back pain

The purpose of this study was to describe changes in opioid-therapy prescription rates after a family medicine practice included on-site chiropractic services. It was designed as a retrospective analysis of opioid prescription data. The database included opioid prescriptions written for patients seeking care at the family medicine practice from April 2015 to September 2018. In June 2016, the practice reviewed and changed its opioid medication practices. In April 2017, the practice included on-site chiropractic services. Opiod-therapy use was defined as the average rate of opioid prescriptions overall medical providers at the practice.

There was a significant decrease of 22% in the average monthly rate of opioid prescriptions after the inclusion of chiropractic services (F1,40 = 10.69; P < .05). There was a significant decrease of 32% in the prescribing rate of schedule II opioids after the inclusion of chiropractic services (F2,80 = 6.07 for the Group × Schedule interaction; P < .05). The likelihood of writing schedule II opioid prescriptions decreased by 27% after the inclusion of chiropractic services (odds ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.90). Changes in opioid medication practices by the medical providers included prescribing a schedule III or IV opioid rather than a schedule II opioid (F6,76 = 29.81; P < .05) and a 30% decrease in the daily doses of opioid prescriptions (odds ratio, 0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-0.98).

The authors concluded that this study demonstrates that there were decreases in opioid-therapy prescribing rates after a family medicine practice included on-site chiropractic services. This suggests that inclusion of chiropractic services may have had a positive effect on prescribing behaviors of medical physicians, as they may have been able to offer their patients additional nonpharmaceutical options for pain management.

The authors are correct in concluding the inclusion of chiropractic services MAY have had a positive effect. And then again, it may not!

Cause and effect cannot be established by correlation alone.

CORRELATION IS NOT CAUSATION!

And even if the inclusion of chiropractic services caused the positive effect, it would not prove that chiropractic is effective in the management of pain. It would only mean that the physicians had an option that helped them to write fewer opioid prescriptions. Had they hired a crystal healer or a homeopath or a faith healer or any other practitioner of an ineffective therapy, the findings might have been very similar.

The long and short of it is this: if we want to use fewer opioids, there is only one way to achieve it: we must prescribe less.

The objective of this systematic review was to examine whether back pain is associated with increased mortality risk and, if so, whether this association varies by age, sex, and back pain severity.

A systematic search of published literature was conducted and English-language prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of back pain with all-cause mortality with follow-up periods >5 years were included. Three reviewers independently screened studies, abstracted data, and appraised risk of bias using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool. A random-effects meta-analysis estimated combined odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), using the most adjusted model from each study. Potential effect modification by a priori hypothesized factors (age, sex, and back pain severity) was evaluated with meta-regression and stratified estimates.

Eleven studies with a total of 81,337 participants were included. Follow-up periods ranged from 5 to 23 years. The presence of any back pain, compared to none, was not associated with an increase in mortality (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.16). However, back pain was associated with mortality in studies of women (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.46) and among adults with more severe back pain (OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.40).

The authors concluded that back pain was associated with a modest increase in all-cause mortality among women and those with more severe back pain.

I bet that back pain is associated with hundreds of things. The question is whether there might be a causal association; could it be that people die earlier BECAUSE of back pain?

Unless someone’s back pain is so unbearable that she commits suicide, I cannot see how the two can be directly linked in a cause/effect relationship. But there could be indirect causal links. For instance, certain cancers can cause both back pain and death. Or someone’s back pain might make him take treatment against a life-threatening condition less seriously and thus hasten his death.

It has also occurred to me that chiropractors might jump on the bandwagon and use the association between back pain and mortality for boosting their business. Something like this:

Back pain is a risk factor for premature death.

Come to us, and we treat your back pain.

This will make you live longer.

Chiropractic prolongs life!

That would, of course, be daft. Firstly, chiropractic is not all that effective for back pain (or anything else). Secondly, getting rid of back pain is unlikely to prolong your life.

Correlation is not causation!

The objective of this study was to assess a new treatment, Medi-Taping, which aims at reducing complaints by treating pelvic obliquity with a combination of manual treatment of trigger points and kinesio taping in a pragmatic RCT with pilot character.

One hundred ten patients were randomized at two study centers either to Medi-Taping or to a standard treatment consisting of patient education and physiotherapy as control. Treatment duration was 3 weeks. Measures were taken at baseline, end of treatment and at follow-up after 2 months. Main outcome criteria were low back pain measured with VAS, the Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS) and the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire (ODQ).

Patients of both groups benefited from the treatment by medium to large effect sizes. All effects were pointing towards the intended direction. While Medi-Taping showed slightly better improvement rates, there were no significant differences for the primary endpoints between groups at the end of treatment (VAS: mean difference in change 0.38, 95-CI [- 0.45; 1.21] p = 0.10; ODQ 2.35 [- 0.77; 5.48] p = 0.14; CPGS – 0.19 [- 0.46; 0.08] p = 0.64) and at follow-up. Health-related quality of life was significantly higher (p = .004) in patients receiving Medi-Taping compared to controls.

The authors concluded that Medi-Taping, a purported way of correcting pelvic obliquity and chronic tension resulting from it, is a treatment modality similar in effectiveness to complex physiotherapy and patient education.

This conclusion is obviously nonsense! The authors stated that their trial has ‘pilot character’. The study was not designed as an equivalence trial. Thus it is improper to draw conclusions about the comparative effectiveness of Medi-Taping.

Having clarified this crucial point, we might ask, what is this new therapy called Medi-Taping? This is how the authors of the above paper describe the technique:

…sessions started with an assessment of leg length difference. Patients were asked to lie on their back and the legs were slightly stretched by a soft pull at the ankles. Next, a continuous horizontal line was drawn on the inside of both calves indicating the position of the calves relative to each other. Then the patient was asked to sit up with the legs remaining outstretched. This procedure results in a shift of the line between the two calves for most people. This shift was measured in millimeters as leg length difference.

The patient was then asked to stretch out, lying supine, and the therapist palpated any myogeloses (areas of abnormal hardening in a muscle) and tense muscles areas that could be found next to the cervical spine between the base of the skull and seventh cervical vertebra on both sides. After this treatment the leg length difference assessment was repeated. If there was still a substantial difference. The same treatment was also performed on the thoracic and lumbar spine. Also, the mandibular joint was assessed for tense muscles and, if necessary, treated by palpation.

Next, the leg length difference was assessed again and several tapes were applied as follows: First, two parallel tapes were fixed on both sides of the spine above the erector spinae muscles ranging from the base of the skull to the sacrum. For the application patients were asked to bend forward and to lean on a bench. This position stretches the back and its anatomical structure before applying the tape and thus provides the tape with tension before fixing it. Next a star-shaped pattern of tape (three stripes meeting in one point) was placed on the lower back while the patient was still in the same bent position. Thus, the star tape covered the area of the patient’s maximum pain and additionally stabilized the sacroiliac joint. This tape was placed with maximum tension in the middle section by stretching the tape before application, with the ends (approx. 5 cm) applied without tension. If after this procedure there was still residual pain, a third tape was placed at the gluteus maximus muscle. This tape was first fixed distally from the greater trochanter then stretched up to approx. 80% of the possible tension before the other end was placed on the sacrum. On average six tapes were applied for the gluteus tape.

Patients were instructed to keep the tapes on as long as they stuck to the skin. If the patients had recurring low back pain (LBP) within the same week, they were asked to see the therapist again immediately. Otherwise, the second and the third treatment were scheduled once a week for the following 2 weeks, respectively.

(Elsewhere MEDI-Taping is described differently as a technique using an elastic tape. The tape comes in different colors that are used depending on the patient’s need. The fabric and adhesive are made from cotton and other all natural materials. The tape can be ‘stretched’ in order to better support a given joint or muscle. Through the stretch, the underlying areas are relieved of tension, circulation is improved, and as a result injuries are healing faster. While it is applied to the skin, the tape gently massages the affected area as the body is moving. As the tape is applied, an improvement in motor function and pain relief should be felt immediately.)

Considering the above, I think that the most likely explanation of the outcome of this study (if it ever got confirmed in a properly designed equivalence trial) is that Medi-Taping itself is fairly useless. The fact that it did as well as (more precisely perhaps not worse than) standard physiotherapy is due to its exotic and novel flair which raised expectations and thus contributed to a large placebo response.

Whether my speculation is true or not, I don’t feel that Medi-Taping is the solution to back or any other problems.

PS

The senior author of this study is Harad Walach who has been a regular feature on this blog, and I could not help but notice that he now has 4 affiliations:

- Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health, Freiburg, Germany.

- Pediatric Clinic, Medical University Poznan, Poznan, Poland.

- Department of Psychology and Psychotherapy, University Witten-Herdecke, Witten, Germany.

- CHS Institute, Berlin, Germany.

Low back pain must be one of the most frequent reasons for patients to seek out some so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). It would therefore be important that the information they get is sound. But is it?

The present study sought to assess the quality of web-based consumer health information available at the intersection of LBP and CAM. The investigators searched Google using six unique search terms across four English-speaking countries. Eligible websites contained consumer health information in the context of CAM for LBP. They used the DISCERN instrument, which consists of a standardized scoring system with a Likert scale from one to five across 16 questions, to conduct a quality assessment of websites.

Across 480 websites identified, 32 were deemed eligible and assessed using the DISCERN instrument. The mean overall rating across all websites 3.47 (SD = 0.70); Summed DISCERN scores across all websites ranged from 25.5-68.0, with a mean of 53.25 (SD = 10.41); the mean overall rating across all websites 3.47 (SD = 0.70). Most websites reported the benefits of numerous CAM treatment options and provided relevant information for the target audience clearly, but did not adequately report the risks or adverse side-effects adequately.

The authors concluded that despite some high-quality resources identified, our findings highlight the varying quality of consumer health information available online at the intersection of LBP and CAM. Healthcare providers should be involved in the guidance of patients’ online information-seeking.

In the past, I have conducted several similar surveys, for instance, this one:

Background: Low back pain (LBP) is expected to globally affect up to 80% of individuals at some point during their lifetime. While conventional LBP therapies are effective, they may result in adverse side-effects. It is thus common for patients to seek information about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) online to either supplement or even replace their conventional LBP care. The present study sought to assess the quality of web-based consumer health information available at the intersection of LBP and CAM.

Methods: We searched Google using six unique search terms across four English-speaking countries. Eligible websites contained consumer health information in the context of CAM for LBP. We used the DISCERN instrument, which consists of a standardized scoring system with a Likert scale from one to five across 16 questions, to conduct a quality assessment of websites.

Results: Across 480 websites identified, 32 were deemed eligible and assessed using the DISCERN instrument. The mean overall rating across all websites 3.47 (SD = 0.70); Summed DISCERN scores across all websites ranged from 25.5-68.0, with a mean of 53.25 (SD = 10.41); the mean overall rating across all websites 3.47 (SD = 0.70). Most websites reported the benefits of numerous CAM treatment options and provided relevant information for the target audience clearly, but did not adequately report the risks or adverse side-effects adequately.

Conclusion: Despite some high-quality resources identified, our findings highlight the varying quality of consumer health information available online at the intersection of LBP and CAM. Healthcare providers should be involved in the guidance of patients’ online information-seeking.

Or this one:

Background: Some chiropractors and their associations claim that chiropractic is effective for conditions that lack sound supporting evidence or scientific rationale. This study therefore sought to determine the frequency of World Wide Web claims of chiropractors and their associations to treat, asthma, headache/migraine, infant colic, colic, ear infection/earache/otitis media, neck pain, whiplash (not supported by sound evidence), and lower back pain (supported by some evidence).

Methods: A review of 200 chiropractor websites and 9 chiropractic associations’ World Wide Web claims in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States was conducted between 1 October 2008 and 26 November 2008. The outcome measure was claims (either direct or indirect) regarding the eight reviewed conditions, made in the context of chiropractic treatment.

Results: We found evidence that 190 (95%) chiropractor websites made unsubstantiated claims regarding at least one of the conditions. When colic and infant colic data were collapsed into one heading, there was evidence that 76 (38%) chiropractor websites made unsubstantiated claims about all the conditions not supported by sound evidence. Fifty-six (28%) websites and 4 of the 9 (44%) associations made claims about lower back pain, whereas 179 (90%) websites and all 9 associations made unsubstantiated claims about headache/migraine. Unsubstantiated claims were made about asthma, ear infection/earache/otitis media, neck pain,

Conclusions: The majority of chiropractors and their associations in the English-speaking world seem to make therapeutic claims that are not supported by sound evidence, whilst only 28% of chiropractor websites promote lower back pain, which is supported by some evidence. We suggest the ubiquity of the unsubstantiated claims constitutes an ethical and public health issue.

The findings were invariably disappointing and confirmed those of the above paper. As it is nearly impossible to do much about this lamentable situation, I can only think of two strategies for creating progress:

- Advise patients not to rely on Internet information about SCAM.

- Provide reliable information for the public.

Both describe the raison d’etre of my blog pretty well.

Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is popular, but does it work? On this blog, we have often discussed that there are good reasons to doubt it.

This study compared the efficacy of standard OMT vs sham OMT for reducing low back pain (LBP)-specific activity limitations at 3 months in persons with nonspecific subacute or chronic LBP. It was designed as a prospective, parallel-group, single-blind, single-center, sham-controlled randomized clinical trial. 400 patients with nonspecific subacute or chronic LBP were recruited from a tertiary care center in France starting and randomly allocated to interventions in a 1:1 ratio.

Six sessions (1 every 2 weeks) of standard OMT or sham OMT delivered by osteopathic practitioners. For both

experimental and control groups, each session lasted 45 minutes and consisted of 3 periods: (1) interview focusing on pain location, (2) full osteopathic examination, and (3) intervention consisting of standard or sham OMT. In both groups, practitioners assessed 7 anatomical regions for dysfunction (lumbar spine, root of mesentery, diaphragm, and atlantooccipital, sacroiliac, temporomandibular, and talocrural joints) and applied sham OMT to all areas or standard OMT to those that were considered dysfunctional.

The primary endpoint was the mean reduction in LBP-specific activity limitations at 3 months as measured by the self-administered Quebec Back Pain Disability Index. Secondary outcomes were the mean reduction in LBP-specific activity limitations; mean changes in pain and health-related quality of life; number and duration of sick leave, as well as the number of LBP episodes at 12 months, and the consumption of analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at 3 and 12 months. Adverse events were self-reported at 3, 6, and 12 months.

A total of 200 participants were randomly allocated to standard OMT and 200 to sham OMT, with 197 analyzed in each group; the median (range) age at inclusion was 49.8 (40.7-55.8) years, 235 of 394 (59.6%) participants were women, and 359 of 393 (91.3%) were currently working. The mean (SD) duration of the current LBP episode had been 7.5 (14.2) months. Overall, 164 (83.2%) patients in the standard OMT group and 159 (80.7%) patients in the sham OMT group had the primary outcome data available at 3 months.

The mean (SD) Quebec Back Pain Disability Index scores were:

- 31.5 (14.1) at baseline and 25.3 (15.3) at 3 months in the OMT-group,

- 27.2 (14.8) at baseline and 26.1 (15.1) at 3 months in the sham group.

The mean reduction in LBP-specific activity limitations at 3 months was -4.7 (95% CI, -6.6 to -2.8) and -1.3 (95% CI, -3.3 to 0.6) for the standard OMT and sham OMT groups, respectively (mean difference, -3.4; 95% CI, -6.0 to -0.7; P = .01). At 12 months, the mean difference in mean reduction in LBP-specific activity limitations was -4.3 (95% CI, -7.6 to -1.0; P = .01), and at 3 and 12 months, the mean difference in mean reduction in pain was -1.0 (95% CI, -5.5 to 3.5; P = .66) and -2.0 (95% CI, -7.2 to 3.3; P = .47), respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in other secondary outcomes. Four and 8 serious adverse events were self-reported in the standard OMT and sham OMT groups, respectively, though none was considered related to OMT.

The authors concluded that standard OMT had a small effect on LBP-specific activity limitations vs sham OMT. However, the clinical relevance of this effect is questionable.

This study was funded the French Ministry of Health and sponsored by the Département de la Recherche Clinique et du Développement de l’Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris. It is of exceptionally good quality. Its findings are important, particularly in France, where osteopaths have become as numerous as their therapeutic claims irresponsible.

In view of what we have been repeatedly discussing on this blog, the findings of the new trial are unsurprising. Osteopathy is far less well supported by sound evidence than osteopaths want us to believe. This is true, of course, for the plethora of non-spinal claims, but also for LBP. The French authors cite previously published evidence that is in line with their findings: In a systematic review, Rubinstein and colleagues compared the efficacy of manipulative treatment to sham manipulative treatment on LBP-specific activity limitations and did not find evidence of differences at 3 and 12 months (3 RCTs with 573 total participants and 1 RCT with 63 total participants). Evidence was considered low to very low quality. When merging the present results with these findings, we found similar standardized mean difference values at 3months (−0.11 [95% CI, −0.24 to 0.02]) and 12 months (−0.11 [95% CI, −0.33 to 0.11]) (4 RCTs with 896 total participants and 2 RCTs with 320 total participants).

So, what should LBP patients do?

The answer is, as I have often mentioned, simple: exercise!

And what will the osteopaths do?

The answer to this question is even simpler: they will find/invent reasons why the evidence is not valid, ignore the science, and carry on making unsupported therapeutic claims about OMT.

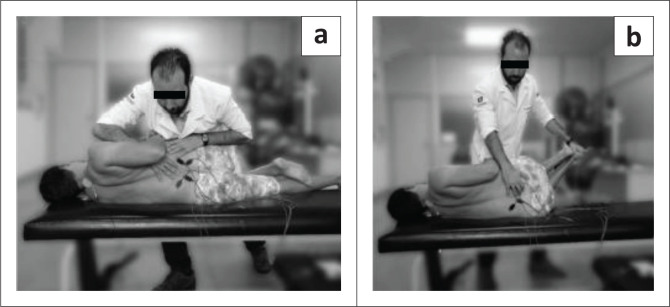

This study compared the effectiveness of two osteopathic manipulative techniques on clinical low back symptoms and trunk neuromuscular postural control in male workers with chronic low back pain (CLBP).

Ten male workers with CLBP were randomly allocated to two groups: high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) manipulation or muscle energy techniques (MET). Each group received one therapy per week for both techniques during 7 weeks of treatment.

Pain and function were measured by using the Numeric Pain-Rating Scale, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. The lumbar flexibility was assessed by Modified Schober Test. Electromyography (EMG) and force platform measurements were used for evaluation of trunk muscular activation and postural balance, respectively at three different times: baseline, post-intervention, and 15 days later.

Both techniques were effective (p < 0.01) in reducing pain with large clinical differences (-1.8 to -2.8) across immediate and after 15 days. However, no significant effect between groups and times was found for other variables, namely neuromuscular activation, and postural balance measures.

The authors concluded that both techniques (HVLA thrust manipulation and MET) were effective in reducing back pain immediately and 15 days later. Neither technique changed the trunk neuromuscular activation patterns nor postural balance in male workers with LBP.

There is, of course, another conclusion that fits the data just as well: both techniques were equally ineffective.

This recent article is truly remarkable:

There is a faction within the chiropractic profession passionately advocating against the routine use of X-rays in the diagnosis, treatment and management of patients with spinal disorders (aka subluxation). These activists reiterate common false statements such as “there is no evidence” for biomechanical spine assessment by X-ray, “there are no guidelines” supporting routine imaging, and also promulgate the reiterating narrative that “X-rays are dangerous.” These arguments come in the form of recycled allopathic “red flag only” medical guidelines for spine care, opinion pieces and consensus statements. Herein, we review these common arguments and present compelling data refuting such claims. It quickly becomes evident that these statements are false. They are based on cherry-picked medical references and, most importantly, expansive evidence against this narrative continues to be ignored. Factually, there is considerable evidential support for routine use of radiological imaging in chiropractic and manual therapies for 3 main purposes: 1. To assess spinopelvic biomechanical parameters; 2. To screen for relative and absolute contraindications; 3. To reassess a patient’s progress from some forms of spine altering treatments. Finally, and most importantly, we summarize why the long-held notion of carcinogenicity from X-rays is not a valid argument.

Not only is low dose radiation not detrimental, but it also protects us from cancer, according to the authors:

Exposures to low-dose radiation incites multiple and multi-hierarchical biopositive mechanisms that prevent, repair or remove damage caused mostly by endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) and H2O2 from aerobic metabolism. Indeed, non-radiogenic (i.e. naturally occurring) molecular damage occurs daily at rates many orders of magnitude greater than the rate of damage caused by low-dose radiation such as diagnostic X-rays. It is estimated that the endogenous genetic damage caused on a daily basis from simply breathing air is about one million times the damage initially resulting from an X-ray. We concur that “it is factually preposterous to have radiophobic cancer concerns from medical X-rays after considering the daily burden of endogenous DNA damage.”

And, of course, radiological imaging makes sense in cases of non-specific back pain due to ‘malalignment’ of the spine:

Pressures to restrict the use of “repeat” (i.e. follow-up) X-rays for assessing patient response to treatment shows a complete disregard for the evidence discussed that definitively illustrates how modern spine rehabilitation techniques and practices successfully re-align the spine and pelvis for a wide variety of presenting subluxation/deformity patterns. The continued anti-X-ray sentiment from “consensus” and opinion within chiropractic needs to stop; it is antithetical to scientific reality and to the practice of contemporary chiropractic practice. We reiterate a quote from the late Michael A. Persinger: “what is happening in recent years is that facts are being defined by consensus. If a group of people think that something is correct, therefore it’s true, and that’s contradictory to science.”

Thus, the authors feel entitled to conclude:

Routine and repeat X-rays in the nonsurgical treatment of patients with spine disorders is an evidence-based clinical practice that is warranted by those that practice spine-altering methods. The evidence supporting such practices is based on definitive evidence supporting the rationale to assess a patient’s spinopelvic parameters for biomechanical diagnosis, to screen for relative and absolute contraindications for specific spine care methods, and to re-assess the spine and postural response to treatment.

The traditional and underlying presumption of the carcinogenicity from X-rays is not a valid notion because the LNT is not valid for low-dose exposures. The ALARA radiation protection principle is obsolete, the threshold for harm is high, low-dose exposures prevent cancers by stimulating and upregulating the body’s innate adaptive protection mechanisms, the TCD concept in invalid, and aged cohort studies assumed to show cancers resulting from previous X-rays are not generalizable to the wider population because they represent populations predisposed to cancers.

Red flags, or suspected serious underlying disease is a valid consideration warranting screening imaging by all spine care providers. We contend, however, that as long as the treating physician or rehabilitation therapist is practicing evidence-based methods, proven to improve spine and postural parameters in order to provide relief for the myriad of spinal disorders, spinal X-rays are unequivocally justified. Non-surgical spine care guidelines need to account for proven and evolving non-surgical methods that are radiographically guided, patient-centered, and competently practiced by those specialty trained in such methods. This is over and above so-called “red flag only” guidelines. The efforts to universally dissuade chiropractors from routine and repeat X-ray imaging is neither scientifically justified nor ethical.

There seems to be just one problem here: the broad consensus is against almost anything these authors claim.

Oh, I almost forgot: this paper was authored and sponsored by CBP NonProfit.

“The mission of Chiropractic BioPhysics® (CBP®) Non-Profit is to provide a research based response to these changing times that is clinically, technically, and philosophically sound. By joining together, we can participate in the redefinition and updating of the chiropractic profession through state of the art spine research efforts. This journey, all of us must take as a Chiropractic health care profession to become the best we can be for the sake of the betterment of patient care. CBP Non-Profit’s efforts focus on corrective Chiropractic care through structural rehabilitation of the spine and posture. Further, CBP Non-Profit, Inc. has in its purpose to fund Chiropractic student scholarships where appropriate as well as donate needed chiropractic equipment to chiropractic colleges; always trying to support chiropractic advancement and education.”

This systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed at investigating the effect and safety of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic spinal pain.

The authors included 22 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving patients with chronic spinal pain treated by acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, no treatment, or another treatment were included. Chronic spinal pain was defined as:

- chronic neck pain,

- chronic low back pain,

- or sciatica for more than 3 months.

Fourteen studies had a high risk of bias, 5 studies had a low risk of bias, and 5 studies had an unclear risk of bias. Pooled analysis revealed that:

- acupuncture can reduce chronic spinal pain compared to sham acupuncture (weighted mean difference [WMD] -12.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] -15.86 to -8.24),

- acupuncture can reduce chronic spinal pain compared to mediation control (WMD -18.27, 95% CI -28.18 to -8.37),

- acupuncture can reduce chronic spinal pain compared to usual care control (WMD -9.57, 95% CI -13.48 to -9.44),

- acupuncture can reduce chronic spinal pain compared to no treatment control (WMD -17.10, 95% CI -24.83 to -9.37).

In terms of functional disability, acupuncture can improve physical function at

- immediate-term follow-up (standardized mean difference [SMD] -1.74, 95% CI -2.04 to -1.44),

- short-term follow-up (SMD -0.89, 95% CI -1.15 to -0.62),

- long-term follow-up (SMD -1.25, 95% CI -1.48 to -1.03).

Trials assessed as having a high risk of bias (WMD −13.45, 95% CI −17.23 to −9.66, I 2 96.2%, moderate-quality evidence, including 14 studies and 1379 patients) found greater effects of acupuncture treatment than trials assessed as having a low risk of bias (WMD −11.99, 95% CI −13.94 to −10.03, I 2 44.6%, high-quality evidence, including 4 studies and 432 patients), but smaller effects than trials assessed as having an unclear risk of bias (WMD −14.51, 95% CI −17.25 to −11.78, I 2 0%, high-quality evidence, including 3 studies and 190 patients).

Only 6 trials provided information on adverse events. No trial reported data on serious adverse events during acupuncture treatment. The most frequent adverse events were temporarily worsened pain and needle pain at the acupuncture site, which can decrease quickly after a short period of rest.

The authors concluded that compared to no treatment, sham acupuncture, or conventional therapy such as medication, massage, and physical exercise, acupuncture has a significantly superior effect on the reduction in chronic spinal pain and function improvement. Acupuncture might be an effective treatment for patients with chronic spinal pain and it is a safe therapy.

I think this is a thorough review which produced interesting findings. I agree with most of what the authors report, except with their conclusions which I find too optimistic. In view of the facts that

- only 5 RCTs had a low risk of bias,

- collectively, the rigorous trials reported smaller effect sizes,

- the majority of trials failed to mention adverse effects which, in my view, casts considerable doubt on their quality and ethical standard,

I would have phrased the conclusion differently: compared to no treatment, sham acupuncture, or conventional therapies, acupuncture seems to have a significantly superior effect on pain and function. Due to the lack rigour of most studies, these effects are less certain than one would have wished. Many trials fail to report adverse effects which reflects poorly on their quality and ethics and prevents conclusions about the safety of acupuncture. In essence, this means that the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture as a treatment of chronic spinal pain remains uncertain.

Low-level laser therapy has been used clinically to treat musculoskeletal pain; however, there is limited evidence available to support its use. The current Cochrance review fails to be positive: there are insufficient data to draw firm conclusions on the clinical effect of LLLT for low‐back pain. So, perhaps studies on animals generate clearer answers?

The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of low-level laser therapy and chiropractic care in treating thoracolumbar pain in competitive western performance horses. The subjects included 61 Quarter Horses actively involved in national western performance competitions judged to have back pain. A randomized, clinical trial was conducted by assigning affected horses to either:

- laser therapy,

- chiropractic,

- or combined laser and chiropractic treatment groups.

Low-level laser therapy was applied topically to local sites of back pain. The laser probe contained four 810-nm laser diodes spaced 15-mm apart in a square array that produced a total optical output power of 3 watts. Chiropractic treatment was applied to areas of pain and stiffness within the thoracolumbar and sacral regions. A single application of a high velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) manual thrust was applied to affected vertebral segments using a reinforced hypothenar contact and a body-centered, body-drop technique. The HVLA thrusts were directed dorsolateral to ventromedial (at a 45° angle to the horizontal plane) with a segmental contact near the spinous process with the goal of increasing extension and lateral bending within the adjacent vertebral segments. If horses did not tolerate the applied chiropractic treatment, then truncal stretching, spinal mobilization, and the use of a springloaded, mechanical-force instrument were used as more conservative forms of manual therapy in these acute back pain patients.

Outcome parameters included a visual analog scale (VAS) of perceived back pain and dysfunction and detailed spinal examinations evaluating pain, muscle tone, and stiffness. Mechanical nociceptive thresholds were measured along the dorsal trunk and values were compared before and after treatment. Repeated measures with post-hoc analysis were used to assess treatment group differences.

Low-level laser therapy, as applied in this study, produced significant reductions in back pain, epaxial muscle hypertonicity, and trunk stiffness. Combined laser therapy and chiropractic care produced similar reductions, with additional significant decreases in the severity of epaxial muscle hypertonicity and trunk stiffness. Chiropractic treatment by itself did not produce any significant changes in back pain, muscle hypertonicity, or trunk stiffness; however, there were improvements in trunk and pelvic flexion reflexes.

The authors concluded that the combination of laser therapy and chiropractic care seemed to provide additive effects in treating back pain and trunk stiffness that were not present with chiropractic treatment alone. The results of this study support the concept that a multimodal approach of laser therapy and chiropractic care is beneficial in treating back pain in horses involved in active competition.

Let me play the devil’s advocate and offer a different conclusion:

These results show that horses are not that different from humans when it comes to responding to treatments. One placebo has a small effect; two placebos generate a little more effects.

Manual therapy is a commonly recommended treatment of low back pain (LBP), yet few studies have directly compared the effectiveness of thrust (spinal manipulation) vs non-thrust (spinal mobilization) techniques. This study evaluated the comparative effectiveness of spinal manipulation and spinal mobilization at reducing pain and disability compared with a placebo control group (sham cold laser) in a cohort of young adults with chronic LBP.

This single-blinded (investigator-blinded), placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial with 3 treatment groups was conducted at the Ohio Musculoskeletal and Neurological Institute at Ohio University from June 1, 2013, to August 31, 2017. Of 4903 adult patients assessed for eligibility, 4741 did not meet inclusion criteria, and 162 patients with chronic LBP qualified for randomization to 1 of 3 treatment groups. Participants received 6 treatment sessions of (1) spinal manipulation, (2) spinal mobilization, or (3) sham cold laser therapy (placebo) during a 3-week period. Licensed clinicians (either a doctor of osteopathic medicine or physical therapist), with at least 3 years of clinical experience using manipulative therapies provided all treatments.

Primary outcome measures were the change from baseline in Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) score over the last 7 days and the change in disability assessed with the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater disability) 48 to 72 hours after completion of the 6 treatments.

A total of 162 participants (mean [SD] age, 25.0 [6.2] years; 92 women [57%]) with chronic LBP (mean [SD] NPRS score, 4.3 [2.6] on a 1-10 scale, with higher scores indicating greater pain) were randomized.

- 54 participants were randomized to the spinal manipulation group,

- 54 to the spinal mobilization group,

- 54 to the placebo group.

There were no significant group differences for sex, age, body mass index, duration of LBP symptoms, depression, fear avoidance, current pain, average pain over the last 7 days, and self-reported disability. At the primary end point, there was no significant difference in change in pain scores between spinal manipulation and spinal mobilization (0.24 [95% CI, -0.38 to 0.86]; P = .45), spinal manipulation and placebo (-0.03 [95% CI, -0.65 to 0.59]; P = .92), or spinal mobilization and placebo (-0.26 [95% CI, -0.38 to 0.85]; P = .39). There was no significant difference in change in self-reported disability scores between spinal manipulation and spinal mobilization (-1.00 [95% CI, -2.27 to 0.36]; P = .14), spinal manipulation and placebo (-0.07 [95% CI, -1.43 to 1.29]; P = .92) or spinal mobilization and placebo (0.93 [95% CI, -0.41 to 2.29]; P = .17). A comparison of treatment credibility and expectancy ratings across groups was not statistically significant (F2,151 = 1.70, P = .19), indicating that, on average, participants in each group had similar expectations regarding the likely benefit of their assigned treatment.

The authors concluded that in this randomized clinical trial, neither spinal manipulation nor spinal mobilization appeared to be effective treatments for mild to moderate chronic LBP.

This is an exceptionally well-reported study. Yet, one might raise a few points of criticism:

- The comparison of two active treatments makes this an equivalence study, and much larger sample sizes are required or such trials (this does not mean that the comparisons are not valid, however).

- The patients had rather mild symptoms; one could argue that patients with severe pain might respond differently.

- Chiropractors could argue that the therapists were not as expert at spinal manipulation as they are; had they employed chiropractic therapists, the results might have been different.

- A placebo control group makes more sense, if it allows patients to be blinded; this was not possible in this instance, and a better placebo might have produced different findings.

Despite these limitations, this study certainly is a valuable addition to the evidence. It casts more doubt on spinal manipulation and mobilisation as an effective therapy for LBP and confirms my often-voiced view that these treatments are not the best we can offer to LBP-patients.