systematic review

In one of my last posts, I was rather dismissive of veterinary chiropractic.

Was I too harsh?

I did ask readers who disagree with my judgment to send me their evidence.

Sadly, none arrived!

Therefore, I did several further literature searches and found a recent review of the topic. It included 14 studies; 13 were equine and one was a canine study. Seven of these were cohort studies and seven were randomized controlled clinical trials. . Study quality was low (n = 4), moderate (n = 7), and high (n = 3) and included a wide array of outcome parameters with varying levels of efficacy and duration of therapeutic effects, which prevented further meta-analysis. The authors concluded that it was difficult to draw firm conclusions despite all studies reporting positive effects. Optimal technique indications and dosages need to be determined to improve the standardization of these treatment options.

This, I think, can hardly be called good evidence. But I also found this more recent paper:

Chiropractic care is a common treatment modality used in equine practice to manage back pain and stiffness but has limited evidence for treating lameness. The objective of this blinded, controlled clinical trial was to evaluate the effect of chiropractic treatment on chronic lameness and concurrent axial skeleton pain and dysfunction. Two groups of horses with multiple limb lameness (polo) or isolated hind limb lameness (Quarter Horses) were enrolled. Outcome measures included subjective and objective measures of lameness, spinal pain and stiffness, epaxial muscle hypertonicity, and mechanical nociceptive thresholds collected on days 0, 14, and 28. Chiropractic treatment was applied on days 0, 7, 14, and 21. No treatment was applied to control horses. Data was analyzed by a mixed model fit separately for each response variable (p < 0.05) and was examined within each group of horses individually. Significant treatment effects were noted in subjective measures of hind limb and whole-body lameness scores and vertebral stiffness. Limited or inconsistent therapeutic effects were noted in objective lameness scores and other measures of axial skeleton pain and dysfunction. The lack of pathoanatomical diagnoses, multilimb lameness, and lack of validated outcome measures likely had negative impacts on the results.

Great! So, we finally have an RCT of chiropractic for horses. Unfortunately, the study is less than convincing:

- It included just 20 polo horses plus 18 horses active in ridden or competitive work all suffering from lameness.

- The authors state that ‘horses were numerically randomized to treatment and control groups’; yet I am not sure what this means.

- Treatment consisted of high-velocity, low-amplitude, manually applied thrusts to sites of perceived pain or stiffness with the axial and appendicular articulations. Treatment was applied on days 0, 7, 14, and 21 by a single examiner. The control group received no treatment and was restrained quietly for 15 min to simulate the time required for chiropractic treatment. In other words, no placebo controls were used.

- The validity of the many outcome measures is unknown.

- The statistical analyses seem odd to me.

- No correction for multiple statistical tests was done.

- Most of the outcomes show no significant effect.

- Overall, there were some small positive treatment effects based on subjective assessment of lameness, but no measurable treatment effects on objective measures of limb lameness.

- The polo horses began their competition season at the beginning of the study which would have confounded the outcomes.

What does all this tell us about veterinary chiropractic?

Not a lot.

All we can safely say, I think, is that veterinary chiropractic is not evidence-based and that claims to the contrary are certainly ill-informed and most probably of a promotional nature.

Konjac glucomannan (KGM), also just called ‘glucomannan’, is a dietary fiber hydro colloidal polysaccharide isolated from the tubers of Amorphophallus konjac. It is used as a food, a food additive, as well as a dietary supplement in many countries. KGM is claimed to reduce the levels of glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood pressure.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of the consumption of gummy candy enriched with KGM on appetite and to evaluate anthropometric data, biochemical, and oxidative stress markers in overweight individuals. Forty-two participants aged 18 to 45 years completed this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Participants were randomly assigned to consume for 14 days, 2 candies per day, containing 250 mg of KGM or identical-looking placebo candy with 250 mg of flaxseed meal, shortly after breakfast and dinner. As a result, we observed that there was a reduction in waist circumference and in the intensity of hunger of the participants who consumed KGM. The authors believe that a longer consumption time as well as an increased dose of KGM would contribute to even more satisfactory body results.

These findings seem promising, yet somehow I am not convinced. The study was small and short-term; moreover, the authors seem uncritical and, instead of a conclusion, they offer speculations.

Our own review of 2014 included 9 clinical studies. There was a variation in the reporting quality of the included RCTs. A meta-analysis (random effect model) of 8 RCTs revealed no significant difference in weight loss between glucomannan and placebo (mean difference [MD]: -0.22 kg; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.62, 0.19; I(2) = 65%). Adverse events included abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and constipation. We concluded that the evidence from available RCTs does not show that glucomannan intake generates statistically significant weight loss. Future trials should be more rigorous and better reported.

Rigorous trials are required to change my mind, and I am not sure that the new study falls into this category.

I have tried!

Honestly!

But at present, it is simply not possible to escape the revelations and accusations by Harry Windsor.

So, eventually, I gave in and had a look at the therapy he often refers to. He claims that he is deeply traumatized by what he had to go through and, to help him survive the ordeal, Harry has been reported to use EMDR.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a fringe psychotherapy that was developed to alleviate the distress associated with traumatic memories. It is supposed to facilitate the accessing and processing of traumatic memories and other adverse life experiences with a view of bringing these to an adaptive resolution. The claim is that, after successful treatment with EMDR therapy, affective distress is relieved, negative beliefs are reformulated, and physiological arousal is reduced.

During EMDR therapy the patient must attend to emotionally disturbing material in brief sequential doses while simultaneously focusing on an external stimulus. Therapist-directed lateral eye movements are commonly used as external stimulus but a variety of other stimuli including hand-tapping and audio stimulation can also be employed.

Francine Shapiro, the psychologist who invented EMDR claims to have serendipitously discovered this technique by experiencing spontaneous saccadic eye movements in response to disturbing thoughts during a walk in the woods. Yet, as GM Rosen explains, this explanation is difficult to accept because normal saccadic eye movements appear to be physiologically undetectable and are typically triggered by external stimuli.

Shapiro hypothesizes that EMDR therapy facilitates the access to the traumatic memory network, so that information processing is enhanced, with new associations forged between the traumatic memory and more adaptive memories or information. These new associations are alleged to result in complete information processing, new learning, elimination of emotional distress, and development of cognitive insights.

EMDR therapy uses a three-pronged protocol:

- (1) the past events that have laid the groundwork for dysfunction are processed, forging new associative links with adaptive information;

- (2) the current circumstances that elicit distress are targeted, and internal and external triggers are desensitized;

- (3) imaginal templates of future events are incorporated, to assist the client in acquiring the skills needed for adaptive functioning.

The question I ask myself is, of course: Does EMDR work?

The evidence is mixed and generally flimsy. A systematic review showed that “limitations to the current evidence exist, and much current evidence relies on small sample sizes and provides limited follow-up data”.

What might be particularly interesting in relation to Harry Windsor is that EMDR techniques have been associated with memory-undermining effects and may undermine the accuracy of memory, which can be risky if patients, later on, serve as witnesses in legal proceedings.

Personally, I think that Harry’s outbursts lend support to the hypothesis that EMDR is not effective. In the interest of the royal family, we should perhaps see whether so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) does offer an effective treatment against navel gazing?

This meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was aimed at evaluating the effects of massage therapy in the treatment of postoperative pain.

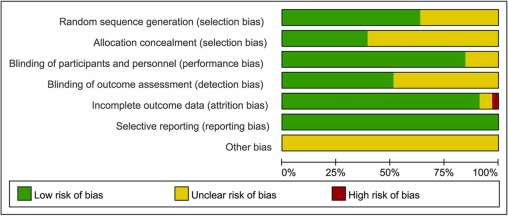

Three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) were searched for RCTs published from database inception through January 26, 2021. The primary outcome was pain relief. The quality of RCTs was appraised with the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool. The random-effect model was used to calculate the effect sizes and standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidential intervals (CIs) as a summary effect. The heterogeneity test was conducted through I2. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were used to explore the source of heterogeneity. Possible publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry.

The analysis included 33 RCTs and showed that MT is effective in reducing postoperative pain (SMD, -1.32; 95% CI, −2.01 to −0.63; p = 0.0002; I2 = 98.67%). A similarly positive effect was found for both short (immediate assessment) and long terms (assessment performed 4 to 6 weeks after the MT). Neither the duration per session nor the dose had a significant impact on the effect of MT, and there was no difference in the effects of different MT types. In addition, MT seemed to be more effective for adults. Furthermore, MT had better analgesic effects on cesarean section and heart surgery than orthopedic surgery.

The authors concluded that MT may be effective for postoperative pain relief. We also found a high level of heterogeneity among existing studies, most of which were compromised in the methodological quality. Thus, more high-quality RCTs with a low risk of bias, longer follow-up, and a sufficient sample size are needed to demonstrate the true usefulness of MT.

The authors discuss that publication bias might be possible due to the exclusion of all studies not published in English. Additionally, the included RCTs were extremely heterogeneous. None of the included studies was double-blind (which is, of course, not easy to do for MT). There was evidence of publication bias in the included data. In addition, there is no uniform evaluation standard for the operation level of massage practitioners, which may lead to research implementation bias.

Patients who have just had an operation and are in pain are usually thankful for the attention provided by carers. It might thus not matter whether it is provided by a massage or other therapist. The question is: does it matter? For the patient, it probably doesn’t; However, for making progress, it does, in my view.

In the end, we have to realize that, with clinical trials of certain treatments, scientific rigor can reach its limits. It is not possible to conduct double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of MT. Thus we can only conclude that, for some indications, massage seems to be helpful (and almost free of adverse effects).

This is also the conclusion that has been drawn long ago in some countries. In Germany, for instance, where I trained and practiced in my younger years, Swedish massage therapy has always been an accepted, conventional form of treatment (while exotic or alternative versions of massage therapy had no place in routine care). And in Vienna where I was chair of rehab medicine I employed about 8 massage therapists in my department.

Animals cannot consent to the treatments they are given when ill. This renders the promotion and use of SCAM in animals a tricky issue. This systematic review assessed the evidence for the clinical efficacy of 24 so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs) used in cats, dogs, and horses.

A bibliographic search, restricted to studies in cats, dogs, and horses, was performed on Web of Science Core Collection, CABI, and PubMed. Relevant articles were assessed for scientific quality, and information was extracted on study characteristics, species, type of treatment, indication, and treatment effects.

Of 982 unique publications screened, 42 were eligible for inclusion, representing 9 different SCAM therapies, which were

- aromatherapy,

- gold therapy,

- homeopathy,

- leeches (hirudotherapy),

- mesotherapy,

- mud,

- neural therapy,

- sound (music) therapy,

- vibration therapy.

For 15 predefined therapies, no study was identified. The risk of bias was assessed as high in 17 studies, moderate to high in 10, moderate in 10, low to moderate in four, and low in one study. In those studies where the risk of bias was low to moderate, there was considerable heterogeneity in reported treatment effects.

The authors concluded that the present systematic review has revealed significant gaps in scientific knowledge regarding the effects of a number of “miscellaneous” SCAM methods used in cats, dogs, and horses. For the majority of the therapies, no relevant scientific articles were retrieved. For nine therapies, some research documentation was available. However, due to small sample sizes, a lack of control groups, and other methodological limitations, few articles with a low risk of bias were identified. Where beneficial results were reported, they were not replicated in other independent studies. Many of the articles were in the lower levels of the evidence pyramid, emphasising the need for more high-quality research using precise methodologies to evaluate the potential therapeutic effects of these therapies. Of the publications that met the inclusion criteria, the majority did not have any scientific documentation of sufficient quality to draw any conclusion regarding their effect. Several of our observations may be translated into lessons on how to improve the scientific support for SCAM therapies. Crucial efforts include (a) a focus on the evaluation of therapies with an explanatory model for a mechanism of action accepted by the scientific community at large, (b) the use of appropriate control animals and treatments, preferably in randomized controlled trials, (c) high-quality observational studies with emphasis on control for confounding factors, (d) sufficient statistical power; to achieve this, large-scale multicenter trials may be needed, (e) blinded evaluations, and (f) replication studies of therapies that have shown promising results in single studies.

What the authors revealed in relation to homeopathy was particularly interesting, in my view. The included studies, with moderate risk of bias, such as homeopathic hypotensive treatment in dogs with early, stage two heart failure and the study on cats with hyperthyroidism, showed no differences between treated and non-treated animals. An RCT with osteoarthritic dogs showed a difference in three of the six variables (veterinary-assessed mobility, two force plate variables, an owner-assessed chronic pain index, and pain and movement visually analogous scales).

The results on homeopathy are supported by another systematic review of 18 RCTs, representing four species (including two dog studies) and 11 indications. The authors excluded generalized conclusions about the effect of certain homeopathic remedies or the effect of individualized homeopathy on a given medical condition in animals. In addition, a meta-analysis of nine homeopathy trials with a high risk of bias, and two studies with a lower risk of bias, concluded that there is very limited evidence that clinical intervention in animals using homeopathic remedies can be distinguished from similar placebo interventions.

In essence, this review confirms what I have been pointing out numerous times: SCAM for animals is not evidence-based, and this includes in particular homeopathy. It follows that its use in animals as an alternative to treatments with proven effectiveness borders on animal abuse.

It’s again the season for nine lessons, I suppose. So, on the occasion of Christmas Eve, let me rephrase the nine lessons I once gave (with my tongue firmly lodged in my cheek) to those who want to make a pseudo-scientific career in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) research.

- Throw yourself into qualitative research. For instance, focus groups are a safe bet. They are not difficult to do: you gather 5 -10 people, let them express their opinions, record them, extract from the diversity of views what you recognize as your own opinion and call it a ‘common theme’, and write the whole thing up, and – BINGO! – you have a publication. The beauty of this approach is manifold:

-

- you can repeat this exercise ad nauseam until your publication list is of respectable length;

- there are plenty of SCAM journals that will publish your articles;

- you can manipulate your findings at will;

- you will never produce a paper that displeases the likes of King Charles;

- you might even increase your chances of obtaining funding for future research.

- Conduct surveys. They are very popular and highly respected/publishable projects in SCAM. Do not get deterred by the fact that thousands of similar investigations are already available. If, for instance, there already is one describing the SCAM usage by leg-amputated policemen in North Devon, you can conduct a survey of leg-amputated policemen in North Devon with a medical history of diabetes. As long as you conclude that your participants used a lot of SCAMs, were very satisfied with it, did not experience any adverse effects, thought it was value for money, and would recommend it to their neighbour, you have secured another publication in a SCAM journal.

- In case this does not appeal to you, how about taking a sociological, anthropological or psychological approach? How about studying, for example, the differences in worldviews, the different belief systems, the different ways of knowing, the different concepts about illness, the different expectations, the unique spiritual dimensions, the amazing views on holism – all in different cultures, settings or countries? Invariably, you must, of course, conclude that one truth is at least as good as the next. This will make you popular with all the post-modernists who use SCAM as a playground for enlarging their publication lists. This approach also has the advantage to allow you to travel extensively and generally have a good time.

- If, eventually, your boss demands that you start doing what (in his narrow mind) constitutes ‘real science’, do not despair! There are plenty of possibilities to remain true to your pseudo-scientific principles. Study the safety of your favourite SCAM with a survey of its users. You simply evaluate their experiences and opinions regarding adverse effects. But be careful, you are on thin ice here; you don’t want to upset anyone by generating alarming findings. Make sure your sample is small enough for a false negative result, and that all participants are well-pleased with their SCAM. This might be merely a question of selecting your patients wisely. The main thing is that your conclusions do not reveal any risks.

- If your boss insists you tackle the daunting issue of SCAM’s efficacy, you must find patients who happened to have recovered spectacularly well from a life-threatening disease after receiving your favourite form of SCAM. Once you have identified such a person, you detail her experience and publish this as a ‘case report’. It requires a little skill to brush over the fact that the patient also had lots of conventional treatments, or that her diagnosis was never properly verified. As a pseudo-scientist, you will have to learn how to discretely make such details vanish so that, in the final paper, they are no longer recognisable.

- Your boss might eventually point out that case reports are not really very conclusive. The antidote to this argument is simple: you do a large case series along the same lines. Here you can even show off your excellent statistical skills by calculating the statistical significance of the difference between the severity of the condition before the treatment and the one after it. As long as this reveals marked improvements, ignores all the many other factors involved in the outcome and concludes that these changes are the result of the treatment, all should be tickety-boo.

- Your boss might one day insist you conduct what he narrow-mindedly calls a ‘proper’ study; in other words, you might be forced to bite the bullet and learn how to do an RCT. As your particular SCAM is not really effective, this could lead to serious embarrassment in the form of a negative result, something that must be avoided at all costs. I, therefore, recommend you join for a few months a research group that has a proven track record in doing RCTs of utterly useless treatments without ever failing to conclude that it is highly effective. In other words, join a member of my ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME. They will teach you how to incorporate all the right design features into your study without the slightest risk of generating a negative result. A particularly popular solution is to conduct a ‘pragmatic’ trial that never fails to produce anything but cheerfully positive findings.

- But even the most cunningly designed study of your SCAM might one day deliver a negative result. In such a case, I recommend taking your data and running as many different statistical tests as you can find; chances are that one of them will produce something vaguely positive. If even this method fails (and it hardly ever does), you can always focus your paper on the fact that, in your study, not a single patient died. Who would be able to dispute that this is a positive outcome?

- Now that you have grown into an experienced pseudo-scientist who has published several misleading papers, you may want to publish irrefutable evidence of your SCAM. For this purpose run the same RCT over again, and again, and again. Eventually, you want a meta-analysis of all RCTs ever published (see examples here and here). As you are the only person who conducted studies on the SCAM in question, this should be quite easy: you pool the data of all your dodgy trials and, bob’s your uncle: a nice little summary of the totality of the data that shows beyond doubt that your SCAM works and is safe.

When I conduct my regular literature searches, I am invariably delighted to find a paper that shows the effectiveness of a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Contrary to the impression that I might give to some, I like positive results as much as the next person. So, today you find me pleased to yet again report about one of my favorite SCAMs.

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) in breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) patients.

In total, 11 RCTs involving 1564 patients could be included, and 10 trials were deemed viable for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Due to the effects of MLD for BCRL, statistically significant improvements were found on the incidence of lymphedema (RR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.37, 0.93], P =.02) and pain intensity (SMD = -0.72, 95% CI [-1.34, -0.09], P = .02). Besides, the meta-analysis carried out implied that the effects that MLD had on volumetric changes of lymphedema and quality of life, were not statistically significant.

The authors concluded that the current evidence based on the RCTs shows that pain of BCRL patients undergoing MLD is significantly improved, while our findings do not support the use of MLD in improving volumetric of lymphedema and quality of life. Note that the effect of MLD for preventing BCRL is worthy of discussion.

Lymph drainage is so well-established in cancer care that most people would probably consider it a conventional treatment. If, however, you read for which conditions its inventor, Emil Vodder, used to promote it, they might change their minds. Vodder saw it as a cure for most illnesses, even those for which there is no plausibility or good evidence.

As far as I can see, lymph drainage works well for reducing lymph edema but, for all other conditions, it is not evidence-based. And this is the reason why I still categorize it as a SCAM.

The purpose of this review was to

- identify and map the available evidence regarding the effectiveness and harms of spinal manipulation and mobilisation for infants, children and adolescents with a broad range of conditions;

- identify and synthesise policies, regulations, position statements and practice guidelines informing their clinical use.

Two reviewers independently screened and selected the studies, extracted key findings and assessed the methodological quality of included papers. A descriptive synthesis of reported findings was undertaken using a level-of-evidence approach.

Eighty-seven articles were included. Their methodological quality varied. Spinal manipulation and mobilisation are being utilised clinically by a variety of health professionals to manage paediatric populations with

- adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS),

- asthma,

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),

- autism spectrum disorder (ASD),

- back/neck pain,

- breastfeeding difficulties,

- cerebral palsy (CP),

- dysfunctional voiding,

- excessive crying,

- headaches,

- infantile colic,

- kinetic imbalances due to suboccipital strain (KISS),

- nocturnal enuresis,

- otitis media,

- torticollis,

- plagiocephaly.

The descriptive synthesis revealed: no evidence to explicitly support the effectiveness of spinal manipulation or mobilisation for any condition in paediatric populations. Mild transient symptoms were commonly described in randomised controlled trials and on occasion, moderate-to-severe adverse events were reported in systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials and other lower-quality studies. There was strong to very strong evidence for ‘no significant effect’ of spinal manipulation for managing

- asthma (pulmonary function),

- headache,

- nocturnal enuresis.

There was inconclusive or insufficient evidence for all other conditions explored. There is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding spinal mobilisation to treat paediatric populations with any condition.

The authors concluded that, whilst some individual high-quality studies demonstrate positive results for some conditions, our descriptive synthesis of the collective findings does not provide support for spinal manipulation or mobilisation in paediatric populations for any condition. Increased reporting of adverse events is required to determine true risks. Randomised controlled trials examining effectiveness of spinal manipulation and mobilisation in paediatric populations are warranted.

Perhaps the most important findings of this review relate to safety. They confirm (yet again) that there is only limited reporting of adverse events in this body of research. Six reviews, eight RCTs and five other studies made no mention of adverse events or harms associated with spinal manipulation. This, in my view, amounts to scientific misconduct. Four systematic reviews focused specifically on adverse events and harms. They revealed that adverse events ranged from mild to severe and even death.

In terms of therapeutic benefit, the review confirms the findings from the previous research, e.g.:

- Green et al (Green S, McDonald S, Murano M, Miyoung C, Brennan S. Systematic review of spinal manipulation in children: review prepared by Cochrane Australia for Safer Care Victoria. Melbourne, Victoria: Victorian Government 2019. p. 1–67.) explored the effectiveness and safety of spinal manipulation and showed that spinal manipulation should – due to a lack of evidence and potential risk of harm – be recommended as a treatment of headache, asthma, otitis media, cerebral palsy, hyperactivity disorders or torticollis.

- Cote et al showed that evidence is lacking to support the use of spinal manipulation to treat non-musculoskeletal disorders.

In terms of risk/benefit balance, the conclusion could thus not be clearer: no matter whether chiropractors, osteopaths, physiotherapists, or any other healthcare professionals propose to manipulate the spine of your child, DON’T LET THEM DO IT!

This Cochrane review assessed the effectiveness and safety of oral homeopathic medicinal products compared with placebo or conventional therapy to prevent and treat acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) in children.

The researchers included double‐blind randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or double‐blind cluster‐RCTs comparing oral homeopathy medicinal products with placebo or self‐selected conventional treatments to prevent or treat ARTIs in children aged 0 to 16 years.

In this 2022 update, the researchers identified three new RCTs involving 251 children, for a total of 11 included RCTs with 1813 children receiving oral homeopathic medicinal products or a control treatment for ARTIs. All studies focused on upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), with only one study including some lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs). Six RCTs examined the effect on URTI recovery, and five RCTs investigated the effect on preventing URTIs after one to four months of treatment. Two treatment and three prevention studies involved homeopaths individualizing treatment. The other studies used predetermined, non-individualized remedies. All studies involved highly diluted homeopathic medicinal products, with dilutions ranging from 1 x 10‐4 to 1 x 10‐200.

Several limitations to the included studies were identified, in particular methodological inconsistencies and high attrition rates, failure to conduct intention‐to‐treat analysis, selective reporting, and apparent protocol deviations. Three studies were classified as at high risk of bias in at least one domain, and many studies had additional domains with unclear risk of bias. Four studies received funding from homeopathy manufacturers; one study support from a non‐government organization; two studies government support; one study was co‐sponsored by a university; and three studies did not report funding support.

The authors concluded that the “pooling of five prevention and six treatment studies did not show any consistent benefit of homeopathic medicinal products compared to placebo on ARTI recurrence or cure rates in children. We assessed the certainty of the evidence as low to very low for the majority of outcomes. We found no evidence to support the efficacy of homeopathic medicinal products for ARTIs in children. Adverse events were poorly reported, and we could not draw conclusions regarding safety.”

____________________________

These findings are hardly surprising. Will they change the behavior of homeopaths who feel that

- children respond particularly well to homeopathy,

- ARTIs are conditions for which homeopathy is particularly effective?

I would not hold my breath!

The American Heart Association has issued a statement outlining research on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for heart failure. They found some SCAMs that work, some that don’t work, and some that are harmful.

Alternative therapies that may benefit people with heart failure include:

- Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA, fish oil) have the strongest evidence among complementary and alternative agents for clinical benefit in people with heart failure and may be used safely, in moderation, in consultation with their health care team. Omega-3 PUFA is associated with a lower risk of developing heart failure and, for those who already have heart failure, improvements in the heart’s pumping ability. There appears to be a dose-related increase in atrial fibrillation (an irregular heart rhythm), so doses of 4 grams or more should be avoided.

- Yoga and Tai Chi, in addition to standard treatment, may help improve exercise tolerance and quality of life and decrease blood pressure.

Meanwhile, some therapies were found to have harmful effects, such as interactions with common heart failure medications and changes in heart contraction, blood pressure, electrolytes and fluid levels:

- While low blood levels of vitamin D are associated with worse heart failure outcomes, supplementation hasn’t shown benefit and may be harmful when taken with heart failure medications such as digoxin, calcium channel blockers and diuretics.

- The herbal supplement blue cohosh, from the root of a flowering plant found in hardwood forests, might cause a fast heart rate called tachycardia, high blood pressure, chest pain and may increase blood glucose. It may also decrease the effect of medications taken to treat high blood pressure and Type 2 diabetes.

- Lily of the valley, the root, stems and flower of which are used in supplements, has long been used in mild heart failure because it contains active chemicals similar to, but less potent than, the heart failure medicine digoxin. It may be harmful when taken with digoxin by causing very low potassium levels, a condition known as hypokalemia. Lily of the valley also may cause irregular heartbeat, confusion and tiredness.

Other therapies have been shown as ineffective based on current data, or have mixed findings, highlighting the importance of patients having a discussion with a health care professional about any non-prescribed treatments:

- Routine thiamine supplementation isn’t shown to be effective for heart failure treatment unless someone has this specific nutrient deficiency.

- Research on alcohol varies, with some data showing that drinking low-to-moderate amounts (1 to 2 drinks per day) is associated with preventing heart failure, while habitual drinking or intake of higher amounts is toxic to the heart muscle and known to contribute to heart failure.

- There are mixed findings about vitamin E. It may have some benefit in reducing the risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, a type of heart failure in which the left ventricle is unable to properly fill with blood between heartbeats. However, it has also been associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in people with heart failure.

- Co-Q10, or coenzyme Q10, is an antioxidant found in small amounts in organ meats, oily fish and soybean oil, and commonly taken as a dietary supplement. Small studies show it may help improve heart failure class, symptoms and quality of life, however, it may interact with blood pressure lowering and anti-clotting medicines. Larger trials are needed to better understand its effects.

- Hawthorn, a flowering shrub, has been shown in some studies to increase exercise tolerance and improve heart failure symptoms such as fatigue. Yet it also has the potential to worsen heart failure, and there is conflicting research about whether it interacts with digoxin.

“Overall, more quality research and well-powered randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the risks and benefits of complementary and alternative medicine therapies for people with heart failure,” said Chow. “This scientific statement provides critical information to health care professionals who treat people with heart failure and may be used as a resource for consumers about the potential benefit and harm associated with complementary and alternative medicine products.”

____________________

No doubt, this assessment is a laudable attempt to inform patients responsibly. Personally, I am always a bit skeptical about such broad statements. SCAM encompasses some 400 different therapies, and I doubt that these can all be assessed in one single overview.

It is not difficult to find SCAMs that seem to have not been considered. Take this systematic review, for instance. It included 24 RCTs (n = 1314 participants) of 9 different mind-body interventions (MBI) types: Tai Chi (n = 7), yoga (n = 4), relaxation (n = 4), meditation (n = 2), acupuncture (n = 2), biofeedback (n = 2), stress management (n = 1), Pilates (n = 1), and reflexology (n = 1). Most (n = 22, 95.8%) reported small-to-moderate improvements in quality of life (14/14 studies), exercise capacity (8/9 studies), depression (5/5 studies), anxiety and fatigue (4/4 studies), blood pressure (3/5 studies), heart rate (5/6 studies), heart rate variability (7/9 studies), and B-type natriuretic peptide (3/4 studies). Studies ranged from 4 minutes to 26 weeks and group sizes ranged from 8 to 65 patients per study arm.

The authors concluded that, although wide variability exists in the types and delivery, RCTs of MBIs have demonstrated small-to-moderate positive effects on HF patients’ objective and subjective outcomes. Future research should examine the mechanisms by which different MBIs exert their effects.

Or take this systematic review of 38 RCTs of oral TCM remedies. The majority of the included trials were assessed to be of high clinical heterogeneity and poor methodological quality. The main results of the meta-analysis showed improvement in total MLHFQ score when oral Chinese herbal medicine plus conventional medical treatment (CMT) compared with CMT with or without placebo [MD = -5.71 (-7.07, -4.36), p < 0.01].

The authors concluded that there is some encouraging evidence of oral Chinese herbal medicine combined with CMT for the improvement of QoL in CHF patients. However, the evidence remains weak due to the small sample size, high clinical heterogeneity, and poor methodological quality of the included trials. Further, large sample size and well-designed trials are needed.

Don’t get me wrong: I am not saying that TCM remedies are a viable option – in fact, I very much doubt it – but I am saying that attempts to provide comprehensive overviews of all SCAMs are problematic, and that incomplete overviews are just that: incomplete.