chiropractic

We have discussed the association between chiropractic an opioid use before. But the problem of causality remained unresolved. Perhaps this new paper can help? This retrospective cohort study with new onset back pain patients (2008-20013) examined the association of initial provider treatment with early and long-term opioid use in a national sample of patients with new-onset low back pain (LBP).

The researchers evaluated outpatient and inpatient claims from patient visits, pharmacy claims and inpatient and outpatient procedures with initial providers seen for new-onset LBP. The 216 504 patients were aged 18 years or older and had been diagnosed with new-onset LBP and were opioid-naïve were included. Participants had commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance. The primary independent variable was the type of initial healthcare provider including physicians and conservative therapists (physical therapists, chiropractors, acupuncturists). The main outcome measures were short-term opioid use (within 30 days of the index visit) following new LBP visit and long-term opioid use (starting within 60 days of the index date and either 120 or more days’ supply of opioids over 12 months, or 90 days or more supply of opioids and 10 or more opioid prescriptions over 12 months).

Short-term use of opioids was 22%. Patients who received initial treatment from chiropractors or physical therapists had decreased odds of short-term and long-term opioid use compared with those who received initial treatment from primary care physicians (PCPs) (adjusted OR (AOR) (95% CI) 0.10 (0.09 to 0.10) and 0.15 (0.13 to 0.17), respectively). Compared with PCP visits, initial chiropractic and physical therapy also were associated with decreased odds of long-term opioid use in a propensity score matched sample (AOR (95% CI) 0.21 (0.16 to 0.27) and 0.29 (0.12 to 0.69), respectively).

The authors concluded that initial visits to chiropractors or physical therapists is associated with substantially decreased early and long-term use of opioids. Incentivising use of conservative therapists may be a strategy to reduce risks of early and long-term opioid use.

Like in previous papers, the nature of the association remains unclear. Is it correlation or causation? It is not correct to conclude that initial visits to chiropractors or physical therapists is associated with substantially decreased early and long-term use of opioids, because this implies a causal relationship. Likewise, it is odd to claim that incentivising the use of chiros or physios may reduce the risk of opioid use. The only thing that reduces opioid use is opioid perscribing. The way to achieve this is to teach and train doctors adequately, I think.

Spinal epidural haematoma is a potentially serious condition that can occur due to trauma, such as spinal manipulation, particularly in the presence of a blood clotting abnormality. A case has been published of a patient who, after performing self-neck manipulation, suffered spinal epidural haematoma and subsequent paralysis of all 4 limbs.

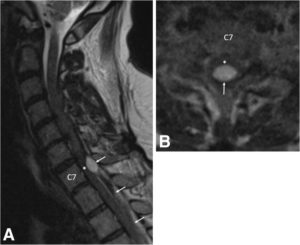

A 63-year-old man presented to the emergency department with worsening inter-scapular pain radiating to his neck one day after performing self-manipulation of his cervical spine. He was anti-coagulated with warfarin therapy for the management of his atrial fibrillation. Approximately 48 h after the manipulation, the patient became acutely quadriparetic and hypotensive. Urgent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a multilevel spinal epidural haematoma from the lower cervical to thoracic spine.

a Pre-operative sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the cervical spine demonstrates an epidural hematoma (arrows) with the cranial extent at the C6/7 level. The hematoma is mixed signal intensity, consistent with various stages of bleeding. Severe spinal cord (asterisk) compression is present at the C7 level. b Pre-operative axial T2-weighted MRI at the C7 level demonstrates a loculated epidural hematoma (arrow) compressing the spinal cord (asterisk). Due to the urgent nature of the MRI, image quality is degraded

With identification of an active bleed and an INR remaining close to 7.0, the patient’s hypercoaguable state was reversed prior to emergency surgery. The patient underwent partial C7, complete T1 and T2, and partial T3 bilateral laminectomy for evacuation of haematoma. Placement of an epidural drainage catheter was also performed.

During the first 6 days following surgery, the patient recovered some function of the upper and lower extremities while undergoing hospital-based physical therapy. Post-operative MRI showed resolution of the haematoma and cord compression without resultant cord damage.

The patient completed a 2-week course of acute interdisciplinary rehabilitation. The epidural drainage catheter remained in place for most of his post-operative stay. His neurogenic bladder with urinary retention resolved. At hospital discharge, the patient’s greatest deficits remained his fine motor skills to his right hand along with residual paraesthesia in his lower extremities. He also exhibited mild dyspraxia with finger-to-nose testing on the right and heel-to-shin testing bilaterally. The patient regained full manual muscle strength of all 4 extremities and ultimately returned to his baseline functional status, which included ambulating independently with a cane and independence with activities of daily living.

The authors concluded that partial C7, complete T1 and T2, and partial T3 bilateral laminectomy was performed for evacuation of the spinal epidural hematoma. Following a 2-week course of acute inpatient rehabilitation, the patient returned to his baseline functional status. This case highlights the risks of self-manipulation of the neck and potentially other activities that significantly stretch or apply torque to the cervical spine. It also presents a clinical scenario in which practitioners of spinal manipulation therapy should be aware of patients undergoing anticoagulation therapy.

In the present case, the spinal manipulation was self-inflicted. Usually it is performed by a chiropractor, and there are published case reports where chiropractic spinal manipulations have caused epidural haematoma. No matter who does this treatment, it is, I think, wise to consider the fact that the risks of spinal manipulations do not demonstrably outweigh its benefits.

Recently, I stumbled across this website and the following text:

“Measles are an implant Scientology can handle using New Era Dianetics,” said Scientology chiropractor Colonel Dr. Roberto Cadiz. “As a chiropractor, I see mock ups of so-called serious diseases all the time,” Dr. Cadiz remarked. “And fully 99% of the time these diseases are chronic subluxations caused by dangerous childhood vaccinations the Psychs force on everyone.” “Chiropractic adjustment, the Purification Rundown, CalMag, and Dianetics auditing are crucial parts of the treatment regimen for cancers, measles, etc. What you need to find are the words in the implant that turn the disease on. As LRH wrote of leukemia:

‘”Leukaemia is evidently psychosomatic in origin and at least eight cases of leukaemia had been treated successfully by Dianetics after medicine had traditionally given up. The source of leukaemia has been reported to be an engram containing the phrase ‘It turns my blood to water.’”

“When the preclear gives the exact words hidden in the implant during an auditing session the implant vanishes. The e-meter literally blows up and falls of the table. Of course, continued chiropractic adjustments for life are needed to keep these heavy engrams from going into restimulation. Ideally, chiropractic adjustments should be done three times a week to maintain optimal health.”

Yes, this is so far out, it could almost be a hoax. But I fear it is for real. In the past I have come across many similar statements by scientology chiros. This led me to wonder for some time now: is there a link between the two?

Come to think of it, chiropractic and scientology have a lot in common:

- they are both based on frightfully weird theories,

- they both are known use the e-meter (or derivatives of it);

- they are both akin to a religion or cult;

- they are both fiercely against drugs;

- they both feel pursued by the medical profession;

- they both promote detox;

- they both recommend useless supplements;

- they both tend to be anti-vax;

- they both have powerful lobby groups to support them;

- they both tend to react very aggressively to criticism.

One does not have to look far to find further links on the internet – there are virtually hundreds. Take this website, for instance:

Stewart Edrich thanks Scientology becaue it aligns perfectly with his practice of chiropractic and clinical nutrition because it covers your entire existence. Unfortunately for him, someone found this on the internet which destroys what little positive credbility he has through Scientology…

David Murdoch learned about Scientology at Palmer — “A group of us were having dinner and he remarked that a lot of the chiropractic management firms got their management data directly from L. Ron Hubbard.”

Or have a look here, here or here.

Or read reports like this one:

A South Florida chiropractic office has agreed to pay a $170,000 settlement to a group of former employees who claim they were forced to participate in Scientology practices.

Or this one:

A South Carolina chiropractor has been sued by a former employee for allegedly forcing sexual acts — and Scientology — on her, according to a report.

So, does any of this prove anything?

No!

Does it raise a suspicion that there might be a link?

Yes!

I would be delighted to hear from people who can enlighten me either way.

This systematic review was aimed at investigating the current evidence to determine whether there is an association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt.

Controlled studies, cohort studies, and case-control studies including adults with noncancer pain were eligible for inclusion. Studies reporting opioid receipt for both subjects who used chiropractic care and nonusers were included. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were completed independently by pairs of reviewers. Meta-analysis was performed and presented as an odds ratio with 95% confidence interval.

In all, 874 articles were identified. After detailed selection, 26 articles were reviewed in full, and 6 met the inclusion criteria. Five studies focused on back pain and one on neck pain. The prevalence of chiropractic care among patients with spinal pain varied between 11.3% and 51.3%. The proportion of patients receiving an opioid prescription was lower for chiropractic users (range = 12.3-57.6%) than nonusers (range = 31.2-65.9%). In a random-effects analysis, chiropractic users had a 64% lower odds of receiving an opioid prescription than nonusers (odds ratio = 0.36, 95% confidence interval = 0.30-0.43, P < 0.001, I2 = 92.8%).

The authors concluded that this review demonstrated an inverse association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt among patients with spinal pain. Further research is warranted to assess this association and the implications it may have for case management strategies to decrease opioid use.

These results are in line with a previous study showing that among New Hampshire adults with office visits for noncancer low-back pain, the likelihood of filling a prescription for an opioid analgesic was significantly lower for recipients of services delivered by doctors of chiropractic compared with nonrecipients. The underlying cause of this correlation remains unknown, indicating the need for further investigation.

The question is: what do such findings tell us?

I have no doubt that chiropractors will claim that using their services will reduce the opioid problem. But this is, of course, wishful thinking. The thing that will reduce it is not more chiro use but quite simply less opioid use!

The important thing to remember here is CORRELATION IS NOT CAUSATION!

People who drive a VW car are less likely to buy a Mercedes.

People who have ordered fish in a restaurant are unlikely to also order a steak.

People who use physiotherapy for back pain will probably use less opioids than those who don’t consult physios.

People who treat their back pain with massage therapy are less likely to also use opioids.

Etc.

Etc.

This is all very obvious, self-evident and perhaps even boring.

The most interesting finding here is in my view the fact that 31.2-65.9% of patients using chiropractic for their neck/back pain also took opioids. This seems to confirm what we often have discussed before:

CHIROPRACTIC TREATMENT IS NOT NEARLY AS EFFECTIVE AS CHIROS WANT US TO BELIEVE.

Spinal manipulation is a treatment employed by several professions, including physiotherapists and osteopaths; for chiropractors, it is the hallmark therapy.

- They use it for (almost) every patient.

- They use it for (almost) every condition.

- They have developed most of the techniques.

- Spinal manipulation is the focus of their education and training.

- All textbooks of chiropractic focus on spinal manipulation.

- Chiropractors are responsible for most of the research on spinal manipulation.

- Chiropractors are responsible for most of the adverse effects of spinal manipulation.

Spinal manipulation has traditionally involved an element of targeting the technique to a level of the spine where the proposed movement dysfunction is sited. This study evaluated the effects of a targeted manipulative thrust versus a thrust applied generally to the lumbar region.

Sixty patients with low back pain were randomly allocated to two groups: one group received a targeted manipulative thrust (n=29) and the other a general manipulation thrust (GT) (n=31) to the lumbar spine. Thrust was either localised to a clinician-defined symptomatic spinal level or an equal force was applied through the whole lumbosacral region. The investigators measured pressure-pain thresholds (PPTs) using algometry and muscle activity (magnitude of stretch reflex) via surface electromyography. Numerical ratings of pain and Oswestry Disability Index scores were collected.

Repeated measures of analysis of covariance revealed no between-group differences in self-reported pain or PPT for any of the muscles studied. The authors concluded that a GT procedure—applied without any specific targeting—was as effective in reducing participants’ pain scores as targeted approaches.

The authors point out that their data are similar to findings from a study undertaken with a younger, military sample, showing no significant difference in pain response to a general versus specific rotation, manipulation technique. They furthermore discuss that, if ‘targeted’ manipulation proves to be no better than ‘general’ manipulation (when there has been further research, more studies), it would challenge the need for some current training courses that involve comprehensive manual skill training and teaching of specific techniques. If simple SM interventions could be delivered with less training, than the targeted approach currently requires, it would mean a greater proportion of the population who have back pain could access those general manipulation techniques.

Assuming that the GT used in this trial was equivalent to a placebo control, another interpretation of these results is that the effects of spinal manipulation are largely or even entirely due to a placebo response. If this were confirmed in further studies, it would be yet one more point to argue that spinal manipulation is not a treatment of choice for back pain or any other condition.

A systematic review of the evidence for effectiveness and harms of specific spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) techniques for infants, children and adolescents has been published by Dutch researchers. I find it important to stress from the outset that the authors are not affiliated with chiropractic institutions and thus free from such conflicts of interest.

They searched electronic databases up to December 2017. Controlled studies, describing primary SMT treatment in infants (<1 year) and children/adolescents (1–18 years), were included to determine effectiveness. Controlled and observational studies and case reports were included to examine harms. One author screened titles and abstracts and two authors independently screened the full text of potentially eligible studies for inclusion. Two authors assessed risk of bias of included studies and quality of the body of evidence using the GRADE methodology. Data were described according to PRISMA guidelines and CONSORT and TIDieR checklists. If appropriate, random-effects meta-analysis was performed.

Of the 1,236 identified studies, 26 studies were eligible. In all but 3 studies, the therapists were chiropractors. Infants and children/adolescents were treated for various (non-)musculoskeletal indications, hypothesized to be related to spinal joint dysfunction. Studies examining the same population, indication and treatment comparison were scarce. Due to very low quality evidence, it is uncertain whether gentle, low-velocity mobilizations reduce complaints in infants with colic or torticollis, and whether high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulations reduce complaints in children/adolescents with autism, asthma, nocturnal enuresis, headache or idiopathic scoliosis. Five case reports described severe harms after HVLA manipulations in 4 infants and one child. Mild, transient harms were reported after gentle spinal mobilizations in infants and children, and could be interpreted as side effect of treatment.

The authors concluded that, based on GRADE methodology, we found the evidence was of very low quality; this prevented us from drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of specific SMT techniques in infants, children and adolescents. Outcomes in the included studies were mostly parent or patient-reported; studies did not report on intermediate outcomes to assess the effectiveness of SMT techniques in relation to the hypothesized spinal dysfunction. Severe harms were relatively scarce, poorly described and likely to be associated with underlying missed pathology. Gentle, low-velocity spinal mobilizations seem to be a safe treatment technique in infants, children and adolescents. We encourage future research to describe effectiveness and safety of specific SMT techniques instead of SMT as a general treatment approach.

We have often noted that, in chiropractic trials, harms are often not mentioned (a fact that constitutes a violation of research ethics). This was again confirmed in the present review; only 4 of the controlled clinical trials reported such information. This means harms cannot be evaluated by reviewing such studies. One important strength of this review is that the authors realised this problem and thus included other research papers for assessing the risks of SMT. Consequently, they found considerable potential for harm and stress that under-reporting remains a serious issue.

Another problem with SMT papers is their often very poor methodological quality. The authors of the new review make this point very clearly and call for more rigorous research. On this blog, I have repeatedly shown that research by chiropractors resembles more a promotional exercise than science. If this field wants to ever go anywhere, if needs to adopt rigorous science and forget about its determination to advance the business of chiropractors.

I feel it is important to point out that all of this has been known for at least one decade (even though it has never been documented so scholarly as in this new review). In fact, when in 2008, my friend and co-author Simon Singh, published that chiropractors ‘happily promote bogus treatments’ for children, he was sued for libel. Since then, I have been legally challenged twice by chiropractors for my continued critical stance on chiropractic. So, essentially nothing has changed; I certainly do not see the will of leading chiropractic bodies to bring their house in order.

May I therefore once again suggest that chiropractors (and other spinal manipulators) across the world, instead of aggressing their critics, finally get their act together. Until we have conclusive data showing that SMT does more good than harm to kids, the right thing to do is this: BEHAVE LIKE ETHICAL HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS: BE HONEST ABOUT THE EVIDENCE, STOP MISLEADING PARENTS AND STOP TREATING THEIR CHILDREN!

The World Federation of Chiropractic (WFC) claim to have been at the forefront of the global development of chiropractic. Representing the interests of the profession in over 90 countries worldwide, the WFC has advocated, defended and promoted the profession across its 7 world regions. Now, the WFC have formulated 20 principles setting out who they are, what they stand for, and how chiropractic as a global health profession can, in their view, impact on nations so that populations can thrive and reach their full potential. Here are the 20 principles (in italics followed by some brief comments by me in normal print):

1. We envision a world where people of all ages, in all countries, can access the benefits of chiropractic.

That means babies and infants! What about the evidence?

2. We are driven by our mission to advance awareness, utilization and integration of chiropractic internationally.

One could almost suspect that the drive is motivated by misleading the public about the risks and benefits of spinal manipulation for financial gain.

3. We believe that science and research should inform care and policy decisions and support calls for wider access to chiropractic.

If science and research truly did inform care, it would soon be chiropractic-free.

4. We maintain that chiropractic extends beyond the care of patients to the promotion of better health and the wellbeing of our communities.

The best example to show that this statement is a politically correct platitude is the fact that so many chiropractors are (educated to become) convinced that vaccinations are undesirable or harmful.

5. We champion the rights of chiropractors to practice according to their training and expertise.

I am not sure what this means. Could it mean that they must practice according to their training and expertise, even if both fly in the face of the evidence?

6. We promote evidence-based practice: integrating individual clinical expertise, the best available evidence from clinical research, and the values and preferences of patients.

So far, I have seen little to convince me that chiropractors care a hoot about the best available evidence and plenty to fear that they supress it, if it does not enhance their business.

7. We are committed to supporting our member national associations through advocacy and sharing best practices for the benefit of patients and society.

Much more likely for the benefit of chiropractors, I suspect.

8. We acknowledge the role of chiropractic care, including the chiropractic adjustment, to enhance function, improve mobility, relieve pain and optimize wellbeing.

Of course, you have to pretend that chiropractic adjustments (of subluxations) are useful. However, evidence would be better than pretence.

9. We support research that investigates the methods, mechanisms, and outcomes of chiropractic care for the benefit of patients, and the translation of research outcomes into clinical practice.

And if it turns out to be to the detriment of the patient? It seems to me that you seem to know the result of the research before you started it. That does not bode well for its reliability.

10. We believe that chiropractors are important members of a patient’s healthcare team and that interprofessional approaches best facilitate optimum outcomes.

Of course you do believe that. Why don’t you show us some evidence that your belief is true?

11. We believe that chiropractors should be responsible public health advocates to improve the wellbeing of the communities they serve.

Of course you do believe that. But, in fact, many chiropractors are actively undermining the most important public health measure, vaccination.

12. We celebrate individual and professional diversity and equality of opportunity and represent these values throughout our Board and committees.

What you should be celebrating is critical assessment of all chiropractic concepts. This is the only way to make progress and safeguard the interests of the patient.

13. We believe that patients have a fundamental right to ethical, professional care and the protection of enforceable regulation in upholding good conduct and practice.

The truth is that many chiropractors violate medical ethics on a daily basis, for instance, by not obtaining fully informed consent.

14. We serve the global profession by promoting collaboration between and amongst organizations and individuals who support the vision, mission, values and objectives of the WFC.

Yes, those who support your vision, mission, values and objectives are your friends; those who dare criticising them are your enemies. It seems far from you to realise that criticism generates progress, perhaps not for the WFC, but for the patient.

15. We support high standards of chiropractic education that empower graduates to serve their patients and communities as high value, trusted health professionals.

For instance, by educating students to become anti-vaxxers or by teaching them obsolete concepts such as adjustment of subluxation?

16. We believe in nurturing, supporting, mentoring and empowering students and early career chiropractors.

You are surpassing yourself in the formulation of platitudes.

17. We are committed to the delivery of congresses and events that inspire, challenge, educate, inform and grow the profession through respectful discourse and positive professional development.

You are surpassing yourself in the formulation of platitudes.

18. We believe in continuously improving our understanding of the biomechanical, neurophysiological, psychosocial and general health effects of chiropractic care.

Even if there are no health effects?!?

19. We advocate for public statements and claims of effectiveness for chiropractic care that are honest, legal, decent and truthful.

Advocating claims of effectiveness in the absence of proof of effectiveness is neither honest, legal, decent or truthful, in my view.

20. We commit to an EPIC future for chiropractic: evidence-based, people-centered, interprofessional and collaborative.

And what do you propose to do with the increasing mountain of evidence suggesting that your spinal adjustments are not evidence-based as well as harmful to the health and wallets of your patients?

________________________________________________________________

What do I take out of all this? Not a lot!

Perhaps mainly this: the WFC is correct when stating that, in the interests of the profession in over 90 countries worldwide, the WFC has advocated, defended and promoted the profession across its 7 world regions. What is missing here is a small but important addition to the sentence: in the interests of the profession and against the interest of patients, consumers or public health in over 90 countries worldwide, the WFC has advocated, defended and promoted the profession across its 7 world regions.

Controlled clinical trials are methods for testing whether a treatment works better than whatever the control group is treated with (placebo, a standard therapy, or nothing at all). In order to minimise bias, they ought to be randomised. This means that the allocation of patients to the experimental and the control group must not be by choice but by chance. In the simplest case, a coin might be thrown – heads would signal one, tails the other group.

In so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) where preferences and expectations tend to be powerful, randomisation is particularly important. Without randomisation, the preference of patients for one or the other group would have considerable influence on the result. An ineffective therapy might thus appear to be effective in a biased study. The randomised clinical trial (RCT) is therefore seen as a ‘gold standard’ test of effectiveness, and most researchers of SCAM have realised that they ought to produce such evidence, if they want to be taken seriously.

But, knowingly or not, they often fool the system. There are many ways to conduct RCTs that are only seemingly rigorous but, in fact, are mere tricks to make an ineffective SCAM look effective. On this blog, I have often mentioned the A+B versus B study design which can achieve exactly that. Today, I want to discuss another way in which SCAM researchers can fool us (and even themselves) with seemingly rigorous studies: the de-randomised clinical trial (dRCT).

The trick is to use random allocation to the two study groups as described above; this means the researcher can proudly and honestly present his study as an RCT with all the kudos these three letters seem to afford. And subsequent to this randomisation process, the SCAM researcher simply de-randomises the two groups.

To understand how this is done, we need first to be clear about the purpose of randomisation. If done well, it generates two groups of patients that are similar in all factors that might impact on the results of the study. Perhaps the most obvious factor is disease severity; one could easily use other methods to make sure that both groups of an RCT are equally severely ill. But there are many other factors which we cannot always quantify or even know about. By using randomisation, we make sure that there is an similar distribution of ALL of them in the two study groups, even those factors we are not even aware of.

De-randomisation is thus a process whereby the two previously similar groups are made to differ in terms of any factor that impacts on the results of the trial. In SCAM, this is often surprisingly simple.

Let’s use a concrete example. For our study of spiritual healing, the 5 healers had opted during the planning period of the study to treat both the experimental group and the control group. In the experimental group, they wanted to use their full healing power, while in the control group they would not employ it (switch it off, so to speak). It was clear to me that this was likely to lead to de-randomisation: the healers would have (inadvertently or deliberately) behaved differently towards the two groups of patients. Before and during the therapy, they would have raised the expectation of the verum group (via verbal and non-verbal communication), while sending out the opposite signals to the control group. Thus the two previously equal groups would have become unequal in terms of their expectation. And who can deny that expectation is a major determinant of the outcome? Or who can deny that experienced clinicians can manipulate their patients’ expectation?

For our healing study, we therefore chose a different design and did all we could to keep the two groups comparable. Its findings thus turned out to show that healing is not more effective than placebo (It was concluded that a specific effect of face-to-face or distant healing on chronic pain could not be demonstrated over eight treatment sessions in these patients.). Had we not taken these precautions, I am sure the results would have been very different.

In RCTs of some SCAMs, this de-randomisation is difficult to avoid. Think of acupuncture, for instance. Even when using sham needles that do not penetrate the skin, the therapist is aware of the group allocation. Hoping to prove that his beloved acupuncture can be proven to work, acupuncturists will almost automatically de-randomise their patients before and during the therapy in the way described above. This is, I think, the main reason why some of the acupuncture RCTs using non-penetrating sham devices or similar sham-acupuncture methods suggest that acupuncture is more than a placebo therapy. Similar arguments also apply to many other SCAMs, including for instance chiropractic.

There are several ways of minimising this de-randomisation phenomenon. But the only sure way to avoid this de-randomisation is to blind not just the patient but also the therapists (and to check whether both remained blind throughout the study). And that is often not possible or exceedingly difficult in trials of SCAM. Therefore, I suggest we should always keep de-randomisation in mind. Whenever we are confronted with an RCT that suggest a result that is less than plausible, de-randomisation might be a possible explanation.

Myelopathy is defined as any neurologic deficit related to the spinal cord. When due to trauma, it is known as (acute) spinal cord injury. When caused by inflammatory, it is known as myelitis. Disease that is vascular in nature is known as vascular myelopathy.

The symptoms of myelopathy include:

- Pain in the neck, arm, leg or lower back

- Muscle weakness

- Difficulty with fine motor skills, such as writing or buttoning a shirt

- Difficulty walking

- Loss of urinary or bowel control

- Issues with balance and coordination

The causes of myelopathy include:

- Tumours that put pressure on the spinal cord

- Bone spurs

- A dislocation fracture

- Autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis

- Congenital abnormality

- A traumatic injury

This review presents a series of cases with cervical spine injury and myelopathy following therapeutic manipulation of the neck, and examines their clinical course and neurological outcome.

Its authors conducted a search for patients who developed neurological symptoms due to cervical spinal cord injury following neck SMT in the database of a spinal unit in a tertiary hospital between the years 2008 and 2018. Patients with vertebral artery dissections were excluded. Patients were assessed for the clinical course and deterioration, type of manipulation used and subsequent management.

A total of four patients were identified, two men and two women, aged between 32 and 66 years. In three patients neurological deterioration appeared after chiropractic adjustment and in one patient after tuina therapy. The patients had experienced symptoms within one day to one week after neck manipulation. The four patients had signs of:

- central cord syndrome,

- spastic quadriparesis,

- spastic quadriparesis,

- radiculopathy and myelomalacia.

Three patients were managed with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion while one patient declined surgical treatment.

The authors note that their data cannot determine whether the spinal cord dysfunction was caused my the spinal manipulations or were pre-existing problems which were aggravated by the treatments. They recommend that assessment for subjective and objective evidence of cervical myelopathy should be performed prior to cervical manipulation, and suspected myelopathic patients should be sent for further workup by a specialist familiar with cervical myelopathy, such as a neurologist, a neurosurgeon or orthopaedic surgeon who specializes in spinal surgery. They also state that manipulation therapy remains an important and generally safe treatment modality for a variety of cervical complaints. Their review, the authors stress, does not intend to discard the role of spinal manipulation as a significant part in the management of patients with neck related symptoms, rather it is meant to draw attention to the need for careful clinical and imaging investigation before treatment. This recommendation might be medically justified, yet one could argue that it is less than practical.

This paper from Israel is interesting in that it discloses possible complications of cervical manipulation. It confirms that chiropractors are most frequently implicated and that – as in our survey – under-reporting is exactly 100% (none of the cases identified by the retrospective chart review had been previously reported).

In light of this, some of the affirmations of the authors are bizarre. In particular, I ask myself how they can claim that cervical manipulation is a ‘generally safe’ treatment. With under-reporting at such high levels, the only thing one can say with certainty is that serious complications do happen and nobody can be sure how frequently they occur.

“There is a ton of chiropractor journals. If you want evidence then read some.”

This was the comment by a defender of chiropractic to a recent post of mine. And it’s true, of course: there are quite a few chiro journals, but are they a reliable source of information?

One way of quantifying the reliability of medical journals is to calculate what percentage of its published articles arrive at negative conclusion. In the extreme instance of a journal publishing nothing but positive results, we cannot assume that it is a credible publication. In this case, it would be not a scientific journal at all, but it would be akin to a promotional rag.

Back in 1997, we published our first analysis of journals of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). It showed that just 1% of the papers published in SCAM journals reported findings that were not positive. In the years that followed, we confirmed this deplorable state of affairs repeatedly, and on this blog I have shown that the relatively new EBCAM journal is similarly dubious.

But these were not journals focussing specifically on chiropractic. Therefore, the question whether chiro journals are any different from the rest of SCAM is as yet unanswered. Enough reason for me to bite the bullet and test this hypothesis. I thus went on Medline and assessed all the articles published in 2018 in two of the leading chiro journals.

- JOURNAL OF CHIROPRACTIC MEDICINE (JCM)

- CHIROPRACTIC AND MANUAL THERAPY (CMT)

I evaluated them according to

- TYPE OF ARTICLE

- DIRECTION OF CONCLUSION

The results of my analysis are as follows:

- The JCM published 39 Medline-listed papers in 2018.

- The CMT published 50 such papers in 2018.

- Together, the 2 journals published:

- 18 surveys,

- 17 case reports,

- 10 reviews,

- 8 diagnostic papers,

- 7 pilot studies,

- 4 protocols,

- 2 RCTs,

- 2 non-randomised trials,

- 2 case-series,

- the rest are miscellaneous types of articles.

4. None of these papers arrived at a conclusion that is negative or contrary to chiropractors’ current belief in chiropractic care. The percentage of publishing negative findings is thus exactly 0%, a figure that is almost identical to the 1% we found for SCAM journals in 1997.

I conclude: these results suggest that the hypothesis of chiro journals publishing reliable information is not based on sound evidence.