TCM

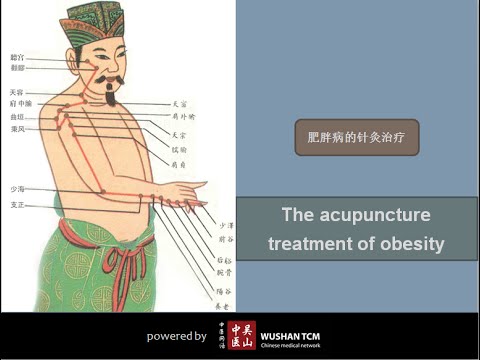

Acupuncture is often promoted as a therapeutic option for obesity and weight control. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of electroacupuncture (EA) on body weight, body mass index (BMI), skin fold thickness, waist circumference and skin temperature of the abdominal region in non-obese women with excessive abdominal subcutaneous fat.

A total of 50 women with excessive abdominal subcutaneous fat (and average BMI of 22) were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- an EA group (n = 25) receiving 10 EA sessions (insertion of needles connected to an electrical stimulator at a frequency of 40 Hz for 40 min),

- a control group (n = 25) that received no treatment.

Outcome measures evaluated included waist circumference, supra-iliac and abdominal skinfolds, body composition and superficial skin temperature (measured by cutaneous thermography) before and after treatment.

Compared with the untreated group, women in the EA group exhibited decreased supra-iliac and abdominal skin folds (p < 0.001), waist circumference (p < 0.001), percentage body fat (p = 0.001) and percentage abdominal fat (p < 0.001). In addition, the EA group showed an elevated skin temperature at the site of the treatment. However, EA did not significantly impact body weight (p = 0.01) or BMI (p = 0.2).

The authors concluded that EA promoted a reduction in abdominal waist circumference, supra-iliac and abdominal skin folds, and percentage body and abdominal fat in women of normal BMI with excessive abdominal subcutaneous fat, as well as an increase in the superficial skin temperature of the abdominal region.

If we did not know that acupuncture researchers were all honest investigators testing hypotheses the best they can, we could almost assume that some are trying to fool us. The set-up of this study is ideally suited to introduce a proper placebo treatment. All one has to do is to not switch on the electrical stimulator in the control group. Why did the researchers not do that? Surely not because they wanted to increase the chances of generating a positive result; that would have been dishonest!!!

So, as it stands, what does the study tell us? I think it shows that, compared to patients who receive no treatment, patients who do receive the ritual of EA are better motivated to adhere to calorie restrictions and dietary advice. Thus, I suggest to re-phrase the conclusions of this trial as follows:

The extra attention of the EA treatment motivated obese patients to eat less which caused a reduction in abdominal waist circumference, supra-iliac and abdominal skin folds, and percentage body and abdominal fat in women of normal BMI with excessive abdominal subcutaneous fat.

This meta-analysis was conducted by researchers affiliated to the Evangelical Clinics Essen-Mitte, Department of Internal and Integrative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. (one of its authors is an early member of my ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME). The paper assessed the safety of acupuncture in oncological patients.

The PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Scopus databases were searched from their inception to August 7, 2020. Randomized controlled trials in oncological patients comparing invasive acupuncture with sham acupuncture, treatment as usual (TAU), or any other active control were eligible. Two reviewers independently extracted data on study characteristics and adverse events (AEs). Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.

Of 4590 screened articles, 65 were included in the analyses. The authors observed that acupuncture was not associated with an increased risk of intervention-related AEs, nonserious AEs, serious AEs, or dropout because of AEs compared with sham acupuncture and active control. Compared with TAU, acupuncture was not associated with an increased risk of intervention-related AEs, serious AEs, or dropout because of AEs but was associated with an increased risk for nonserious AEs (odds ratio, 3.94; 95% confidence interval, 1.16-13.35; P = .03). However, the increased risk of nonserious AEs compared with TAU was not robust against selection bias. The meta-analyses may have been biased because of the insufficient reporting of AEs in the original randomized controlled trials.

The authors concluded that the current review indicates that acupuncture is as safe as sham acupuncture and active controls in oncological patients. The authors recommend researchers heed the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) safety and harm extension for reporting to capture the side effects and better investigate the risk profile of acupuncture in oncology.

You might think this article is not too bad. So, why do I feel that this paper is so bad?

One reason is that the authors included evidence up to August 2020. Since then, there must have been hundreds of further papers on acupuncture. The article was therefore out of date before it was published.

But that is by no means my main reason. We know from numerous investigations that acupuncture studies often fail to report AEs (and thus violate publication ethics). This means that this new analysis is merely an amplification of the under-reporting. It is, in other words, a means of perpetuating a wrong message.

Yes, you might say, but the authors acknowledge this; they even state in the abstract that “The meta-analyses may have been biased because of the insufficient reporting of AEs in the original randomized controlled trials.” True, but this fact does not erase the mistake, it merely concedes it. At the very minimum, the authors should have phrased their conclusion differently, e.g.: the current review confirms that AEs of acupuncture are under-reported in RCTs. Therefore, a meta-analysis of RCTs is unable to verify whether acupuncture is safe. From other types of research, we know that it can cause serious AEs.

An even better solution would have been to abandon or modify the research project when they first came across the mountain of evidence showing that RCTs often fail to mention AEs.

As it stands, the conclusion that acupuncture is as safe as sham acupuncture is simply not true. Since the article probably looks sound to naive readers, I feel that is a particularly good candidate for the WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION.

PS

For those who are interested, here are 4 of my own peer-reviewed articles on the safety of acupuncture (much more can, of course, be found on this blog):

- Patient safety incidents from acupuncture treatments: a review of reports to the National Patient Safety Agency – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Acupuncture–a critical analysis – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Prospective studies of the safety of acupuncture: a systematic review – PubMed (nih.gov)

- The risks of acupuncture – PubMed (nih.gov)

Acupuncture for animals has a long history in China. In the West, it was introduced in the 1970s when acupuncture became popular for humans. A recent article sums up our current knowledge on the subject. Here is an excerpt:

Acupuncture is used mainly for functional problems such as those involving noninfectious inflammation, paralysis, or pain. For small animals, acupuncture has been used for treating arthritis, hip dysplasia, lick granuloma, feline asthma, diarrhea, and certain reproductive problems. For larger animals, acupuncture has been used for treating downer cow syndrome, facial nerve paralysis, allergic dermatitis, respiratory problems, nonsurgical colic, and certain reproductive disorders.Acupuncture has also been used on competitive animals. There are veterinarians who use acupuncture along with herbs to treat muscle injuries in dogs and cats. Veterinarians charge around $85 for each acupuncture session.[8]Veterinary acupuncture has also recently been used on more exotic animals, such as chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)[9] and an alligator with scoliosis,[10] though this is still quite rare.

To put it in a nutshell: acupuncture for animals is not evidence-based.

How can I be so sure?

Because ref 1 in the text above refers to our paper. Here is its abstract:

Acupuncture is a popular complementary treatment option in human medicine. Increasingly, owners also seek acupuncture for their animals. The aim of the systematic review reported here was to summarize and assess the clinical evidence for or against the effectiveness of acupuncture in veterinary medicine. Systematic searches were conducted on Medline, Embase, Amed, Cinahl, Japana Centra Revuo Medicina and Chikusan Bunken Kensaku. Hand-searches included conference proceedings, bibliographies, and contact with experts and veterinary acupuncture associations. There were no restrictions regarding the language of publication. All controlled clinical trials testing acupuncture in any condition of domestic animals were included. Studies using laboratory animals were excluded. Titles and abstracts of identified articles were read, and hard copies were obtained. Inclusion and exclusion of studies, data extraction, and validation were performed independently by two reviewers. Methodologic quality was evaluated by means of the Jadad score. Fourteen randomized controlled trials and 17 nonrandomized controlled trials met our criteria and were, therefore, included. The methodologic quality of these trials was variable but, on average, was low. For cutaneous pain and diarrhea, encouraging evidence exists that warrants further investigation in rigorous trials. Single studies reported some positive intergroup differences for spinal cord injury, Cushing’s syndrome, lung function, hepatitis, and rumen acidosis. These trials require independent replication. On the basis of the findings of this systematic review, there is no compelling evidence to recommend or reject acupuncture for any condition in domestic animals. Some encouraging data do exist that warrant further investigation in independent rigorous trials.

This evidence is in sharp contrast to the misinformation published by the ‘IVAS’ (International Veterinary Acupuncture Society). Under the heading “For Which Conditions is Acupuncture Indicated?“, they propagate the following myth:

Acupuncture is indicated for functional problems such as those that involve paralysis, noninfectious inflammation (such as allergies), and pain. For small animals, the following are some of the general conditions which may be treated with acupuncture:

- Musculoskeletal problems, such as arthritis, intervertebral disk disease, or traumatic nerve injury

- Respiratory problems, such as feline asthma

- Skin problems such as lick granulomas and allergic dermatitis

- Gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea

- Selected reproductive problems

For large animals, acupuncture is again commonly used for functional problems. Some of the general conditions where it might be applied are the following:

- Musculoskeletal problems such as sore backs or downer cow syndrome

- Neurological problems such as facial paralysis

- Skin problems such as allergic dermatitis

- Respiratory problems such as heaves and “bleeders”

- Gastrointestinal problems such as nonsurgical colic

- Selected reproductive problems

In addition, regular acupuncture treatment can treat minor sports injuries as they occur and help to keep muscles and tendons resistant to injury. World-class professional and amateur athletes often use acupuncture as a routine part of their training. If your animals are involved in any athletic endeavor, such as racing, jumping, or showing, acupuncture can help them keep in top physical condition.

And what is the conclusion?

Perhaps this?

Never trust the promotional rubbish produced by SCAM organizations.

The Lancet is a top medical journal, no doubt. But even such journals can make mistakes, even big ones, as the Wakefield story illustrates. But sometimes, the mistakes are seemingly minor and so well hidden that the casual reader is unlikely to find them. Such mistakes can nevertheless be equally pernicious, as they might propagate untruths or misunderstandings that have far-reaching consequences.

A recent Lancet paper might be an example of this phenomenon. It is entitled “Management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer“, unquestionably an important subject. Its abstract reads as follows:

_______________________

Improvements in early detection and treatment have led to a growing prevalence of survivors of cancer worldwide.

Models of care fail to address adequately the breadth of physical, psychosocial, and supportive care needs of those who survive cancer. In this Series paper, we summarise the evidence around the management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of adult cancers and how to cover these issues in a consultation. Reviewing the patient’s history of cancer and treatments highlights potential long-term or late effects to consider, and recommended surveillance for recurrence. Physical consequences of specific treatments to identify include cardiac dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, lymphoedema, peripheral neuropathy, and osteoporosis. Immunotherapies can cause specific immune-related effects most commonly in the gastrointestinal tract, endocrine system, skin, and liver. Pain should be screened for and requires assessment of potential causes and non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches to management. Common psychosocial issues, for which there are effective psychological therapies, include fear of recurrence, fatigue, altered sleep and cognition, and effects on sex and intimacy, finances, and employment. Review of lifestyle factors including smoking, obesity, and alcohol is necessary to reduce the risk of recurrence and second cancers. Exercise can improve quality of life and might improve cancer survival; it can also contribute to the management of fatigue, pain, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and cognitive impairment. Using a supportive care screening tool, such as the Distress Thermometer, can identify specific areas of concern and help prioritise areas to cover in a consultation.

_____________________________

You can see nothing wrong? Me neither! We need to dig deeper into the paper to find what concerns me.

In the actual article, the authors state that “there is good evidence of benefit for … acupuncture …”[1]; the same message was conveyed in one of the tables. In support of these categorical statements, the authors quote the current Cochrane review entitled “Acupuncture for cancer pain in adults”. Its abstract reads as follows:

Background: Forty per cent of individuals with early or intermediate stage cancer and 90% with advanced cancer have moderate to severe pain and up to 70% of patients with cancer pain do not receive adequate pain relief. It has been claimed that acupuncture has a role in management of cancer pain and guidelines exist for treatment of cancer pain with acupuncture. This is an updated version of a Cochrane Review published in Issue 1, 2011, on acupuncture for cancer pain in adults.

Objectives: To evaluate efficacy of acupuncture for relief of cancer-related pain in adults.

Search methods: For this update CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, and SPORTDiscus were searched up to July 2015 including non-English language papers.

Selection criteria: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated any type of invasive acupuncture for pain directly related to cancer in adults aged 18 years or over.

Data collection and analysis: We planned to pool data to provide an overall measure of effect and to calculate the number needed to treat to benefit, but this was not possible due to heterogeneity. Two review authors (CP, OT) independently extracted data adding it to data extraction sheets. Data sheets were compared and discussed with a third review author (MJ) who acted as arbiter. Data analysis was conducted by CP, OT and MJ.

Main results: We included five RCTs (285 participants). Three studies were included in the original review and two more in the update. The authors of the included studies reported benefits of acupuncture in managing pancreatic cancer pain; no difference between real and sham electroacupuncture for pain associated with ovarian cancer; benefits of acupuncture over conventional medication for late stage unspecified cancer; benefits for auricular (ear) acupuncture over placebo for chronic neuropathic pain related to cancer; and no differences between conventional analgesia and acupuncture within the first 10 days of treatment for stomach carcinoma. All studies had a high risk of bias from inadequate sample size and a low risk of bias associated with random sequence generation. Only three studies had low risk of bias associated with incomplete outcome data, while two studies had low risk of bias associated with allocation concealment and one study had low risk of bias associated with inadequate blinding. The heterogeneity of methodologies, cancer populations and techniques used in the included studies precluded pooling of data and therefore meta-analysis was not carried out. A subgroup analysis on acupuncture for cancer-induced bone pain was not conducted because none of the studies made any reference to bone pain. Studies either reported that there were no adverse events as a result of treatment, or did not report adverse events at all.

Authors’ conclusions: There is insufficient evidence to judge whether acupuncture is effective in treating cancer pain in adults.

This conclusion is undoubtedly in stark contrast to the categorical statement of the Lancet authors: “there is good evidence of benefit for … acupuncture …“

What should be done to prevent people from getting misled in this way?

- The Lancet should correct the error. It might be tempting to do this by simply exchanging the term ‘good’ with ‘some’. However, this would still be misleading, as there is some evidence for almost any type of bogus therapy.

- Authors, reviewers, and editors should do their job properly and check the original sources of their quotes.

PS

In case someone argued that the Cochrane review is just one of many, here is the conclusion of an overview of 15 systematic reviews on the subject: The … findings emphasized that acupuncture and related therapies alone did not have clinically significant effects at cancer-related pain reduction as compared with analgesic administration alone.

A press release informs us that the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Government of India recently signed an agreement to establish the ‘WHO Global Centre for Traditional Medicine’. This global knowledge centre for traditional medicine, supported by an investment of USD 250 million from the Government of India, aims to harness the potential of traditional medicine from across the world through modern science and technology to improve the health of people and the planet.

“For many millions of people around the world, traditional medicine is the first port of call to treat many diseases,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “Ensuring all people have access to safe and effective treatment is an essential part of WHO’s mission, and this new center will help to harness the power of science to strengthen the evidence base for traditional medicine. I’m grateful to the Government of India for its support, and we look forward to making it a success.”

The term traditional medicine describes the total sum of the knowledge, skills and practices indigenous and different cultures have used over time to maintain health and prevent, diagnose and treat physical and mental illness. Its reach encompasses ancient practices such as acupuncture, ayurvedic medicine and herbal mixtures as well as modern medicines.

“It is heartening to learn about the signing of the Host Country Agreement for the establishment of Global Centre for Traditional Medicine (GCTM). The agreement between Ministry of Ayush and World Health Organization (WHO) to establish the WHO-GCTM at Jamnagar, Gujarat, is a commendable initiative,” said Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India. “Through various initiatives, our government has been tireless in its endeavour to make preventive and curative healthcare, affordable and accessible to all. May the global centre at Jamnagar help in providing the best healthcare solutions to the world.”

The new WHO centre will concentrate on building a solid evidence base for policies and standards on traditional medicine practices and products and help countries integrate it as appropriate into their health systems and regulate its quality and safety for optimal and sustainable impact.

The new centre focuses on four main strategic areas: evidence and learning; data and analytics; sustainability and equity; and innovation and technology to optimize the contribution of traditional medicine to global health and sustainable development.

The onsite launch of the new WHO global centre for traditional medicine in Jamnagar, Gujarat, India will take place on April 21, 2022.

__________________________

Of course, one must wait and see who will direct the unit and what work the new centre produces. But I cannot help feeling a little anxious. The press release is full of hot air and platitudes and the track record of the Indian Ministry of Ayush is quite frankly abominable. Here are a few of my previous posts that, I think, justify this statement:

- Mucormycosis (black fungus): is the Indian AYUSH ministry trying to decimate the population?

- The ‘AYUSH COVID-19 Helpline’: have they gone bonkers?

- Individualized Homeopathic Medicines for Cutaneous Warts – the dishonesty of homeopaths continues

- Ever wondered what a homeopathic egg on the face looks like?

- An RCT on the efficacy of ayurvedic treatment on asymptomatic COVID-19 patients

- Has homeopathy caused the dramatic decline of COVID-19 cases in India?

- Eight new products aimed at mitigating COVID-19. But do they really work?

- Siddha doctors have joined those claiming to have found a cure for COVID-19

- COVID-19: homeopathy gone berserk in Mumbai

- Brazil and India collaborate in the promotion of quackery

- Hard to believe: dangerous GOVERNMENTAL advice regarding SCAM for the corona virus pandemic

WATCH THIS SPACE!

Ginseng plants belong to the genus Panax and include:

- Panax ginseng (Korean ginseng),

- Panax notoginseng (South China ginseng),

- and Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng).

They are said to have a range of therapeutic activities, some of which could render ginseng a potential therapy for viral or post-viral infections. Ginseng has therefore been used to treat fatigue in various patient groups and conditions. But does it work for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also often called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)? This condition is a complex, little-understood, and often disabling chronic illness for which no curative or definitive therapy has yet been identified.

This systematic review aimed to assess the current state of evidence regarding ginseng for CFS. Multiple databases were searched from inception to October 2020. All data was extracted independently and in duplicates. Outcomes of interest included the effectiveness and safety of ginseng in patients with CFS.

A total of two studies enrolling 68 patients were deemed eligible: one randomized clinical trial and one prospective observational study. The certainty of evidence in the effectiveness outcome was low and moderate in both studies, while the safety evidence was very low as reported from one study.

The authors concluded that the study findings highlight a potential benefit of ginseng therapy in the treatment of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions due to limited clinical studies. The paucity of data warrants limited confidence. There is a need for future rigorous studies to provide further evidence.

To get a feeling of how good or bad the evidence truly is, we must of course look at the primary studies.

The prospective observational study turns out to be a mere survey of patients using all sorts of treatments. It included 155 subjects who provided information on fatigue and treatments at baseline and follow-up. Of these subjects, 87% were female and 79% were middle-aged. The median duration of fatigue was 6.7 years. The percentage of users who found a treatment helpful was greatest for coenzyme Q10 (69% of 13 subjects), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (65% of 17 subjects), and ginseng (56% of 18 subjects). Treatments at 6 months that predicted subsequent fatigue improvement were vitamins (p = .08), vigorous exercise (p = .09), and yoga (p = .002). Magnesium (p = .002) and support groups (p = .06) were strongly associated with fatigue worsening from 6 months to 2 years. Yoga appeared to be most effective for subjects who did not have unclear thinking associated with fatigue.

The second study investigated the effect of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) on chronic fatigue (CF) by various measurements and objective indicators. Participants were randomized to KRG or placebo group (1:1 ratio) and visited the hospital every 2 weeks while taking 3 g KRG or placebo for 6 weeks and followed up 4 weeks after the treatment. The fatigue visual analog score (VAS) declined significantly in each group, but there were no significant differences between the groups. The 2 groups also had no significant differences in the secondary outcome measurements and there were no adverse events. Sub-group analysis indicated that patients with initial fatigue VAS below 80 mm and older than 50 years had significantly greater reductions in the fatigue VAS if they used KRG rather than placebo. The authors concluded that KRG did not show absolute anti-fatigue effect but provided the objective evidence of fatigue-related measurement and the therapeutic potential for middle-aged individuals with moderate fatigue.

I am at a loss in comprehending how the authors of the above-named review could speak of evidence for potential benefit. The evidence from the ‘observational study’ is largely irrelevant for deciding on the effectiveness of ginseng, and the second, more rigorous study fails to show that ginseng has an effect.

So, is ginseng a promising treatment for ME?

I doubt it.

On 27 January 2022, I conducted a very simple Medline search using the search term ‘Chinese Herbal Medicine, Review, 2022’. Its results were remarkable; here are the 30 reviews I found:

- Zhu, S. J., Wang, R. T., Yu, Z. Y., Zheng, R. X., Liang, C. H., Zheng, Y. Y., Fang, M., Han, M., & Liu, J. P. (2022). Chinese herbal medicine for myasthenia gravis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Integrative medicine research, 11(2), 100806.

- Lu, J., Li, W., Gao, T., Wang, S., Fu, C., & Wang, S. (2022). The association study of chemical compositions and their pharmacological effects of Cyperi Rhizoma (Xiangfu), a potential traditional Chinese medicine for treating depression. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 287, 114962.

- Su, F., Sun, Y., Zhu, W., Bai, C., Zhang, W., Luo, Y., Yang, B., Kuang, H., & Wang, Q. (2022). A comprehensive review of research progress on the genus Arisaema: Botany, uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 285, 114798.

- Nanjala, C., Ren, J., Mutie, F. M., Waswa, E. N., Mutinda, E. S., Odago, W. O., Mutungi, M. M., & Hu, G. W. (2022). Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and conservation of the genus Calanthe R. Br. (Orchidaceae). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 285, 114822.

- Li, M., Jiang, H., Hao, Y., Du, K., Du, H., Ma, C., Tu, H., & He, Y. (2022). A systematic review on botany, processing, application, phytochemistry and pharmacological action of Radix Rehmnniae. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 285, 114820.

- Mutinda, E. S., Mkala, E. M., Nanjala, C., Waswa, E. N., Odago, W. O., Kimutai, F., Tian, J., Gichua, M. K., Gituru, R. W., & Hu, G. W. (2022). Traditional medicinal uses, pharmacology, phytochemistry, and distribution of the Genus Fagaropsis (Rutaceae). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 284, 114781.

- Xu, Y., Liu, J., Zeng, Y., Jin, S., Liu, W., Li, Z., Qin, X., & Bai, Y. (2022). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and quality control of medicinal genus Aralia: A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 284, 114671.

- Peng, Y., Chen, Z., Li, Y., Lu, Q., Li, H., Han, Y., Sun, D., & Li, X. (2022). Combined therapy of Xiaoer Feire Kechuan oral liquid and azithromycin for mycoplasma Pneumoniae pneumonia in children: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 96, 153899.

- Xu, W., Li, B., Xu, M., Yang, T., & Hao, X. (2022). Traditional Chinese medicine for precancerous lesions of gastric cancer: A review. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 146, 112542.

- Wang, Y., Greenhalgh, T., Wardle, J., & Oxford TCM Rapid Review Team (2022). Chinese herbal medicine (“3 medicines and 3 formulations”) for COVID-19: rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 28(1), 13–32.

- Chen, X., Lei, Z., Cao, J., Zhang, W., Wu, R., Cao, F., Guo, Q., & Wang, J. (2022). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and current uses of underutilized Xanthoceras sorbifolium bunge: A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 283, 114747.

- Liu, X., Li, Y., Bai, N., Yu, C., Xiao, Y., Li, C., & Liu, Z. (2022). Updated evidence of Dengzhan Shengmai capsule against ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 283, 114675.

- Chen, J., Zhu, Z., Gao, T., Chen, Y., Yang, Q., Fu, C., Zhu, Y., Wang, F., & Liao, W. (2022). Isatidis Radix and Isatidis Folium: A systematic review on ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 283, 114648.

- Tian, J., Shasha, Q., Han, J., Meng, J., & Liang, A. (2022). A review of the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Fructus Gardeniae (Zhi-zi). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 114984. Advance online publication.

- Wong, A. R., Yang, A., Li, M., Hung, A., Gill, H., & Lenon, G. B. (2022). The Effects and Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine on Blood Lipid Profiles in Placebo-Controlled Weight-Loss Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2022, 1368576.

- Lu, C., Ke, L., Li, J., Wu, S., Feng, L., Wang, Y., Mentis, A., Xu, P., Zhao, X., & Yang, K. (2022). Chinese Medicine as an Adjunctive Treatment for Gastric Cancer: Methodological Investigation of meta-Analyses and Evidence Map. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 797753.

- Niu, L., Xiao, L., Zhang, X., Liu, X., Liu, X., Huang, X., & Zhang, M. (2022). Comparative Efficacy of Chinese Herbal Injections for Treating Severe Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 743486.

- Zhang, L., Huang, J., Zhang, D., Lei, X., Ma, Y., Cao, Y., & Chang, J. (2022). Targeting Reactive Oxygen Species in Atherosclerosis via Chinese Herbal Medicines. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2022, 1852330.

- Zhou, X., Guo, Y., Yang, K., Liu, P., & Wang, J. (2022). The signaling pathways of traditional Chinese medicine in promoting diabetic wound healing. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 282, 114662.

- Yang, M., Shen, C., Zhu, S. J., Zhang, Y., Jiang, H. L., Bao, Y. D., Yang, G. Y., & Liu, J. P. (2022). Chinese patent medicine Aidi injection for cancer care: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 282, 114656.

- Liu, H., & Wang, C. (2022). The genus Asarum: A review on phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology and pharmacokinetics. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 282, 114642.

- Lin, Z., Zheng, J., Chen, M., Chen, J., & Lin, J. (2022). The Efficacy and Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 56 Randomized Controlled Trials. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2022, 6887988.

- Yu, R., Zhang, S., Zhao, D., & Yuan, Z. (2022). A systematic review of outcomes in COVID-19 patients treated with western medicine in combination with traditional Chinese medicine versus western medicine alone. Expert reviews in molecular medicine, 24, e5.

- Mo, X., Guo, D., Jiang, Y., Chen, P., & Huang, L. (2022). Isolation, structures and bioactivities of the polysaccharides from Radix Hedysari: A review. International journal of biological macromolecules, 199, 212–222.

- Yang, L., Chen, X., Li, C., Xu, P., Mao, W., Liang, X., Zuo, Q., Ma, W., Guo, X., & Bao, K. (2022). Real-World Effects of Chinese Herbal Medicine for Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy (REACH-MN): Protocol of a Registry-Based Cohort Study. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 760482.

- Zhang, R., Zhang, Q., Zhu, S., Liu, B., Liu, F., & Xu, Y. (2022). Mulberry leaf (Morus alba L.): A review of its potential influences in mechanisms of action on metabolic diseases. Pharmacological research, 175, 106029.

- Yuan, J. Y., Tong, Z. Y., Dong, Y. C., Zhao, J. Y., & Shang, Y. (2022). Research progress on icariin, a traditional Chinese medicine extract, in the treatment of asthma. Allergologia et immunopathologia, 50(1), 9–16.

- Zeng, B., Wei, A., Zhou, Q., Yuan, M., Lei, K., Liu, Y., Song, J., Guo, L., & Ye, Q. (2022). Andrographolide: A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and clinical trials and pharmaceutical researches. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 36(1), 336–364.

- Zhang, L., Xie, Q., & Li, X. (2022). Esculetin: A review of its pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 36(1), 279–298.

- Wang, D. C., Yu, M., Xie, W. X., Huang, L. Y., Wei, J., & Lei, Y. H. (2022). Meta-analysis on the effect of combining Lianhua Qingwen with Western medicine to treat coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of integrative medicine, 20(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2021.10.005

The amount of reviews alone is remarkable, I think: more than one review per day! Apart from their multitude, the reviews are noteworthy for other reasons as well.

- Their vast majority arrived at positive or at least encouraging conclusions.

- Most of the primary studies are from China (and we have often discussed how unreliable these trials are).

- Many of the primary studies are not accessible.

- Those that are accessible tend to be of lamentable quality.

I fear that all this is truly dangerous. The medical literature is being swamped with reviews of Chinese herbal medicine and other TCM modalities. Collectively they give the impression that these treatments are supported by sound evidence. Yet, the exact opposite is the case.

The process that is happening in front of our very eyes is akin to that of money laundering. Unreliable and often fraudulent data is being white-washed and presented to us as evidence.

The result:

WE ARE BEING SYSTEMATICALLY MISLED!

Auriculotherapy (or ear acupuncture) is the use of electrical, mechanical, or other stimuli at specific points on the outer ear for therapeutic purposes. It was invented by the French neurologist Paul Nogier (1908–1996) who published his “Treatise of Auriculotherapy” in 1961. Auriculotherapy is based on the idea that the human outer ear is an area that reflects the entire body. Proponents of auriculotherapy refer to maps where our inner organs and body parts are depicted on the outer ear. These maps are not in line with our knowledge of anatomy and physiology. Auriculotherapy thus lacks plausibility.

This single-blind randomized, placebo-controlled study aimed to investigate the effect of auriculotherapy on the intensity of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) symptoms.

Ninety-one women were randomly assigned to

- Auriculotherapy (AG),

- Placebo (PG),

- Control (CG) groups.

The intervention was 8 weeks long, done once per week. At each session in AG the microneedles were placed in seven points related to PMS symptoms (Anxiety; Endocrine; Muscle relaxation; Analgesia; Kidney; Shen Men; and Sympathetic). At PG the microneedles also were placed in seven points but unrelated to PMS symptoms (Tonsils; Vocal cords; Teeth; Eyes; Allergy; Mouth; and External nose). The women allocate in the CG received o intervention during the evaluation period.

Assessments of PMS symptoms (Premenstrual Syndrome Screening Tool), musculoskeletal pain (Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory), and quality of life (WHOQOL-Bref) were done at baseline, before the 5th session, after program completion, and a month follow-up.

The AG and PG showed significantly lower scores of PMS symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, and anxiety. On the quality of life and follow-up analysis, the significance was observed only in PG.

The authors concluded that auriculotherapy can be used as adjunctive therapy to reduce the physical and mood PMS symptoms.

If I understand it correctly (the paper is unclear), verum and placebo were both better than no intervention but showed no significant differences when compared to each other. This is strong evidence that auriculotherapy is, in fact, a placebo. To make matters worse, in the follow-up analysis placebo seems to be superior to auriculotherapy.

Another issue might be adverse effects. Microneedle implants can cause severe complications. Thus it is mandatory to monitor adverse effects in clinical trials. This does not seem to have happened in this case.

The mind boggles!

How on earth could the authors conclude that auriculotherapy can be used as adjunctive therapy to reduce the physical and mood PMS symptoms.

The answer: a case of scientific misconduct?

This systematic review examined the efficacy of acupressure on depression. Literature searches were performed on PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, MEDLINE, and China National Knowledge (CNKI). Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or single-group trials in which acupressure was compared with various control methods or baseline (i.e. no treatment) in people with depression were included. Data were synthesized using a random-effects or a fixed-effects model to analyze the impacts of acupressure treatment on depression and anxiety in people with depression. The primary outcome measures were depression symptoms quantified by various means. Subgroups were created, and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore which factors are relevant to the greater or lesser effects of treating symptoms.

A total of 14 RCTs (1439 participants) were identified. Analysis of the between-group showed that acupressure was effective in reducing depression [Standardized mean differences (SMDs) = -0.58, 95%CI: -0.85 to -0.32, P < 0.0001] and anxiety (SMD = -0.67, 95%CI: -0.99 to -0.36, P < 0.0001) in participants with mild-to-moderate primary and secondary depression. Subgroup analyses suggested that acupressure significantly reduced depressive symptoms compared with different controlled conditions and in participants with different ages, clinical conditions, and duration of intervention. Adverse events, including hypotension, dizziness, palpitation, and headache, were reported in only one study.

The authors concluded that the evidence of acupressure for mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms was significant. Importantly, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to study limitations. Future research with a well-designed mixed method is required to consolidate the conclusion and provide an in-depth understanding of potential mechanisms underlying the effects.

I think that more than caution is warranted when interpreting these data. In fact, it would have been surprising if the meta-analyses had NOT generated an overall positive result. This is because in several studies there was no attempt to control for the extra attention or the placebo effect of administering acupressure. In most of the trials where this had been taken care of (i.e. patient-blinded, sham-controlled studies), there were no checks for the success of blinding. Thus it is possible, even likely that many patients correctly guessed what treatment they received. In turn, this means that the outcomes of these trials were also largely due to placebo effects.

Overall, this paper is therefore a prime example of a biased review of biased primary studies. The phenomenon can be aptly described by the slogan:

RUBBISH IN, RUBBISH OUT!

My second entry into this competition is so special that I will show you its complete, unadulterated abstract. Here it is:

Objective

To compare the safety differences between Chinese medicine (CM) and Western medicine (WM) based on Chinese Spontaneous Reporting Database (CSRD).

Methods

Reports of adverse events (AEs) caused by CM and WM in the CSRD between 2010 and 2011 were selected. The following assessment indicators were constructed: the proportion of serious AEs (PSE), the average number of AEs (ANA), and the coverage rate of AEs (CRA). Further comparisons were also conducted, including the drugs with the most reported serious AEs, the AEs with the biggest report number, and the 5 serious AEs of interest (including death, anaphylactic shock, coma, dyspnea and abnormal liver function).

Results

The PSE, ANA and CRA of WM were 1.09, 8.23 and 2.35 times higher than those of CM, respectively. The top 10 drugs with the most serious AEs were mainly injections for CM and antibiotics for WM. The AEs with the most reports were rash, pruritus, nausea, dizziness and vomiting for both CM and WM. The proportions of CM and WM in anaphylactic shock and coma were similar. For abnormal liver function and death, the proportions of WM were 5.47 and 3.00 times higher than those of CM, respectively.

Conclusion

Based on CSRD, CM was safer than WM at the average level from the perspective of adverse drug reactions.

__________________

Perhaps there will be readers who do not quite understand why I find this paper laughable. Let me try to answer their question by suggesting a few other research subjects of similar farcicality.

- A comparison of the safety of vitamins and chemotherapy.

- A study of the relative safety of homeopathic remedies and antibiotics.

- An investigation into the risks of sky diving in comparison with pullover knitting.

- A study of the pain caused by an acupuncture needle compared to molar extraction.

In case my point is still not clear: comparing the safety of one intervention to one that is fundamentally different in terms of its nature and efficacy does simply make no sense. If one wanted to conduct such an investigation, it would only be meaningful, if one would consider the risk-benefit balance of both treatments.

The fact that this is not done here discloses the above paper as an embarrassing attempt at promoting Traditional Chinese Medicine.

PS

In case you wonder about the affiliations of the authors and their support:

- School of Management, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing, 210003, China

Jian-xiang Wei - School of Internet of Things, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing, 210003, China

Zhi-qiang Lu, Guan-zhong Feng & Yun-xia Zhu

The review was supported by the Major Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Jiangsu Universities and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province, China.