bias

Some homeopaths claim that there is anecdotal support for the use of the homeopathic medicine Arsenicum album in preventing post-vaccination fever. As far as I know, the claim has not been tested in clinical trials. This study was aimed at evaluating the efficacy of this approach in preventing febrile episodes following vaccination.

In the community medicine out-patient of Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, West Bengal, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted on 120 children. All of them presented for the 2nd and 3rd dose of DPT-HepB-Polio vaccination and reported febrile episodes following the 1st dose. They were treated with Arsenicum album 30cH 6 doses or placebo (indistinguishable from verum), thrice daily for two subsequent days. Parents were advised to report any event of febrile attacks within 48h of vaccination.

The groups were comparable at baseline. Children reporting fever after the 2nd dose was 29.8% and 30.4% respectively for the homeopathy group and control group respectively [Relative Risk (RR)=1.008] with no significant difference (P=0.951) between groups. After the 3rd dose, children reporting fever were 31.5% and 28.3% respectively for the homeopathy group and control group respectively (RR=0.956) with no significant difference (P=0.719) between groups.

The authors concluded that empirically selected Arsenicum album 30cH could not produce differentiable effect from placebo in preventing febrile episodes following DPT-HepB-Polio vaccination.

I can hear it now, the chorus of homeopaths:

- this is part of a conspiracy against homeopathy,

- the authors of this study display an anti-homeopathy bias,

- this study did not closely follow the principles of homeopathy,

- it lacked the input by experience homeopaths,

- no homeopath worth his money would use Arsenicum album 30cH for this purpose,

- no homeopath in his right mind would employ 6 doses thrice daily for two subsequent days,

- etc., etc.

Well guys, I have to disappoint you: the authors of this paper have the following affiliations:

- Dept. of Pathology and Microbiology, Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal

- Dept. of Community Medicine, Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal

- Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Govt. of West Bengal

- National Institute of Homoeopathy, Ministry of AYUSH, Govt. of India

- Central Council of Homoeopathy, Vill, Champsara

So, perhaps it’s true: highly diluted homeopathic remedies are pure placebos.

In previous posts, I have been scathing about chiropractors (DCs) treating children; for instance here:

- Despite calling themselves ‘doctors’, they are nothing of the sort.

- DCs are not adequately educated or trained to treat children.

- They nevertheless often do so, presumably because this constitutes a significant part of their income.

- Even if they felt confident to be adequately trained, we need to remember that their therapeutic repertoire is wholly useless for treating sick children effectively and responsibly.

- Therefore, harm to children is almost inevitable.

- To this, we must add the risk of incompetent advice from DCs – just think of immunisations.

Now we have more data on this subject. This new study investigated the effectiveness of adding manipulative therapy to other conservative care for spinal pain in a school-based cohort of Danish children aged 9–15 years.

The design was a two-arm pragmatic randomised controlled trial, nested in a longitudinal open cohort study in Danish public schools. 238 children from 13 public schools were included. A text message system and clinical examinations were used for data collection. Interventions included either (1) advice, exercises and soft-tissue treatment or (2) advice, exercises and soft-tissue treatment plus manipulative therapy. The primary outcome was number of recurrences of spinal pain. Secondary outcomes were duration of spinal pain, change in pain intensity and Global Perceived Effect.

No significant difference was found between groups in the primary outcomes of the control group and intervention group. Children in the group receiving manipulative therapy reported a higher Global Perceived Effect. No adverse events were reported.

The authors – well-known proponents of chiropractic (who declared no conflicts of interest) – concluded that adding manipulative therapy to other conservative care in school children with spinal pain did not result in fewer recurrent episodes. The choice of treatment—if any—for spinal pain in children therefore relies on personal preferences, and could include conservative care with and without manipulative therapy. Participants in this trial may differ from a normal care-seeking population.

The study seems fine, but what a conclusion!!!

After demonstrating that chiropractic manipulation is useless, the authors state that the treatment of kids with back pain could include conservative care with and without manipulative therapy. This is more than a little odd, in my view, and seems to suggest that chiropractors live on a different planet from those of us who can think rationally.

Psoriasis is one of those conditions that is

- chronic,

- not curable,

- irritating to the point where it reduces quality of life.

In other words, it is a disease for which virtually all alternative treatments on the planet are claimed to be effective. But which therapies do demonstrably alleviate the symptoms?

This review (published in JAMA Dermatology) compiled the evidence on the efficacy of the most studied complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities for treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis and discusses those therapies with the most robust available evidence.

PubMed, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov searches (1950-2017) were used to identify all documented CAM psoriasis interventions in the literature. The criteria were further refined to focus on those treatments identified in the first step that had the highest level of evidence for plaque psoriasis with more than one randomized clinical trial (RCT) supporting their use. This excluded therapies lacking RCT data or showing consistent inefficacy.

A total of 457 articles were found, of which 107 articles were retrieved for closer examination. Of those articles, 54 were excluded because the CAM therapy did not have more than 1 RCT on the subject or showed consistent lack of efficacy. An additional 7 articles were found using references of the included studies, resulting in a total of 44 RCTs (17 double-blind, 13 single-blind, and 14 nonblind), 10 uncontrolled trials, 2 open-label nonrandomized controlled trials, 1 prospective controlled trial, and 3 meta-analyses.

Compared with placebo, application of topical indigo naturalis, studied in 5 RCTs with 215 participants, showed significant improvements in the treatment of psoriasis. Treatment with curcumin, examined in 3 RCTs (with a total of 118 participants), 1 nonrandomized controlled study, and 1 uncontrolled study, conferred statistically and clinically significant improvements in psoriasis plaques. Fish oil treatment was evaluated in 20 studies (12 RCTs, 1 open-label nonrandomized controlled trial, and 7 uncontrolled studies); most of the RCTs showed no significant improvement in psoriasis, whereas most of the uncontrolled studies showed benefit when fish oil was used daily. Meditation and guided imagery therapies were studied in 3 single-blind RCTs (with a total of 112 patients) and showed modest efficacy in treatment of psoriasis. One meta-analysis of 13 RCTs examined the association of acupuncture with improvement in psoriasis and showed significant improvement with acupuncture compared with placebo.

The authors concluded that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis are indigo naturalis, curcumin, dietary modification, fish oil, meditation, and acupuncture. This review will aid practitioners in advising patients seeking unconventional approaches for treatment of psoriasis.

I am sorry to say so, but this review smells fishy! And not just because of the fish oil. But the fish oil data are a good case in point: the authors found 12 RCTs of fish oil. These details are provided by the review authors in relation to oral fish oil trials: Two double-blind RCTs (one of which evaluated EPA, 1.8g, and DHA, 1.2g, consumed daily for 12 weeks, and the other evaluated EPA, 3.6g, and DHA, 2.4g, consumed daily for 15 weeks) found evidence supporting the use of oral fish oil. One open-label RCT and 1 open-label non-randomized controlled trial also showed statistically significant benefit. Seven other RCTs found lack of efficacy for daily EPA (216mgto5.4g)or DHA (132mgto3.6g) treatment. The remainder of the data supporting efficacy of oral fish oil treatment were based on uncontrolled trials, of which 6 of the 7 studies found significant benefit of oral fish oil. This seems to support their conclusion. However, the authors also state that fish oil was not shown to be effective at several examined doses and duration. Confused? Yes, me too!

Even more confusing is their failure to mention a single trial of Mahonia aquifolium. A 2013 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Dermatology included 5 RCTs of Mahonia aquifolium which, according to these authors, provided ‘limited support’ for its effectiveness. How could they miss that?

More importantly, how could the reviewers miss to conduct a proper evaluation of the quality of the studies they included in their review (even in their abstract, they twice speak of ‘robust evidence’ – but how can they without assessing its robustness? [quantity is not remotely the same as quality!!!]). Without a transparent evaluation of the rigour of the primary studies, any review is nearly worthless.

Take the 12 acupuncture trials, for instance, which the review authors included based not on an assessment of the studies but on a dodgy review published in a dodgy journal. Had they critically assessed the quality of the primary studies, they could have not stated that CAM therapies with the most robust evidence of efficacy for treatment of psoriasis …[include]… acupuncture. Instead they would have had to admit that these studies are too dubious for any firm conclusion. Had they even bothered to read them, they would have found that many are in Chinese (which would have meant they had to be excluded in their review [as many pseudo-systematic reviewers, the authors only considered English papers]).

There might be a lesson in all this – well, actually I can think of at least two:

- Systematic reviews might well be the ‘Rolls Royce’ of clinical evidence. But even a Rolls Royce needs to be assembled correctly, otherwise it is just a heap of useless material.

- Even top journals do occasionally publish poor-quality and thus misleading reviews.

I have often cautioned my readers about the ‘evidence’ supporting acupuncture (and other alternative therapies). Rightly so, I think. Here is yet another warning.

This systematic review assessed the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of postpartum depression (PPD). Nine trials involving 653 women were selected. A meta-analysis demonstrated that the acupuncture group had a significantly greater overall effective rate compared with the control group. Moreover, acupuncture significantly increased oestradiol levels compared with the control group. Regarding the HAMD and EPDS scores, no difference was found between the two groups. The Chinese authors concluded that acupuncture appears to be effective for postpartum depression with respect to certain outcomes. However, the evidence thus far is inconclusive. Further high-quality RCTs following standardised guidelines with a low risk of bias are needed to confirm the effectiveness of acupuncture for postpartum depression.

What a conclusion!

What a review!

What a journal!

What evidence!

Let’s start with the conclusion: if the authors feel that the evidence is ‘inconclusive’, why do they state that ‘acupuncture appears to be effective for postpartum depression‘. To me this does simply not make sense!

Such oddities are abundant in the review. The abstract does not mention the fact that all trials were from China (published in Chinese which means that people who cannot read Chinese are unable to check any of the reported findings), and their majority was of very poor quality – two good reasons to discard the lot without further ado and conclude that there is no reliable evidence at all.

The authors also tell us very little about the treatments used in the control groups. In the paper, they state that “the control group needed to have received a placebo or any type of herb, drug and psychological intervention”. But was acupuncture better than all or any of these treatments? I could not find sufficient data in the paper to answer this question.

Moreover, only three trials seem to have bothered to mention adverse effects. Thus the majority of the studies were in breach of research ethics. No mention is made of this in the discussion.

In the paper, the authors re-state that “this meta-analysis showed that the acupuncture group had a significantly greater overall effective rate compared with the control group. Moreover, acupuncture significantly increased oestradiol levels compared with the control group.” This is, I think, highly misleading (see above).

Finally, let’s have a quick look at the journal ‘Acupuncture in Medicine’ (AiM). Even though it is published by the BMJ group (the reason for this phenomenon can be found here: “AiM is owned by the British Medical Acupuncture Society and published by BMJ”; this means that all BMAS-members automatically receive the journal which thus is a resounding commercial success), it is little more than a cult-newsletter. The editorial board is full of acupuncture enthusiasts, and the journal hardly ever publishes anything that is remotely critical of the wonderous myths of acupuncture.

My conclusion considering all this is as follows: we ought to be very careful before accepting any ‘evidence’ that is currently being published about the benefits of acupuncture, even if it superficially looks ok. More often than not, it turns out to be profoundly misleading, utterly useless and potentially harmful pseudo-evidence.

Reference

Acupunct Med. 2018 Jun 15. pii: acupmed-2017-011530. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2017-011530. [Epub ahead of print]

Effectiveness of acupuncture in postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Li S, Zhong W, Peng W, Jiang G.

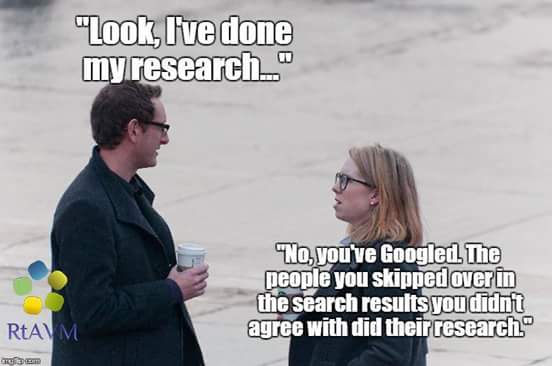

How often do we hear this sentence: “I know, because I have done my research!” I don’t doubt that most people who make this claim believe it to be true.

But is it?

What many mean by saying, “I know, because I have done my research”, is that they went on the internet and looked at a few websites. Others might have been more thorough and read books and perhaps even some original papers. But does that justify their claim, “I know, because I have done my research”?

The thing is, there is research and there is research.

The dictionary defines research as “The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions.” This definition is helpful because it mentions several issues which, I believe, are important.

Research should be:

- systematic,

- an investigation,

- establish facts,

- reach new conclusions.

To me, this indicates that none of the following can be truly called research:

- looking at a few randomly chosen papers,

- merely reading material published by others,

- uncritically adopting the views of others,

- repeating the conclusions of others.

Obviously, I am being very harsh and uncompromising here. Not many people could, according to these principles, truthfully claim to have done research in alternative medicine. Most people in this realm do not fulfil any of those criteria.

As I said, there is research and research – research that meets the above criteria, and the type of research most people mean when they claim: “I know, because I have done my research.”

Personally, I don’t mind that the term ‘research’ is used in more than one way:

- there is research meeting the criteria of the strict definition

- and there is a common usage of the word.

But what I do mind, however, is when the real research is claimed to be as relevant and reliable as the common usage of the term. This would be a classical false equivalence, akin to putting experts on a par with pseudo-experts, to believing that facts are no different from fantasy, or to assume that truth is akin to post-truth.

Sadly, in the realm of alternative medicine (and alarmingly, in other areas as well), this is exactly what has happened since quite some time. No doubt, this might be one reason why many consumers are so confused and often make wrong, sometimes dangerous therapeutic decisions. And this is why I think it is important to point out the difference between research and research.

They say that minds are like parachutes – they function only when open. Having an open mind means being receptive to new and different ideas or the opinions of others.

I am regularly accused of lacking this quality. Most recently, an acupuncturist questioned whether acupuncture-sceptics, and I in particular, have an open mind. Subsequently, an interesting dialogue ensued:

___________________________________________________________

Tom Kennedy on Wednesday 01 August 2018 at 19:27

the EVIDENCEBASEDACUPUNCTURE site you recommend quotes the Vickers meta-analysis thus:

“A meta-analysis of 17,922 patients from randomized trials concluded, “Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo.”

Pity that they forgot a bit. The full conclusion reads:

“Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo. However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture.”

AND YOU TRY TO LECTURE US ABOUT AN OPEN MIND?

@Edzard I’m not sure I understand your point. ‘However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture.’ Perhaps the full conclusion should always be quoted, but I don’t think that addendum changes the context significantly. Acupuncture has been shown to be more than a placebo in a large meta-analysis (when compared to arguably active sham controls). The authors put it well I think, in the ‘Interpretation’ section:

‘Our finding that acupuncture has effects over and above sham acupuncture is therefore of major importance for clinical practice. Even though on average these effects are small, the clinical decision made by doctors and patients is not between true and sham acupuncture, but between a referral to an acupuncturist or avoiding such a referral. The total effects of acupuncture, as experienced by the patient in routine practice, include both the specific effects associated with correct needle insertion according to acupuncture theory, non-specific physiologic effects of needling, and non-specific psychological (placebo) effects related to the patient’s belief that treatment will be effective.’

Compare this to Richard’s comment here, for example: ‘Of course the effects of ‘acupuncture’ (if any) are due to placebo responses (and perhaps nocebo responses in some cases). What else?’. And your post tile includes the line ‘the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo’. These are the kinds of comment that to me seem closed-minded in the face of some significant evidence.

edzard on Thursday 02 August 2018 at 12:46

“Perhaps the full conclusion should always be quoted…”

YES, IF NOT, IT’S CALLED ‘BEING ECONOMICAL WITH THE TRUTH’

“…I don’t think that addendum changes the context significantly.”

IT’S NOT AN ADDENDUM, BUT PART OF THE CONCLUSION; AND YOU ARE WRONG, FOR ME, IT CHANGES A LOT.

“…your post tile includes the line ‘the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo’.”

BECAUSE THIS IS WHAT THE PAPER DISCUSSED IN THAT PARTICULAR POST IMPLIED.

‘IT’S CALLED ‘BEING ECONOMICAL WITH THE TRUTH’’

The title of this post is: ‘Yet another confirmation: the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo’. That’s also being economical with the truth I think. You argue ‘BECAUSE THIS IS WHAT THE PAPER DISCUSSED IN THAT PARTICULAR POST IMPLIED’, but is it? The authors state ‘Future studies are needed to confirm or refute any effects of acupuncture in acute stroke’, and that would have been a much more balanced headline. You clearly imply here that it has been CONFIRMED that the effects of acupuncture are due to placebo, and that this trial is further confirmation. This is misleading at best. Yes, you add in brackets ‘(for acute stroke)’ at the end of the post, but why not in the title, unless you want to give the impression this is true for acupuncture in general

Edzard on Thursday 02 August 2018 at 14:09

my post is about critical evaluation of the published literature.

and this is what follows from a critical evaluation of this particular article.

I am not surprised that you cannot follow this line of reasoning.

could it be that the lack of an open mind is not my but your problem

‘could it be that the lack of an open mind is not my but your problem?’

Who knows, maybe the problem is both of ours? I’m open to all possibilities!

VERY GOOD!

ok, let’s have a look.

you 1st: learnt acupuncture [a therapy that relies on a 2000 year old dogma], never published anything negative about it, never used any other therapeutic modality, even treated my own daughter with acupuncture when she suffered from infant colic, earn my livelihood by doing acupuncture.

[I MIGHT BE WRONG HERE, AS I DON’T KNOW ALL THAT MUCH ABOUT YOU, SO PLEASE CORRECT ME]

me next: studied acupuncture during my time in med school, used it occasionally, learnt to use dozens of other therapeutic modalities, published lots about acupuncture based on the current evidence [this means that some conclusions – even of my Cochrane reviews – were positive but have since changed], worked with acupuncturists from across the globe, published one book about acupuncture together with several acupuncture fans, now dedicate my time to the critical analysis of the literature and bogus claims, have no conflicts of interest.

[IN CASE YOU KNOW MORE RELEVANT THINGS ABOUT ME, PLEASE ADD]

@Edzard Your summaries seem to be more or less accurate. However, a) I wouldn’t agree with your use of the term ‘dogma’; b) I haven’t published any scientific papers, but I’ve acknowledged various problems in the acupuncture field through informal pieces; c) I’ve used other CAM modalities, and I’ve directly or indirectly experienced many conventional modalities; d) I only earn part of my livelihood by doing acupuncture. Yes, my background makes it more likely that I’ll be biased in favour of acupuncture. But your credentials in no way guarantee open-mindedness on the subject, and personally I don’t see that displayed often on this blog. It still makes for interesting and stimulating reading though.

what problems in the acupuncture field have you acknowledged through informal pieces?

can you provide links?

I want to get a feel for the openness of your mind.

“…your credentials in no way guarantee open-mindedness on the subject, and personally I don’t see that displayed often on this blog.”

1) you seem to forget that blog-posts are not scientific papers, not even close.

2) you also forget that my blog is dedicated to the CRITICAL assessment of alt med.

finally, what would make you think that someone has an open mind towards acupuncture, if not the fact that someone has a track record of publishing positive conclusions about it when the evidence allows?

remember: an open mind should not be so open that your brain falls out!

Tom Kennedy on Friday 03 August 2018 at 11:20

Here’s one example: https://www.tomtheacupuncturist.com/blog/2017/2/24/does-acupuncture-really-work

‘what would make you think that someone has an open mind towards acupuncture, if not the fact that someone has a track record of publishing positive conclusions about it when the evidence allows?’

I think there’s plenty of evidence that allows for positive conclusions about acupuncture, but you don’t report these. I understand the slant of this blog, but I’d say it comes across as ‘negative assessment’ rather than ‘critical assessment’. Perhaps you’ll argue that your critical assessment has led you to a negative assessment? I’ll just have to disagree that that’s a fair and open-minded summary of the evidence.

Out of interest, can I ask what your acupuncture training involved (hours, theory, clinic time etc.)?

I am sorry to say that I see no critical evaluation in the post you linked to.

” I’d say it comes across as ‘negative assessment’ rather than ‘critical assessment’.

have you noticed that criticism is often experienced as negative to the person(s) it is aimed at?

‘I am sorry to say that I see no critical evaluation in the post you linked to’

I’ll just have to live with that. I feel as though it acknowledges some of the problems in the acupuncture world, in an attempt at balance. I don’t feel your posts aim for balance, but as you said, a blog isn’t a scientific paper so it’s your prerogative to skew things as you see fit

Edzard on Friday 03 August 2018 at 13:18

it seems to me that the ‘screwing things as you see fit’ is your game.

____________________________________________________________________

This exchange shows how easily I can be provoked to get stroppy and even impolite – I do apologise.

But it also made me wonder: how can anyone be sure to have an open mind?

And how can we decide that a person has a closed mind?

We probably all think we are open minded, but are we correct?

I am not at all sure that I know the answer. It obviously depends a lot on the subject. There are subjects where one hardly needs to keep an open mind and some where it might be advisable to have a closed mind:

- the notion that the earth is flat,

- flying carpets,

- iridology,

- reflexology,

- chiropractic subluxation,

- the vital force,

- detox,

- homeopathy.

No doubt, there will be people who even disagree with this short list.

Something that intrigues me – and I am here main ly talking about alternative medicine – is the fact that I often get praised by people who say, “I do appreciate your critical stance on therapy X, but on my treatment Y you are clearly biased and unfairly negative!” To me, it is an indication of a closed mind, if criticism is applauded as long as it does not tackle someone’s own belief system.

On the subject of homeopathy, Prof M Baum and I once published a paper entitled ‘Should we maintain an open mind about homeopathy?’ Its introduction explains the problem quite well, I think:

Once upon a time, doctors had little patience with the claims made for alternative medicines. In recent years the climate has changed dramatically. It is now politically correct to have an open mind about such matters; “the patient knows best” and “it worked for me” seem to be the new mantras. Although this may be a reasonable approach to some of the more plausible aspects of alternative medicine, such as herbal medicine or physical therapies that require manipulation, we believe it cannot apply across the board. Some of these alternatives are based on obsolete or metaphysical concepts of human biology and physiology that have to be described as absurd with proponents who will not subject their interventions to scientific scrutiny or if they do, and are found wanting, suggest that the mere fact of critical evaluation is sufficient to chase the healing process away. These individuals have a conflict of interest more powerful than the requirement for scientific integrity and yet defend themselves by claiming that those wanting to carry out the trials are in the pocket of the pharmaceutical industry and are part of a conspiracy to deny their patients tried and tested palliatives….

END OF QUOTE

And this leads me to try to define 10 criteria indicative for an open mind.

- to be free of conflicts of interest,

- integrity,

- honesty,

- to resist the temptation of applying double standards,

- to have a track record of having changed one’s views in line with the evidence,

- to not cling to overt absurdities,

- to reject conspiracy theories,

- to be able to engage in a meaningful dialogue with people who have different views,

- to avoid fallacious thinking,

- to be willing to learn more on the subject in question.

I would be truly interested to hear, if you have further criteria, or indeed any other thoughts on the subject.

The Royal College of Chiropractors (RCC), a Company Limited by guarantee, was given a royal charter in 2013. It has following objectives:

- to promote the art, science and practice of chiropractic;

- to improve and maintain standards in the practice of chiropractic for the benefit of the public;

- to promote awareness and understanding of chiropractic amongst medical practitioners and other healthcare professionals and the public;

- to educate and train practitioners in the art, science and practice of chiropractic;

- to advance the study of and research in chiropractic.

In a previous post, I pointed out that the RCC may not currently have the expertise and know-how to meet all these aims. To support the RCC in their praiseworthy endeavours, I therefore offered to give one or more evidence-based lectures on these subjects free of charge.

And what was the reaction?

Nothing!

This might be disappointing, but it is not really surprising. Following the loss of almost all chiropractic credibility after the BCA/Simon Singh libel case, the RCC must now be busy focussing on re-inventing the chiropractic profession. A recent article published by RCC seems to confirm this suspicion. It starts by defining chiropractic:

“Chiropractic, as practised in the UK, is not a treatment but a statutorily-regulated healthcare profession.”

Obviously, this definition reflects the wish of this profession to re-invent themselves. D. D. Palmer, who invented chiropractic 120 years ago, would probably not agree with this definition. He wrote in 1897 “CHIROPRACTIC IS A SCIENCE OF HEALING WITHOUT DRUGS”. This is woolly to the extreme, but it makes one thing fairly clear: chiropractic is a therapy and not a profession.

So, why do chiropractors wish to alter this dictum by their founding father? The answer is, I think, clear from the rest of the above RCC-quote: “Chiropractors offer a wide range of interventions including, but not limited to, manual therapy (soft-tissue techniques, mobilisation and spinal manipulation), exercise rehabilitation and self-management advice, and utilise psychologically-informed programmes of care. Chiropractic, like other healthcare professions, is informed by the evidence base and develops accordingly.”

Many chiropractors have finally understood that spinal manipulation, the undisputed hallmark intervention of chiropractors, is not quite what Palmer made it out to be. Thus, they try their utmost to style themselves as back specialists who use all sorts of (mostly physiotherapeutic) therapies in addition to spinal manipulation. This strategy has obvious advantages: as soon as someone points out that spinal manipulations might not do more good than harm, they can claim that manipulations are by no means their only tool. This clever trick renders them immune to such criticism, they hope.

The RCC-document has another section that I find revealing, as it harps back to what we just discussed. It is entitled ‘The evidence base for musculoskeletal care‘. Let me quote it in its entirety:

The evidence base for the care chiropractors provide (Clar et al, 2014) is common to that for physiotherapists and osteopaths in respect of musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions. Thus, like physiotherapists and osteopaths, chiropractors provide care for a wide range of MSK problems, and may advertise that they do so [as determined by the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA)].

Chiropractors are most closely associated with management of low back pain, and the NICE Low Back Pain and Sciatica Guideline ‘NG59’ provides clear recommendations for managing low back pain with or without sciatica, which always includes exercise and may include manual therapy (spinal manipulation, mobilisation or soft tissue techniques such as massage) as part of a treatment package, with or without psychological therapy. Note that NG59 does not specify chiropractic care, physiotherapy care nor osteopathy care for the non-invasive management of low back pain, but explains that: ‘mobilisation and soft tissue techniques are performed by a wide variety of practitioners; whereas spinal manipulation is usually performed by chiropractors or osteopaths, and by doctors or physiotherapists who have undergone additional training in manipulation’ (See NICE NG59, p806).

The Manipulative Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (MACP), recently renamed the Musculoskeletal Association of Chartered Physiotherapists, is recognised as the UK’s specialist manipulative therapy group by the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists, and has approximately 1100 members. The UK statutory Osteopathic Register lists approximately 5300 osteopaths. Thus, collectively, there are approximately twice as many osteopaths and manipulating physiotherapists as there are chiropractors currently practising spinal manipulation in the UK.

END OF QUOTE

To me this sounds almost as though the RCC is saying something like this:

- We are very much like physiotherapists and therefore all the positive evidence for physiotherapy is really also our evidence. So, critics of chiropractic’s lack of sound evidence-base, get lost!

- The new NICE guidelines were a real blow to us, but we now try to spin them such that consumers don’t realise that chiropractic is no longer recommended as a first-line therapy.

- In any case, other professions also occasionally use those questionable spinal manipulations (and they are even more numerous). So, any criticism of spinal manipulation should not be directed at us but at physios and osteopaths.

- We know, of course, that chiropractors treat lots of non-spinal conditions (asthma, bed-wetting, infant colic etc.). Yet we try our very best to hide this fact and pretend that we are all focussed on back pain. This avoids admitting that, for all such conditions, the evidence suggests our manipulations to be worst than useless.

Personally, I find the RCC-strategy very understandable; after all, the RCC has to try to save the bacon for UK chiropractors. Yet, it is nevertheless an attempt at misleading the public about what is really going on. And even, if someone is sufficiently naïve to swallow this spin, one question emerges loud and clear: if chiropractic is just a limited version of physiotherapy, why don’t we simply use physiotherapists for back problems and forget about chiropractors?

(In case the RCC change their mind and want to listen to me elaborating on these themes, my offer for a free lecture still stands!)

Needle acupuncture in small children is controversial, not least because the evidence that it works is negative or weak, and because small children are unable to consent to the treatment. Yet it is recommended by some acupuncturists for infant colic. This, of course, begs the questions:

- Does the best evidence tell us that acupuncture is effective for infant colic?

- Are acupuncturists who recommend acupuncture for this condition responsible and ethical?

This systematic review and a blinding-test validation based on individual patient data from randomised controlled trials was aimed to assess its efficacy for treating infantile colic. Primary end-points were crying time at mid-treatment, at the end of treatment and at a 1-month follow-up. A 30-min mean difference (MD) in crying time between acupuncture and control was predefined as a clinically important difference. Pearson’s chi-squared test and the James and Bang indices were used to test the success of blinding of the outcome assessors [parents].

The investigators included three randomised controlled trials with data from 307 participants. Only one of the included trials obtained a successful blinding of the outcome assessors in both the acupuncture and control groups. The MD in crying time between acupuncture intervention and no acupuncture control was -24.9 min at mid-treatment, -11.4 min at the end of treatment and -11.8 min at the 4-week follow-up. The heterogeneity was negligible in all analyses. The statistically significant result at mid-treatment was lost when excluding the apparently unblinded study in a sensitivity analysis: MD -13.8 min. The registration of crying during treatment suggested more crying during acupuncture.

The authors concluded that percutaneous needle acupuncture treatments should not be recommended for infantile colic on a general basis.

The authors also provide this further comment: “Our blinding test validated IPD meta-analysis of minimal acupuncture treatments of infantile colic did not show clinically relevant effects in pain reduction as estimated by differences in crying time between needle acupuncture intervention and no acupuncture control. Analyses indicated that acupuncture treatment induced crying in many of the children. Caution should therefore be exercised in recommending potentially painful treatments with uncertain efficacy in infants. The studies are few, the analysis is made on small samples of individuals, and conclusions should be considered in this context. With this limitation in mind, our findings do not support the idea that percutaneous needle acupuncture should be recommended for treatment of infantile colic on a general basis.”

So, returning to the two questions that I listed above – what are the answers?

I think they must be:

- No.

- No.

Can I tempt you to run a little (hopefully instructive) thought-experiment with you? It is quite simple: I will tell you about the design of a clinical trial, and you will tell me what the likely outcome of this study would be.

Are you game?

Here we go:

_____________________________________________________________________________

Imagine we conduct a trial of acupuncture for persistent pain (any type of pain really). We want to find out whether acupuncture is more than a placebo when it comes to pain-control. Of course, we want our trial to look as rigorous as possible. So, we design it as a randomised, sham-controlled, partially-blinded study. To be really ‘cutting edge’, our study will not have two but three parallel groups:

1. Standard needle acupuncture administered according to a protocol recommended by a team of expert acupuncturists.

2. Minimally invasive sham-acupuncture employing shallow needle insertion using short needles at non-acupuncture points. Patients in groups 1 and 2 are blinded, i. e. they are not supposed to know whether they receive the sham or real acupuncture.

3. No treatment at all.

We apply the treatments for a sufficiently long time, say 12 weeks. Before we start, after 6 and 12 weeks, we measure our patients’ pain with a validated method. We use sound statistical methods to compare the outcomes between the three groups.

WHAT DO YOU THINK THE RESULT WOULD BE?

You are not sure?

Well, let me give you some hints:

Group 3 is not going to do very well; not only do they receive no therapy at all, but they are also disappointed to have ended up in this group as they joined the study in the hope to get acupuncture. Therefore, they will (claim to) feel a lot of pain.

Group 2 will be pleased to receive some treatment. However, during the course of the 6 weeks, they will get more and more suspicious. As they were told during the process of obtaining informed consent that the trial entails treating some patients with a sham/placebo, they are bound to ask themselves whether they ended up in this group. They will see the short needles and the shallow needling, and a percentage of patients from this group will doubtlessly suspect that they are getting the sham treatment. The doubters will not show a powerful placebo response. Therefore, the average pain scores in this group will decrease – but only a little.

Group 1 will also be pleased to receive some treatment. As the therapists cannot be blinded, they will do their best to meet the high expectations of their patients. Consequently, they will benefit fully from the placebo effect of the intervention and the pain score of this group will decrease significantly.

So, now we can surely predict the most likely result of this trial without even conducting it. Assuming that acupuncture is a placebo-therapy, as many people do, we now see that group 3 will suffer the most pain. In comparison, groups 1 and 2 will show better outcomes.

Of course, the main question is, how do groups 1 and 2 compare to each other? After all, we designed our sham-controlled trial in order to answer exactly this issue: is acupuncture more than a placebo? As pointed out above, some patients in group 2 would have become suspicious and therefore would not have experienced the full placebo-response. This means that, provided the sample sizes are sufficiently large, there should be a significant difference between these two groups favouring real acupuncture over sham. In other words, our trial will conclude that acupuncture is better than placebo, even if acupuncture is a placebo.

THANK YOU FOR DOING THIS THOUGHT EXPERIMENT WITH ME.

Now I can tell you that it has a very real basis. The leading medical journal, JAMA, just published such a study and, to make matters worse, the trial was even sponsored by one of the most prestigious funding agencies: the NIH.

Here is the abstract:

___________________________________________________________________________

Musculoskeletal symptoms are the most common adverse effects of aromatase inhibitors and often result in therapy discontinuation. Small studies suggest that acupuncture may decrease aromatase inhibitor-related joint symptoms.

Objective:

To determine the effect of acupuncture in reducing aromatase inhibitor-related joint pain.

Design, Setting, and Patients:

Randomized clinical trial conducted at 11 academic centers and clinical sites in the United States from March 2012 to February 2017 (final date of follow-up, September 5, 2017). Eligible patients were postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer who were taking an aromatase inhibitor and scored at least 3 on the Brief Pain Inventory Worst Pain (BPI-WP) item (score range, 0-10; higher scores indicate greater pain).

Interventions:

Patients were randomized 2:1:1 to the true acupuncture (n = 110), sham acupuncture (n = 59), or waitlist control (n = 57) group. True acupuncture and sham acupuncture protocols consisted of 12 acupuncture sessions over 6 weeks (2 sessions per week), followed by 1 session per week for 6 weeks. The waitlist control group did not receive any intervention. All participants were offered 10 acupuncture sessions to be used between weeks 24 and 52.

Main Outcomes and Measures:

The primary end point was the 6-week BPI-WP score. Mean 6-week BPI-WP scores were compared by study group using linear regression, adjusted for baseline pain and stratification factors (clinically meaningful difference specified as 2 points).

Results:

Among 226 randomized patients (mean [SD] age, 60.7 [8.6] years; 88% white; mean [SD] baseline BPI-WP score, 6.6 [1.5]), 206 (91.1%) completed the trial. From baseline to 6 weeks, the mean observed BPI-WP score decreased by 2.05 points (reduced pain) in the true acupuncture group, by 1.07 points in the sham acupuncture group, and by 0.99 points in the waitlist control group. The adjusted difference for true acupuncture vs sham acupuncture was 0.92 points (95% CI, 0.20-1.65; P = .01) and for true acupuncture vs waitlist control was 0.96 points (95% CI, 0.24-1.67; P = .01). Patients in the true acupuncture group experienced more grade 1 bruising compared with patients in the sham acupuncture group (47% vs 25%; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance:

Among postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer and aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgias, true acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture or with waitlist control resulted in a statistically significant reduction in joint pain at 6 weeks, although the observed improvement was of uncertain clinical importance.

__________________________________________________________________________

Do you see how easy it is to deceive (almost) everyone with a trial that looks rigorous to (almost) everyone?

My lesson from all this is as follows: whether consciously or unconsciously, SCAM-researchers often build into their trials more or less well-hidden little loopholes that ensure they generate a positive outcome. Thus even a placebo can appear to be effective. They are true masters of producing false-positive findings which later become part of a meta-analysis which is, of course, equally false-positive. It is a great shame, in my view, that even top journals (in the above case JAMA) and prestigious funders (in the above case the NIH) cannot (or want not to?) see behind this type of trickery.

Having yesterday been to a ‘Skeptics in the Pub’ event on MEDITATION in Cambridge (my home town since last year) I had to think about the subject quite a bit. As I have hardly covered this topic on my blog, I am today trying to briefly summarise my view on it.

The first thing that strikes me when looking at the evidence on meditation is that it is highly confusing. There seem to be:

- a lack of clear definitions,

- hundreds of studies, most of which are of poor or even very poor quality,

- lots of people with ’emotional baggage’,

- plenty of strange links to cults and religions,

- dozens of different meditation methods and regimen,

- unbelievable claims by enthusiasts,

- lots of weirdly enthusiastic followers.

What was confirmed yesterday is the fact that, once we look at the reliable medical evidence, we are bound to find that the health claims of various meditation techniques are hugely exaggerated. There is almost no strong evidence to suggest that meditation does affect any condition. The small effects that do emerge from some meta-analyses could easily be due to residual bias and confounding; it is not possible to rigorously control for placebo effects in clinical trials of meditation.

Another thing that came out clearly yesterday is the fact that meditation might not be as risk-free as it is usually presented. Several cases of psychoses after meditation are on record; some of these are both severe and log-lasting. How often do they happen? Nobody knows! Like with most alternative therapies, there is no reporting system in place that could possibly give us anything like a reliable answer.

For me, however, the biggest danger with (certain forms of) meditation is not the risk of psychosis. It is the risk of getting sucked into a cult that then takes over the victim and more or less destroys his or her personality. I have seen this several times, and it is a truly frightening phenomenon.

In our now 10-year-old book THE DESKTOP GUIDE TO COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE, we included a chapter on meditation. It concluded that “meditation appears to be safe for most people and those with sufficient motivation to practise regularly will probably find a relaxing experience. Evidence for effectiveness in any indication is week.” Even today, this is not far off the mark, I think. If I had to re-write it now, I would perhaps mention the potential for harm and also add that, as a therapy, the risk/benefit balance of meditation fails to be convincingly positive.

PS

I highly recommend ‘Skeptics in the Pub’ events to anyone who likes stimulating talks and critical thinking.

@Rich It sounds to me as if you are at least partly open-minded, and take a more genuinely scientific approach than most here – i.e. rather than dismissing something with a lot of intriguing evidence behind it (even if much of this evidence is still hotly debated) mainly on the grounds that it ‘sounds a bit silly’, you understand that it’s possible to look at something like acupuncture objectively without being put off by the strange terminology associated with it. I strongly urge you to consult various other outlets as well as this one before coming to any final judgement. http://www.evidencebasedacupuncture.org/ for example is run by intelligent people genuinely trying to present the facts as they see them. Yes, they have an ‘agenda’ in that they are acupuncturists, but I can assure you, having had detailed discussions with some of them, that they are motivated by the urge to see acupuncture help more people rather than anything sinister, and they are trying to present an honest appraisal of the evidence. No doubt virtually everyone here will dismiss everything there with (or without) a cursory glance, but perhaps you won’t fall into that category. I hope you find something of interest there, and come to a balanced opinion.