alternative medicine

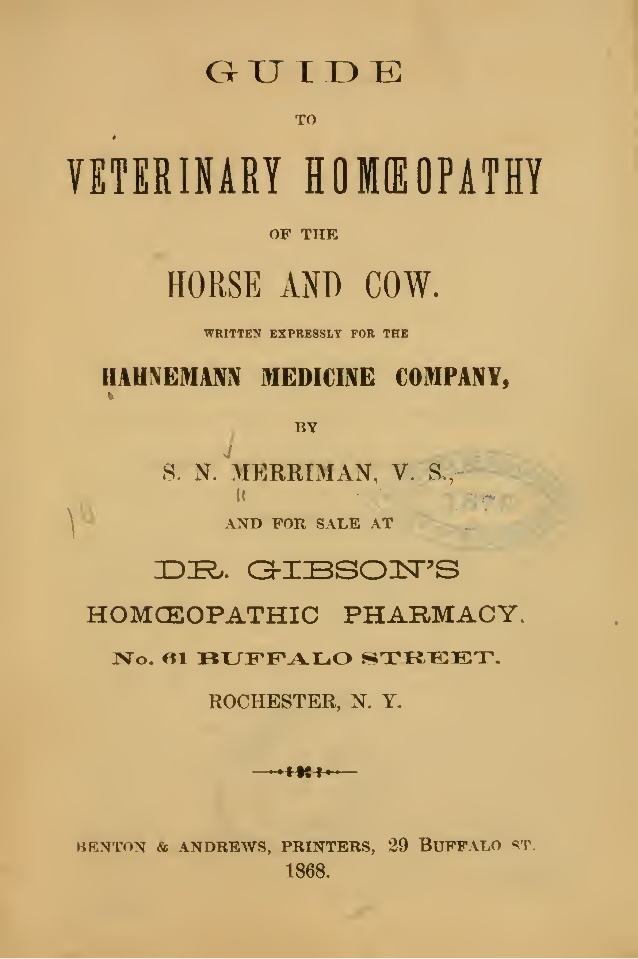

Ever since Samuel Hahnemann, the German physician who invented homeopathy, gave a lecture on the subject in the mid-1810s, homeopathy has been used for treating animals. Initially, veterinary medical schools tended to reject homoeopathy as implausible, and the number of veterinary homeopaths remained small. In the 1920ies, however, veterinary homoeopathy was revived in Germany, and in 1936, members of the “Studiengemeinschaft für tierärztliche Homöopathie” (Study Group for Veterinary Homoeopathy) started to investigate homeopathy systematically.

Today, veterinary homeopathy is popular not least because of the general boom in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Prince Charles is just one of many prominent advocates who claims to treat animals with homeopathy. In many countries, veterinary homeopaths have their own professional organisations, while elsewhere veterinarians are banned from practicing homeopathy. In the UK, only veterinarians are currently allowed to use homeopathy on animals (but ironically, anyone regardless of background can use it on human patients).

Considering the implausibility of its assumptions, it seems unlikely that homeopathic remedies can be anything other than placebos. Yet homeopaths and their followers regularly produce clinical trials that seem to suggest efficacy. Today, there are about 500 controlled clinical trials of homeopathy (mostly on humans), and it is no surprise that, purely by chance, some of them show positive results. To avoid being misled by random findings, cherry-picking, or flawed science, we ought to critically evaluate the totality of the available evidence. In other words, we should rely not on single studies but on systematic reviews of all reliable trials.

A 2015 systematic review by ardent homeopaths tested the hypothesis that the outcome of veterinary homeopathic treatments is distinguishable from placebos. A total of 15 trials could be included, but only two comprised reliable evidence without overt vested interest. The authors concluded that there is “very limited evidence that clinical intervention in animals using homeopathic medicines is distinguishable from corresponding intervention using placebos.”

A more recent systematic review compared the efficacy of homeopathy to that of antibiotics in cattle, pigs and poultry. A total number of 52 trials were included of which 28 were in favour of homeopathy and 22 showed no effect. No study had been independently replicated. The authors concluded that “the use of homeopathy cannot claim to have sufficient prognostic validity where efficacy is concerned.”

Discussing this somewhat unclear and contradictory findings of trials of homeopathy for animals, Lee et al concluded that “…it is overwhelmingly likely that small effects observed in the RCTs and systematic reviews are the result of residual bias in the trials.” To this, I might add that ‘publication bias’, i. e. the phenomenon that negative trials often remain unpublished, might be the reason why systematic reviews of homeopathy are never entirely negative.

In recent years, several scientific bodies have assessed the evidence on homeopathy and published statements about it. Here are the key passages from some of these ‘official verdicts’:

“The principles of homeopathy contradict known chemical, physical and biological laws and persuasive scientific trials proving its effectiveness are not available”

Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia

“Homeopathy should not be used to treat health conditions that are chronic, serious, or could become serious. People who choose homeopathy may put their health at risk if they reject or delay treatments for which there is good evidence for safety and effectiveness.”

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia

“These products are not supported by scientific evidence.”

Health Canada, Canada

“Homeopathic remedies don’t meet the criteria of evidence-based medicine.”

Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary

“The incorporation of anthroposophical and homeopathic products in the Swedish directive on medicinal products would run counter to several of the fundamental principles regarding medicinal products and evidence-based medicine.”

Swedish Academy of Sciences, Sweden

“There is little evidence to support homeopathy as an effective treatment for any specific condition”

National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health, USA

“There is no good-quality evidence that homeopathy is effective as a treatment for any health condition”

“Homeopathic remedies perform no better than placebos, and the principles on which homeopathy is based are “scientifically implausible””

House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, UK

“Homeopathy has not definitively proven its efficacy in any specific indication or clinical situation.”

Ministry of Health, Spain

“… homeopathy should be treated as one of the unscientific methods of the so called ‘alternative medicine’, which proposes worthless products without scientifically proven efficacy.”

National Medical Council, Poland

“… there is no valid empirical proof of the efficacy of homeopathy beyond the placebo effect.”

Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg, Belgium

As they are usually far too dilute to contain anything, homeopathic remedies are generally harmless, provided they are produced according to good manufacturing practice (which is not always the case). Unfortunately, however, this harmlessness does not necessarily apply to homeopathy in general. When employed to replace an effective therapy, even the most innocent but ineffective treatment can become life-threatening. Since homeopaths recommend their remedies for even the most serious conditions, this is by no means a theoretical consideration. I have therefore often stated that HOMEOPATHICS MIGHT BE HARMLESS, BUT HOMEOPATHS CERTAINLY ARE NOT.

It follows that an independent risk/benefit analysis of homeopathy fails to arrive at a positive conclusion. In other words, homeopathy has not been shown to generate more good than harm. In turn, this means that homeopathy has no place in veterinary (or human) evidence-based medicine.

Determined to cover as many so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs) as I possibly can, I was intrigued to see an article in the EVENING STANDARD about a SCAM I had not been familiar with: YANG SHENG.

Here is an excerpt of this article:

When people meet Katie Brindle, they usually ask whether she does acupuncture. “In fact, I specialise in yang sheng,” she says, a sigh in her voice. “It’s a massive aspect of Chinese medicine that no one knows anything about.” She’s on a mission to change that. Yang sheng is, in simplest terms, “prevention not cure” and Brindle puts it into practice with Hayo’u, her part-beauty brand, part-wellness programme, which draws on rituals in Far Eastern medicine. The “Reset” ritual, for example, is based on the Chinese martial art of qigong and involves shaking, drumming and twisting the body to wake up your circulation — Brindle says it stimulates digestion and boosts immunity. The “Body Restorer”, a gentle massage of the neck, chest and back, has a history of being used as a form of treatment for fever, muscle pain, inflammation and migraines. The principle underpinning all the practices is that small changes in your daily routine can help prevent your body from illness. Brindle wants it to be accessible: the website is free, and she is planning Facebook live-streams later in the year. There will also be a book in April, focusing on prevention rather than cure…

Frustrated about the overtly adversorial nature of this article, I did a few searches (not made easy by the fact that Yang and Sheng are common names of authors and yangsheng is the name of an acupuncture point) and found that Yang Sheng is said to be a health-promoting method in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) that includes movement, mental exercise, and breathing technique. It is used mainly in China but has apparently it is currently enjoying an ever-widening acceptance in the Western world as well.

Is there any evidence for it?

Good question!

A paper from 1998 reported an observational study with 30 asthma patients, with varying degrees of illness severity. They were taught Qigong Yangsheng under medical supervision and asked to exercise independently, if possible, on a daily basis. They kept a diary of their symptoms for half a year including peak-flow measurements three times daily, use of medication, frequency and length of exercise as well as five asthma-relevant symptoms (sleeping through the night, coughing, expectoration, dyspnea, and general well-being). A decrease of at least 10 percent in peak-flow variability between the 1st and the 52nd week occurred more frequently in the group of the exercisers (n = 17) than in the group of non-exercisers (n = 13). When comparing the study year with the year before the study, there was improvement also in reduced hospitalization rate, less sickness leave, reduced antibiotic use and fewer emergency consultations resulting in reduced treatment costs. The authors concluded that Qigong Yangsheng is recommended for asthma patients with professional supervision. An improvement in airway capability and a decrease in illness severity can be achieved by regular self-conducted Qigong exercises.

The flaws of this study are obvious, and I don’t even bother to criticise it here.

Unfortunately, that was the only ‘study’ I found.

I also located many websites most of which are all but useless. Here is one that offers some explanations:

Yang sheng is a self-care approach. What makes this any different from all those other wellbeing manuals? The short answer is, that this is advice rooted in thousands of years of wisdom. Texts on how to preserve and extend life, health and wellbeing have been part of the Chinese tradition since the 4thcentury BC. They’ve had over 25 centuries to be refined and are time tested.

Yang sheng takes into account core theories like yin and yang, adhering to the laws of nature and harmonious free flow of Qi around the body (see below). As the active pursuit of the best possible functioning and balance of the whole self – body, mind and spirit. Yang Sheng takes into consideration your relationships to people and the environment.

In the West, we systematically neglect wellness and disease prevention. We take our good health for granted. We assume that we cannot avoid disease. And then when we are ill, we treat the symptoms of disease rather than finding the root cause.

Yang Sheng is about discovering energy imbalances long before they turn into overt disease. It works on the approach of eliminating small health niggles and balancing the body to stay healthy.

If this sounds like a conspiracy of BS to you, I would not blame you.

So, what can we conclude from this? I think, it is fair to say that:

- Yang Sheng is being promoted as yet another TCM miracle.

- It is based on all the obsolete nonsense that TCM has to offer.

- Numerous therapeutic and preventative claims are being made for it.

- None of them is supported by anything resembling good evidence.

- Anyone with a serious condition who trusts Yang Sheng advocates puts her/his life in danger.

- The EVENING STANDARD is not a source for reliable medical information.

I don’t expect many of my readers to be surprised, concerned or alarmed by any of this. In my view, however, this lack of alarm is exactly what is alarming! We have become so used to seeing bogus claims and dangerous BS in the realm of SCAM that abnormality has gradually turned into something close to normality.

I find the type of normality that incessantly misleads consumers and endangers patients quite simply unacceptable.

Pertussis (whooping-cough) is a serious condition. Today, we have vaccinations and antibiotics against it and therefore it is rarely a fatal disease. A century or so, the situation was different. Then all sorts of quacks claimed to be able to treat pertussis and many patients, particularly children, died.

This article starts with this amazing introduction: Osteopathic physicians may want to consider using osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) as an adjunctive treatment modality for pertussis; however, suitable OMT techniques are not specified in the research literature.

For the paper, the author then searched the historical osteopathic literature to identify OMT techniques that were used in the management of pertussis in the pre-antibiotic era. The 24 identified sources included 8 articles and 16 book contributions from the years 1886 to 1958. Most sources were published within the first quarter of the 20th century. Commonly identified OMT techniques included mobilization techniques, lymphatic pump techniques, and other manipulative techniques predominantly in the cervical and thoracic regions.

The author concluded that the wealth of OMT techniques for patients with pertussis that were identified suggests that pertussis was commonly treated by early osteopaths. Further research is necessary to identify or establish the evidence base for these techniques so that in case of favorable outcomes, their use by osteopathic physicians is justified as adjunctive modalities when encountering a patient with pertussis.

I found it hard to decide whether to laugh or to cry after reading this. One could easily have a good giggle about the silliness of the idea to revive obsolete techniques for treating a potentially serious infection. One the other hand, I cannot help but ask myself:

- Is there any suggestion at all that OMT was successful in treating pertussis?

- If the answer is negative (and I fear it is), why would anyone spend considerable resources to establish the evidence base for these techniques?

- Do osteopaths believe in progress at all?

- Do they really think that there is even a remote chance that mobilization techniques, lymphatic pump techniques, and other manipulative techniques will, one day, come back as adjunctive therapies for pertussis?

- Do they not believe in a rational approach to prioritising medical research such that scarce resources are spent ethically and wisely?

You may think that none of this really matters. The author of this paper is just a lone loon! That may well be so, but even lone loons can do a lot of harm, if they convince consumers of their bizarre ideas.

But surely, the profession of osteopathy would not tolerate this, you say. I am not convinced. The article was published in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. This seems significant to me. It is comparable to the JAMA or the BMJ publishing an article calling for a programme of research into the possible benefits of blood-letting as a treatment of pneumonia!

Acupuncture is all over the news today. The reason is a study just out in BMJ-Open.

The aim of this new RCT was to investigate the efficacy of a standardised brief acupuncture approach for women with moderate-tosevere menopausal symptoms. Nine Danish primary care practices recruited 70 women with moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms. Nine general practitioners with accredited education in acupuncture administered the treatments.

The acupuncture style was western medical with a standardised approach in the pre-defined acupuncture points CV-3, CV-4, LR-8, SP-6 and SP-9. The intervention group received one treatment for five consecutive weeks. The control group received no acupuncture but was offered treatment after 6 weeks. Outcomes were the differences between the two groups in changes to mean scores using the scales in the MenoScores Questionnaire, measured from baseline to week 6. The primary outcome was the hot flushes scale; the secondary outcomes were the other scales in the questionnaire. All analyses were based on intention-to-treat analysis.

Thirty-six patients received the intervention, and 34 were in the control group. Four participants dropped out before week 6. The acupuncture intervention significantly decreased hot flushes, day-and-night sweats, general sweating, menopausal-specific sleeping problems, emotional symptoms, physical symptoms and skin and hair symptoms compared with the control group at the 6-week follow-up. The pattern of decrease in hot flushes, emotional symptoms, skin and hair symptoms was already apparent three weeks into the study. Mild potential adverse effects were reported by four participants, but no severe adverse effects were reported.

The authors concluded that the standardised and brief acupuncture treatment produced a fast and clinically relevant reduction in moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms during the six-week intervention.

The only thing that I find amazing here is the fact the a reputable journal published such a flawed trial arriving at such misleading conclusions.

- The authors call it a ‘pragmatic’ trial. Yet it excluded far too many patients to realistically qualify for this characterisation.

- The trial had no adequate control group, i.e. one that can account for placebo effects. Thus the observed outcomes are entirely in keeping with the powerful placebo effect that acupuncture undeniably has.

- The authors nevertheless conclude that ‘acupuncture treatment produced a fast and clinically relevant reduction’ of symptoms.

- They also state that they used this design because no validated sham acupuncture method exists. This is demonstrably wrong.

- In my view, such misleading statements might even amount to scientific misconduct.

So, what would be the result of a trial that is rigorous and does adequately control for placebo-effects? Luckily, we do not need to rely on speculation here; we have a study to demonstrate the result:

Background: Hot flashes (HFs) affect up to 75% of menopausal women and pose a considerable health and financial burden. Evidence of acupuncture efficacy as an HF treatment is conflicting.

Objective: To assess the efficacy of Chinese medicine acupuncture against sham acupuncture for menopausal HFs.

Design: Stratified, blind (participants, outcome assessors, and investigators, but not treating acupuncturists), parallel, randomized, sham-controlled trial with equal allocation. (Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12611000393954)

Setting: Community in Australia.

Participants: Women older than 40 years in the late menopausal transition or postmenopause with at least 7 moderate HFs daily, meeting criteria for Chinese medicine diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency.

Interventions:10 treatments over 8 weeks of either standardized Chinese medicine needle acupuncture designed to treat kidney yin deficiency or noninsertive sham acupuncture.

Measurements: The primary outcome was HF score at the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, anxiety, depression, and adverse events. Participants were assessed at 4 weeks, the end of treatment, and then 3 and 6 months after the end of treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted with linear mixed-effects models.

Results: 327 women were randomly assigned to acupuncture (n = 163) or sham acupuncture (n = 164). At the end of treatment, 16% of participants in the acupuncture group and 13% in the sham group were lost to follow-up. Mean HF scores at the end of treatment were 15.36 in the acupuncture group and 15.04 in the sham group (mean difference, 0.33 [95% CI, −1.87 to 2.52]; P = 0.77). No serious adverse events were reported.

Limitation: Participants were predominantly Caucasian and did not have breast cancer or surgical menopause.

Conclusion: Chinese medicine acupuncture was not superior to noninsertive sham acupuncture for women with moderately severe menopausal HFs.

My conclusion from all this is simple: acupuncture trials generate positive findings, provided the researchers fail to test it rigorously.

Did we not have a flurry of systematic reviews of homeopathy in recent months?

And were they not a great disappointment to homeopaths and their patients?

Just as we thought that this is more than enough evidence to show that homeopathy is not effective, here comes another one.

This new review evaluated RCTs of non-individualised homeopathic treatment (NIHT) in which the control group received treatments other than placebo (OTP). Specifically, its aim was to determine the comparative effectiveness of NIHT on health-related outcomes for any given condition.

For each eligible trial, published in the peer-reviewed literature up to the end of 2016, the authors assessed its risk of bias (internal validity) using the seven-domain Cochrane tool, and its relative pragmatic or explanatory attitude (external validity) using the 10-domain PRECIS tool. The researchers grouped RCTs by whether these examined homeopathy as an alternative treatment (study design 1a), adjunctively with another intervention (design 1b), or compared with no intervention (design 2). RCTs were sub-categorised as superiority trials or equivalence/non-inferiority trials. For each RCT, a single ‘main outcome measure’ was selected to use in meta-analysis.

Seventeen RCTs, representing 15 different medical conditions, were eligible for inclusion. Three of the trials were more pragmatic than explanatory, two were more explanatory than pragmatic, and 12 were equally pragmatic and explanatory. Fourteen trials were rated ‘high risk of bias’ overall; the other three trials were rated ‘uncertain risk of bias’ overall. Ten trials had data that were extractable for meta-analysis. Significant heterogeneity undermined the planned meta-analyses or their meaningful interpretation. For the three equivalence or non-inferiority trials with extractable data, the small, non-significant, pooled effect size was consistent with a conclusion that NIHT did not differ from treatment by a comparator (Ginkgo biloba or betahistine) for vertigo or (cromolyn sodium) for seasonal allergic rhinitis.

The authors concluded that the current data preclude a decisive conclusion about the comparative effectiveness of NIHT. Generalisability of findings is restricted by the limited external validity identified overall. The highest intrinsic quality was observed in the equivalence and non-inferiority trials of NIHT.

I do admire the authors’ tenacity in meta-analysing homeopathy trials and empathise with their sadness of the multitude of negative results they thus have to publish. However, I do disagree with their conclusions. In my view, at least two firm conclusions ARE possible:

- This dataset confirms yet again that the methodological quality of homeopathy trials is lousy.

- The totality of the trial evidence analysed here fails to show that non-individualised homeopathy is effective.

In case you wonder why the authors are not more outspoken about their own findings, perhaps you need to read their statement of conflicts of interest:

Authors RTM, YYYF, PV and AKLT are (or were) associated with a homeopathy organisation whose significant aim is to clarify and extend an evidence base in homeopathy. RTM holds an independent research consultancy contract with the Deutsche Homöopathie-Union, Karlsruhe, Germany. YYYF and AKLT belong to Living Homeopathy Ltd., which has contributed funding to some (but not this current) HRI project work. RTM and PV have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. JRTD had no support from any organisation for the submitted work; in the last 3 years, and for activities outside the submitted study, he received personal fees, royalties or out-of-pocket expenses for advisory work, invitational lectures, use of rating scales, published book chapters or committee membership; he receives royalties from Springer Publishing Company for his book, A Century of Homeopaths: Their Influence on Medicine and Health. JTRD has no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted study.

If one had wanted to add insult to injury, one could have added that, if, despite such conflicts of interest, the overall result of this new review turned out to be not positive, the evidence must be truly negative.

In 2004, my team published a review analysing the diversity of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) research published in one single year (2002) across 7 European countries (Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, France, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium) and the US. In total 652 abstracts of articles were assessed. Germany and the UK were the only two European countries to publish in excess of 100 articles in that year (Germany: 137, UK: 183). The majority of articles were non-systematic reviews and comments, analytical studies and surveys. The UK carried out more surveys than any of the other countries and also published the largest number of systematic reviews. Germany, the UK and the US covered the widest range of interests across various SCAM modalities and investigated the safety of CAM. We concluded that important national differences exist in terms of the nature of SCAM research. This raises important questions regarding the reasons for such differences.

One striking difference was the fact that, compared to the UK, Germany had published far less research on SCAM that failed to report a positive result (4% versus 14%). Ever since, I have wondered why. Perhaps it has something to do with the biggest sponsor of SCAM research in Germany: THE CARSTENS STIFTUNG?

The Carstens Foundation (CF) was created by the former German President, Prof. Dr. Karl Carstens and his wife, Dr. Veronica Carstens. Karl Carstens (1914-1992) was the 5th President of federal Germany, from 1979 to 1984. Veronica Carstens (1923-2012) was a doctor of Internal Medicine with an interest in natural medicine and homeopathy in particular. She is quoted by the CF stating: „Der Arzt und die Ärztin der Zukunft sollen zwei Sprachen sprechen, die der Schulmedizin und die der Naturheilkunde und Homöopathie. Sie sollen im Einzelfall entscheiden können, welche Methode die besten Heilungschancen für den Patienten bietet.“ (Future doctors should speak two languages, that of ‘school medicine’ [Hahnemann’s derogatory term for conventional medicine] and that of naturopathy and homeopathy. They should be able to decide on a case by case basis which method offers the best chances of a cure for the patient.***)

Together, the two Carstens created the CF with the goal of sponsoring SCAM in Germany. More than 35 million € have so far been spent on more than 100 projects, fellowships, dissertations, an own publishing house, and a patient society “Natur und Medizin” (currently ~23 000 members) with the task of promoting SCAM. Projects the CF proudly list as their ‘milestones’ include:

- an outpatient clinic of natural medicine for cancer

- a project ‘Natural medicine and homeopathy for children and adolescents’.

The primary focus of the CF clearly is homeopathy, and it is in this area where their anti-science bias gets most obvious. I do invite everyone who reads German to have a look at their website and be amazed at the plethora of misleading claims.

Their expert for all things homeopathic is Dr Jens Behnke (‘Referent für Homöopathieforschung bei der Karl und Veronica Carstens-Stiftung: Evidenzbasierte Medizin, CAM, klinische Forschung, Grundlagenforschung’). He is not a medical doctor but has a doctorate from the ‘Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Europa-Universität Viadrina’ entitled ‘Wissenschaft und Weltanschauung. Eine epistemologische Analyse des Paradigmenstreits in der Homöopathieforschung’ (Science and world view. An epistemological analysis of the paradigm-quarrel in homeopathy research). His supervisor was Prof Harald Walach who has long been close to the CF.

Behnke claims to be an expert in EBM, clinical research and basic research but, intriguingly, he has not a single Medline-listed publication to his name. So, we only have his dissertation to assess his expertise.

The very 1st sentence of his dissertation is noteworthy, in my view: Die Homöopathie ist eine Therapiemethode, die seit mehr als 200 Jahren praktiziert wird und eine beträchtliche Zahl an Heilungserfolgen vorzuweisen hat (Homeopathy is a therapeutic method, that is being used since more than 200 years and which is supported by a remarkable number of therapeutic successes). In essence, the dissertation dismisses the scientific approach for evaluating homeopathy as well as the current best evidence that shows homeopathy to be ineffective.

Behnke dismisses my own research on homeopathy without even considering it. He first claims to have found an error in one of my systematic reviews and then states: Die Fragwürdigkeit der oben angeführten Methoden rechtfertigt das Übergehen sämtlicher Publikationen dieses Autors im Rahmen dieser Arbeit. Wenn einem Wissenschaftler die aufgezeigte absichtliche Falschdarstellung aufgrund von Voreingenommenheit nachgewiesen werden kann, sind seine Ergebnisse, wenn überhaupt, nur nach vorheriger systematischer Überprüfung sämtlicher Originalpublikationen und Daten, auf die sie sich beziehen, verwertbar. Essentially, he claims that, because he has found one error, the rest cannot be trusted and therefore he is entitled to reject the lot.

In the same dissertation, we read the following: Ernst konstatiert in allen … Arbeiten zur Homöopathie ausnahmslos, dass es keinerlei belastbare Hinweise auf eine Wirksamkeit homöopathischer Arzneimittel über Placeboeffekte hinaus gebe (Ernst states in all publications on homeopathy without exception that no solid suggestions exist at all for an effectiveness of homeopathic remedies). However, it is demonstrably wrong that all of my papers arrive at a negative judgement of homeopathy’s effectiveness; here are three that spring into my mind:

- There is evidence that homeopathic treatment can reduce the duration of ileus after abdominal or gynecologic surgery. However, several caveats preclude a definitive judgment. These results should form the basis of a randomized controlled trial to resolve the issue.

- Subjective complaints were relieved significantly more by Poikiven than by placebo. [Poikiven is a homeopathic remedy containing undiluted herbal ingredients, I hasten to add]

- … homeopathy works for certain conditions and is ineffective for others. [yes, I know! … (published in 1990)]

So, applying Behnke’s own logic outlined above, one should argue that, because I have found one error in his research, the rest of what Behnke will (perhaps one day be able to) publish cannot be trusted and therefore I am entitled to reject the lot.

That would, of course, be tantamount to adopting the stupidity of one’s own opponents. So, I will certainly not do that; instead, I will wait patiently for the sound science that Dr Behnke (and indeed the CF) might eventually produce.

***phraseology that is strikingly similar to that of Rudolf Hess on the same subject.

The Journal of Experimental Therapeutics and Oncology states that it is devoted to the rapid publication of innovative preclinical investigations on therapeutic agents against cancer and pertinent findings of experimental and clinical oncology. In the journal you will find review articles, original articles, and short communications on all areas of cancer research, including but not limited to preclinical experimental therapeutics; anticancer drug development; cancer biochemistry; biotechnology; carcinogenesis; cancer cytogenetics; clinical oncology; cytokine biology; epidemiology; molecular biology; pathology; pharmacology; tumor cell biology; and experimental oncology.

After reading an article entitled ‘How homeopathic medicine works in cancer treatment: deep insight from clinical to experimental studies’ in its latest issue, I doubt that the journal is devoted to anything.

Here is the abstract:

In the current scenario of medical sciences, homeopathy, the most popular system of therapy, is recognized as one of the components of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) across the world. Despite, a long debate is continuing whether homeopathy is just a placebo or more than it, homeopathy has been considered to be safe and cost-effectiveness therapeutic modality. A number of human ailments ranging from common to serious have been treated with homeopathy. However, selection of appropriate medicines against a disease is cumbersome task as total spectrum of symptoms of a patient guides this process. Available data suggest that homeopathy has potency not only to treat various types of cancers but also to reduce the side effects caused by standard therapeutic modalities like chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery. Although homeopathy has been widely used for management of cancers, its efficacy is still under question. In the present review, the anti-cancer effect of various homeopathic drugs against different kinds of cancers has been discussed and future course of action has also been suggested.

I do wonder what possessed the reviewers of this paper and the editors of the journal to allow such dangerous (and badly written) rubbish to get published. Do they not know that:

- homeopathy is a placebo therapy,

- homeopathy can not cure any cancer,

- cancer patients are highly vulnerable to false hope,

- such an article endangers the lives of many cancer patients,

- they have an ethical, moral and possibly legal duty to prevent such mistakes?

What makes this paper even more upsetting is the fact that one of its authors is affiliated with the Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

Family welfare my foot!

This certainly is one of the worst violations of healthcare and publication ethic that I have come across for a long time.

Robert Verkerk, Executive & scientific director, Alliance for Natural Health (ANH), seems to adore me (maybe that’s why I kept this post for Valentine’s Day?). In 2006, he published this article about me (it is lengthy, and I therefore shortened a bit, but feel free to study it in its full beauty):

START OF QUOTE

PROFESSOR EDZARD ERNST, the UK’s first professor of complementary medicine, gets lots of exposure for his often overtly negative views on complementary medicine. He’s become the media’s favourite resource for a view on this controversial subject…

The interesting thing about Prof Ernst is that he seems to have come a long way from his humble beginnings as a recipient of the therapies that he now seems so critical of. Profiled by Geoff Watts in the British Medical Journal, the Prof tells us: ‘Our family doctor in the little village outside Munich where I grew up was a homoeopath. My mother swore by it. As a kid I was treated homoeopathically. So this kind of medicine just came naturally. Even during my studies I pursued other things like massage therapy and acupuncture. As a young doctor I had an appointment in a homeopathic hospital, and I was very impressed with its success rate. My boss told me that much of this success came from discontinuing main stream medication. This made a big impression on me.’ (BMJ Career Focus 2003; 327:166; doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7425.s166)…

After his early support for homeopathy, Professor Ernst has now become, de facto, one of its main opponents. Robin McKie, science editor for The Observer (December 18, 2005) reported Ernst as saying, ‘Homeopathic remedies don’t work. Study after study has shown it is simply the purest form of placebo. You may as well take a glass of water than a homeopathic medicine.’ Ernst, having done the proverbial 180 degree turn, has decided to stand firmly shoulder to shoulder with a number of other leading assailants of non-pharmaceutical therapies, such as Professors Michael Baum and Jonathan Waxman. On 22 May 2006, Baum and twelve other mainly retired surgeons, including Ernst himself, bandied together and co-signed an open letter, published in The Times, which condemned the NHS decision to include increasing numbers of complementary therapies…

As high profile as the Ernsts, Baums and Waxmans of this world might be—their views are not unanimous across the orthodox medical profession. Some of these contrary views were expressed just last Sunday in The Sunday Times (Lost in the cancer maze, 10 December 2006)…

The real loser in open battles between warring factions in healthcare could be the consumer. Imagine how schizophrenic you could become after reading any one of the many newspapers that contains both pro-natural therapy articles and stinging attacks like that found in this week’s Daily Mail. But then again, we may misjudge the consumer who is well known for his or her ability to vote with the feet—regardless. The consumer, just like Robert Sandall, and the millions around the world who continue to indulge in complementary therapies, will ultimately make choices that work for them. ‘Survival of the fittest’ could provide an explanation for why hostile attacks from the orthodox medical community, the media and over-zealous regulators have not dented the steady increase in the popularity of alternative medicine.

Although we live in a technocratic age where we’ve handed so much decision making to the specialists, perhaps this is one area where the might of the individual will reign. Maybe the disillusionment many feel for pharmaceutically-biased healthcare is beginning to kick in. Perhaps the dictates from the white coats will be overruled by the ever-powerful survival instinct and our need to stay in touch with nature, from which we’ve evolved.

END OF QUOTE

Elsewhere, Robert Verkerk even called me the ‘master trickster of evidence-based medicine’ and stated that Prof Ernst and his colleagues appear to be evaluating the ‘wrong’ variable. As Ernst himself admitted, his team are focused on exploring only one of the variables, the ‘specific therapeutic effect’ (Figs 1 and 2). It is apparent, however, that the outcome that is of much greater consequence to healthcare is the combined effect of all variables, referred to by Ernst as the ‘total effect’ (Fig 1). Ernst does not appear to acknowledge that the sum of these effects might differ greatly between experimental and non-experimental situations.

Adding insult to injury, Ernst’s next major apparent faux pas involves his interpretation, or misinterpretation, of results. These fundamental problems exist within a very significant body of Prof Ernst’s work, particularly that which has been most widely publicised because it is so antagonistic towards healing cultures that have in many cases existed and evolved over thousands of years.

By example, a recent ‘systematic review’ of individualised herbal medicine undertaken by Ernst and colleagues started with 1345 peer-reviewed studies. However, all but three (0.2%) of the studies (RCTs) were rejected. These three RCTs in turn each involved very specific types of herbal treatment, targeting patients with IBS, knee osteoarthritis and cancer, the latter also undergoing chemotherapy, respectively. The conclusions of the study, which fuelled negative media worldwide, disconcertingly extended well beyond the remit of the study or its results. An extract follows: “Individualised herbal medicine, as practised in European medical herbalism, Chinese herbal medicine and Ayurvedic herbal medicine, has a very sparse evidence base and there is no convincing evidence that it is effective in any [our emphasis] indication. Because of the high potential for adverse events and negative herb-herb and herb-drug interactions, this lack of evidence for effectiveness means that its use cannot be recommended (Postgrad Med J 2007; 83: 633-637).

Robert Verkerk has recently come to my attention again – as the main author of a lengthy report published in December 2018. Its ‘Executive Summary’ makes the following points relevant in the context of this blog (the numbers in his text were added by me and refer to my comments below):

- This position paper proposes a universal framework, based on ecological and sustainability principles, aimed at allowing qualified health professionals (1), regardless of their respective modalities (disciplines), to work collaboratively and with full participation of the public in efforts to maintain or regenerate health and wellbeing. Accordingly, rather than offering ‘fixes’ for the NHS, the paper offers an approach that may significantly reduce the NHS’s current and growing disease burden that is set to reach crisis point given current levels of demand and funding.

- A major factor driving the relentlessly rising costs of the NHS is its over-reliance on pharmaceuticals (2) to treat a variety of preventable, chronic disorders. These (3) are the result — not of infection or trauma — but rather of our 21st century lifestyles, to which the human body is not well adapted. The failure of pharmaceutically-based approaches to slow down, let alone reverse, the dual burden of obesity and type 2 diabetes means wider roll-out of effective multi-factorial approaches are desperately needed (4).

- The NHS was created at a time when infectious diseases were the biggest killers (5). This is no longer the case, which is why the NHS must become part of a wider system that facilitates health regeneration or maintenance. The paper describes the major mechanisms underlying these chronic metabolic diseases, which are claiming an increasingly large portion of NHS funding. It identifies 12 domains of human health, many of which are routinely thrown out of balance by our contemporary lifestyles. The most effective way of treating lifestyle disorders is with appropriate lifestyle changes that are tailored to individuals, their needs and their circumstances. Such approaches, if appropriately supported and guided, tend to be far more economical and more sustainable as a means of maintaining or restoring people’s health (6).

- A sustainable health system, as proposed in this position paper, is one in which the individual becomes much more responsible for maintaining his or her own health and where more effort is invested earlier in an individual’s life prior to the downstream manifestation of chronic, degenerative and preventable diseases (7). Substantially more education, support and guidance than is typically available in the NHS today will need to be provided by health professionals (1), informed as necessary by a range of markers and diagnostic techniques (8). Healthy dietary and lifestyle choices and behaviours (9) are most effective when imparted early, prior to symptoms of chronic diseases becoming evident and before additional diseases or disorders (comorbidities) have become deeply embedded.

- The timing of the position paper’s release coincides not only with a time when the NHS is in crisis, but also when the UK is deep in negotiations over its extraction from the European Union (EU). The paper includes the identification of EU laws that are incompatible with sustainable health systems, that the UK would do well to reject when the time comes to re-consider the British statute books following the implementation of the Great Repeal Bill (10).

- This paper represents the first comprehensive attempt to apply sustainability principles to the management of human health in the context of our current understanding of human biology and ecology, tailored specifically to the UK’s unique situation. It embodies approaches that work with, rather than against, nature (11). Sustainability principles have already been applied successfully to other sectors such as energy, construction and agriculture.

- It is now imperative that the diverse range of interests and specialisms (12) involved in the management of human health come together. We owe it to future generations to work together urgently, earnestly and cooperatively to develop and thoroughly evaluate new ways of managing and creating health in our society. This blueprint represents a collaborative effort to give this process much needed momentum.

My very short comments:

- I fear that this is meant to include SCAM-practitioners who are neither qualified nor skilled to tackle such tasks.

- Dietary supplements (heavily promoted by the ANH) either have pharmacological effects, in which case they too must be seen as pharmaceuticals, or they are useless, in which case we should not promote them.

- I think ‘some of these’ would be more correct.

- Multifactorial yes, but we must make sure that useless SCAMs are not being pushed in through the back-door. Quackery must not be allowed to become a ‘factor’.

- Only, if we discount cancer and arteriosclerosis, I think.

- SCAM-practitioners have repeatedly demonstrated to be a risk to public health.

- All we know about disease prevention originates from conventional medicine and nothing from SCAM.

- Informed by…??? I would prefer ‘based on evidence’ (evidence being one term that the report does not seem to be fond of).

- All healthy dietary and lifestyle choices and behaviours that are backed by good evidence originate from and are part of conventional medicine, not SCAM.

- Do I detect the nasty whiff a pro-Brexit attitude her? I wonder what the ANH hopes for in a post-Brexit UK.

- The old chestnut of conventional medicine = unnatural and SCAM = natural is being warmed up here, it seems to me. Fallacy galore!

- The ANH would probably like to include a few SCAM-practitioners here.

Call me suspicious, but to me this ANH-initiative seems like a clever smoke-screen behind which they hope to sell their useless dietary supplements and homeopathic remedies to the unsuspecting British public. Am I mistaken?

Highly diluted homeopathic remedies are pure placebos! This is what the best evidence clearly shows. Ergo they cannot be shown in a rigorous study to have effects that differ from placebo. But now there is a study that seems to contradict this widely accepted conclusion.

Can someone please help me to understand what is going on?

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT, 60 patients suffering from insomnia were treated either individualised homeopathy (IH) or placebo for 3 months. Patient-administered sleep diary and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were used the primary and secondary outcomes respectively, measured at baseline, and after 3 months.

Five patients dropped out (verum:2,control:3).Intention to treat sample (n=60) was analysed. Trial arms were comparable at baseline. In the verum group, except sleep diary item 3 (P= 0.371), rest of the outcomes improved significantly (all P < 0.01). In the control group, there were significant improvements in diary item 6 and ISI score (P < 0.01) and just significant improvement in item 5 (P= 0.018). Group differences were significant for items 4, 5 and 6(P < 0.01) and just significant (P= 0.014) for ISI score with moderate to large effect sizes; but non-significant (P > 0.01) for rest of the outcomes.

The authors concluded that in this double-blind, randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled, two parallel arms clinical trial conducted on 60 patients suffering from insomnia, there was statistically significant difference measured in sleep efficiency, total sleep time, time in bed, and ISI score in favour of homeopathy over placebo with moderate to large effect sizes. Group differences were non-significant for rest of the outcomes(i.e. latency to fall asleep, minutes awake in middle of night and minutes awake too early). Individualized homeopathy seemed to produce significantly better effect than placebo. Independent replications and adequately powered trials with enhanced methodological rigor are warranted.

I have studied this article in some detail; its methodology is nicely and fully described in the original paper. To my amazement, I cannot find a flaw that is worth mentioning. Sure, the sample was small, the treatment time short, the outcome measure subjective, the paper comes from a dubious journal, the authors have a clear conflict of interest, even though they deny it – but none of these limitations has the potential to conclusively explain the positive result.

In view of what I stated above and considering what the clinical evidence so far tells us, this is most puzzling.

A 2010 systematic review authored by proponents of homeopathy included 4 RCTs comparing homeopathic medicines to placebo. All involved small patient numbers and were of low methodological quality. None demonstrated a statistically significant difference in outcomes between groups.

My own 2011 not Medline-listed review (Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies Volume 16(3) September 2011 195–199) included several additional studies. Here is its abstract:

The aim of this review was the critical evaluation of evidence for the effectiveness of homeopathy for insomnia and sleep-related disorders. A search of MEDLINE, AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE and Cochrane Central Register was conducted to find RCTs using any form of homeopathy for the treatment of insomnia or sleep-related disorders. Data were extracted according to pre-defined criteria; risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane criteria. Six randomised, placebo-controlled trials met the inclusion criteria. Two studies used individualised homeopathy, and four used standardised homeopathic treatment. All studies had significant flaws; small sample size was the most prevalent limitation. The results of one study suggested that homeopathic remedies were superior to placebo; however, five trials found no significant differences between homeopathy and placebo for any of the main outcomes. Evidence from RCTs does not show homeopathy to be an effective treatment for insomnia and sleep-related disorders.

It follows that the new trial contradicts previously published evidence. In addition, it clearly lacks plausibility, as the remedies used were highly diluted and therefore should be pure placebos. So, what could be the explanation of the new, positive result?

As far as I can see, there are the following possibilities:

- fraud,

- coincidence,

- some undetected/undisclosed bias,

- homeopathy works after all.

I would be most grateful, if someone could help solving this puzzle for me (if needed, I can send you the full text of the new article for assessment).

If so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) ever were to enter the Guinness Book of Records, it would most certainly be because it generates more surveys than any other area of medical inquiry. I have long been rather sceptical about this survey-mania. Therefore, I greet any major new survey with some trepidation.

The aim of this new survey was to obtain up-to-date general population figures for practitioner-led SCAM use in England, and to discover people’s views and experiences regarding access. The researchers commissioned a face-to-face questionnaire survey of a nationally representative adult quota sample (aged ≥15 years). Ten questions were included within Ipsos MORI’s weekly population-based survey. The questions explored 12-month practitioner-led SCAM use, reasons for non-use, views on NHS-provided SCAM, and willingness to pay.

Of 4862 adults surveyed, 766 (16%) had seen a SCAM practitioner. People most commonly visited SCAM practitioners for manual therapies (massage, osteopathy, chiropractic) and acupuncture, as well as yoga, pilates, reflexology, and mindfulness or meditation. Women, people with higher socioeconomic status (SES) and those in south England were more likely to access SCAM. Musculoskeletal conditions (mainly back pain) accounted for 68% of use, and mental health 12%. Most was through self-referral (70%) and self-financing. GPs (17%) or NHS professionals (4%) referred and/or recommended SCAM to users. These SCAM users were more often unemployed, with lower income and social grade, and receiving NHS-funded SCAM. Responders were willing to pay varying amounts for SCAM; 22% would not pay anything. Almost two in five responders felt NHS funding and GP referral and/or endorsement would increase their SCAM use.

The authors concluded that SCAM is commonly used in England, particularly for musculoskeletal and mental health problems, and by affluent groups paying privately. However, less well-off people are also being GP-referred for NHS-funded treatments. For SCAM with evidence of effectiveness (and cost-effectiveness), those of lower SES may be unable to access potentially useful interventions, and access via GPs may be able to address this inequality. Researchers, patients, and commissioners should collaborate to research the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SCAM, and consider its availability on the NHS.

I feel that a few critical thoughts are in order:

- The authors call their survey an ‘up-date’. The survey ran between 25 September and 18 October 2015. That is more than three years ago. I would not exactly call this an up-date!

- Authors (several of whom are known SCAM-enthusiasts) also state that practitioner-led SCAM use was about 5% higher than previous national (UK and England) surveys. This may relate to the authors’ wider SCAM definition, which included 11 more therapies than Hunt et al (a survey from my team), or increased SCAM use since 2005. Despite this uncertainty, the authors write this: Figures from 2005 reported that 12% of the English population used practitioner-led CAM. This 2015 survey has found that 16% of the general population had used practitioner-led CAM in the previous 12 months. Thus, they imply that SCAM-use has been increasing.

- The main justification for running yet another survey presumably was to determine whether SCAM-use has increased, decreased or remained the same (virtually everything else found in the new survey had been shown many times before). To not answer this main question conclusively by asking the same questions as a previous survey is just daft, in my view. We have used the same survey methods at two points one decade apart and found little evidence for an increase, on the contrary: overall, GPs were less likely to endorse CAMs than previously shown (38% versus 19%).

- The main reason why I have long been critical about such surveys is the manner in which their data get interpreted. The present paper is no exception in this respect. Invariably the data show that SCAM is used by those who can afford it. This points to INEQUALITY that needs to be addressed by allowing much more SCAM on the public purse. In other words, such surveys are little more that very expensive and somewhat under-hand promotion of quackery.

- Yes, I know, the present authors are more clever than that; they want the funds limited to SCAM with evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. So, why do they not list those SCAMs together with the evidence for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness? This would enable us to check the validity of the claim that more public money should fund SCAM. I think I know why: such SCAMs do not exist or, at lest, they are extremely rare.

But otherwise the new survey was excellent.