TCM

Manual therapy is considered a safe and less painful method and has been increasingly used to alleviate chronic neck pain. However, there is controversy about the effectiveness of manipulation therapy on chronic neck pain. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed to determine the effectiveness of manipulative therapy for chronic neck pain.

A search of the literature was conducted on seven databases (PubMed, Cochrane Center Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, Medline, CNKI, WanFang, and SinoMed) from the establishment of the databases to May 2022. The review included RCTs on chronic neck pain managed with manipulative therapy compared with sham, exercise, and other physical therapies. The retrieved records were independently reviewed by two researchers. Further, the methodological quality was evaluated using the PEDro scale. All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan V.5.3 software. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) assessment was used to evaluate the quality of the study results.

Seventeen RCTs, including 1190 participants, were included in this meta-analysis. Manipulative therapy showed better results regarding pain intensity and neck disability than the control group. Manipulative therapy was shown to relieve pain intensity (SMD = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] = [-1.04 to -0.62]; p < 0.0001) and neck disability (MD = -3.65; 95% CI = [-5.67 to – 1.62]; p = 0.004). However, the studies had high heterogeneity, which could be explained by the type and control interventions. In addition, there were no significant differences in adverse events between the intervention and the control groups.

The authors concluded that manipulative therapy reduces the degree of chronic neck pain and neck disabilities.

Only a few days ago, we discussed another systematic review that drew quite a different conclusion: there was very low certainty evidence supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain.

How can this be?

Systematic reviews are supposed to generate reliable evidence!

How can we explain the contradiction?

There are several differences between the two papers:

- One was published in a SCAM journal and the other one in a mainstream medical journal.

- One was authored by Chinese researchers, the other one by an international team.

- One included 17, the other one 23 RCTs.

- One assessed ‘manual/manipulative therapies’, the other one spinal manipulation/mobilization.

The most profound difference is that the review by the Chinese authors is mostly on Chimese massage [tuina], while the other paper is on chiropractic or osteopathic spinal manipulation/mobilization. A look at the Chinese authors’ affiliation is revealing:

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China.

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

What lesson can we learn from this confusion?

Perhaps that Tuina is effective for neck pain?

No!

What the abstract does not tell us is that the Tuina studies are of such poor quality that the conclusions drawn by the Chinese authors are not justified.

What we do learn – yet again – is that

- Chinese papers need to be taken with a large pintch of salt. In the present case, the searches underpinning the review and the evaluations of the included primary studies were clearly poorly conducted.

- Rubbish journals publish rubbish papers. How could the reviewers and the editors have missed the many flaws of this paper? The answer seems to be that they did not care. SCAM journals tend to publish any nonsense as long as the conclusion is positive.

The increasing demand for fertility treatments has led to the rise of private clinics offering so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) treatments. Even King Charles has recently joined in with this situalion. One of the most frequently offered SCAM infertility treatment is acupuncture. However, there is no good evidence to support the effectiveness of acupuncture in treating infertility.

This study evaluated the scope of information provided by SCAM fertility clinics in the UK. A content analysis was conducted on 200 websites of SCAM fertility clinics in the UK that offer acupuncture as a treatment for infertility. Of the 48 clinics that met the eligibility criteria, the majority of the websites did not provide sufficient information on:

- the efficacy,

- the risks,

- the success rates

of acupuncture for infertility.

The authors concluded that this situation has the potential to infringe on patient autonomy, provide false hope and reduce the chances of pregnancy ever being achieved as fertility declines during the time course of ineffective acupuncture treatment.

The authors are keen to point out that their investigation has certain limitations. The study only analysed the information provided on the clinics’ websites and did not assess the quality of the treatment provided by the clinics.

Therefore, the study’s fndings cannot be generalized to the quality of the acupuncture treatment provided by the clinics.

Nonetheless the paper touches on very important issues: far too many health clinics that offer SCAM for this or that indication operate way outside the ethically (and legally) acceptable norm. They advertise their services without making it clear that they are neither effective nor safe. Desperate consumers thus fall for their promises. In the case of infertility, this might result merely in frustration and loss of (often substantial amounts of) money. In the case of serious disease, such as cancer, this often results in premature death.

It is time, I think, that this entire sector is regualted in a way that it does not endanger the well-being, health, or life of consumers.

Charles has a well-documented weakness for so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) – not just any SCAM but predominantly the type of SCAM that is both implausible and ineffective. Therefore, nobody can be all that surprised to read in THE TIMES that he has decided to use SCAM for helping women who have difficulties getting pregnant.

If one really wanted to employ SCAM for this aim one is spoilt for choice. In fact, there are only few SCAMs that don’t claim to be useful for this purpose.

A recent review, for instance, suggested that some supplements might be helpful. Other authors advocate SCAMs such as acupuncture, moxibustion, Chinese herbal medicine, psychological intervention, biosimilar electrical stimulation, homeopathy, or hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Yes, I know! The evidence for these treatments is lousy, and I would never issue a recommendation based on such flimsy evidence.

Yet, the SCAM project at Dumfries House, the Scottish stately home Charles restored in 2007, offers acupuncture, reflexology, massage, yoga, and hypnotherapy for infertile women.

REFLEXOLOGY for female infertility?

Reflexology, also called zone therapy, is a manual treatment where pressure is applied usually to the sole of the patient’s foot and sometimes also to other areas such as the hands or ears. According to its proponents, foot reflexology is more than a simple foot massage that makes no therapeutic claims beyond relaxation. It is based on the idea that the human body is divided into 10 zones each of which is represented on the sole of the foot. Reflexologists employ maps of the sole of the foot where the body’s organs are depicted. By massaging specific zones which are assumed to be connected to specific organs, reflexologists believe to positively influence the function of these organs. While reflexology is mostly used as a therapy, some therapists also claim they can diagnose health problems through feeling tender or gritty areas on the sole of the foot which, they claim, correspond to specific organs.

Reflexology is not merely implausible as a treatment for infertility, it also boasts of some fairly rigorous trial evidence. A clinical trial (perhaps even the most rigorous of all the trials of SCAM for female fertility problems) testing whether foot reflexology might have a positive effect on the induction of ovulation stated that “the results suggest that any effect on ovulation would not be clinically relevant”.

So, as so often before in the realm of SCAM, Charles has demonstrated that his lack of critical thinking leads him to the least promising options.

Well done, Your Majesty!

This study investigated the potential benefits of auricular point acupressure on cerebrovascular function and stroke prevention among adults with a high risk of stroke.

A randomized controlled study was performed with 105 adults at high risk for stroke between March and July 2021. Participants were randomly allocated to receive either

- auricular point acupressure with basic lifestyle interventions (n = 53) or

- basic lifestyle interventions alone (n = 52) for 2 weeks.

The primary outcome was the kinematic and dynamic indices of cerebrovascular function, as well as the CVHP score at week 2, measured by the Doppler ultrasonography and pressure transducer on carotids.

Of the 105 patients, 86 finished the study. At week 2, the auricular point acupressure therapy with lifestyle intervention group had higher kinematic indices, cerebrovascular hemodynamic parameters score, and lower dynamic indices than the lifestyle intervention group.

The authors concluded that ccerebrovascular function and cerebrovascular hemodynamic parameters score were greater improved among the participants undergoing auricular point acupressure combined with lifestyle interventions than lifestyle interventions alone. Hence, the auricular point acupressure can assist the stroke prevention.

Acupuncture is a doubtful therapy.

Acupressure is even more questionable.

Ear acupressure is outright implausible.

The authors discuss that the physiological mechanism underlying the effect of APA therapy on cerebrovascular hemodynamic function is not fully understood at present. There may be two possible explanations.

- First, a previous study has demonstrated that auricular acupuncture can directly increase mean blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery.

- Second, cerebrovascular hemodynamic function is indirectly influenced by the effect of APA therapy on blood pressure.

I think there is a much simpler explanation: the observed effects are directly or indirectly due to placebo. As regular listeners of this blog know only too well by now, the A+B versus B study design cannot account for placebo effects. Sadly, the authors of this study hardly discuss this explanation – that’s why they had to publish their findings in just about the worst SCAM journal of them all: EBCAM.

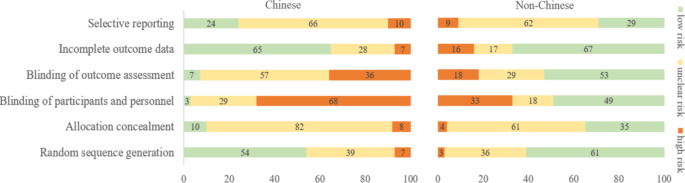

There are debates in acupuncture-related systematic reviews and meta-analyses on whether searching Chinese databases to get more Chinese-language studies may increase the risk of bias and overestimate the effect size, and whether the treatment effects of acupuncture differ between Chinese and non-Chinese populations.

For this meta-epidemiological study, a team of investigators searched the Cochrane Library from its inception until December 2021, and identified systematic reviews and meta-analyses with acupuncture as one of the interventions. Paired reviewers independently screened the reviews and extracted the information. They repeated the meta-analysis of the selected outcomes to separately pool the results of Chinese- and non-Chinese-language acupuncture studies and presented the pooled estimates as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). They calculated the Ratio of ORs (ROR) by dividing the OR of the Chinese-language trials by the OR of the non-Chinese-language trials, and the ROR by dividing the OR of trials addressing Chinese population by the OR of trials addressing non-Chinese population. The researchers thus explored whether the impact of a high risk of bias on the effect size differed between studies published in Chinese- and in non-Chinese-language, and whether the treatment effects of acupuncture differed between Chinese and non-Chinese populations.

The researchers identified 84 Cochrane acupuncture reviews involving 33 Cochrane groups, of which 31 reviews (37%) searched Chinese databases. Searching versus not searching Chinese databases significantly increased the contribution of Chinese-language literature both to the total number of included trials (54% vs. 15%) and the sample size (40% vs. 15%). When compared with non-Chinese-language trials, Chinese-language trials were associated with a larger effect size (pooled ROR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.91). The researchers also observed a higher risk of bias in Chinese-language trials in blinding of participants and personnel (97% vs. 51%) and blinding of outcome assessment (93% vs. 47%). The higher risk of bias was associated with a larger effect estimate in both Chinese language (allocation concealment: high/unclear risk vs. low risk, ROR 0.43, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.87) and non-Chinese-language studies (blinding of participants and personnel: high/unclear risk vs. low risk, ROR 0.41, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.74). However, the team found no evidence that the higher risk of bias would increase the effect size of acupuncture in Chinese-language studies more often than in non-Chinese-language studies (the confidence intervals of all ROR in the high-risk group included 1, Table 3). The researchers further found acupuncture appeared to be more effective in Chinese than in non-Chinese populations.

The authors concluded that the findings of this study suggest the higher risk of bias may lead to an overestimation of the treatment effects of acupuncture but would not increase the treatment effects in Chinese-language studies more often than in other language studies. The difference in treatment effects of acupuncture was probably associated with differences in population characteristics.

The authors discuss that, although searching Chinese databases can substantially increase the number of eligible studies and sample size in acupuncture reviews, the potentially higher risk of bias is an argument that needs to be considered in the inclusion of Chinese-language studies. Patients, investigators, and guideline panels should be cautious when adopting evidence from acupuncture reviews where studies with a high risk of bias contributed with a high weight to the meta-analysis.

The authors observed larger treatment effects of acupuncture in Chinese-language studies than in studies published in other languages. Although the treatment effects of acupuncture tended to be greater in studies with a high risk of bias, this potential overestimation did not differ between studies published in Chinese and in other languages. In other words, the larger treatment effects in Chinese-language studies cannot be explained by a high risk of bias. Furthermore, our study found acupuncture to be more effective in Chinese populations than in other populations, which could at least partly explain the larger treatment effects observed in Chinese-language studies.

I feel that this analysis obfuscates more than it clarifies. As we have discussed often here, acupuncture studies by Chinese researchers (regardless of what language they are published in) hardly ever report negative results, and their findings are often fabricated. It, therefore, is not surprising that their effect sizes are larger than those of other trials.

The only sensible conclusion from this messy and regrettable situation, in my view, is to be very cautious and exclude them from systematic reviews.

I found this acupuncture study from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Sciences, “Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy. As this seems to be a respectable institution, I had a look. What I found was remarkable! Let me show you the abstract in its full beauty:

Background: Pain related to Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) is severe, negatively affecting patients’ quality of life, and often resistant to conventional treatments. Abdominal Acupuncture (AA) is known to be particularly effective for pain, especially chronic and musculoskeletal pain, but it is still poorly studied and never investigated in TMD patients. Objectives: To analyze the efficacy of AA for the treatment of patients with subacute and chronic pain related to TMD and non-responding to previous conventional therapies (occlusal splint, medications, physical therapy).

Methods: Twenty-eight patients, 24 F and four M (mean age 49.36 years), were recruited from January 2019-February 2021. All patients underwent AA treatment: two sessions per week for four weeks, for a total of eight sessions. At the beginning of therapy (T0) and at the end of the cycle (T1) the following data were evaluated: maximum mouth opening (MMO); cranio-facial pain related to TMD (verbal numeric scale, VNS); pain interference with normal activities and quality of life of patients (Brief Pain Inventory, BPI); oral functioning (Oral Behavior Checklist, OBC); impression of treatment effectiveness (Patients’ Global Impression of Improvement, PGI-I Scale). Statistical comparison of data before and after the AA treatment was performed by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test (significance level p < 0.05).

Results: The MMO values were significantly improved after one cycle of AA (p = 0.0002). In addition, TMD-related pain had a statistically significant decline following AA treatment (all p < 0.001). Patients’ general activity and quality of life (BPI) were described as improved following a course of AA, with statistically significant values for all aspects considered (all p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Abdominal acupuncture resulted in effective treatment of subacute/chronic resistant pain related to TMD, capable of improving mandibular function and facial pain, and reduced the interference of pain affecting patients’ quality of life.

_____________________

Shocked?

Me too!

This study did not include a control group. Such uncontrolled studies are not necessarily useless. In areas where there is no prior evidence, they can be a reasonable starting point for further research. In the case of TMD/acupuncture, however, this does not imply. Here we already have about a dozen controlled trials. This means an uncontrolled study cannot possibly contribute to our knowledge. This means that the present study is useless. And that, in turn, means it is unethical.

But even if we ignore all this, the study is very misleading. It concludes that acupuncture improved TMD. This, however, can be doubted!

- What about placebo?

- What about regression toward the mean?

- What about the natural history of the condition?

Bad science is regrettable and dangerous, as it

- wastes resources,

- misleads vulnerable patients,

- violates ethics,

- and undermines trust in science.

I fear that the Italian group has just provided us with a prime example of these points.

Sure, the LP is dangerous nonsense, but this begs the question of whether so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) has anything to offer for patients suffering from ME/CFS. If the LP story tells us anything, then it must be this: we should not trust single trials, particularly if they seem dodgy. In other words, we should look at systematic reviews that synthesize ALL clinical trials and evaluate them critically.

To locate this type of evidence I conducted several Medline searches and found several recent systematic reviews that address the issue:

Context: A variety of interventions have been used in the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Currently, debate exists among health care professionals and patients about appropriate strategies for management.

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of all interventions that have been evaluated for use in the treatment or management of CFS in adults or children.

Data sources: Nineteen specialist databases were searched from inception to either January or July 2000 for published or unpublished studies in any language. The search was updated through October 2000 using PubMed. Other sources included scanning citations, Internet searching, contacting experts, and online requests for articles.

Study selection: Controlled trials (randomized or nonrandomized) that evaluated interventions in patients diagnosed as having CFS according to any criteria were included. Study inclusion was assessed independently by 2 reviewers. Of 350 studies initially identified, 44 met inclusion criteria, including 36 randomized controlled trials and 8 controlled trials.

Data extraction: Data extraction was conducted by 1 reviewer and checked by a second. Validity assessment was carried out by 2 reviewers with disagreements resolved by consensus. A qualitative synthesis was carried out and studies were grouped according to type of intervention and outcomes assessed.

Data synthesis: The number of participants included in each trial ranged from 12 to 326, with a total of 2801 participants included in the 44 trials combined. Across the studies, 38 different outcomes were evaluated using about 130 different scales or types of measurement. Studies were grouped into 6 different categories. In the behavioral category, graded exercise therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy showed positive results and also scored highly on the validity assessment. In the immunological category, both immunoglobulin and hydrocortisone showed some limited effects but, overall, the evidence was inconclusive. There was insufficient evidence about effectiveness in the other 4 categories (pharmacological, supplements, complementary/alternative, and other interventions).

Conclusions: Overall, the interventions demonstrated mixed results in terms of effectiveness. All conclusions about effectiveness should be considered together with the methodological inadequacies of the studies. Interventions which have shown promising results include cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise therapy. Further research into these and other treatments is required using standardized outcome measures.

Introduction: Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) affects between 0.006% and 3% of the population depending on the criteria of definition used, with women being at higher risk than men.

Methods and outcomes: We conducted a systematic review and aimed to answer the following clinical question: What are the effects of treatments for chronic fatigue syndrome? We searched: Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library, and other important databases up to March 2010 (Clinical Evidence reviews are updated periodically; please check our website for the most up-to-date version of this review). We included harms alerts from relevant organisations such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Results: We found 46 systematic reviews, RCTs, or observational studies that met our inclusion criteria. We performed a GRADE evaluation of the quality of evidence for interventions.

Conclusions: In this systematic review we present information relating to the effectiveness and safety of the following interventions: antidepressants, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), corticosteroids, dietary supplements, evening primrose oil, galantamine, graded exercise therapy, homeopathy, immunotherapy, intramuscular magnesium, oral nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and prolonged rest.

Background: Throughout the world, patients with chronic diseases/illnesses use complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). The use of CAM is also substantial among patients with diseases/illnesses of unknown aetiology. Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also termed myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), is no exception. Hence, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of CAM treatments in patients with CFS/ME was undertaken to summarise the existing evidence from RCTs of CAM treatments in this patient population.

Methods: Seventeen data sources were searched up to 13th August 2011. All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any type of CAM therapy used for treating CFS were included, with the exception of acupuncture and complex herbal medicines; studies were included regardless of blinding. Controlled clinical trials, uncontrolled observational studies, and case studies were excluded.

Results: A total of 26 RCTs, which included 3,273 participants, met our inclusion criteria. The CAM therapy from the RCTs included the following: mind-body medicine, distant healing, massage, tuina and tai chi, homeopathy, ginseng, and dietary supplementation. Studies of qigong, massage and tuina were demonstrated to have positive effects, whereas distant healing failed to do so. Compared with placebo, homeopathy also had insufficient evidence of symptom improvement in CFS. Seventeen studies tested supplements for CFS. Most of the supplements failed to show beneficial effects for CFS, with the exception of NADH and magnesium.

Conclusions: The results of our systematic review provide limited evidence for the effectiveness of CAM therapy in relieving symptoms of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions concerning CAM therapy for CFS due to the limited number of RCTs for each therapy, the small sample size of each study and the high risk of bias in these trials. Further rigorous RCTs that focus on promising CAM therapies are warranted.

Background: There is no curative treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is widely used in the treatment of CFS in China.

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of TCM for CFS.

Methods: The protocol of this review is registered at PROSPERO. We searched six main databases for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on TCM for CFS from their inception to September 2013. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to assess the methodological quality. We used RevMan 5.1 to synthesize the results.

Results: 23 RCTs involving 1776 participants were identified. The risk of bias of the included studies was high. The types of TCM interventions varied, including Chinese herbal medicine, acupuncture, qigong, moxibustion, and acupoint application. The results of meta-analyses and several individual studies showed that TCM alone or in combination with other interventions significantly alleviated fatigue symptoms as measured by Chalder’s fatigue scale, fatigue severity scale, fatigue assessment instrument by Joseph E. Schwartz, Bell’s fatigue scale, and guiding principle of clinical research on new drugs of TCM for fatigue symptom. There was no enough evidence that TCM could improve the quality of life for CFS patients. The included studies did not report serious adverse events.

Conclusions: TCM appears to be effective to alleviate the fatigue symptom for people with CFS. However, due to the high risk of bias of the included studies, larger, well-designed studies are needed to confirm the potential benefit in the future.

Background: As the etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is unclear and the treatment is still a big issue. There exists a wide range of literature about acupuncture and moxibustion (AM) for CFS in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). But there are certain doubts as well in the effectiveness of its treatment due to the lack of a comprehensive and evidence-based medical proof to dispel the misgivings. Current study evaluated systematically the effectiveness of acupuncture and moxibustion treatments on CFS, and clarified the difference among them and Chinese herbal medicine, western medicine and sham-acupuncture.

Methods: We comprehensively reviewed literature including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CBM (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database) and CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) up to May 2016, for RCT clinical research on CFS treated by acupuncture and moxibustion. Traditional direct meta-analysis was adopted to analyze the difference between AM and other treatments. Analysis was performed based on the treatment in experiment and control groups. Network meta-analysis was adopted to make comprehensive comparisons between any two kinds of treatments. The primary outcome was total effective rate, while relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used as the final pooled statistics.

Results: A total of 31 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were enrolled in analyses. In traditional direct meta-analysis, we found that in comparison to Chinese herbal medicine, CbAM (combined acupuncture and moxibustion, which meant two or more types of acupuncture and moxibustion were adopted) had a higher total effective rate (RR (95% CI), 1.17 (1.09 ~ 1.25)). Compared with Chinese herbal medicine, western medicine and sham-acupuncture, SAM (single acupuncture or single moxibustion) had a higher total effective rate, with RR (95% CI) of 1.22 (1.14 ~ 1.30), 1.51 (1.31-1.74), 5.90 (3.64-9.56). In addition, compared with SAM, CbAM had a higher total effective rate (RR (95% CI), 1.23 (1.12 ~ 1.36)). In network meta-analyses, similar results were recorded. Subsequently, we ranked all treatments from high to low effective rate and the order was CbAM, SAM, Chinese herbal medicine, western medicine and sham-acupuncture.

Conclusions: In the treatment of CFS, CbAM and SAM may have better effect than other treatments. However, the included trials have relatively poor quality, hence high quality studies are needed to confirm our finding.

Objectives: This meta-analysis aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) in treating chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Methods: Nine electronic databases were searched from inception to May 2022. Two reviewers screened studies, extracted the data, and assessed the risk of bias independently. The meta-analysis was performed using the Stata 12.0 software. Results: Eighty-four RCTs that explored the efficacy of 69 kinds of Chinese herbal formulas with various dosage forms (decoction, granule, oral liquid, pill, ointment, capsule, and herbal porridge), involving 6,944 participants were identified. This meta-analysis showed that the application of CHM for CFS can decrease Fatigue Scale scores (WMD: -1.77; 95%CI: -1.96 to -1.57; p < 0.001), Fatigue Assessment Instrument scores (WMD: -15.75; 95%CI: -26.89 to -4.61; p < 0.01), Self-Rating Scale of mental state scores (WMD: -9.72; 95%CI:-12.26 to -7.18; p < 0.001), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale scores (WMD: -7.07; 95%CI: -9.96 to -4.19; p < 0.001), Self-Rating Depression Scale scores (WMD: -5.45; 95%CI: -6.82 to -4.08; p < 0.001), and clinical symptom scores (WMD: -5.37; 95%CI: -6.13 to -4.60; p < 0.001) and improve IGA (WMD: 0.30; 95%CI: 0.20-0.41; p < 0.001), IGG (WMD: 1.74; 95%CI: 0.87-2.62; p < 0.001), IGM (WMD: 0.21; 95%CI: 0.14-0.29; p < 0.001), and the effective rate (RR = 1.41; 95%CI: 1.33-1.49; p < 0.001). However, natural killer cell levels did not change significantly. The included studies did not report any serious adverse events. In addition, the methodology quality of the included RCTs was generally not high. Conclusion: Our study showed that CHM seems to be effective and safe in the treatment of CFS. However, given the poor quality of reports from these studies, the results should be interpreted cautiously. More international multi-centered, double-blinded, well-designed, randomized controlled trials are needed in future research.

What does all that tell us?

Disappointingly, it tells me that SCAM has preciously little to offer for ME/CFS patients.

But what about the TCM treatments? Aren’t the above reviews quite positive TCM?

Yes, they are but I nevertheless recommend taking them with a healthy pinch of salt.

Why?

Because we have seen many times before that, for a range of reasons, Chinese researchers of TCM draw false positive conclusions. That may sound unfair, harsh, or even racist, but I think it’s true. If you disagree, please show me a couple of systematic reviews of TCM for any human disease by Chinese researchers that have drawn negative conclusions.

And what is my advice to patients suffering from ME/CSF?

I think the best I can offer is this: be very cautious about the many claims made by SCAM enthusiasts; if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is!

Norbert Hofer is the former leader of the Austrian right-wing FPÖ party who almost became Austria’s President. Currently, he is the 3rd member of the National Council. Hofer is a man full of surprises; he stated, for instance, that the Quran was more dangerous than COVID-19 during a speech held at a 2020 campaign event. As a result, he was sued for hate-speech.

Hofer’s latest coup is not political but commercial: Hofer is launching his own dietary supplement on the market. It is called “Formula Fortuna” and contains:

- L-tryptophan; a Cochrane review concluded that “a large number of studies appear to address the research questions, but few are of sufficient quality to be reliable. Available evidence does suggest these substances are better than placebo at alleviating depression. Further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of 5‐HTP and tryptophan before their widespread use can be recommended. The possible association between these substances and the potentially fatal Eosinophilia‐Myalgia Syndrome has not been elucidated. Because alternative antidepressants exist which have been proven to be effective and safe the clinical usefulness of 5‐HTP and tryptophan is limited at present.”

- Hydroxypropylmethylcellulose, a common delivery system.

- Rhodiola rosea extracts; human studies evaluating R. rosea did not have sufficient quality to determine whether it has properties affecting fatigue or any other condition.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued warning letters to manufacturers of R. rosea dietary supplement products unapproved as new drugs, adulterated, misbranded and in federal violation for not having proof of safety or efficacy for the advertised conditions of alleviating Raynaud syndrome, altitude sickness, depression or cancer.

- Ginseng root extract. Although ginseng has been used in traditional medicine for centuries, modern research is inconclusive about its biological effects. Preliminary clinical research indicates possible effects on memory, fatigue, menopause symptoms, and insulin response in people with mild diabetes. Out of 44 studies examined between 2005–2015, 29 showed positive, limited evidence, and 15 showed no effects. As of 2021, there is insufficient evidence to indicate that ginseng has any health effects. A 2021 review indicated that ginseng had “only trivial effects on erectile function or satisfaction with intercourse compared to placebo”. The constituents include steroid saponins known as ginsenosides, but the effects of these ginseng compounds have not been studied with high-quality clinical research as of 2021, and therefore remain unknown. As of 2019, the United States FDA and Federal Trade Commission have issued numerous warning letters to manufacturers of ginseng dietary supplements for making false claims of health or anti-disease benefits, stating that the “products are not generally recognized as safe and effective for the referenced uses” and are illegal as unauthorized “new drugs” under federal law. Concerns exist when ginseng is used chronically, potentially causing side effects such as headaches, insomnia, and digestive problems. Ginseng may have adverse effects when used with the blood thinner warfarin. Ginseng also has adverse drug reactions with phenelzine, and a potential interaction has been reported with imatinib, resulting in hepatotoxicity, and with lamotrigine. Other side effects may include anxiety, insomnia, fluctuations in blood pressure, breast pain, vaginal bleeding, nausea, or diarrhea.

- Zinc gluconate which has been used in lozenges for treating the common cold. However, controlled trials with lozenges which include zinc acetate have found it has the greatest effect on the duration of coldsInstances of anosmia (loss of smell) have been reported with intranasal use of some products containing zinc gluconate. In September 2003, Zicam faced lawsuits from users who claimed that the product, a nasal gel containing zinc gluconate and several inactive ingredients, negatively affected their sense of smell and sometimes taste. Some plaintiffs alleged experiencing a strong and very painful burning sensation when they used the product. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc., the maker of Zicam, responded that only a small number of people had experienced problems and that anosmia can be caused by the common cold itself. In January 2006, 340 lawsuits were settled for $12 million.

- Pyridoxine hydrochloride (vitamin B6) is usually well tolerated, though overdose toxicity is possible. Occasionally side effects include headache, numbness, and sleepiness. Pyridoxine overdose can cause a peripheral sensory neuropathy characterized by poor coordination, numbness, and decreased sensation to touch, temperature, and vibration.

‘Formula Fortuna’ allegedly is for lifting your mood. If I, however, tell you that you need to pay one Euro per day for the supplement, your mood might even change in the opposite direction.

What next?

I think I might design a dietary supplement against stupidity. It will not carry any of the risks of Hofer’s new invention but, I am afraid, it might be just as ineffective as Hofer’s ‘Formual Fortuna’.

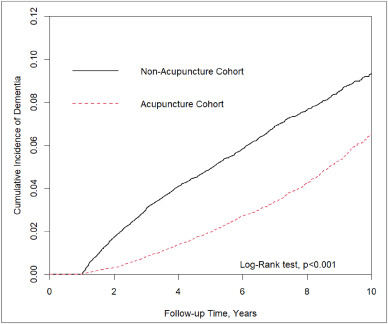

In this retrospective matched-cohort study, Chinese researchers investigated the association of acupuncture treatment for insomnia with the risk of dementia. They collected data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan to analyze the incidence of dementia in patients with insomnia who received acupuncture treatment.

The study included 152,585 patients, selected from the NHIRD, who were newly diagnosed with insomnia between 2000 and 2010. The follow-up period ranged from the index date to the date of dementia diagnosis, date of withdrawal from the insurance program, or December 31, 2013. A 1:1 propensity score method was used to match an equal number of patients (N = 18,782) in the acupuncture and non-acupuncture cohorts. The researchers employed Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the risk of dementia. The cumulative incidence of dementia in both cohorts was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the difference between them was assessed through a log-rank test.

Patients with insomnia who received acupuncture treatment were observed to have a lower risk of dementia (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.54, 95% confidence interval = 0.50–0.60) than those who did not undergo acupuncture treatment. The cumulative incidence of dementia was significantly lower in the acupuncture cohort than in the non-acupuncture cohort (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

The researchers concluded that acupuncture treatment significantly reduced or slowed the development of dementia in patients with insomnia.

They could be correct, of course. But, then again, they might not be. Nobody can tell!

As many who are reading these lines know: CORRELATION IS NOT CAUSATION.

But if acupuncture was not the cause for the observed differences, what could it be? After all, the authors used clever statistics to make sure the two groups were comparable!

The problem here is, of course, that they can only make the groups comparable for variables that were measured. These were about 20 parameters mostly related to medication intake and concomitant diseases. This leaves a few hundred potentially relevant variables that were not quantified and could thus not be accounted for.

My bet would be lifestyle: it is conceivable that the acupuncture group had acupuncture because they were generally more health-conscious. Living a relatively healthy life might reduce the dementia risk entirely unrelated to acupuncture. According to Occam’s razor, this explanation is miles more likely that the one about acupuncture.

So, what this study really demonstrates or implies is, I think, this:

- The propensity score method can never be perfect in generating completely comparable groups.

- The JTCM publishes rubbish.

- Correlation is not causation.

- To establish causation in clinical medicine, RCTs are usually the best option.

- Occam’s razor can be useful when interpreting research findings.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) combined with Western medicine (WM) in comparison with WM in reducing systolic and diastolic blood pressure for patients with primary hypertension (PHTN).

Various literature searches located a total of 29 studies that included 2623 patients. The results showed that the clinical effectiveness in the treatment of hypertension with CHM+WM was considerably higher than that with WM alone, clinical effective (RR 1.23, 95% CI [1.17, 1.30], P < 0.00001), and markedly effective (ME) in the patients (RR 1.66, 95% CI [1.52, 1.80], and P < 0.00001). Random effect in SBP (MD 7.91 mmHg,[6.00, 983], P < 0.00001) and DBP (MD 5.46 mmHg, [3.88, 6.43], P < 0.00001), a subgroup analysis was carried out based on the type of intervention, duration of treatment, and CHM formulas that showed significance. Furthermore, no severe side effects were reported, and no patients stopped treatment or withdrawal due to any severe adverse events.

The authors concluded that compared to WM alone, the therapeutic effectiveness of CHM combined with WM is significantly improved in the treatment of hypertension. Additionally, CHM with WM may safely and efficiently lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in individuals with PHTN. However, rigorous randomized controlled trials with a large sample, high quality, long duration of treatment, and follow-up are recommended to strengthen this clinical evidence.

The authors can boast of an impressive list of affiliations:

- 1Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, 150040, Heilongjiang, China; School of Pharmacy, Lebanese International University, 18644, Sana’a, Yemen.

- 2Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, 150040, Heilongjiang, China.

- 3Key Laboratory of Chinese Materia Medica, Ministry of Education of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, 150040, Heilongjiang, China.

- 4Department of Urology, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao Binhai University, Qingdao, Shandong, China.

- 5Department of Respiratory Diseases, Shandong Second Provincial General Hospital, Shandong University, Shandong, China.

- 6Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, 150040, Heilongjiang, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

Impressive in the sense of being impressively prone to bias, particularly knowing that ~80% of Chinese research findings have been shown to be fabricated and considering that Chinese authors as good as never publish anything negative about TCM.

But perhaps you still believe that the results reported here are 100% true? In this case, I might even agree with you. The reason is that the authors demonstrate in exemplary fashion what I have been saying so often before:

Blood pressure is one of the many endpoints that are highly prone to placebo effects. Therefore, even the addition of an ineffective CHM to WM would lower blood pressure more effectively than WM alone.

But there is a third way of explaining the findings of this review: some herbal remedies might actually have a hypotensive effect. The trouble is that this review does come not even close to telling us which.