Chinese studies

There are skeptics who keep claiming that there is no research in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). And there are plenty of SCAM enthusiasts who claim that there is an abundance of good research in SCAM.

Who is right and who is wrong?

I submit that both camps are incorrect.

To demonstrate the volume of SCAM research I looked into Medline to find the number of papers published in 2020 for the SCAMs listed below:

- acupuncture 2 752

- anthroposophic medicine 29

- aromatherapy 173

- Ayurvedic medicine 183

- chiropractic 426

- dietary supplement 5 739

- essential oil 2 439

- herbal medicine 5 081

- homeopathy 154

- iridology 0

- Kampo medicine 132

- massage 824

- meditation 780

- mind-body therapies 968

- music therapy 539

- naturopathy 68

- osteopathic manipulation 71

- Pilates 97

- qigong 97

- reiki 133

- tai chi 397

- Traditional Chinese Medicine 15 277

- yoga 698

I think the list proves anyone wrong who claims there is no (or very little) research into SCAM.

As to the enthusiasts who claim that there is plenty of good evidence, I am afraid, I disagree with them too. The above-quoted numbers are perhaps impressive to some SCAM proponents, but they are not large. To make my point more clearly, let me show you the 2020 volumes for a few topics in conventional medicine:

- psychiatry 668,492

- biologicals 300,679

- chemotherapy 109,869

- radiotherapy 17,964

- rehabilitation 21,751

- rehabilitation medicine 21,751

- surgery 256,958

I think we can agree that these figures make the SCAM numbers look pitifully small.

But the more important point is, I think, not the quantity but the quality of the SCAM research. As this whole blog is about the often dismal rigor of SCAM research, I do surely not need to produce further evidence to convince you that it is poor, often even very poor.

So, both camps tend to be incorrect when they speak about SCAM research. The truth is that there is quite a lot, but sadly reliable studies are like gold dust.

But actually, when I started writing this post and doing all these Medline searches to produce the above-listed volumes of SCAM research, I was thinking of a different subject entirely. I wanted to see which areas of SCAM were research-active and which are not. This is why I chose terms for my list that do not overlap with others (yet we need to realize that the figures are not precise due to misclassification and other factors). And in this respect, the list is interesting too, I find.

It identifies the SCAMs that are remarkably research-inactive:

- anthroposophic medicine

- iridology

- naturopathy

- osteopathy

- Pilates

- qigong

Perhaps more interesting are the areas that show a relatively high research activity:

- acupuncture

- dietary supplements

- essential oils

- herbal medicine

- massage

- meditation

- mind-body therapies

- TCM

- yoga

This, in turn, suggests two things:

- It is not true that only commercial interests drive research activity.

- The Chinese (TCM and acupuncture) are pushing the ferociously hard to conquer SCAM research.

The last point is worrying, in my view, because we know from several independent studies that Chinese studies are often the flimsiest and least reliable of all the SCAM literature. As I have suggested recently, the unreliability of SCAM research might one day be its undoing: This self-destructive course of SCAM might be applauded by some skeptics. However, if you believe (as I do) that there are a few good things to be found in SCAM, this development can only be regrettable. I fear that the growing dominance of Chinese research will help to speed up this process.

Tuina is a massage therapy that originates from Traditional Chinese Medicine. Many of the techniques used in tuina resemble those of a western massage like gliding, kneading, vibration, tapping, friction, pulling, rolling, pressing, and shaking. Tuina involves a range of manipulations usually performed by the therapist’s finger, hand, elbow, knee, or foot. They are applied to muscle or soft tissue at specific locations of the body.

The aim of Tuina is to enhance the flow of the ‘vital energy’ or ‘chi’, that is alleged to control our health. Proponents of the therapy recommend Tuina for a range of conditions, including paediatric ones. Paediatric Tuina has been widely used in children with acute diarrhea in China. However, due to a lack of high-quality clinical evidence, the benefit of Tuina is not clear.

This study aimed to assess the effect of paediatric Tuina compared with sham Tuina as add-on therapy in addition to usual care for 0-6-year-old children with acute diarrhea.

Eighty-six participants aged 0-6 years with acute diarrhea were randomized to receive Tuina plus usual care (n = 43) or sham Tuina plus usual care (n = 43). The primary outcomes were days of diarrhea from baseline and times of diarrhea on day 3. Secondary outcomes included a global change rating (GCR) and the number of days when the stool characteristics returned to normal. Adverse events were assessed.

Tuina treatment in the intervention group was performed on the surface of the children’s body using moderate pressure (Fig. 1a). Tuina treatment in the control group was different: the therapist used one hand to hold the child’s hand or put one hand on the child’s body, while the other hand performed manipulations on the therapist’s own hand instead of the child’s hand or body (Fig. (Fig.11b).

Tuina was associated with a reduction in times of diarrhea on day 3 compared with sham Tuina in both ITT and per-protocol analyses. However, the results were not significant when adjusted for social-demographic and clinical characteristics. No significant difference was found between groups in days of diarrhea, global change rating, or number of days when the stool characteristics returned to normal.

The authors concluded that in children aged 0-6 years with acute diarrhea, pediatric Tuina showed significant effects in terms of reducing times of diarrhea compared with sham Tuina. Studies with larger sample sizes and adjusted trial designs are warranted to further evaluate the effect of pediatric Tuina therapy.

This study was well-reported and has interesting features, such as the attempt to use a placebo control and blinding (whether blinding was successful is a different matter and was not tested in the trial). It is, therefore, all the more surprising that the essentially negative result is turned into a positive one. After adjustment, the differences disappear (a fact which the authors hardly mention in the paper), which means they are not due to the treatment but to group differences and confounding. This, in turn, means that the study shows not the effectiveness but the ineffectiveness of Tuina.

The state of acupuncture research has long puzzled me. The first thing that would strike who looks at it is its phenomenal increase:

- Until around the year 2000, Medline listed about 200 papers per year on the subject.

- From 2005, there was a steep, near-linear increase.

- It peaked in 2020 when we had a record-breaking 20515 acupuncture papers currently listed in Medline.

Which this amount of research, one would expect to get somewhere. In particular, one would hope to slowly know whether acupuncture works and, if so, for which conditions. But this is not the case.

On the contrary, the acupuncture literature is a complete mess in which it gets more and more difficult to differentiate the reliable from the unreliable, the useful from the redundant, and the truth from the lies. Because of this profound confusion, acupuncture fans are able to claim that their pet-therapy is demonstrably effective for a wide range of conditions, while skeptics insist it is a theatrical placebo. The consumer might listen in bewilderment.

Yesterday (18/1/2021), I had a quick (actually, it was not that quick after all) look into what Medline currently lists in terms of new acupuncture research published in 2021 and found a few other things that are remarkable:

- There were already 100 papers dated 2021 (today, there were even 118); that corresponds to about 5 new articles per day and makes acupuncture one of the most research-active areas of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

- Of these 100 papers, only 7 were clinical trials (CTs). In my view, clinical trials would be more important than any other type of research on acupuncture. To see that they amount to just 7% of the total is therefore disappointing.

- Twelve papers were systematic reviews (SRs). It is odd, I find, to see almost twice the amount of SRs than CTs.

- Eighteen papers referred to protocols of studies of SRs. In particular protocols of SRs are useless in my view. It seems to me that the explanation for this plethora of published protocols might be the fact that Chinese researchers are extremely keen to get papers into Western journals; it is an essential boost to their careers.

- Seven papers were surveys. This multitude of survey research is typical for all types of SCAM.

- Twenty-four articles were on basic research. I find basic research into an ancient therapy of questionable clinical use more than a bit strange.

- The rest of the articles were other types of publications and a few were misclassified.

- The vast majority (n = 81) of the 100 papers were authored exclusively by Chinese researchers (and a few Korean). In view of the fact that it has been shown repeatedly that practically all acupuncture studies from China report positive results and that data fabrication seems rife in China, this dominance of China could be concerning indeed.

Yes, I find all this quite concerning. I feel that we are swamped with plenty of pseudo-research on acupuncture that is of doubtful (in many cases very doubtful) reliability. Eventually, this will create an overall picture for the public that is misleading to the extreme (to check the validity of the original research is a monster task and way beyond what even an interested layperson can do).

And what might be the solution? I am not sure I have one. But for starters, I think, that journal editors should get a lot more discerning when it comes to article submissions from (Chinese) acupuncture researchers. My advice to them and everyone else:

if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is!

Bloodletting has been used for centuries in many cultures. Its principle, it was assumed, consisted in re-balancing the body’s four humours. Bloodletting had a detrimental effect on most diseases and must have killed millions. It is a good historical example of the harm that ensues, if healthcare adheres to dogma. Today, we know that bloodletting is useful only in rare conditions such as polycythaemia vera or haemochromatosis (and some 30 years ago, a variation of bloodletting, isovolaemic haemodilution, was being discussed as a treatment for circulatory diseases such as intermittent claudication or stroke).

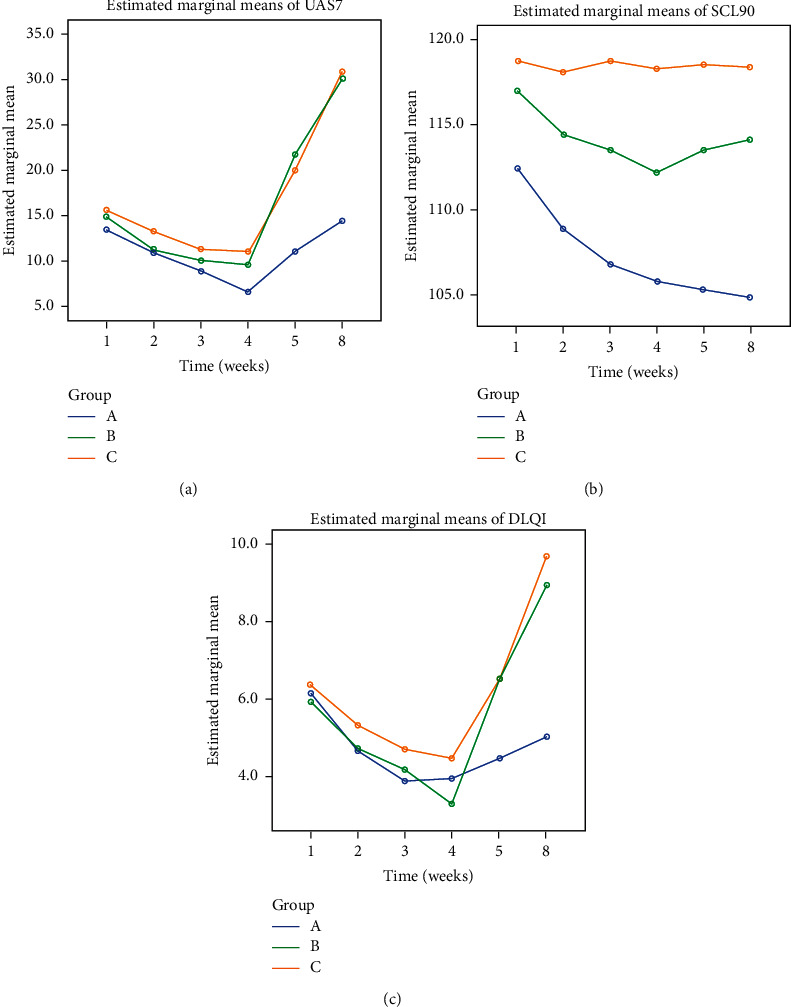

Yet, in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), there are some practitioners who seem to find it hard to concede that ancient treatments might be not as good as they think. Thus, bloodletting has survived in this realm as a therapy for a wide range of conditions. This study assessed the efficacy of bloodletting therapy (acupoint pricking and cupping) in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) in a randomized, control, parallel-group trial.

A total of 174 patients with CIU were randomized into three groups:

- group A was treated with bloodletting therapy and ebastine (an anti-histamine),

- group B was treated with placebo treatment (acupoint pseudopricking and cupping) and ebastine,

- group C was treated with ebastine only.

The treatment period lasted 4 weeks. An intention-to-treat analysis was conducted, and the primary outcome was the effective rate of UAS7 score being reduced to 7 or below after treatment phase.

The effective rates at the end of treatment phase were different among the three groups, which were

- 73.7% in group A,

- 45.6% in group B,

- and 42.9% in group C.

Multiple analysis indicated differences between groups A and B (P < 0.0125) and groups A and C (P < 0.0125) and no difference between groups B and C (P > 0.0125). No severe bloodletting therapy-related adverse events were observed.

The authors concluded that one month of bloodletting therapy combined with ebastine is clinically beneficial compared with placebo treatment combined with ebastine and treatment with ebastine only. Thus, bloodletting therapy can be an effective complementary treatment in CIU.

Amazed?

Me too!

How on earth might bloodletting help for CIU? Luckily, the authors have an answer to this question:

The clinical feature of urticaria with wheals and pruritus coming and going quickly is the manifestation of wind-evil that lurks in and circulates with blood. Hence, in the treatment of urticaria, dispersing wind is the one of the principle methods, and treating blood before wind is an important procedure because when blood flows fluently , wind-evil will resolve spontaneously. Bloodletting therapy is a direct and effective way of regulating blood.

You see, it’s all perfectly clear!

In this case, the results must be true. And the argument that patients might have known in which treatment group they had ended up (and were thus not blinded) can be discarded.

Acupuncture-moxibustion therapy (AMT) is a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that has been used for centuries in treatment of numerous diseases. Some enthusiasts even seem to advocate it for chemotherapy-induced leukopenia (CIL) The purpose of this review was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture-moxibustion therapy in treating CIL.

Relevant studies were searched in 9 databases up to September 19, 2020. Two reviewers independently screened the studies for eligibility, extracted data, and assessed the methodological quality of selected studies. Meta-analysis of the pooled mean difference (MD) and risk ratio (RR) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Seventeen studies (1206 patients) were included, and the overall quality of the included studies was moderate. In comparison with medical therapy, AMT has a better clinical efficacy for CIL (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17-1.32; P < 0.00001) and presents advantages in increasing leukocyte count (MD, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.67-1.53; P < 0.00001). Also, the statistical results show that AMT performs better in improving the CIL patients’ Karnofsky performance score (MD, 5.92; 95% CI, 3.03-8.81; P < 0.00001).

The authors concluded that this systematic review and meta-analysis provides updated evidence that AMT is a safe and effective alternative for the patients who suffered from CIL.

A CIL is a serious complication. If I ever were afflicted by it, I would swiftly send any acupuncturist approaching my sickbed packing.

But this is not an evidence-based attitude!!!, I hear some TCM-fans mutter. What more do you want that a systematic review showing it works?

I beg to differ. Why? Because the ‘evidence’ is hardly what critical thinkers can accept as evidence. Have a look at the list of the primary studies included in this review:

- Lin Z. T., Wang Q., Yu Y. N., Lu J. S. Clinical observation of post-chemotherapy-leukopenia treated with ShenMai injectionon ST36. World Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine. 2010;5(10):873–876. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Clinical Observation of Acupoint Moxibustion on Leukopenia Caused by Chemotherapy. Beijing, China: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J. Y. Coupling of Yin and Yang between Ginger Moxibustion Improve the Clinical Effect of the Treatment of Chemotherapy Adverse Reaction. Henan, China: Henan University of Chinese Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu D. R., Lu D. X., Wei M., et al. Acupoint injection with addie injection for patients of nausea and vomiting with cisplatin induced by chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2013;29(10):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. E. The Clinical Observation on Treatment of Leukopenia after Chemotherapy with Needle Warming Moxibustion. Hubei, China: Hubei University of Chinese Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. H., Chi C. Y., Zhang C. Y. Clinical effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on leukopenia after chemotherapy of malignant tumor. Guide of China Medicine. 2014;12(12) [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. N., Zhang W. X., Gu Q. H., Jiao J. P., Liu L., Wei P. K. Protection of herb-partitioned moxibustion on bone marrow suppression of gastric cancer patients in chemotherapy period. Chinese Archives of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2014;32(12):110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. The Clinical Research on Myelosuppression and Quality of Life after Chemotherapy Treated by Grain-Sized Moxibustion. Nanjing, China: Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Lin H., Zhang L., Fan Z. N., Zhang Z. L. Effective research on treating leukopenia following chemotherapy by moxibustion. Clinical Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2015;7(10):35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. W., Wang J. D., Zhao C. Y. Effect of acupuncture on the first WBC reduction after chemotherapy for breast cancer. Beijing Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;35(8):777–779. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D. L., Lu H. Y., Lu Y. Y., Wu L. J. Clinical observation of Qi-blood-supplementing needling for leukopenia after chemotherapy for breast cancer. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2016;35(8):964–966. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xu G. Y. Observation on the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia by moxibustion therapy. Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;51(8):p. 600. [Google Scholar]

- Mo T., Tian H., Yue S. B., Fan Z. N., Zhang Z. L. Clinical observation of acupoint moxibustion on leukocytopenia caused by tumor chemotherapy. World Chinese Medicine. 2016;11(10):2120–2122. [Google Scholar]

- Nie C. M. Nursing observation of acupoint moxibustion in the treatment of leucopenia after chemotherapy. Today Nurse. 2017;4:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. Y. Clinical Research on Post-chemotherapy-leukopenia with Spleen-Kidney Yang Deficiency in Colorectal Cancer Treated with Point-Injection. Yunnan, China: Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y. Q, Zhang M. Q, Zhang B. C. Prevention and treatment of leucocytopenia after chemotherapy in patients with malignant tumor with ginger partitioned moxibustion. Chinese Medicine Modern Distance Education of China. 2018;16(21):135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. C., Lian M. J., Miao F. G. Clinical observation of fuzheng moxibustion combined with wenyang shengbai decoction in the treatment of 80 cases of leukopenia after chemotherapy. Hunan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2019;35(3):64–66. [Google Scholar]

Notice anything peculiar?

- The studies are all from China where data fabrication was reported to be rife.

- They are mostly unavailable for checking (why the published adds links that go nowhere is beyond me).

- Many do not look at all like randomised clinical trials (which, according to the authors, was an inclusion criterion).

- Many do not look as though their primary endpoint was the leukocyte count (which, according to the authors, was another inclusion criterion).

Intriguingly, the authors conclude that AMT is not just effective but also ‘safe’. How do they know? According to their own data extraction table, most studies failed to mention adverse effects. And how exactly is acupuncture supposed to increase my leukocyte count? Here is what the authors offer as a mode of action:

I think it is high time that we stop tolerating that the medical literature gets polluted with such nonsense (helped, of course, by journals that are beyond the pale) – someone might actually believe it, in which case it would surely hasten the death of vulnerable patients.

Some consumers believe that research is by definition reliable, and patients are even more prone to this error. When they read or hear that ‘RESEARCH HAS SHOWN…’ or that ‘A RECENT STUDY HAS DEMONSTRATED…’, they usually trust the statements that follow. But is this trust in research and researchers justified? During 25 years that I have been involved in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), I have encountered numerous instances which make me doubt. In this post, I will briefly discuss some the many ways in which consumers can be mislead by apparently sound evidence (for an explanation as to what is and what isn’t evidence, see here).

ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE

I have just finished reading a book by a German Heilpraktiker that is entirely dedicated to SCAM. In it, the author makes hundreds of statements and presents them as evidence-based facts. To many lay people or consumers, this will look convincing, I am sure. Yet, it has one fatal defect: the author fails to offer any real evidence that would back up his statements. The only references provided were those of other books which are equally evidence-free. This popular technique of making unsupported claims allows the author to make assertions without any checks and balances. A lay person is usually unable or unwilling to differentiate such fabulations from evidence, and this technique is thus easy and poular for misleading us about SCAM.

FAKE-EVIDENCE

On this blog, we have encountered this phenomenon ad nauseam: a commentator makes a claim and supports it with some seemingly sound evidence, often from well-respected sources. The few of us who bother to read the referenced articles quickly discover that they do not say what the commentator claimed. This method relies on the reader beeing easily bowled over by some pretend-evidence. As many consumers cannot be bothered to look beyond the smokescreen supplied by such pretenders, the method usually works surprisingly well.

An example: Vidatox is a homeopathic cancer ‘cure’ from Cuba. The Vidatox website clains that it is effective for many cancers. Considering how sensational this claim is, one would expect to find plenty of published articles on Vidatox. However, a Medline search resulted in one paper on the subject. Its authors drew the following conclusion: Our results suggest that the concentration of Vidatox used in the present study has not anti-neoplastic effects and care must be taken in hiring Vidatox in patients with HCC.

The question one often has to ask is this: where is the line between misleading research and fraud?

SURVEYS

There is no area in healthcare that produces more surveys than SCAM. About 500 surveys are published every year! This ‘survey-mania’ has a purpose: it promotes a positive message about SCAM which hypothesis-testing research rarely does.

For a typical SCAM survey, a team of enthusiastic researchers might put together a few questions and design a questionnaire to find out what percentage of a group of individuals have tried SCAM in the past. Subsequently, the investigators might get one or two hundred responses. They then calculate simple descriptive statistics and demonstrate that xy % use SCAM. This finding eventually gets published in one of the many third-rate SCAM journals. The implication then is that, if SCAM is so popular, it must be good, and if it’s good, the public purse should pay for it. Few consumers would realise that this conclusion is little more that a fallacious appeal to popularity.

AVOIDING THE QUESTION

Another popular way of SCAM researchers to mislead the public is to avoid the research questions that matter. For instance, few experts would deny that one of the most urgent issues in chiropractic relates to the risk of spinal manipulations. One would therefore expect that a sizable proportion of the currently published chiropractic research is dedicated to it. Yet, the opposite is the case. Medline currently lists more than 3 000 papers on ‘chiropractic’, but only 17 on ‘chiropractic, harm’.

PILOT-STUDIES

A pilot study is a small scale preliminary study conducted in order to evaluate feasibility, time, cost, adverse events, and improve upon the study design prior to performance of a full-scale research project. Yet, the elementary preconditions are not fulfilled by the plethora of SCAM pilot studies that are currently being published. True pilot studies of SCAM are, in fact, very rare. The reason for the abundance of pseudo-pilots is obvious: they can easily be interpreted as showing encouragingly positive results for whatever SCAM is being tested. Subsequently, SCAM proponents can mislead the public by claiming that there are plenty of positive studies and therefore their SCAM is supported by sound evidence.

‘SAFE‘ STUDY-DESIGNS

As regularly mentioned on this blog, there are several ways to design a study such that the risk of producing a negative result is minimal. The most popular one in SCAM research is the ‘A+B versus B’ design. In this study, for instance, cancer patients who were suffering from fatigue were randomised to receive usual care or usual care plus regular acupuncture. The researchers then monitored the patients’ experience of fatigue and found that the acupuncture group did better than the control group. The effect was statistically significant, and an editorial in the journal where it was published called this evidence “compelling”. Due to a cleverly over-stated press-release, news spread fast, and the study was celebrated worldwide as a major breakthrough in cancer-care.

Imagine you have an amount of money A and your friend owns the same sum plus another amount B. Who has more money? Simple, it is, of course your friend: A+B will always be more than A [unless B is a negative amount]. For the same reason, such “pragmatic” trials will always generate positive results [unless the treatment in question does actual harm]. Treatment as usual plus acupuncture is more than treatment as usual alone, and the former is therefore more than likely to produce a better result. This will be true, even if acupuncture is a pure placebo – after all, a placebo is more than nothing, and the placebo effect will impact on the outcome, particularly if we are dealing with a highly subjective symptom such as fatigue.

A more obvious method for generating false positive results is to omit blinding. The purpose of blinding the patient, the therapist and the evaluator of the group allocation in clinical trials is to make sure that expectation is not a contributor to the result. Expectation might not move mountains, but it can certainly influence the result of a clinical trial. Patients who hope for a cure regularly do get better, even if the therapy they receive is useless, and therapists as well as evaluators of the outcomes tend to view the results through rose-tinted spectacles, if they have preconceived ideas about the experimental treatment.

Failure to randomise is another source of bias which can mislead us. If we allow patients or trialists to select or chose which patients receive the experimental and which get the control-treatment, it is likely that the two groups differ in a number of variables. Some of these variables might, in turn, impact on the outcome. If, for instance, doctors allocate their patients to the experimental and control groups, they might select those who will respond to the former and those who don’t to the latter. This may not happen with intent but through intuition or instinct: responsible health care professionals want those patients who, in their experience, have the best chances to benefit from a given treatment to receive that treatment. Only randomisation can, when done properly, make sure we are comparing comparable groups of patients. Non-randomisation can easily generate false-positive findings.

It is also possible to mislead people with studies which do not test whether an experimental treatment is superior to another one (often called superiority trials), but which assess whether it is equivalent to a therapy that is generally accepted to be effective. The idea is that, if both treatments produce similarly positive results, both must be effective. Such trials are called non-superiority or equivalence trials, and they offer a wide range of possibilities for misleading us. If, for example, such a trial has not enough patients, it might show no difference where, in fact, there is one. Let’s consider a simple, hypothetical example: someone comes up with the idea to compare antibiotics to acupuncture as treatments of bacterial pneumonia in elderly patients. The researchers recruit 10 patients for each group, and the results reveal that, in one group, 2 patients died, while, in the other, the number was 3. The statistical tests show that the difference of just one patient is not statistically significant, and the authors therefore conclude that acupuncture is just as good for bacterial infections as antibiotics.

Even trickier is the option to under-dose the treatment given to the control group in an equivalence trial. In the above example, the investigators might subsequently recruit hundreds of patients in an attempt to overcome the criticism of their first study; they then decide to administer a sub-therapeutic dose of the antibiotic in the control group. The results would then seemingly confirm the researchers’ initial finding, namely that acupuncture is as good as the antibiotic for pneumonia. Acupuncturists might then claim that their treatment has been proven in a very large randomised clinical trial to be effective for treating this condition. People who do not happen to know the correct dose of the antibiotic could easily be fooled into believing them.

Obviously, the results would be more impressive, if the control group in an equivalence trial received a therapy which is not just ineffective but actually harmful. In such a scenario, even the most useless SCAM would appear to be effective simply because it is less harmful than the comparator.

A variation of this theme is the plethora of controlled clinical trials in SCAM which compare one unproven therapy to another unproven treatment. Perdicatbly, the results would often indicate that there is no difference in the clinical outcome experienced by the patients in the two groups. Enthusiastic SCAM researchers then tend to conclude that this proves both treatments to be equally effective. The more likely conclusion, however, is that both are equally useless.

Another technique for misleading the public is to draw conclusions which are not supported by the data. Imagine you have generated squarely negative data with a trial of homeopathy. As an enthusiast of homeopathy, you are far from happy with your own findings; in addition you might have a sponsor who puts pressure on you. What can you do? The solution is simple: you only need to highlight at least one positive message in the published article. In the case of homeopathy, you could, for instance, make a major issue about the fact that the treatment was remarkably safe and cheap: not a single patient died, most were very pleased with the treatment which was not even very expensive.

OMISSION

A further popular method for misleading the public is the outright omission findings that SCAM researchers do not like. If the aim is that the public believe the myth that all SCAM is free of side-effects, SCAM researchers only need to omit reporting them in clinical trials. On this blog, I have alerted my readers time and time again to this common phenomenon. We even assessed it in a systematic review. Sixty RCTs of chiropractic were included. Twenty-nine RCTs did not mention adverse effects at all. Sixteen RCTs reported that no adverse effects had occurred. Complete information on incidence, severity, duration, frequency and method of reporting of adverse effects was included in only one RCT.

Most trails have many outcome measures; for instance, a study of acupuncture for pain-control might quantify pain in half a dozen different ways, it might also measure the length of the treatment until pain has subsided, the amount of medication the patients took in addition to receiving acupuncture, the days off work because of pain, the partner’s impression of the patient’s health status, the quality of life of the patient, the frequency of sleep being disrupted by pain etc. If the researchers then evaluate all the results, they are likely to find that one or two of them have changed in the direction they wanted (especially, if they also include half a dozen different time points at which these variables are quatified). This can well be a chance finding: with the typical statistical tests, one in 20 outcome measures would produce a significant result purely by chance. In order to mislead us, the researchers only need to “forget” about all the negative results and focus their publication on the ones which by chance have come out as they had hoped.

FRAUD

When it come to fraud, there is more to chose from than one would have ever wished for. We and others have, for example, shown that Chinese trials of acupuncture hardly ever produce a negative finding. In other words, one does not need to read the paper, one already knows that it is positive – even more extreme: one does not need to conduct the study, one already knows the result before the research has started. This strange phenomenon indicates that something is amiss with Chinese acupuncture research. This suspicion was even confirmed by a team of Chinese scientists. In this systematic review, all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of acupuncture published in Chinese journals were identified by a team of Chinese scientists. A total of 840 RCTs were found, including 727 RCTs comparing acupuncture with conventional treatment, 51 RCTs with no treatment controls, and 62 RCTs with sham-acupuncture controls. Among theses 840 RCTs, 838 studies (99.8%) reported positive results from primary outcomes and two trials (0.2%) reported negative results. The percentages of RCTs concealment of the information on withdraws or sample size calculations were 43.7%, 5.9%, 4.9%, 9.9%, and 1.7% respectively. The authors concluded that publication bias might be major issue in RCTs on acupuncture published in Chinese journals reported, which is related to high risk of bias. We suggest that all trials should be prospectively registered in international trial registry in future.

A survey of clinical trials in China has revealed fraudulent practice on a massive scale. China’s food and drug regulator carried out a one-year review of clinical trials. They concluded that more than 80 percent of clinical data is “fabricated“. The review evaluated data from 1,622 clinical trial programs of new pharmaceutical drugs awaiting regulator approval for mass production. Officials are now warning that further evidence malpractice could still emerge in the scandal.

I hasten to add that fraud in SCAM research is certainly not confined to China. On this blog, you will find plenty of evidence for this statement, I am sure.

CONCLUSION

Research is obviously necessary, if we want to answer the many open questions in SCAM. But sadly, not all research is reliable and much of SCAM research is misleading. Therefore, it is always necessary to be on the alert and apply all the skills of critical evaluation we can muster.

At present, we see a wave of promotion of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as a treatment of corona-virus infections. In this context, we should perhaps bear in mind that much of the Chinese data seem to be less than reliable. Moreover, I find it important to alert people to a stern warning recently published by two Australian experts. Here is the crucial passage from their paper:

We wish to highlight significant concerns regarding the association between traditional herbal medicines and severe, non-infective interstitial pneumonitis and other aggressive pulmonary syndromes, such as diffuse alveolar haemorrhage and ARDS which have emerged from Chinese and Japanese studies particularly during the period 2017−2019. Initially the association between traditional herbal therapies and pneumonitis was based on isolated case reports. These included hypersensitivity pneumonitis associated with the use of traditional Chinese or Japanese medicines such as Sai-rei-to, Oren-gedoku-to, Seisin-renshi-in and Otsu-ji-to (9 references in supplemental file). Larger cohorts and greater numbers now support this crucial relationship. In a Japanese cohort of 73 patients, pneumonitis development occurred within 3 months of commencing traditional medicine in the majority of patients [3], while a large report from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, described more than 1000 cases of lung injury secondary to traditional medications, the overwhelming majority of which (852 reports) were described as ‘interstitial lung disease [4].

Currently the constituent of traditional herbal medicines which is considered most likely to underlie causation of lung disease is Scutellariae Radix also known as Skullcap or ou-gon, which has been implicated through immunological evidence of hypersensitivity as well as circumstantial evidence, being present in all of those medicines outlined above [3]. Notably, skullcap is a constituent of QPD as used and described in the paper by Ren et al. relating to COVID-19 [1]. Scutellariae Radix-induced ARDS and COVID-19 disease share the same characteristic chest CT changes such as ground-glass opacities and airspace consolidation, therefore distinguishing between lung injury due to SARS-CoV-2 and that secondary to TCM may be very challenging. The potential for iatrogenic lung injury with TCM needs to be acknowledged [5]…

Morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 are almost entirely related to lung pathology [6]. Factors which impose a burden on lung function such as chronic lung disease and smoking are associated with increased risk for a poor outcome. Severe COVID-19 may be associated with a hypersensitivity pneumonitis component responsive to corticosteroid therapy [7]. Against this background the use of agents with little or no evidence of clinical efficacy and which have been significantly implicated in causing interstitial pneumonitis that could complicate SARS-CoV-2 infection, should be considered with extreme caution.

In conclusion, the benefits of TCM in the treatment of COVID-19 remain unproven and may be potentially deleterious. We recognise that there is currently insufficient evidence to prove the role of TCM in the causation of interstitial pneumonitis, however the circumstantial data is powerful and it would seem prudent to avoid these therapies in patients with known or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection, until the evidence supports their use.

Declaration of Competing Interest: There are no conflicts to declare.

Yesterday, I received a tweet from a guy called Bart Huisman (“teacher beekeeping, nature, biology, classical homeopathy, agriculture, health science, social science”). I don’t know him and cannot remember whether I had previous contact with him. His tweet read as follows:

“Why should anyone believe what Professor Edzard Ernst says, after he put his name to a BBC programme, he now describes as “deception”.”

This refers to a story that I had almost forgotten. It’s a nice one with a ‘happy ending’, so let me recount it here briefly.

In 2005, the BBC had hired me as an advisor for their 4-part TV series on alternative medicine.

The first part of the series was on acupuncture, and Prof Kathy Sykes presented the opening scene taking place in a Chinese operation theatre. In it a Chinese women was having open heart surgery with the aid of acupuncture. Kathy’s was visibly impressed and said on camera that the patient was having the surgery “with only needles to control the pain.” However, the images clearly revealed that the patient was receiving all sorts of other treatments given through intra-venous lines. So, Prof Sykes was telling the UK public a bunch of porkies. This was bound to confuse many viewers.

One of them was Simon Singh. At the time, I did not know Simon (to be honest, I did not even know of him) and was surprised to receive a phone call from him. He politely asked me to confirm that I had been the adviser of the BBC on this production. I was happy to confirm this fact. Then he asked why I had missed such a grave error. I replied that I could not possibly have spotted it, because all I had been asked to do was to review and correct the text of the programme which the BBC had sent to me by email. Before it was broadcast, I had not seen a single passage of the film.

Correcting the text had already led to several problems (not so much regarding the acupuncture part but mostly the other sections), because the BBC was reluctant to change several of the mistakes I had identified. When I told them that, in this case, I would quit, they finally found a way to alter them. But the cooperation had been far from easy. I explained all this to Simon and eventually he asked me whether I would be willing to support the official complaint he was about to file with the BBC. I agreed. This is probably where I used the term ‘deception’ that Mr Huisman mentioned in his tweet.

So, Simon submitted his complaint and eventually won the case.

But this is not the happy ending I was referring to.

During the course of the complaint, Simon and I realised that we were thinking alike and were getting on well. A few months later, he suggested that the two of us write a book together about alternative medicine. At first, I was hesitant. Simon said, “let’s try just one chapter, and see how it works out.” So we did. It turned out to be fun and instructive for both of us. So we did the other chapters as well. The book was published in 2008 and is called TRICK OR TREATMENT. It was published in about 20 different languages and the German version became ‘science book of the year in 2011 (I think).

And that’s not the happy ending either (in fact, it caused a lot of hardship for Simon who was sued by the BCA; luckily, he won that case too).

The real happy ending is the fact that Simon and I became friends for life.

Thank you Bart Huisman for reminding me of this rather lovely story.

By guest blogger Loretta Marron

If scientists were fearful of a clinical trial’s producing negative results, would they even pursue it? A draft Chinese regulation issued in late May aims to criminalise individual scientists and organisations whom China claims damage the reputation of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

Beijing has a reputation for reprimanding those who decry TCM. Such criticism is blocked on Chinese Internet. Silencing doctors is becoming the norm.

In January 2018, former anaesthetist, Tan Qindong, was arrested and spent more than three months in detention after criticising a widely advertised, best-selling ‘medicinal’ TCM liquor. Claiming that it was a ‘poison’, he believed that he was protecting the elderly and vulnerable patients with high blood pressure. Police claimed that a post on social media damaged the reputation of the TCM ‘liquor’ and of the company making it. Shortly after release, he suffered post-traumatic stress and was hospitalised.

On 30 December 2019, Chinese ophthalmologist, the late Dr Li Wenliang, was one of the first to recognise the outbreak of COVD-19. He posted a private warning to a group of fellow doctors about a possible outbreak of an illness resembling severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). He encouraged them to protect themselves from infection. Days later, after his post when viral, he was summoned to the Public Security Bureau in Wuhan and forced to “admit to lying about the existence of a worrying new virus”. Li was accused of violating the provisions of the “People’s Republic of China Public Order Management and Punishment Law” for spreading “unlawful spreading of untruthful topics on the internet” and of disturbing the social order. He was made to sign a statement that he would “halt this unlawful behaviour”.

In April 2020, Chinese physician Yu Xiangdong, a senior medico who worked on the front line battling COVID-19, posted on Weibo, a Twitter-like site, a criticism of the use of antibiotics and TCM to treat COVID-19. He was demoted from his positions as assistant dean at the Central Hospital in the central city of Huangshi and director of quality management for the city’s Edong Healthcare Group. Well known for promoting modern medicine amongst the Chinese, Yu had almost a million followers on social media. All his postings vanished.

Beijing insists that TCM has been playing a crucial role in COVID-19 prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. Claims continue to be made for “effective TCM recipes”. However, no randomised clinical trial has been published in any reputable journal.

TCM needs proper scrutiny, but criticising it could land you years in prison. If the benefits of suggested herbal remedies are to be realised, good clinical studies must be encouraged. For TCM, this might never be permitted.

Don’t think for a moment that you are safe in Australia.

Article 8.25 of the Free Trade Agreement Between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People’s Republic of China reads:

Traditional Chinese Medicine Services (“TCM”)

- Within the relevant committees to be established in accordance with this Agreement, and subject to available resources, Australia and China shall cooperate on matters relating to trade in TCM services.

- Cooperation identified in paragraph 2 shall:

(a) include exchanging information, where appropriate, and discussing policies, regulations and actions related to TCM services; and

(b) encourage future collaboration between regulators, registration authorities and relevant professional bodies of the Parties to facilitate trade in TCM and complementary medicines, in a manner consistent with all relevant regulatory frameworks. Such collaboration, involving the competent authorities of both Parties – for Australia, notably the Department of Health, and for China the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine – will foster concrete cooperation and exchanges relating to TCM.

By guest blogger Loretta Marron

Although assumed to be traditional, what we know today as ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine’ (TCM) was invented in the 1950s for political reasons by then Chairman Mao. It has since been proclaimed by Xi Jinping, now life-President of the People’s Republic of China, as the “jewel” in the millennia of Chinese civilization.

In May this year, Xi “announced plans to criminalise criticism of traditional Chinese medicine”. Speaking out against TCM could land you years in prison, prosecuted for “picking fights to disturb public order” and “defaming” the practice.

With the industry expected to earn $420 billion by the end of 2020, covid-19 has provided Xi with a platform to promote unproven, potentially harmful TCM. To keep these profits filling Chinese coffers, the World Health Organization (WHO) remains silent and those challenging TCM are silenced.

In January, the late Dr Li Wenliang was arrested and gaoled for warning China about covid-19. Li was one of up to nine people who were disciplined for spreading rumours about it. As the virus silently spread around the world, Beijing told the WHO that there was ‘no clear evidence’ of spread between humans.

As their death toll passed 1,000, Beijing’s response was to remove senior officials and to sack hundreds over their handling of the outbreak. With the support of the WHO, claims continue to be made that TCM “has been proved effective in improving the cure rate”, denying the simple fact that “patients would have recovered even if they hadn’t taken the Chinese medicine”.

With cases now heading for 8 million, and over four hundred thousand people confirmed dead world-wide and with economies in free-fall, Beijing continues, “to protect its interests and people overseas; to gain leadership of international governance”,for financial gain, to aggressively use its national power. Under the guise of ‘International Aid’, during the pandemic, Beijing promoted treatments based on unproven traditional medicine, sending TCM practitioners to countries including Italy, France and Iran.

Countries challenging Beijing can expect claims of racism and financial retaliation.

Back in 2016, the Chinese State Council released a “Strategic Development Plan for Chinese Medicine (2016-2030)”, seeking to spread ‘knowledge’ into campuses, homes and abroad.

In July 2017, a law promising equal status for TCM and western medicine came into effect. Provisions included encouragement to China’s hospitals to set up TCM centres. “The new law on traditional Chinese medicine will improve global TCM influence, and give a boost to China’s soft power”.

In 2019, after strong lobbying by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), WHO added a chapter on TCM to their official International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). In China, doctors are now instructed to prescribe traditional medicine to most patients.

While Chinese herbs might have exotic names, they are, once translated, often the same as western herbs, many of which might have significant interactions. WHO fails to acknowledge any drug interactions.

In 1967, Mao launched Project 523 to find a cure for chloroquine-resistant malaria. Over 240,000 compounds had already been tested and none had worked. Trained in pharmacology and modern western methods, Tu Youyou used the scientific method to test sweet wormwood, a herb traditionally used in China for fever, where she developed a useful artemisinin derivative for resistant malaria. The drug has saved millions of lives. In 2015 she won the Nobel Prize for her work. However, Tu’s work is not a blanket endorsement of TCM: without the years of research, she would not have been successful.

TCM is commercially driven. Criticism of remedies is often blocked on the Internet in China, and critics have been jailed. The majority of TCM’s are not tested for efficacy in randomized clinical trials. Clinical trials are usually of poor quality and serious side effects are underreported. China has even rolled back regulations as Beijing forcefully promotes TCM’s as an alternative to proven western medicine. An increasing number of prestigious research hospitals now prescribe and dispense herbs that may cause drug interactions alongside western medicine for major illness patients.

TCM’s are not safe. Most systematic reviews suggest that there is no good or consistent evidence for effectiveness, negative results aren’t published, research data are fabricated and TCM-exports are of dubious quality.

If the benefits of herbal remedies are to be realised, good clinical studies must be encouraged.

TCM is not medicine. It’s little more than a philosophy or a set of traditional beliefs, about various concoctions and interventions and their alleged effect on health and diseases.

To stop misleading the world with what Mao himself saw as nonsense, and to mitigate future pandemics, WHO can and should remove all mention of TCM other than to state that it is unproven and could be dangerous.