bias

There are of course 2 types of osteopaths: the US osteopaths who are very close to real doctors, and the osteopaths from all other countries who are practitioners of so-called alternative medicine. This post, as all my posts on this subject, is about the latter category.

I was alerted to a paper entitled ‘Osteopathy under scrutiny’. It goes without saying that I thought it relevant; after all, scrutinising so-called altermative medicine (SCAM), such as osteopathy is one of the aims of this blog. The article itself is in German, but it has an English abstract:

Osteopathic medicine is a medical specialty that enjoys a high level of recognition and increasing popularity among patients. High-quality education and training are essential to ensure good and safe patient treatment. At a superficial glance, osteopathy could be misunderstood as a myth; accurately considered, osteopathic medicine is grounded in medical and scientific knowledge and solid theoretical and practical training. Scientific advances increasingly confirm the empirical experience of osteopathy. Although more studies on its efficacy could be conducted, there is sufficient evidence for a reasonable application of osteopathy. Current scientific studies show how a manually executed osteopathic intervention can induce tissue and even cellular reactions. Because the body actively responds to environmental stimuli, osteopathic treatment is considered an active therapy. Osteopathic treatment is individually applied and patients are seen as an integrated entity. Because of its typical systemic view and scientific interpretation, osteopathic medicine is excellently suited for interdisciplinary cooperation. Further work on external evidence of osteopathy is being conducted, but there is enough knowledge from the other pillars of evidence-based medicine (EBM) to support the application of osteopathic treatment. Implementing careful, manual osteopathic examination and treatment has the potential to cut healthcare costs. To ensure quality, osteopathic societies should be intimately involved and integrated in the regulation of the education, training, and practice of osteopathic medicine.

This does not sound as though the authors know what scutiny is. In fact, the abstract reads like a white-wash of quackery. Why might this be so? To answer this question, we need to look no further than to the ‘conflicts of interest’ where the authors state (my translation): K. Dräger and R. Heller state that, in addition to their activities as further education officers/lecturers for osteopathy (Deutsche Ärztegesellschaft für Osteopathie e. V. (DÄGO) and the German Society for Osteopathic Medicine e. V. (DGOM)) there are no conflicts of interest.

But, to tell you the truth, the article itself is worse, much worse that the abstract. Allow me to show you a few quotes (all my [sometimes free] translations).

- Osteopathic medicine is a therapeutic method based on the scientific findings from medical research.

- [The osteopath makes] diagnostic and therapeutic movements with the hands for evaluating limitations of movement. Thereby, a blocked joint as well as a reduced hydrodynamic or vessel perfusion can be identified.

- The indications of osteopathy are comparable to those of general medicine. Osteopathy can be employed from the birth of a baby up to the palliative care of a dying patient.

- Biostatisticians have recognised the weaknesses of RCTs and meta-analyses, as they merely compare mean values of therapeutic effects, and experts advocate a further evidence level in which statictical correlation is abandonnened in favour of individual causality and definition of cause.

- In ostopathy, the weight of our clinical experience is more important that external evidence.

- Research of osteopathic medicine … the classic cause/effect evaluation cannot apply (in support of this statement, the authors cite a ‘letter to the editor‘ from 1904; I looked it up and found that it does in no way substantiate this claim)

- Findings from anatomy, embryology, physiology, biochemistry and biomechanics which, as natural sciences, have an inherent evidence, strengthen in many ways the plausibility of osteopathy.

- Even if the statistical proof of the effectiveness of neurocranial techniques has so far been delivered only in part, basic research demonstrates that the effects of traction or compression of bogily tissue causes cellular reactions and regulatory processes.

What to make of such statements? And what to think of the fact that nowhere in the entire paper even a hint of ‘scrutiny’ can be detected? I don’t know about you, but for me this paper reflects very badly on both the authors and on osteopathy as a whole. If you ask me, it is an odd mixture of cherry-picking the evidence, misunderstanding science, wishful thinking and pure, unadulterated bullshit.

You urgently need to book into a course of critical thinking, guys!

We are all prone to fall victim to the ‘post hoc ergo propter hoc’ fallacy. It describes the erroneous assumption that something that happened after an event was cased by that event. The fallacy is essentially due to confusing correlation with causation:

- the sun does not rise because the rooster has crowed;

- yellow colouring of the 2nd and 3rd finger of a smoker is not the cause of lung cancer;

- some children developing autism after vaccinations does not mean that autism is caused by vaccination.

As I said, we are all prone to this sort of thing, even though we know better. Scientists, journal editors and reviewers of medical papers, however, should not allow themselves to be fooled by overt cases of the ‘post hoc ergo propter hoc’ fallacy. And if they do, they have lost all credibility – just like the individuals involved in a recent paper on animal homeopathy.

Pododermatitis in penguins usually occurs after changes in normal activity that result from being held captive. It is also called ‘bumlefoot’ (which fails to reflect the seriousness of the condition) and amounts to one of most frequent and important clinical complications in penguins kept in captivity or in rehabilitation centres.

This veterinary case study reports the use of oral homeopathic treatment on acute and chronic pododermatitis in five Magellanic penguins in a zoological park setting. During treatment, the patients remained in the penguins’ living area, and the effect of the treatment on the progression of their lesions was assessed visually once weekly. The treatment consisted of a combination of Arnica montana and Calcarea carbonica.

After treatment, the appearance of the lesions had noticeably improved: in the majority of penguins there was no longer evidence of infection or edema in the feet. The rate of recovery depended on the initial severity of the lesion. Those penguins that still showed signs of infection nevertheless exhibited a clear diminution of the size and thickness of the lesions. Homeopathic treatment did not cause any side effects.

The authors concluded that homeopathy offers a useful treatment option for pododermatitis in captive penguins, with easy administration and without side effects.

So, the homeopathic treatment happened before the recovery and, according to the ‘post hoc ergo propter hoc’ fallacy, the recovery must have been caused by the therapy!

I know, this is a tempting conclusion for a lay person, but it is also an unjustified one, and the people responsible for this paper are not lay people. Pododermitis does often disappear by itself, particularly if the hygenic conditions under which the penguins had been kept are improved. In any case, it is a potentially life-threatening condition (a bit like an infected bed sore in an immobilised human patient) that can be treated, and one should certainly not let a homeopath deal with it.

I think that the researchers who wrote the article, the journal editor who accepted it for publication, and the referees who reviewed the paper should all bow their heads in shame and go on a basic science course (perhaps a course in medical ethics as well) before they are let anywhere near research again.

In 2012, we published a systematic review of adverse effects of homeopathy. Here is its abstract:

Aim: The aim of this systematic review was to critically evaluate the evidence regarding the adverse effects (AEs) of homeopathy.

Method: Five electronic databases were searched to identify all relevant case reports and case series.

Results: In total, 38 primary reports met our inclusion criteria. Of those, 30 pertained to direct AEs of homeopathic remedies; and eight were related to AEs caused by the substitution of conventional medicine with homeopathy. The total number of patients who experienced AEs of homeopathy amounted to 1159. Overall, AEs ranged from mild-to-severe and included four fatalities. The most common AEs were allergic reactions and intoxications. Rhus toxidendron was the most frequently implicated homeopathic remedy.

Conclusion: Homeopathy has the potential to harm patients and consumers in both direct and indirect ways. Clinicians should be aware of its risks and advise their patients accordingly.

The paper prompted a number of angry reactions from proponents of homeopathy who claimed, for instance, that homeopathic remedies are highly diluted and thus safe. We responded that homeopaths can nevertheless be dangerous to patients through neglect and bad advice by homeopaths, and that not all homeopathic remedies are highly diluted, and that some might be toxic because of poor quality control of the manufacturing process.

Now, a different group of researchers have looked at the problem from a slightly different angle and with different methodologies. This systematic review and meta-analysis by researchers from NAFKAM focused on observational studies, as a substantial amount of the research base for homeopathy are observational.

Eight electronic databases, central webpages and journals were searched for eligible studies, and a total of 1,169 studies were identified, 41 were included in this review. Eighteen studies were included in a meta-analysis that made an overall comparison between homeopathy and control (conventional medicine and herbs).

Eighty-seven percent (n = 35) of the studies reported adverse effects. They were graded as CTCAE 1, 2 or 3 and equally distributed between the intervention and control groups. Homeopathic aggravations (homeopaths believe that, when the optimal remedy is given, patients will experience an aggravation of their presenting symptoms) were reported in 22,5% (n = 9) of the studies and graded as CTCAE 1 or 2. The frequency of adverse effects for control versus homeopathy was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). Analysis of sub-groups indicated that, compared to homeopathy, the number of adverse effects was significantly higher for conventional medicine (P = 0.0001), as well as other complementary therapies (P = 0.05).

The authors concluded that adverse effects of homeopathic remedies are consistently reported in observational studies, while homeopathic aggravations are less documented. This meta-analysis revealed that the proportion of patients experiencing adverse effects was significantly higher when receiving conventional medicine and herbs, compared to patients receiving homeopathy. Nonetheless, the development and implementation of a standardized reporting system of adverse effects in homeopathic studies is warranted in order to facilitate future risk assessments.

While these results are interesting, they have to be taken with a pinch of salt and beg a number of questions:

- Is there proof that aggravations exist at all?

- How can one differentiate them from adverse effects?

- As even placebos are known to cause adverse effects (nocebo effects), how can one be sure that the adverse effects of homeopathy are not nocebo effects?

- Is it a good reason to focus on largely inconclusive observational studies, because a substantial amount of the research base for homeopathy are observational?

- Can one produce conclusive results by meta-analysing inconclusive studies?

For me, the most impressive findings of this review is that in total 86 studies had to be excluded by the authors because they reported no adverse effects or aggravations. I think this renders the interpretation of the evidence from the 41 studies they did include even more flimsy. In fact, I don’t see how any meaningful conclusion can be drawn at all – except of course that many researchers of homeopathy violate the rules of research ethics by not reporting adverse effects in their studies.

As to aggravations, we clearly need to rely on placebo controlled studies, if we want to find out whether they exist at all. This we have done in our 2003 paper:

Homeopathic aggravations have often been described anecdotally. However, few attempts have been made to scientifically verify their existence. This systematic review aimed at comparing the frequency of homeopathic aggravations in the placebo and verum groups of double-blind, randomised clinical trials. Eight independent literature searches were carried out to identify all such trials mentioning either adverse effects or aggravations. All studies thus found were validated and data were extracted by both authors. Twenty-four trials could be included. The average number of aggravations was low. In total, 50 aggravations were attributed to patients treated with placebo and 63 to patients treated with homoeopathically diluted remedies. We conclude that this systematic review does not provide clear evidence that the phenomenon of homeopathic aggravations exists.

What is interesting, from my perspective, is the fact that the NAFKAM authors chose to ignore our 2012 paper completely (even though it is highly relevant to their paper and was not published in an obscure journal) and elected to completely misinterpret the findings of our 2003 paper (stating this about it: Grabia and Ernst reported a total of 103 cases of homeopathic aggravations in 3437 participants (3%), while, in fact, our paper demonstrated that aggravations are a homeopathic figment of imagination).

I wonder why.

In the past, NAFKAM did not have the reputation of doing research that was overtly biased towards homeopathy. Recently, the head of the team retired and was replaced by Miek C. Jong who is a co-author of the present review (plus head of CAMcancer, an organisation of which I am a founding member and which did, I think, some good work in the past). She happens to have a long history as a homeopath or homeopathic researcher and is co-author of many papers in this area. Here are three of her conclusions:

- The prognostic questionnaire proved a reliable tool to rank 11 homeopathic medicines by total scores, based on keynote symptoms. This PMS algorithm can be used for the treatment of PMS/PMDD in clinical practice.

- Both complex homeopathic products led to a comparable reduction of URTIs. In the CalSuli-4-02 group, significantly less URTI-related complaints and symptoms and higher treatment satisfaction and tolerability were detected. The observation that the use of antibiotics was reduced upon treatment with the complex homeopathic medications, without the occurrence of complications, is interesting and warrants further investigations on the potential of CalSuli-4-02 as an antibiotic sparing option.

- Our systematic evaluation demonstrated that the reporting rate of ADRs associated with anthroposophic and homeopathic solutions for injection is very low. Most reported ADRs were listed, and one quarter consisted of local reactions. These findings suggest a low risk profile for solutions for injection as therapeutically applied in anthroposophic medicine and homeopathy.

Could it be that, within NAFKAM, the attitude towards homeopathy has changed?

Bloodletting has been used for centuries in many cultures. Its principle, it was assumed, consisted in re-balancing the body’s four humours. Bloodletting had a detrimental effect on most diseases and must have killed millions. It is a good historical example of the harm that ensues, if healthcare adheres to dogma. Today, we know that bloodletting is useful only in rare conditions such as polycythaemia vera or haemochromatosis (and some 30 years ago, a variation of bloodletting, isovolaemic haemodilution, was being discussed as a treatment for circulatory diseases such as intermittent claudication or stroke).

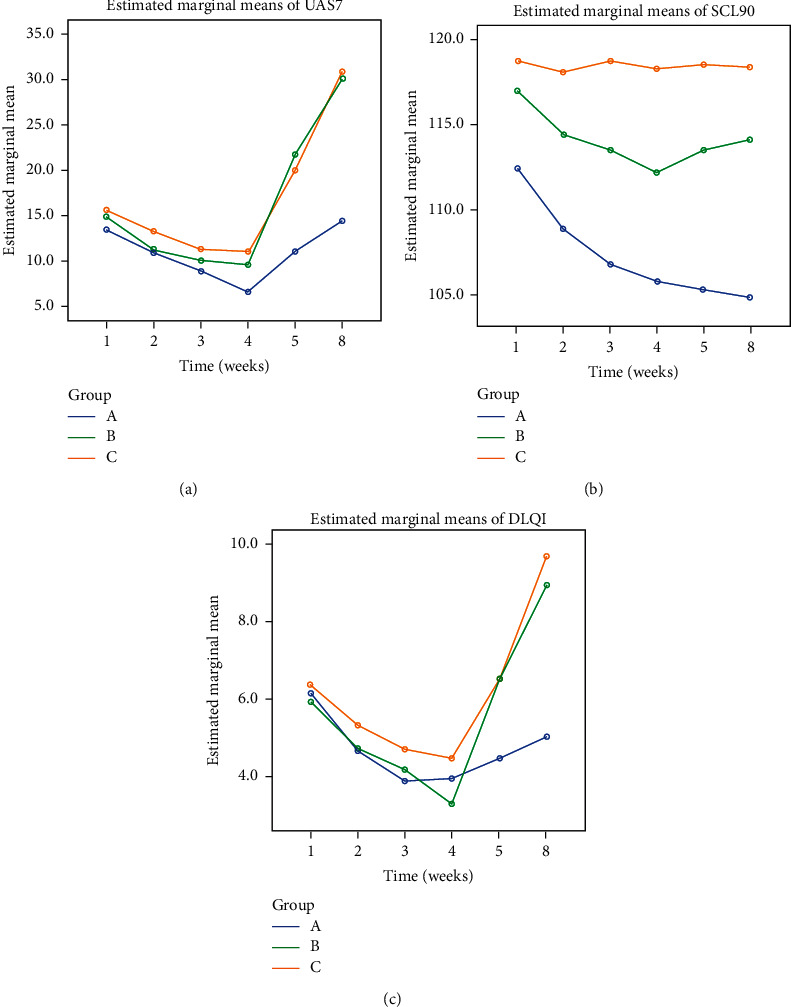

Yet, in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), there are some practitioners who seem to find it hard to concede that ancient treatments might be not as good as they think. Thus, bloodletting has survived in this realm as a therapy for a wide range of conditions. This study assessed the efficacy of bloodletting therapy (acupoint pricking and cupping) in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) in a randomized, control, parallel-group trial.

A total of 174 patients with CIU were randomized into three groups:

- group A was treated with bloodletting therapy and ebastine (an anti-histamine),

- group B was treated with placebo treatment (acupoint pseudopricking and cupping) and ebastine,

- group C was treated with ebastine only.

The treatment period lasted 4 weeks. An intention-to-treat analysis was conducted, and the primary outcome was the effective rate of UAS7 score being reduced to 7 or below after treatment phase.

The effective rates at the end of treatment phase were different among the three groups, which were

- 73.7% in group A,

- 45.6% in group B,

- and 42.9% in group C.

Multiple analysis indicated differences between groups A and B (P < 0.0125) and groups A and C (P < 0.0125) and no difference between groups B and C (P > 0.0125). No severe bloodletting therapy-related adverse events were observed.

The authors concluded that one month of bloodletting therapy combined with ebastine is clinically beneficial compared with placebo treatment combined with ebastine and treatment with ebastine only. Thus, bloodletting therapy can be an effective complementary treatment in CIU.

Amazed?

Me too!

How on earth might bloodletting help for CIU? Luckily, the authors have an answer to this question:

The clinical feature of urticaria with wheals and pruritus coming and going quickly is the manifestation of wind-evil that lurks in and circulates with blood. Hence, in the treatment of urticaria, dispersing wind is the one of the principle methods, and treating blood before wind is an important procedure because when blood flows fluently , wind-evil will resolve spontaneously. Bloodletting therapy is a direct and effective way of regulating blood.

You see, it’s all perfectly clear!

In this case, the results must be true. And the argument that patients might have known in which treatment group they had ended up (and were thus not blinded) can be discarded.

I was alerted to an interview published in an anthroposophical journal with Prof. Dr. med. Harald Matthes. He is the clinical director of the ‘Gemeinschaftskrankenhauses Havelhöhe‘, a hospital of anthroposophic medicine in Berlin where apparently some COVID-19 patients are presently being treated. Anthroposophic medicine is a medical cult created by the mystic, Rudolf Steiner, about 100 years ago that lacks a basis in science, facts or common sense. Here is the two passages from that interview that I find most interesting (my translation/explanation is below):

Es gibt bisher kein spezifisches Covid-19 Medikament aus der konventionellen Medizin. Remdesivir führt in Studien zu keinem signifikant verbesserten Überleben, sondern lediglich zu einer milden Symptomreduktion. Die anfänglich große Studie vor allem an Universitätskliniken mit Hydrochloroquin und Azithromycin erbrachte sogar eine Steigerung der Todesrate. Daher haben anthroposophische Therapiekonzepte mit Steigerung der Selbstheilungskräfte eine große Bedeutung erfahren. Wichtige anthroposophische Arzneimittel waren dabei das Eisen als Meteoreisen oder als Ferrum metallicum praep., der Phosphor, das Stibium sowie das Cardiodoron® und Pneumodoron®, aber auch Bryonia (Zaunrübe) und Tartarus stibiatus (Brechweinstein). Die Erfolge waren sehr gut, da in Havelhöhe bisher kein Covid-19 Patient verstorben ist, bei einer sonstigen Sterblichkeit von ca. 30% aller Covid-19-Intensivpatienten…

100 Jahre Bazillentheorie und die Dominanz eines pathogenetischen Medizinkonzeptes haben zu der von Rudolf Steiner bereits 1909 vorausgesagten Tyrannei im Sozialen geführt. Der Mensch hat ein Mikrobiom und Virom, das unverzichtbar für seine Immunität ist und von der Quantität mächtiger als der Mensch selbst (Mikrobiom 1014 Bakterien mit ca. 1200 Spezies z.B. im Darm bei nur 1012 Körperzellen).

Matthes explains that, so far, no medication has been demonstrated to be effective against COVID-19 infections. Then he continues: “This is the reason why anthroposophic therapies which increase the self-healing powers have gained great importance”, and names the treatments used in his hospital:

- Meteoric Iron (a highly diluted anthroposophic remedy based on iron from meteors),

- Ferrum metallicum praep. (a homeopathic/anthroposophic remedy based on iron),

- Phosphor (a homeopathic remedy based on phosphor),

- Stibium (a homeopathic remedy based on antimony),

- Cardiodoron (a herbal mixture used in anthroposophical medicine),

- Pneumodoron (a herbal mixture used in anthroposophical medicine containing).

Matthes also affirms (my translation):

“The success has so far been very good, since no COVID-19-patient has died in Havelhöhe – with a normal mortality of about 30% of COID_19 patients in intensive care…

100 years of germ theory and the dominance of a pathogenetic concept of medicine have led to the tyranny in the social sphere predicted by Rudolf Steiner as early as 1909. Humans have a microbiome and virom that is indispensable for their immunity and more powerful in quantity than humans themselves (microbiome 1014 bacteria with about 1200 species e.g. in the intestine with only 1012 somatic cells)…”

_________________

The first 4 remedies listed above are highly diluted and contain no active molecules. The last two are less diluted and might therefore contain a few active molecules but in sub-therapeutic doses. Crucially, none of the remedies have been shown to be effective for any condition.

The germ theory of disease which Matthes mentions is, of course, a bit more than a ‘theory’; it is the accepted scientific explanation for many diseases, including COVID-19.

I have cold sweats when I think of anthroposophical doctors who seem to take it less than seriously, while treating desperately ill COVID-19 patients. If I were allowed to ask just three questions to Matthes, I think, it would be these:

- How did you obtain fully informed consent from your patients, including the fact that your remedies are unproven and implausible?

- If you think your results are so good, are you monitoring them closely to publish them urgently, so that other centres might learn from them?

- Do you feel it is ethical to promote unprovn treatments during a health crisis via a publicly available interview before your results have been formally assessed and published?

Acupuncture-moxibustion therapy (AMT) is a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that has been used for centuries in treatment of numerous diseases. Some enthusiasts even seem to advocate it for chemotherapy-induced leukopenia (CIL) The purpose of this review was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acupuncture-moxibustion therapy in treating CIL.

Relevant studies were searched in 9 databases up to September 19, 2020. Two reviewers independently screened the studies for eligibility, extracted data, and assessed the methodological quality of selected studies. Meta-analysis of the pooled mean difference (MD) and risk ratio (RR) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Seventeen studies (1206 patients) were included, and the overall quality of the included studies was moderate. In comparison with medical therapy, AMT has a better clinical efficacy for CIL (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17-1.32; P < 0.00001) and presents advantages in increasing leukocyte count (MD, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.67-1.53; P < 0.00001). Also, the statistical results show that AMT performs better in improving the CIL patients’ Karnofsky performance score (MD, 5.92; 95% CI, 3.03-8.81; P < 0.00001).

The authors concluded that this systematic review and meta-analysis provides updated evidence that AMT is a safe and effective alternative for the patients who suffered from CIL.

A CIL is a serious complication. If I ever were afflicted by it, I would swiftly send any acupuncturist approaching my sickbed packing.

But this is not an evidence-based attitude!!!, I hear some TCM-fans mutter. What more do you want that a systematic review showing it works?

I beg to differ. Why? Because the ‘evidence’ is hardly what critical thinkers can accept as evidence. Have a look at the list of the primary studies included in this review:

- Lin Z. T., Wang Q., Yu Y. N., Lu J. S. Clinical observation of post-chemotherapy-leukopenia treated with ShenMai injectionon ST36. World Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine. 2010;5(10):873–876. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Clinical Observation of Acupoint Moxibustion on Leukopenia Caused by Chemotherapy. Beijing, China: Beijing University of Chinese Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J. Y. Coupling of Yin and Yang between Ginger Moxibustion Improve the Clinical Effect of the Treatment of Chemotherapy Adverse Reaction. Henan, China: Henan University of Chinese Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu D. R., Lu D. X., Wei M., et al. Acupoint injection with addie injection for patients of nausea and vomiting with cisplatin induced by chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2013;29(10):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. E. The Clinical Observation on Treatment of Leukopenia after Chemotherapy with Needle Warming Moxibustion. Hubei, China: Hubei University of Chinese Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y. H., Chi C. Y., Zhang C. Y. Clinical effect of acupuncture and moxibustion on leukopenia after chemotherapy of malignant tumor. Guide of China Medicine. 2014;12(12) [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. N., Zhang W. X., Gu Q. H., Jiao J. P., Liu L., Wei P. K. Protection of herb-partitioned moxibustion on bone marrow suppression of gastric cancer patients in chemotherapy period. Chinese Archives of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2014;32(12):110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. The Clinical Research on Myelosuppression and Quality of Life after Chemotherapy Treated by Grain-Sized Moxibustion. Nanjing, China: Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Lin H., Zhang L., Fan Z. N., Zhang Z. L. Effective research on treating leukopenia following chemotherapy by moxibustion. Clinical Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2015;7(10):35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. W., Wang J. D., Zhao C. Y. Effect of acupuncture on the first WBC reduction after chemotherapy for breast cancer. Beijing Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;35(8):777–779. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D. L., Lu H. Y., Lu Y. Y., Wu L. J. Clinical observation of Qi-blood-supplementing needling for leukopenia after chemotherapy for breast cancer. Shanghai Journal of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2016;35(8):964–966. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xu G. Y. Observation on the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia by moxibustion therapy. Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;51(8):p. 600. [Google Scholar]

- Mo T., Tian H., Yue S. B., Fan Z. N., Zhang Z. L. Clinical observation of acupoint moxibustion on leukocytopenia caused by tumor chemotherapy. World Chinese Medicine. 2016;11(10):2120–2122. [Google Scholar]

- Nie C. M. Nursing observation of acupoint moxibustion in the treatment of leucopenia after chemotherapy. Today Nurse. 2017;4:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. Y. Clinical Research on Post-chemotherapy-leukopenia with Spleen-Kidney Yang Deficiency in Colorectal Cancer Treated with Point-Injection. Yunnan, China: Yunnan University of Chinese Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y. Q, Zhang M. Q, Zhang B. C. Prevention and treatment of leucocytopenia after chemotherapy in patients with malignant tumor with ginger partitioned moxibustion. Chinese Medicine Modern Distance Education of China. 2018;16(21):135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. C., Lian M. J., Miao F. G. Clinical observation of fuzheng moxibustion combined with wenyang shengbai decoction in the treatment of 80 cases of leukopenia after chemotherapy. Hunan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2019;35(3):64–66. [Google Scholar]

Notice anything peculiar?

- The studies are all from China where data fabrication was reported to be rife.

- They are mostly unavailable for checking (why the published adds links that go nowhere is beyond me).

- Many do not look at all like randomised clinical trials (which, according to the authors, was an inclusion criterion).

- Many do not look as though their primary endpoint was the leukocyte count (which, according to the authors, was another inclusion criterion).

Intriguingly, the authors conclude that AMT is not just effective but also ‘safe’. How do they know? According to their own data extraction table, most studies failed to mention adverse effects. And how exactly is acupuncture supposed to increase my leukocyte count? Here is what the authors offer as a mode of action:

I think it is high time that we stop tolerating that the medical literature gets polluted with such nonsense (helped, of course, by journals that are beyond the pale) – someone might actually believe it, in which case it would surely hasten the death of vulnerable patients.

Some consumers believe that research is by definition reliable, and patients are even more prone to this error. When they read or hear that ‘RESEARCH HAS SHOWN…’ or that ‘A RECENT STUDY HAS DEMONSTRATED…’, they usually trust the statements that follow. But is this trust in research and researchers justified? During 25 years that I have been involved in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), I have encountered numerous instances which make me doubt. In this post, I will briefly discuss some the many ways in which consumers can be mislead by apparently sound evidence (for an explanation as to what is and what isn’t evidence, see here).

ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE

I have just finished reading a book by a German Heilpraktiker that is entirely dedicated to SCAM. In it, the author makes hundreds of statements and presents them as evidence-based facts. To many lay people or consumers, this will look convincing, I am sure. Yet, it has one fatal defect: the author fails to offer any real evidence that would back up his statements. The only references provided were those of other books which are equally evidence-free. This popular technique of making unsupported claims allows the author to make assertions without any checks and balances. A lay person is usually unable or unwilling to differentiate such fabulations from evidence, and this technique is thus easy and poular for misleading us about SCAM.

FAKE-EVIDENCE

On this blog, we have encountered this phenomenon ad nauseam: a commentator makes a claim and supports it with some seemingly sound evidence, often from well-respected sources. The few of us who bother to read the referenced articles quickly discover that they do not say what the commentator claimed. This method relies on the reader beeing easily bowled over by some pretend-evidence. As many consumers cannot be bothered to look beyond the smokescreen supplied by such pretenders, the method usually works surprisingly well.

An example: Vidatox is a homeopathic cancer ‘cure’ from Cuba. The Vidatox website clains that it is effective for many cancers. Considering how sensational this claim is, one would expect to find plenty of published articles on Vidatox. However, a Medline search resulted in one paper on the subject. Its authors drew the following conclusion: Our results suggest that the concentration of Vidatox used in the present study has not anti-neoplastic effects and care must be taken in hiring Vidatox in patients with HCC.

The question one often has to ask is this: where is the line between misleading research and fraud?

SURVEYS

There is no area in healthcare that produces more surveys than SCAM. About 500 surveys are published every year! This ‘survey-mania’ has a purpose: it promotes a positive message about SCAM which hypothesis-testing research rarely does.

For a typical SCAM survey, a team of enthusiastic researchers might put together a few questions and design a questionnaire to find out what percentage of a group of individuals have tried SCAM in the past. Subsequently, the investigators might get one or two hundred responses. They then calculate simple descriptive statistics and demonstrate that xy % use SCAM. This finding eventually gets published in one of the many third-rate SCAM journals. The implication then is that, if SCAM is so popular, it must be good, and if it’s good, the public purse should pay for it. Few consumers would realise that this conclusion is little more that a fallacious appeal to popularity.

AVOIDING THE QUESTION

Another popular way of SCAM researchers to mislead the public is to avoid the research questions that matter. For instance, few experts would deny that one of the most urgent issues in chiropractic relates to the risk of spinal manipulations. One would therefore expect that a sizable proportion of the currently published chiropractic research is dedicated to it. Yet, the opposite is the case. Medline currently lists more than 3 000 papers on ‘chiropractic’, but only 17 on ‘chiropractic, harm’.

PILOT-STUDIES

A pilot study is a small scale preliminary study conducted in order to evaluate feasibility, time, cost, adverse events, and improve upon the study design prior to performance of a full-scale research project. Yet, the elementary preconditions are not fulfilled by the plethora of SCAM pilot studies that are currently being published. True pilot studies of SCAM are, in fact, very rare. The reason for the abundance of pseudo-pilots is obvious: they can easily be interpreted as showing encouragingly positive results for whatever SCAM is being tested. Subsequently, SCAM proponents can mislead the public by claiming that there are plenty of positive studies and therefore their SCAM is supported by sound evidence.

‘SAFE‘ STUDY-DESIGNS

As regularly mentioned on this blog, there are several ways to design a study such that the risk of producing a negative result is minimal. The most popular one in SCAM research is the ‘A+B versus B’ design. In this study, for instance, cancer patients who were suffering from fatigue were randomised to receive usual care or usual care plus regular acupuncture. The researchers then monitored the patients’ experience of fatigue and found that the acupuncture group did better than the control group. The effect was statistically significant, and an editorial in the journal where it was published called this evidence “compelling”. Due to a cleverly over-stated press-release, news spread fast, and the study was celebrated worldwide as a major breakthrough in cancer-care.

Imagine you have an amount of money A and your friend owns the same sum plus another amount B. Who has more money? Simple, it is, of course your friend: A+B will always be more than A [unless B is a negative amount]. For the same reason, such “pragmatic” trials will always generate positive results [unless the treatment in question does actual harm]. Treatment as usual plus acupuncture is more than treatment as usual alone, and the former is therefore more than likely to produce a better result. This will be true, even if acupuncture is a pure placebo – after all, a placebo is more than nothing, and the placebo effect will impact on the outcome, particularly if we are dealing with a highly subjective symptom such as fatigue.

A more obvious method for generating false positive results is to omit blinding. The purpose of blinding the patient, the therapist and the evaluator of the group allocation in clinical trials is to make sure that expectation is not a contributor to the result. Expectation might not move mountains, but it can certainly influence the result of a clinical trial. Patients who hope for a cure regularly do get better, even if the therapy they receive is useless, and therapists as well as evaluators of the outcomes tend to view the results through rose-tinted spectacles, if they have preconceived ideas about the experimental treatment.

Failure to randomise is another source of bias which can mislead us. If we allow patients or trialists to select or chose which patients receive the experimental and which get the control-treatment, it is likely that the two groups differ in a number of variables. Some of these variables might, in turn, impact on the outcome. If, for instance, doctors allocate their patients to the experimental and control groups, they might select those who will respond to the former and those who don’t to the latter. This may not happen with intent but through intuition or instinct: responsible health care professionals want those patients who, in their experience, have the best chances to benefit from a given treatment to receive that treatment. Only randomisation can, when done properly, make sure we are comparing comparable groups of patients. Non-randomisation can easily generate false-positive findings.

It is also possible to mislead people with studies which do not test whether an experimental treatment is superior to another one (often called superiority trials), but which assess whether it is equivalent to a therapy that is generally accepted to be effective. The idea is that, if both treatments produce similarly positive results, both must be effective. Such trials are called non-superiority or equivalence trials, and they offer a wide range of possibilities for misleading us. If, for example, such a trial has not enough patients, it might show no difference where, in fact, there is one. Let’s consider a simple, hypothetical example: someone comes up with the idea to compare antibiotics to acupuncture as treatments of bacterial pneumonia in elderly patients. The researchers recruit 10 patients for each group, and the results reveal that, in one group, 2 patients died, while, in the other, the number was 3. The statistical tests show that the difference of just one patient is not statistically significant, and the authors therefore conclude that acupuncture is just as good for bacterial infections as antibiotics.

Even trickier is the option to under-dose the treatment given to the control group in an equivalence trial. In the above example, the investigators might subsequently recruit hundreds of patients in an attempt to overcome the criticism of their first study; they then decide to administer a sub-therapeutic dose of the antibiotic in the control group. The results would then seemingly confirm the researchers’ initial finding, namely that acupuncture is as good as the antibiotic for pneumonia. Acupuncturists might then claim that their treatment has been proven in a very large randomised clinical trial to be effective for treating this condition. People who do not happen to know the correct dose of the antibiotic could easily be fooled into believing them.

Obviously, the results would be more impressive, if the control group in an equivalence trial received a therapy which is not just ineffective but actually harmful. In such a scenario, even the most useless SCAM would appear to be effective simply because it is less harmful than the comparator.

A variation of this theme is the plethora of controlled clinical trials in SCAM which compare one unproven therapy to another unproven treatment. Perdicatbly, the results would often indicate that there is no difference in the clinical outcome experienced by the patients in the two groups. Enthusiastic SCAM researchers then tend to conclude that this proves both treatments to be equally effective. The more likely conclusion, however, is that both are equally useless.

Another technique for misleading the public is to draw conclusions which are not supported by the data. Imagine you have generated squarely negative data with a trial of homeopathy. As an enthusiast of homeopathy, you are far from happy with your own findings; in addition you might have a sponsor who puts pressure on you. What can you do? The solution is simple: you only need to highlight at least one positive message in the published article. In the case of homeopathy, you could, for instance, make a major issue about the fact that the treatment was remarkably safe and cheap: not a single patient died, most were very pleased with the treatment which was not even very expensive.

OMISSION

A further popular method for misleading the public is the outright omission findings that SCAM researchers do not like. If the aim is that the public believe the myth that all SCAM is free of side-effects, SCAM researchers only need to omit reporting them in clinical trials. On this blog, I have alerted my readers time and time again to this common phenomenon. We even assessed it in a systematic review. Sixty RCTs of chiropractic were included. Twenty-nine RCTs did not mention adverse effects at all. Sixteen RCTs reported that no adverse effects had occurred. Complete information on incidence, severity, duration, frequency and method of reporting of adverse effects was included in only one RCT.

Most trails have many outcome measures; for instance, a study of acupuncture for pain-control might quantify pain in half a dozen different ways, it might also measure the length of the treatment until pain has subsided, the amount of medication the patients took in addition to receiving acupuncture, the days off work because of pain, the partner’s impression of the patient’s health status, the quality of life of the patient, the frequency of sleep being disrupted by pain etc. If the researchers then evaluate all the results, they are likely to find that one or two of them have changed in the direction they wanted (especially, if they also include half a dozen different time points at which these variables are quatified). This can well be a chance finding: with the typical statistical tests, one in 20 outcome measures would produce a significant result purely by chance. In order to mislead us, the researchers only need to “forget” about all the negative results and focus their publication on the ones which by chance have come out as they had hoped.

FRAUD

When it come to fraud, there is more to chose from than one would have ever wished for. We and others have, for example, shown that Chinese trials of acupuncture hardly ever produce a negative finding. In other words, one does not need to read the paper, one already knows that it is positive – even more extreme: one does not need to conduct the study, one already knows the result before the research has started. This strange phenomenon indicates that something is amiss with Chinese acupuncture research. This suspicion was even confirmed by a team of Chinese scientists. In this systematic review, all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of acupuncture published in Chinese journals were identified by a team of Chinese scientists. A total of 840 RCTs were found, including 727 RCTs comparing acupuncture with conventional treatment, 51 RCTs with no treatment controls, and 62 RCTs with sham-acupuncture controls. Among theses 840 RCTs, 838 studies (99.8%) reported positive results from primary outcomes and two trials (0.2%) reported negative results. The percentages of RCTs concealment of the information on withdraws or sample size calculations were 43.7%, 5.9%, 4.9%, 9.9%, and 1.7% respectively. The authors concluded that publication bias might be major issue in RCTs on acupuncture published in Chinese journals reported, which is related to high risk of bias. We suggest that all trials should be prospectively registered in international trial registry in future.

A survey of clinical trials in China has revealed fraudulent practice on a massive scale. China’s food and drug regulator carried out a one-year review of clinical trials. They concluded that more than 80 percent of clinical data is “fabricated“. The review evaluated data from 1,622 clinical trial programs of new pharmaceutical drugs awaiting regulator approval for mass production. Officials are now warning that further evidence malpractice could still emerge in the scandal.

I hasten to add that fraud in SCAM research is certainly not confined to China. On this blog, you will find plenty of evidence for this statement, I am sure.

CONCLUSION

Research is obviously necessary, if we want to answer the many open questions in SCAM. But sadly, not all research is reliable and much of SCAM research is misleading. Therefore, it is always necessary to be on the alert and apply all the skills of critical evaluation we can muster.

Despite reported widespread use of dietary supplements by cancer patients, few empirical data with regard to their safety or efficacy exist. Because of concerns that antioxidants could reduce the cytotoxicity of chemotherapy, a prospective study was carried out to evaluate associations between supplement use and breast cancer outcomes.

Patients with breast cancer randomly assigned to an intergroup metronomic trial of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel were queried on their use of supplements at registration and during treatment (n =1,134). Cancer recurrence and survival were indexed at 6 months after enrollment.

There were indications that use of any antioxidant supplement (vitamins A, C, and E; carotenoids; coenzyme Q10) both before and during treatment was associated with an increased hazard of recurrence and, to a lesser extent, death. Relationships with individual antioxidants were weaker perhaps because of small numbers. For non-antioxidants, vitamin B12 use both before and during chemotherapy was significantly associated with poorer disease-free survival and overall survival. Use of iron during chemotherapy was significantly associated with recurrence as was use both before and during treatment. Results were similar for overall survival. Multivitamin use was not associated with survival outcomes.

The authors concluded that associations between survival outcomes and use of antioxidant and other dietary supplements both before and during chemotherapy are consistent with recommendations for caution among patients when considering the use of supplements, other than a multivitamin, during chemotherapy.

These data are interesting but, for a range of reasons, not compelling. There might have been several important confounding factors distorting the findings. Even though clinical and life-style variables were statistically adjusted for in this study, it might still be possible that supplement users and non-users were not comparable in impotant prognostic variables. Simply put, sicker patients might be more likely to use supplements and would then have worse outcomes not because of the supplements but their disease severity.

Moreover, it seems important to note that other research showed the opposite effects. For instance, a study prospectively examined the associations between antioxidant use after breast cancer (BC) diagnosis and BC outcomes in 2264 women. The cohort included women who were diagnosed with early stage, primary BC from 1997 to 2000 who enrolled, on average, 2 years postdiagnosis. Baseline data were collected on antioxidant supplement use since diagnosis and other factors. BC recurrence and mortality were ascertained, and hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated.

Antioxidant supplement use after diagnosis was reported by 81% of women. Among antioxidant users, frequent use of vitamin C and vitamin E was associated with a decreased risk of BC recurrence. Vitamin E use was associated with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality. Conversely, frequent use of combination carotenoids was associated with increased risk of death from BC and all-cause mortality.

The authors concluded that frequent use of vitamin C and vitamin E in the period after BC diagnosis was associated with a decreased likelihood of recurrence, whereas frequent use of combination carotenoids was associated with increased mortality. The effects of antioxidant supplement use after diagnosis likely differ by type of antioxidant.

Yet another study provided limited support for the hypothesis that antioxidant supplements may reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence or breast cancer-related mortality.

Confused?

Me too!

What is needed, it seems, is a systematic review of all these contradicting studies. A 2009 review is available of the associations between antioxidant supplement use during breast cancer treatment and patient outcomes.

Inclusion criteria were: two or more subjects; clinical trial or observational study design; use of antioxidant supplements (vitamin C, vitamin E, antioxidant combinations, multivitamins, glutamine, glutathione, melatonin, or soy isoflavones) during chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or hormonal therapy for breast cancer as exposures; treatment toxicities, tumor response, recurrence, or survival as outcomes.

A total of 22 articles met the criteria. Their findings did not support any conclusions regarding the effects of individual antioxidant supplements during conventional breast cancer treatment on toxicities, tumor response, recurrence, or survival. A few studies suggested that antioxidant supplements might decrease side effects associated with treatment, including vitamin E for hot flashes due to hormonal therapy and glutamine for oral mucositis during chemotherapy. Underpowered trials suggest that melatonin may enhance tumor response during treatment.

The authors concluded that the evidence is currently insufficient to inform clinician and patient guidelines on the use of antioxidant supplements during breast cancer treatment. Thus, well designed clinical trials and observational studies are needed to determine the short- and long-term effects of such agents.

Still confused?

Me too!

Antioxidants seem to have evolved as parts of elaborate networks in which each substance plays slightly different roles. This means that each antioxidant has a different spectrum of actions. And this means that it is probably not very constructive to lump them all together and excect to see uniform effects. What we would need to create more clarity is a series of RCTs on single antioxidants. But who is going to fund them? We might be waiting a long time for more clarity. Meanwhile, consuming a healthy and well-balanced diet might be the best advice for cancer patients and everyone else.

Misinformation by chiropractors is unfortunately nothing new and has been discussed ad nauseam on this blog. It is tempting to ask whether chiropractors have lost (or more likely never had) the ability to ditinguish real information from misinformation or substantiated from unsubstantiated claims. During the pandemic, the phenomenon of chiropractic misinformation has become even more embarrassingly obvious, as this new article highlights.

Chiropractors made statements on social media claiming that chiropractic treatment can prevent or impact COVID-19. The rationale for these claims is that spinal manipulation can impact the nervous system and thus improve immunity. These beliefs often stem from nineteenth-century chiropractic concepts. The authors of the paper are aware of no clinically relevant scientific evidence to support such statements.

The investigators explored the internet and social media to collect examples of misinformation from Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand regarding the impact of chiropractic treatment on immune function. They discussed the potential harm resulting from these claims and explore the role of chiropractors, teaching institutions, accrediting agencies, and legislative bodies.

The authors conclude as follows: In this search of public media in Europe, North America, New Zealand, and Australia, we discovered many cases of misinformation. Claims of chiropractic treatment improving immunity conflict with the advice from authorities and the scientific consensus. The science referenced by these claims is missing, flawed or has no clinical relevance. Consequently, their claims about clinical effectiveness are spurious at best and misleading at worst. However, our examples cannot be used to make statements about the magnitude of the problem among practitioners as our samples were not intended to be representative. For that reason, we also did not include an analysis of the arguments provided in the various postings. In view of the seriousness of the topic, it would be relevant to conduct a systematic study on a representative sample of public statements, to better understand these issues. Our search illustrates the possible danger to public health of misinformation posted on social media and the internet. This situation provides an opportunity for growth and maturation for the chiropractic profession. We hope that individual chiropractors will reflect on and improve their communication and practices. Further, we hope that the chiropractic teaching institutions, regulators, and professional organisations will always demonstrate responsible leadership in their respective domains by acting to ensure that all chiropractors understand and uphold their fiduciary duties.

Several previous papers have found similar things, e.g.: Twitter activity about SMT and immunity increased during the COVID-19 crisis. Results from this work have the potential to help policy makers and others understand the impact of SMT misinformation and devise strategies to mitigate its impact.

The pandemic has crystallised the embarrassment about chiropractic false claims. Yet, the phenomenon of chiropractors misleading the public has long been known and arguably is even more important when it relates to matters other than COVID-19. Ten years ago, we published this paper:

Background: Some chiropractors and their associations claim that chiropractic is effective for conditions that lack sound supporting evidence or scientific rationale. This study therefore sought to determine the frequency of World Wide Web claims of chiropractors and their associations to treat, asthma, headache/migraine, infant colic, colic, ear infection/earache/otitis media, neck pain, whiplash (not supported by sound evidence), and lower back pain (supported by some evidence).

Methods: A review of 200 chiropractor websites and 9 chiropractic associations’ World Wide Web claims in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States was conducted between 1 October 2008 and 26 November 2008. The outcome measure was claims (either direct or indirect) regarding the eight reviewed conditions, made in the context of chiropractic treatment.

Results: We found evidence that 190 (95%) chiropractor websites made unsubstantiated claims regarding at least one of the conditions. When colic and infant colic data were collapsed into one heading, there was evidence that 76 (38%) chiropractor websites made unsubstantiated claims about all the conditions not supported by sound evidence. Fifty-six (28%) websites and 4 of the 9 (44%) associations made claims about lower back pain, whereas 179 (90%) websites and all 9 associations made unsubstantiated claims about headache/migraine. Unsubstantiated claims were made about asthma, ear infection/earache/otitis media, neck pain,

Conclusions: The majority of chiropractors and their associations in the English-speaking world seem to make therapeutic claims that are not supported by sound evidence, whilst only 28% of chiropractor websites promote lower back pain, which is supported by some evidence. We suggest the ubiquity of the unsubstantiated claims constitutes an ethical and public health issue.

It makes it clear that the misleading information of chiropractors is a serious problem. And I find it disappointing to see that so little has been done about it, and that progress seems so ellusive.

This, of course, begs the question, where does all this misinformation come from? The authors of the new paper stated that beliefs often stem from nineteenth-century chiropractic concepts. This, I believe, is very true and it gives us an important clue. It suggests that, because it is good for business, chiro schools are still steeped in obsolete notions of pseudo- and anti-science. Thus, year after year, they seem to churn out new generations of naively willing victims of the Dunning Kruger effect.

We have often heard it said on this blog and elsewhere that chiropractors are making great strides towards reforming themselves and becoming an evidence-based profession. In view of the data cited above, this does not ring all that true, I am afraid. Is the picture that emerges not one of a profession deeply embroiled in BS with but a few fighting a lost battle to clean up the act?

Governments and key institutions have had to implement decisive responses to the danger posed by the coronavirus pandemic. Imposed change will increase the likelihood that alternative explanations take hold. In a proportion of the general population there may be strong scepticism, fear of being misled, and false conspiracy theories.

The objectives of this survey were to estimate the prevalence of conspiracy thinking about the pandemic and test associations with reduced adherence to government guidelines. The survey was conducted in May 2020 as a non-probability online survey with 2501 adults in England, quota sampled to match the population for age, gender, income, and region.

Approximately 50% of this population showed little evidence of conspiracy thinking, 25% showed a degree of endorsement, 15% showed a consistent pattern of endorsement, and 10% had very high levels of endorsement. Higher levels of coronavirus conspiracy thinking were associated with less adherence to all government guidelines and less willingness to take diagnostic or antibody tests or to be vaccinated. Such ideas were also associated with

- paranoia,

- general vaccination conspiracy beliefs,

- climate change conspiracy belief,

- a conspiracy mentality, and distrust in institutions and professions.

Holding coronavirus conspiracy beliefs was also associated with being more likely to share opinions.

The authors concluded that, in England, there is appreciable endorsement of conspiracy beliefs about coronavirus. Such ideas do not appear confined to the fringes. The conspiracy beliefs connect to other forms of mistrust and are associated with less compliance with government guidelines and greater unwillingness to take up future tests and treatment.

The authors also state that the coronavirus conspiracy ideas ascribe malevolent intent to individuals, groups, and organisations based on what are likely to be long-standing prejudices. For instance, almost half of participants endorsed to some degree the idea that ‘Coronavirus is a bioweapon developed by China to destroy the West’ and around one-fifth endorsed to some degree that ‘Jews have created the virus to collapse the economy for financial gain’.

The survey did not include questions about so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). This is a great shame, in my view. We know from previous research that people who adhere to conspiracy theories feel strongly that SCAM is being suppressed via some sinister complot by the establishment. Moreover, we know that SCAM enthusiasts tend to believe in vaccination conspiracy theories. One might therefore expect that proponents of SCAM are also prone to conspiracy beliefs about coronavirus.

When reading some of the comments on this blog, I have little doubt that this is, in fact, the case.