed release oral capsules:

Initial dose: 90 mg orally once a week, commenced 7 days after the last daily dose of immediate-release fluoxetine 20 mg formulations.

_________________________________________________

Considering all this, I feel that the conclusions of the above review are far too optimistic and not justified. In fact, I find them misleading, dangerous, unethical and depressing.

Bacterial vaginosis is a common condition which is more than a triviality. It can have serious consequences including pelvic inflammatory disease, endometritis, postoperative vaginal cuff infections, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and chorioamnionitis. Therefore, it is important to treat it adequately with antibiotics. But are there other options as well?

There are plenty of alternative or ‘natural’ treatments on offer. But do they work?

This trial was conducted on 127 women with bacterial vaginosis to compare a vaginal suppository of metronidazole with Forzejeh, a vaginal suppository of herbal Persian medicine combination of

- Tribulus terrestris,

- Myrtus commuis,

- Foeniculum vulgare,

- Tamarindus indica.

The patients (63 in metronidazole group and 64 in Forzejeh group) received the medications for 1 week. Their symptoms including the amount and odour of discharge and cervical pain were assessed using a questionnaire. Cervical inflammation and Amsel criteria (pH of vaginal discharge, whiff test, presence of clue cells and Gram staining) were investigated at the beginning of the study and 14 days after treatment.

The amount and odour of discharge, Amsel criteria, pelvic pain and cervical inflammation significantly decreased in Forzejeh and metronidazole groups (p = <.001). There was no statistically significant difference between the metronidazole and Fozejeh groups with respect to any of the clinical symptoms or the laboratory assessments.

The authors concluded that Forzejeh … has a therapeutic effect the same as metronidazole in bacterial vaginosis.

The plants in Fozejeh are assumed to have antimicrobial activities. Forzejeh has been used in folk medicine for many years but was only recently standardised. According to the authors, this study shows that the therapeutic effects of Forzejeh on bacterial vaginosis is similar to metronidazole.

Yet, I am far less convinced than these Iranian researchers. As this trial compared two active treatments, it was an equivalence study. As such, it requires a different statistical approach and a much larger sample size. The absence of a difference between the two groups is most likely due to the fact that the study was too small to show it.

If I am correct, the present investigation only demonstrates yet again that, with flawed study-designs, it is easy to produce false-positive results.

In one of his many comments, our friend Iqbal just linked to an article that unquestionably is interesting. Here is its abstract (the link also provides the full paper):

Objective: The objective was to assess the usefulness of homoeopathic genus epidemicus (Bryonia alba 30C) for the prevention of chikungunya during its epidemic outbreak in the state of Kerala, India.

Materials and Methods: A cluster- randomised, double- blind, placebo -controlled trial was conducted in Kerala for prevention of chikungunya during the epidemic outbreak in August-September 2007 in three panchayats of two districts. Bryonia alba 30C/placebo was randomly administered to 167 clusters (Bryonia alba 30C = 84 clusters; placebo = 83 clusters) out of which data of 158 clusters was analyzed (Bryonia alba 30C = 82 clusters; placebo = 76 clusters) . Healthy participants (absence of fever and arthralgia) were eligible for the study (Bryonia alba 30 C n = 19750; placebo n = 18479). Weekly follow-up was done for 35 days. Infection rate in the study groups was analysed and compared by use of cluster analysis.

Results: The findings showed that 2525 out of 19750 persons of Bryonia alba 30 C group suffered from chikungunya, compared to 2919 out of 18479 in placebo group. Cluster analysis showed significant difference between the two groups [rate ratio = 0.76 (95% CI 0.14 – 5.57), P value = 0.03]. The result reflects a 19.76% relative risk reduction by Bryonia alba 30C as compared to placebo.

Conclusion: Bryonia alba 30C as genus epidemicus was better than placebo in decreasing the incidence of chikungunya in Kerala. The efficacy of genus epidemicus needs to be replicated in different epidemic settings.

________________________________________________________________________________

I have often said the notion that homeopathy might prevent epidemics is purely based on observational data. Here I stand corrected. This is an RCT! What is more, it suggests that homeopathy might be effective. As this is an important claim, let me quickly post just 10 comments on this study. I will try to make this short (I only looked at it briefly), hoping that others complete my criticism where I missed important issues:

- The paper was published in THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN HOMEOPATHY. This is not a publication that could be called a top journal. If this study really shows something as revolutionarily new as its conclusions imply, one must wonder why it was published in an obscure and inaccessible journal.

- Several of its authors are homeopaths who unquestionably have an axe to grind, yet they do not declare any conflicts of interest.

- The abstract states that the trial was aimed at assessing the usefulness of Bryonia C30, while the paper itself states that it assessed its efficacy. The two are not the same, I think.

- The trial was conducted in 2007 and published only 7 years later; why the delay?

- The criteria for the main outcome measure were less than clear and had plenty of room for interpretation (“Any participant who suffered from fever and arthralgia (characteristic symptoms of chikungunya) during the follow-up period was considered as a case of chikungunya”).

- I fail to follow the logic of the sample size calculation provided by the authors and therefore believe that the trial was woefully underpowered.

- As a cluster RCT, its unit of assessment is the cluster. Yet the significant results seem to have been obtained by using single patients as the unit of assessment (“At the end of follow-ups it was observed that 12.78% (2525 out of 19750) healthy individuals, administered with Bryonia alba 30 C, were presented diagnosed as probable case of chikungunya, whereas it was 15.79% (2919 out of 18749) in the placebo group”).

- The p-value was set at 0.05. As we have often explained, this is far too low considering that the verum was a C30 dilution with zero prior probability.

- Nine clusters were not included in the analysis because of ‘non-compliance’. I doubt whether this was the correct way of dealing with this issue and think that an intention to treat analysis would have been better.

- This RCT was published 4 years ago. If true, its findings are nothing short of a sensation. Therefore, one would have expected that, by now, we would see several independent replications. The fact that this is not the case might mean that such RCTs were done but failed to confirm the findings above.

As I said, I would welcome others to have a look and tell us what they think about this potentially important study.

Music therapy is the use of music for therapeutic purposes. Several forms of music therapy exist. They can consist of a patient listening to live or recorded music, or of patients participating in performing music. Music therapy is usually employed to complement other treatments; it is never a curative or causal approach and mostly aimed at inducing relaxation and enhancing physical and emotional well-being, or at promoting motor and communication skills.

There is a paucity of rigorous studies assessing the effectiveness of music therapy for specific condition, not least due to methodological obstacles and funding issues. Several systematic reviews of clinical studies have nevertheless emerged and results are generally encouraging. As for hypertension, the evidence is contradictory whether passive listening to music works. One review concluded that Music may improve systolic blood pressure and should be considered as a component of care of hypertensive patients. And another review revealed a trend towards a decrease in blood pressure in hypertensive patients who received music interventions, but failed to establish a cause-effect relationship between music interventions and blood pressure reduction.

A new study might bring more clarity:

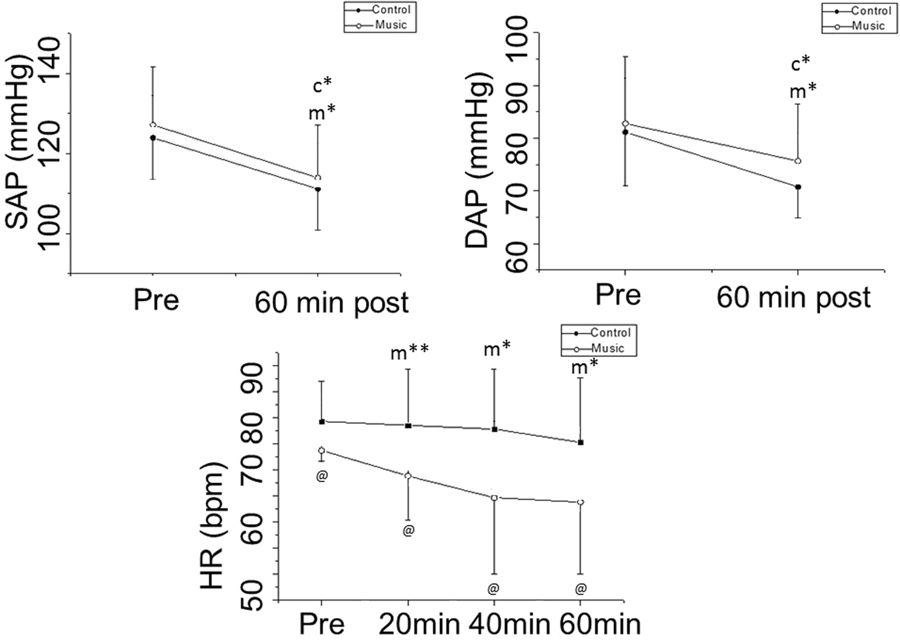

Its authors evaluated the effect of musical auditory stimulus associated with anti-hypertensive medication on heart rate (HR) autonomic control in hypertensive subjects. They included in this trial 37 well-controlled hypertensive patients designated for anti-hypertensive medication. Heart rate variability (HRV) was calculated from the HR monitor recordings of two different, randomly sorted protocols (control and music) on two separate days. Patients were examined in a resting condition 10 minutes before medication and 20 minutes, 40 minutes and 60 minutes after oral anti-hypertensive medications. Music was played throughout the 60 minutes after medication with the same intensity for all subjects in the music protocol.

The results showed analogous response of systolic and diastolic arterial pressure in both protocols. HR decreased 60 minutes after medication in the music protocol, while it remained unchanged in the control protocol. The effects of anti-hypertensive medication on SDNN (Standard deviation of all normal RR intervals), LF (low frequency, nu), HF (high frequency, nu) and alpha-1 scale were more intense in the music protocol. Blood pressure readings showed no significant differences between the two groups.

The authors concluded that musical auditory stimulus increased HR autonomic responses to anti-hypertensive medication in well-controlled hypertensive subjects.

So, there were some acute effects on HRV. But what is the clinical relevance of this effect? I am not sure, and the authors tell us little about this.

Crucially, there was no effect on blood pressure. But the study design might have been ill-suited for detecting one. I think that a much simpler trial with two parallel groups of untreated hypertensives would have been more efficient for this purpose.

As a music-lover, I would like to believe that music can be used therapeutically. Yet, for hypertensives, I find it difficult to see how this could work. Even if passive listening to music had an anti-hypertensive effect, could it be employed in clinical routine? I somehow doubt it; we can hear music for a while, but our daily activities would largely prohibit doing it for prolonged periods (and most likely it would become a nuisance after a while and would put our pressure up rather than down – think of the background music that bothers us in some shops, for instance). And how would it work when we sleep, a time during which blood pressure control can be vital?

As a music-lover, I would also argue that listening to music can be pleasantly relaxing – presumably, the anti-hypertensive effect observed in some trials relies on this effect. But surely, it can also have the opposite effect. If I strongly dislike a piece of music, I might increase my blood pressure. If a piece moves me deeply, it could easily do the same. It is probably only a certain type of music that induces relaxation; and, to make it even more complex, this type might differ from person to person.

So, is music therapy potentially a usable anti-hypertensive?

Somehow, I don’t think so!

Kinesiology tape KT is fashionable, it seems. Gullible consumers proudly wear it as decorative ornaments to attract attention and show how very cool they are.

Am I too cynical?

Perhaps.

But does KT really do anything more?

A new trial might tell us.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether adding kinesiology tape (KT) to spinal manipulation (SM) can provide any extra effect in athletes with chronic non-specific low back pain (CNLBP).

Forty-two athletes (21males, 21females) with CNLBP were randomized into two groups of SM (n = 21) and SM plus KT (n = 21). Pain intensity, functional disability level and trunk flexor-extensor muscles endurance were assessed by Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Oswestry pain and disability index (ODI), McQuade test, and unsupported trunk holding test, respectively. The tests were done before and immediately, one day, one week, and one month after the interventions and compared between the two groups.

After treatments, pain intensity and disability level decreased and endurance of trunk flexor-extensor muscles increased significantly in both groups. Repeated measures analysis, however, showed that there was no significant difference between the groups in any of the evaluations.

The authors, physiotherapists from Iran, concluded that the findings of the present study showed that adding KT to SM does not appear to have a significant extra effect on pain, disability and muscle endurance in athletes with CNLBP. However, more studies are needed to examine the therapeutic effects of KT in treating these patients.

Regular readers of my blog will be able to predict what I have to say about this study design: A+B versus B is not a meaningful test of anything. I used to claim that it cannot possibly produce a negative result – and yet, here it seems to have done exactly that!

How come?

The way I see it, there are two possibilities to explain this:

- the KT has a mildly negative effect on CNLBP; thus the expected positive placebo-effect was neutralised to result in a null-effect overall;

- the study was under-powered such that the true inter-group difference could not manifest itself.

I think the second possibility is more likely, but it does really not matter at all. Because the only lesson we can learn from this trial is this: inadequate study designs will hardly ever generate anything worthwhile.

And this is, I think, a lesson that would be valuable for many researchers.

_______________________________________________________________________

Reference

Comparing spinal manipulation with and without Kinesio Taping® in the treatment of chronic low back pain.

I am sure we have all seen these colourful tapes that nowadays decorate the bodies of many of our sporting heroes. The tape is supposed to be good for athletic performance – but not just that, it is also promoted for all sorts of health conditions, for instance, low back pain.

I am sure we have all seen these colourful tapes that nowadays decorate the bodies of many of our sporting heroes. The tape is supposed to be good for athletic performance – but not just that, it is also promoted for all sorts of health conditions, for instance, low back pain.

But is it worth the considerable investment?

This systematic review investigated the effectiveness of ‘Kinesiology Tape’ (KT) for patients with non-specific low back pain.

The researchers included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in adults with chronic non-specific low back pain that compared KT to no intervention or placebo as well as RCTs that compared KT combined with exercise against exercise alone. The methodological quality and statistical reporting of the eligible trials were measured by the 11-item PEDro scale. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE classification. Pain intensity and disability were the primary outcomes. Whenever possible, the data were pooled through meta-analysis.

Eleven RCTs were included in this systematic review. Two clinical trials compared KT to no intervention at the short-term follow-up. Four studies compared KT to placebo at short-term follow-up and two trials compared KT to placebo at intermediate-term follow-up. Five trials compared KT combined with exercises or electrotherapy to exercises or spinal manipulation alone. No statistically significant difference was found for most comparisons.

Eleven RCTs were included in this systematic review. Two clinical trials compared KT to no intervention at the short-term follow-up. Four studies compared KT to placebo at short-term follow-up and two trials compared KT to placebo at intermediate-term follow-up. Five trials compared KT combined with exercises or electrotherapy to exercises or spinal manipulation alone. No statistically significant difference was found for most comparisons.

The authors concluded that very low to moderate quality evidence shows that KT was no better than any other intervention for most the outcomes assessed in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain. We found no evidence to support the use of KT in clinical practice for patients with chronic non-specific low back pain.

So, is KT worth the often considerable investment for patients with back trouble?

Or is the current popularity of KT more of a triumph of clever marketing over scientific evidence?

I let you answer this one.

Can I tempt you to run a little (hopefully instructive) thought-experiment with you? It is quite simple: I will tell you about the design of a clinical trial, and you will tell me what the likely outcome of this study would be.

Are you game?

Here we go:

_____________________________________________________________________________

Imagine we conduct a trial of acupuncture for persistent pain (any type of pain really). We want to find out whether acupuncture is more than a placebo when it comes to pain-control. Of course, we want our trial to look as rigorous as possible. So, we design it as a randomised, sham-controlled, partially-blinded study. To be really ‘cutting edge’, our study will not have two but three parallel groups:

1. Standard needle acupuncture administered according to a protocol recommended by a team of expert acupuncturists.

2. Minimally invasive sham-acupuncture employing shallow needle insertion using short needles at non-acupuncture points. Patients in groups 1 and 2 are blinded, i. e. they are not supposed to know whether they receive the sham or real acupuncture.

3. No treatment at all.

We apply the treatments for a sufficiently long time, say 12 weeks. Before we start, after 6 and 12 weeks, we measure our patients’ pain with a validated method. We use sound statistical methods to compare the outcomes between the three groups.

WHAT DO YOU THINK THE RESULT WOULD BE?

You are not sure?

Well, let me give you some hints:

Group 3 is not going to do very well; not only do they receive no therapy at all, but they are also disappointed to have ended up in this group as they joined the study in the hope to get acupuncture. Therefore, they will (claim to) feel a lot of pain.

Group 2 will be pleased to receive some treatment. However, during the course of the 6 weeks, they will get more and more suspicious. As they were told during the process of obtaining informed consent that the trial entails treating some patients with a sham/placebo, they are bound to ask themselves whether they ended up in this group. They will see the short needles and the shallow needling, and a percentage of patients from this group will doubtlessly suspect that they are getting the sham treatment. The doubters will not show a powerful placebo response. Therefore, the average pain scores in this group will decrease – but only a little.

Group 1 will also be pleased to receive some treatment. As the therapists cannot be blinded, they will do their best to meet the high expectations of their patients. Consequently, they will benefit fully from the placebo effect of the intervention and the pain score of this group will decrease significantly.

So, now we can surely predict the most likely result of this trial without even conducting it. Assuming that acupuncture is a placebo-therapy, as many people do, we now see that group 3 will suffer the most pain. In comparison, groups 1 and 2 will show better outcomes.

Of course, the main question is, how do groups 1 and 2 compare to each other? After all, we designed our sham-controlled trial in order to answer exactly this issue: is acupuncture more than a placebo? As pointed out above, some patients in group 2 would have become suspicious and therefore would not have experienced the full placebo-response. This means that, provided the sample sizes are sufficiently large, there should be a significant difference between these two groups favouring real acupuncture over sham. In other words, our trial will conclude that acupuncture is better than placebo, even if acupuncture is a placebo.

THANK YOU FOR DOING THIS THOUGHT EXPERIMENT WITH ME.

Now I can tell you that it has a very real basis. The leading medical journal, JAMA, just published such a study and, to make matters worse, the trial was even sponsored by one of the most prestigious funding agencies: the NIH.

Here is the abstract:

___________________________________________________________________________

Musculoskeletal symptoms are the most common adverse effects of aromatase inhibitors and often result in therapy discontinuation. Small studies suggest that acupuncture may decrease aromatase inhibitor-related joint symptoms.

Objective:

To determine the effect of acupuncture in reducing aromatase inhibitor-related joint pain.

Design, Setting, and Patients:

Randomized clinical trial conducted at 11 academic centers and clinical sites in the United States from March 2012 to February 2017 (final date of follow-up, September 5, 2017). Eligible patients were postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer who were taking an aromatase inhibitor and scored at least 3 on the Brief Pain Inventory Worst Pain (BPI-WP) item (score range, 0-10; higher scores indicate greater pain).

Interventions:

Patients were randomized 2:1:1 to the true acupuncture (n = 110), sham acupuncture (n = 59), or waitlist control (n = 57) group. True acupuncture and sham acupuncture protocols consisted of 12 acupuncture sessions over 6 weeks (2 sessions per week), followed by 1 session per week for 6 weeks. The waitlist control group did not receive any intervention. All participants were offered 10 acupuncture sessions to be used between weeks 24 and 52.

Main Outcomes and Measures:

The primary end point was the 6-week BPI-WP score. Mean 6-week BPI-WP scores were compared by study group using linear regression, adjusted for baseline pain and stratification factors (clinically meaningful difference specified as 2 points).

Results:

Among 226 randomized patients (mean [SD] age, 60.7 [8.6] years; 88% white; mean [SD] baseline BPI-WP score, 6.6 [1.5]), 206 (91.1%) completed the trial. From baseline to 6 weeks, the mean observed BPI-WP score decreased by 2.05 points (reduced pain) in the true acupuncture group, by 1.07 points in the sham acupuncture group, and by 0.99 points in the waitlist control group. The adjusted difference for true acupuncture vs sham acupuncture was 0.92 points (95% CI, 0.20-1.65; P = .01) and for true acupuncture vs waitlist control was 0.96 points (95% CI, 0.24-1.67; P = .01). Patients in the true acupuncture group experienced more grade 1 bruising compared with patients in the sham acupuncture group (47% vs 25%; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance:

Among postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer and aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgias, true acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture or with waitlist control resulted in a statistically significant reduction in joint pain at 6 weeks, although the observed improvement was of uncertain clinical importance.

__________________________________________________________________________

Do you see how easy it is to deceive (almost) everyone with a trial that looks rigorous to (almost) everyone?

My lesson from all this is as follows: whether consciously or unconsciously, SCAM-researchers often build into their trials more or less well-hidden little loopholes that ensure they generate a positive outcome. Thus even a placebo can appear to be effective. They are true masters of producing false-positive findings which later become part of a meta-analysis which is, of course, equally false-positive. It is a great shame, in my view, that even top journals (in the above case JAMA) and prestigious funders (in the above case the NIH) cannot (or want not to?) see behind this type of trickery.