systematic review

Today is the start of chiropractic awareness week 2022. On this occasion the BCA states most categorically: First and foremost, chiropractic is a statutorily regulated healthcare profession, supported by evidence, which offers a safe form of treatment for patients with a range of conditions. Here I am tempted to cite my friend Simon Singh:

THEY HAPPILY PROMOTE BOGUS TREATMENTS

I am, of course, particularly impressed by the BCA’s assurance of safety. In my view, the safety issue needs to be addressed more urgently than any other in the realm of chiropractic. So, to make a meaningful contribution to the current chiropractic awareness week, I conducted a few Medline searches to identify all publications of 2022 on chiropractic/spinal manipulation risks.

This is what I found:

Objective: Patients can be at risk of carotid artery dissection and ischemic stroke after cervical chiropractic manipulation. However, such risks are rarely reported and raising awareness can increase the safety of chiropractic manipulations.

Case report: We present two middle-aged patients with carotid artery dissection leading to ischemic stroke after receiving chiropractic manipulation in Foshan, Guangdong Province, China. Both patients had new-onset pain in their necks after receiving chiropractic manipulations. Excess physical force during chiropractic manipulation may present a risk to patients. Patient was administered with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator after radiological diagnoses. They were prescribed 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg daily for 3 months as dual antiplatelet therapy. There were no complications over the follow-up period.

Conclusion: These cases suggest that dissection of the carotid artery can occur as the result of chiropractic manipulations. Patients should be diagnosed and treated early to achieve positive outcomes. The safety of chiropractic manipulations should be increased by raising awareness about the potential risks.

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) still remains an underdiagnosed etiology of new-onset headache. Important risk factors include chiropractic manipulation (CM). We present a case of a 36-year-old Filipino woman who presented with severe bifrontal and postural headache associated with dizziness, vomiting, and doubling of vision. A cranial computed tomography scan was done which showed an acute subdural hematoma (SDH) at the interhemispheric area. Pain medications were given which afforded minimal relief. On history, the headaches occurred 2 weeks after cervical CM. Cranial and cervical magnetic resonance imaging revealed findings supportive of intracranial hypotension and neck trauma, respectively. The patient improved with conservative management. We found 12 articles on SIH and CM after a systematic review of literature. Eleven patients (90.9%) initially presented with orthostatic headache. Eight patients (66.7%) were initially treated conservatively but only 5 (62.5%) had complete recovery. Recovery was achieved within 14 days from start of supportive therapy. Among the 3 patients who failed conservative treatment, 2 underwent non-directed epidural blood patch and one required neurosurgical intervention. This report highlights that a thorough history is warranted in patients with new onset headache. A history of CM must be actively sought. The limited evidence from the case reports showed that patients with SIH and SDH but with normal neurologic examination and minor spinal pathology can be managed conservatively for less than 2 weeks. This review showed that conservative treatment in a closely monitored environment may be an appropriate first line treatment.

Introduction: Cranio-cervical artery dissection (CeAD) is a common cause of cerebrovascular events in young subjects with no clear treatment strategy established. We evaluated the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in CeAD patients treated with and without stent placement.

Methods: COMParative effectiveness of treatment options in cervical Artery diSSection (COMPASS) is a single high-volume center observational, retrospective longitudinal registry that enrolled consecutive CeAD patients over a 2-year period. Patients were ≥ 18 years of age with confirmed extra- or intracranial CeAD on imaging. Enrolled participants were followed for 1 year evaluating MACE as the primary endpoint.

Results: One-hundred ten patients were enrolled (age 53 ± 15.9, 56% Caucasian, and 50% male, BMI 28.9 ± 9.2). Grade I, II, III, and IV blunt vascular injury was noted in 16%, 33%, 19%, and 32%, respectively. Predisposing factors were noted in the majority (78%), including sneezing, carrying heavy load, chiropractic manipulation. Stent was placed in 10 (10%) subjects (extracranial carotid n = 9; intracranial carotid n = 1; extracranial vertebral n = 1) at the physician’s discretion along with medical management. Reasons for stent placement were early development of high-grade stenosis or expanding pseudoaneurysm. Stented patients experienced no procedural or in-hospital complications and no MACE between discharge and 1 year follow up. CeAD patients treated with medical management only had 14% MACE at 1 year.

Conclusion: In this single high-volume center cohort of CeAD patients, stenting was found to be beneficial, particularly with development of high-grade stenosis or expanding pseudoaneurysm. These results warrant confirmation by a randomized clinical trial.

Background: Manipulation and mobilisation for low back pain are presented in an evidence-based manner with regard to mechanisms of action, indications, efficacy, cost-effectiveness ratio, user criteria and adverse effects. Terms such as non-specific or specific are replaced by the introduction of “entities” related to possible different low back pain forms.

Efficacy: MM is effective for acute and chronic low back pain in terms of pain relief, recovery of function and relapse prevention. It is equally effective but less risky compared to other recommended therapies. MM can be used alone in acute cases and not only in the case of chronic low back pain where it is always and necessarily part of a multimodal therapy programme, especially in combination with activating measures. The users of MM should exclusively be physician specialists trained according to the criteria of the German Medical Association (Bundesärztekammer) with an additional competence in manual medicine or appropriately trained certified therapists. The application of MM follows all rules of Good Clinical Practice.

Adverse effects: Significant adverse effects of MM for low back pain are reported in the international literature with a frequency of 1 per 50,000 to 1 per 3.7 million applications, i.e. MM for low back pain is practically risk-free and safe if performed according to the rules of the European Training Requirements of the UEMS.

Studies have reported that mild adverse events (AEs) are common after manual therapy and that there is a risk of serious injury. We aimed to assess the safety of Chuna manipulation therapy (CMT), a traditional manual Korean therapy, by analysing AEs in patients who underwent this treatment. Patients who received at least one session of CMT between December 2009 and March 2019 at 14 Korean medicine hospitals were included. Electronic patient charts and internal audit data obtained from situation report logs were retrospectively analysed. All data were reviewed by two researchers. The inter-rater agreement was assessed using the Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and reliability analysis among hospitals was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. In total, 2,682,258 CMT procedures were performed in 289,953 patients during the study period. There were 50 AEs, including worsened pain (n = 29), rib fracture (n = 11), falls during treatment (n = 6), chest pain (n = 2), dizziness (n = 1), and unpleasant feeling (n = 1). The incidence of mild to moderate AEs was 1.83 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.36-2.39) per 100,000 treatment sessions, and that of severe AEs was 0.04 (95% CI 0.00-0.16) per 100,000 treatment sessions. Thus, AEs of any level of severity were very rare after CMT. Moreover, there were no instances of carotid artery dissection or spinal cord injury, which are the most severe AEs associated with manual therapy in other countries.

_______________________________

This is not too bad after all!

Five papers are clearly better than nothing.

What conclusions might be drawn from my mini-review?

I think it might be safe to say:

- There is not much but at least some research going on in this area.

- The risks of chiropractic/spinal manipulation are real and are being recognized.

- BUT NOT BY CHIROPRACTORS! The most remarkable feature of the 5 papers, I think, is that none originates from a chiropractic team.

Thus, allow me to make a suggestion to chiropractors worldwide: Instead of continuing with HAPPILY PROMOTING BOGUS TREATMENTS, what about using the ‘chiropractic awareness week’ to raise awareness of the urgent necessity to research the safety of your treatments?

Ginseng plants belong to the genus Panax and include:

- Panax ginseng (Korean ginseng),

- Panax notoginseng (South China ginseng),

- and Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng).

They are said to have a range of therapeutic activities, some of which could render ginseng a potential therapy for viral or post-viral infections. Ginseng has therefore been used to treat fatigue in various patient groups and conditions. But does it work for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also often called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)? This condition is a complex, little-understood, and often disabling chronic illness for which no curative or definitive therapy has yet been identified.

This systematic review aimed to assess the current state of evidence regarding ginseng for CFS. Multiple databases were searched from inception to October 2020. All data was extracted independently and in duplicates. Outcomes of interest included the effectiveness and safety of ginseng in patients with CFS.

A total of two studies enrolling 68 patients were deemed eligible: one randomized clinical trial and one prospective observational study. The certainty of evidence in the effectiveness outcome was low and moderate in both studies, while the safety evidence was very low as reported from one study.

The authors concluded that the study findings highlight a potential benefit of ginseng therapy in the treatment of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions due to limited clinical studies. The paucity of data warrants limited confidence. There is a need for future rigorous studies to provide further evidence.

To get a feeling of how good or bad the evidence truly is, we must of course look at the primary studies.

The prospective observational study turns out to be a mere survey of patients using all sorts of treatments. It included 155 subjects who provided information on fatigue and treatments at baseline and follow-up. Of these subjects, 87% were female and 79% were middle-aged. The median duration of fatigue was 6.7 years. The percentage of users who found a treatment helpful was greatest for coenzyme Q10 (69% of 13 subjects), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (65% of 17 subjects), and ginseng (56% of 18 subjects). Treatments at 6 months that predicted subsequent fatigue improvement were vitamins (p = .08), vigorous exercise (p = .09), and yoga (p = .002). Magnesium (p = .002) and support groups (p = .06) were strongly associated with fatigue worsening from 6 months to 2 years. Yoga appeared to be most effective for subjects who did not have unclear thinking associated with fatigue.

The second study investigated the effect of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) on chronic fatigue (CF) by various measurements and objective indicators. Participants were randomized to KRG or placebo group (1:1 ratio) and visited the hospital every 2 weeks while taking 3 g KRG or placebo for 6 weeks and followed up 4 weeks after the treatment. The fatigue visual analog score (VAS) declined significantly in each group, but there were no significant differences between the groups. The 2 groups also had no significant differences in the secondary outcome measurements and there were no adverse events. Sub-group analysis indicated that patients with initial fatigue VAS below 80 mm and older than 50 years had significantly greater reductions in the fatigue VAS if they used KRG rather than placebo. The authors concluded that KRG did not show absolute anti-fatigue effect but provided the objective evidence of fatigue-related measurement and the therapeutic potential for middle-aged individuals with moderate fatigue.

I am at a loss in comprehending how the authors of the above-named review could speak of evidence for potential benefit. The evidence from the ‘observational study’ is largely irrelevant for deciding on the effectiveness of ginseng, and the second, more rigorous study fails to show that ginseng has an effect.

So, is ginseng a promising treatment for ME?

I doubt it.

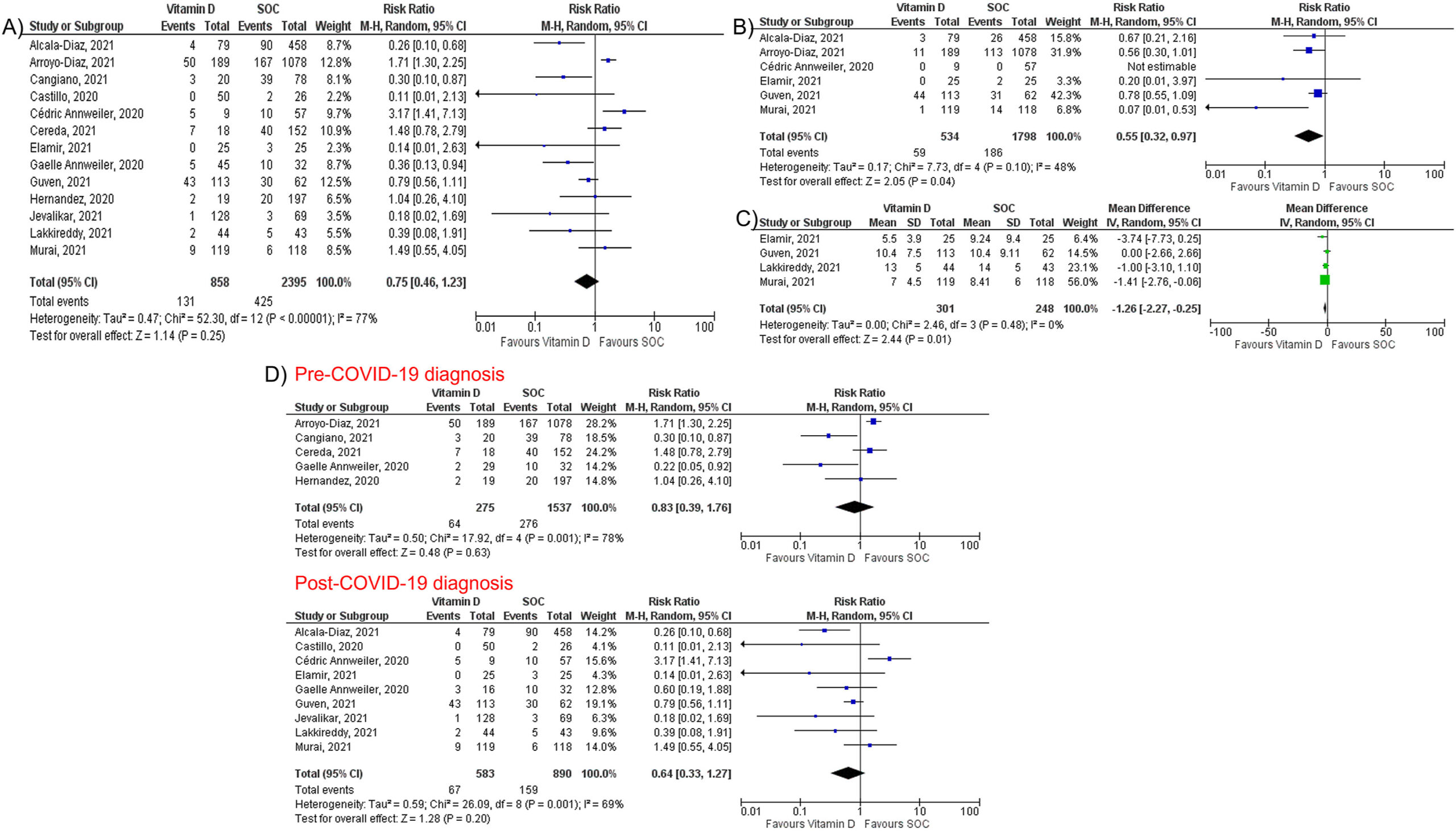

Micronutrient supplements such as vitamin D, vitamin C, and zinc have been used in managing viral illnesses. However, the clinical significance of these individual micronutrients in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains unclear. A team of researchers conducted this meta-analysis to provide a quantitative assessment of the clinical significance of these individual micronutrients in COVID-19.

They performed a literature search using MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane databases through December 5th, 2021. All individual micronutrients reported by ≥ 3 studies and compared with standard-of-care (SOC) were included. The primary outcome was mortality. The secondary outcomes were intubation rate and length of hospital stay (LOS). Pooled risk ratios (RR) and mean difference (MD) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the random-effects model.

The authors identified 26 studies (10 randomized controlled trials and 16 observational studies) involving 5633 COVID-19 patients that compared three individual micronutrient supplements (vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc) with SOC.

Vitamin C

Nine studies evaluated vitamin C in 1488 patients (605 in vitamin C and 883 in SOC). Vitamin C supplementation had no significant effect on mortality (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.62–1.62, P = 1.00), intubation rate (RR 1.77, 95% CI 0.56–5.56, P = 0.33), or LOS (MD 0.64; 95% CI -1.70, 2.99; P = 0.59).

Vitamin D

Fourteen studies assessed the impact of vitamin D on mortality among 3497 patients (927 in vitamin D and 2570 in SOC). Vitamin D did not reduce mortality (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.49–1.17, P = 0.21) but reduced intubation rate (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.32–0.97, P = 0.04) and LOS (MD -1.26; 95% CI -2.27, −0.25; P = 0.01). Subgroup analysis showed that vitamin D supplementation was not associated with a mortality benefit in patients receiving vitamin D pre or post COVID-19 diagnosis.

Zinc

Five studies, including 738 patients, compared zinc intake with SOC (447 in zinc and 291 in SOC). Zinc supplementation was not associated with a significant reduction of mortality (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.60–1.03, P = 0.08).

The authors concluded that individual micronutrient supplementations, including vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc, were not associated with a mortality benefit in COVID-19. Vitamin D may be associated with lower intubation rate and shorter LOS, but vitamin C did not reduce intubation rate or LOS. Further research is needed to validate our findings.

A multi-disciplinary research team assessed the effectiveness of interventions for acute and subacute non-specific low back pain (NS-LBP) based on pain and disability outcomes. For this purpose, they conducted a systematic review of the literature with network meta-analysis.

They included all 46 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving adults with NS-LBP who experienced pain for less than 6 weeks (acute) or between 6 and 12 weeks (subacute). Non-pharmacological treatments (eg, manual therapy) including acupuncture and dry needling or pharmacological treatments for improving pain and/or reducing disability considering any delivery parameters were included. The comparator had to be an inert treatment encompassing sham/placebo treatment or no treatment. The risk of bias was

- low in 9 trials (19.6%),

- unclear in 20 (43.5%),

- high in 17 (36.9%).

At immediate-term follow-up, for pain decrease, the most efficacious treatments against an inert therapy were:

- exercise (standardised mean difference (SMD) -1.40; 95% confidence interval (CI) -2.41 to -0.40),

- heat wrap (SMD -1.38; 95% CI -2.60 to -0.17),

- opioids (SMD -0.86; 95% CI -1.62 to -0.10),

- manual therapy (SMD -0.72; 95% CI -1.40 to -0.04).

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (SMD -0.53; 95% CI -0.97 to -0.09).

Similar findings were confirmed for disability reduction in non-pharmacological and pharmacological networks, including muscle relaxants (SMD -0.24; 95% CI -0.43 to -0.04). Mild or moderate adverse events were reported in the opioids (65.7%), NSAIDs (54.3%), and steroids (46.9%) trial arms.

The authors concluded that NS-LBP should be managed with non-pharmacological treatments which seem to mitigate pain and disability at immediate-term. Among pharmacological interventions, NSAIDs and muscle relaxants appear to offer the best harm-benefit balance.

The authors point out that previous published systematic reviews on spinal manipulation, exercise, and heat wrap did overlap with theirs: exercise (eg, motor control exercise, McKenzie exercise), heat wrap, and manual therapy (eg, spinal manipulation, mobilization, trigger points or any other technique) were found to reduce pain intensity and disability in adults with acute and subacute phases of NS-LBP.

I would add (as I have done so many times before) that the best approach must be the one that has the most favorable risk/benefit balance. Since spinal manipulation is burdened with considerable harm (as discussed so many times before), exercise and heat wraps seem to be preferable. Or, to put it bluntly:

if you suffer from NS-LBP, see a physio and not osteos or chiros!

You haven’t heard of religious/spiritual singing and movement as a treatment for mental health?

Me neither!

But it does exist. This review explored the evidence of religious/spiritual (R/S) singing and R/S movement (dynamic meditation and praise dance), in relation to mental health outcomes.

After registering with PROSPERO (CRD42020189495), a systematic search of three major databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO) was undertaken using predetermined eligibility criteria. Reference lists of identified papers and additional sources such as Google Scholar were searched. The quality of studies was assessed using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Data were extracted, tabulated, and synthesized according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines.

Seven of the 259 identified articles met inclusion criteria. Three studies considered R/S singing, while four considered R/S movement. In R/S movements, three studies considered dynamic meditation while one investigated praise dance. Although moderate to poor in quality, included studies indicated a positive trend for the effectiveness of R/S singing and movement in dealing with mental health concerns.

The authors concluded that, while R/S singing and R/S movement (praise dance and dynamic meditation) may be of value as mental health strategies, findings of the review need to be considered with caution due to methodological constraints. The limited number and poor quality of included studies highlight the need for further quality research in these R/S practices in mental health.

I am glad the authors caution us not to take their findings seriously. To be honest, I was not in danger of making this mistake. Neither do I feel the need for further research in this area. Mental health is a serious issue, and personally, I think we should research it not by conducting ridiculous studies of implausible modalities.

PS

I do not doubt that the experience of singing or movement can help in certain situations. However, I have my doubts about religious/spiritual singing and movement therapy.

Yes, Today is ‘WORLD SLEEP DAY‘ and you are probably in bed hoping this post will put you back to sleep.

This study aimed to synthesise the best available evidence on the safety and efficacy of using moxibustion and/or acupuncture to manage cancer-related insomnia (CRI).

The PRISMA framework guided the review. Nine databases were searched from its inception to July 2020, published in English or Chinese. Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) of moxibustion and or acupuncture for the treatment of CRI were selected for inclusion. The methodological quality was assessed using the method suggested by the Cochrane collaboration. The Cochrane Review Manager was used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Fourteen RCTs met the eligibility criteria; 7 came from China. Twelve RCTs used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score as continuous data and a meta-analysis showed positive effects of moxibustion and or acupuncture (n = 997, mean difference (MD) = -1.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) = -2.75 to -0.94, p < 0.01). Five RCTs using continuous data and a meta-analysis in these studies also showed significant difference between two groups (n = 358, risk ratio (RR) = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.26-0.80, I 2 = 39%).

The authors concluded that the meta-analyses demonstrated that moxibustion and or acupuncture showed a positive effect in managing CRI. Such modalities could be considered an add-on option in the current CRI management regimen.

Even at the risk of endangering your sleep, I disagree with this conclusion. Here are some of my reasons:

- Chinese acupuncture trials invariably are positive which means they are as reliable as a 4£ note.

- Most trials were of poor methodological quality.

- Only one made an attempt to control for placebo effects.

- Many followed the A+B versus B design which invariably produces (false-) positive results.

- Only 4 out of 14 studies mentioned adverse events which means that 10 violated research ethics.

Sorry to have disturbed your sleep!

This review assessed the magnitude of reporting bias in trials assessing homeopathic treatments and its impact on evidence syntheses.

A cross-sectional study and meta-analysis. Two persons independently searched Clinicaltrials.gov, the EU Clinical Trials Register and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform up to April 2019 to identify registered homeopathy trials. To determine whether registered trials were published and to detect published but unregistered trials, two persons independently searched PubMed, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Embase and Google Scholar up to April 2021. For meta-analyses, the authors used random effects models to determine the impact of unregistered studies on meta-analytic results.

The investigators reported the proportion of registered but unpublished trials and the proportion of published but unregistered trials. They also assessed whether primary outcomes were consistent between registration and publication

Since 2002, almost 38% of registered homeopathy trials have remained unpublished, and 53% of published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have not been registered. Retrospective registration was more common than prospective registration. Furthermore, 25% of primary outcomes were altered or changed compared with the registry. Although we could detect a statistically significant trend toward an increase of registrations of homeopathy trials (p=0.001), almost 30% of RCTs published during the past 5 years had not been registered.

A meta-analysis stratified by registration status of RCTs revealed substantially larger treatment effects of unregistered RCTs (SMD: −0.53, 95% CI −0.87 to −0.20) than registered RCTs (SMD: −0.14, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.07).

The authors concluded that registration of published trials was infrequent, many registered trials were not published and primary outcomes were often altered or changed. This likely affects the validity of the body of evidence of homeopathic literature and may overestimate the true treatment effect of homeopathic remedies.

An obvious investigation to do (why did I not have this idea?)!

And a finding that will surprise few (except fans of homeopathy who will, of course, dispute it).

The authors also mention that reporting biases are likely to have a substantial impact on the estimated treatment effect of homeopathy. Using data from a highly cited meta-analysis of homeopathy RCTs, our example showed that unregistered trials yielded substantially larger treatment effects than registered trials. They also caution that, because of the reporting biases identified in their analysis, effect estimates of meta-analyses of homeopathy trials might substantially overestimate the true treatment effect of homeopathic remedies and need to be interpreted cautiously.

In other words, the few reviews suggesting that homeopathy works beyond placebo (and are thus celebrated by homeopaths) are most likely false-positive. And the many reviews showing that homeopathy does not work would demonstrate this fact even clearer if the reporting bias had been accounted for.

Or, to put it bluntly:

The body of evidence on homeopathy is rotten to the core and therefore not reliable.

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is among the most common types of pain in adults. It is also the domain for many types of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). However, their effectiveness remains questionable, and the optimal approach to CLBP remains elusive. Meditation-based therapies constitute a form of SCAM with high potential for widespread availability.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of meditation-based therapies for CLBP management. The primary outcomes were pain intensity, quality of life, and pain-related disability; the secondary outcomes were the experienced distress or anxiety and pain bothersomeness in the patients. The PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases were searched for studies published from their inception until July 2021, without language restrictions.

A total of 12 randomized clinical trials with 1153 patients were included. In 10 trials, meditation-based therapies significantly reduced the CLBP pain intensity compared with nonmeditation therapies (standardized mean difference [SMD] -0.27, 95% CI = -0.43 to – 0.12, P = 0.0006). In 7 trials, meditation-based therapies also significantly reduced CLBP bothersomeness compared with nonmeditation therapies (SMD -0.21, 95% CI = -0.34 to – 0.08, P = 0.002). In 3 trials, meditation-based therapies significantly improved patient quality of life compared with nonmeditation therapies (SMD 0.27, 95% CI = 0.17 to 0.37, P < 0.00001).

The authors concluded that meditation-based therapies constitute a safe and effective alternative approach for CLBP management.

The problem with this conclusion is that the primary studies are mostly of poor quality. For instance, they do not control for placebo effects (which is obviously not easy in this case). Thus, we need to take the conclusion with a pinch of salt.

However, since the same limitations apply to chiropractic and osteopathy, and since meditation has far fewer risks than these approaches, I would gladly recommend meditation over manipulative therapies. Or, to put it plainly: in terms of risk/benefit balance, meditation seems preferable to spinal manipulation.

The new issue of the BMJ carries an article on acupuncture that cries out for a response. Here, I show you the original article followed by my short comments. For clarity, I have omitted the references from the article and added references that refer to my comments.

_________________________________________

Conventional allopathic medicine [1]—medications and surgery [2] used in conventional systems of medicine to treat or prevent disease [3]—is often expensive, can cause side effects and harm, and is not always the optimal treatment for long term conditions such as chronic pain [4]. Where conventional treatments have not been successful, acupuncture and other traditional and complementary medicines have potential to play a role in optimal patient care [5].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2019 global report, acupuncture is widely used across the world. [6] In some countries acupuncture is covered by health insurance and established regulations. [7] In the US, practitioners administer over 10 million acupuncture treatments annually. [6] In the UK, clinicians administer over 4 million acupuncture treatments annually, and it is provided on the NHS. [6]

Given the widespread use of acupuncture as a complementary therapy alongside conventional medicine, there has been an increase in global research interest and funding support over recent decades. In 2009, the European Commission launched a Good Practice in Traditional Chinese Medicine Research (GP-TCM) funding initiative in 19 countries. [7] The GP-TCM grant aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of acupuncture as well as other traditional Chinese medicine interventions.

In China, acupuncture is an important focus of the national research agenda and receives substantial research funding. [8] In 2016, the state council published a national strategy supporting universal access to acupuncture by 2020. China has established more than 79 evidence-based traditional Chinese medicine or integrative medicine research centers. [9]

Given the broad clinical application and rapid increase in funding support for acupuncture research, researchers now have additional opportunities to produce high-quality studies. However, for this to be successful, acupuncture research must address both methodological limitations and unique research challenges.

This new collection of articles, published in The BMJ, analyses the progress of developing high quality research studies on acupuncture, summarises the current status, and provides critical methodological guidance regarding the production of clinical evidence on randomised controlled trials, clinical practice guidelines and health economic evidence. It also assesses the number and quality of systematic reviews of acupuncture. [10] We hope that the collection will help inform the development of clinical practice guidelines, health policy, and reimbursement decisions. [11]

The articles document the progress of acupuncture research. In our view, the emerging evidence base on the use of acupuncture warrants further integration and application of acupuncture into conventional medicine. [12] National, regional, and international organisations and health systems should facilitate this process and support further rigorous acupuncture research.

Footnotes

This article is part of a collection funded by the special purpose funds for the belt and road, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Innovation Team and Talents Cultivation Program of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Special Project of “Lingnan Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine” of the 2019 Guangdong Key Research and Development Program, and the Project of First Class Universities and High-level Dual Discipline for Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The BMJ commissioned, peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish. Kamran Abbasi was the lead editor for The BMJ. Yu-Qing Zhang advised on commissioning for the collection, designed the topic of the series, and coordinated the author teams. Gordon Guyatt provided valuable advice and guidance. [13]

1. Allopathic medicine is the term Samuel Hahnemann coined for defaming conventional medicine. Using it in the first sentence of the article sets the scene very well.

2. Medicine is much more than ‘medications and surgery’. To imply otherwise is a strawman fallacy.

3. What about rehabilitation medicine?

4. ‘Conventional medicine is not always the optimal treatment’? This statement is very confusing and wrong. It is true that conventional medicine is not always effective. However, it is by definition the best we currently have and therefore it IS optimal.

5. Another fallacy: non sequitur

6. Another fallacy: appeal to popularity.

7. Yet another fallacy: appeal to authority.

8. TCM is heavily promoted by China not least because it is a most lucrative source of income.

9. Several research groups have shown that 100% of acupuncture research coming out of China report positive results. This casts serious doubt on the reliability of these studies (see, for instance, here, here, and here).

10. It has been noted that more than 80 percent of clinical data from China is fabricated.

11. Based on the points raised above, it seems to me that the collection’s aim is not to provide objective information but uncritical promotion.

12. I find it telling that the authors do not even consider the possibility that rigorous research might demonstrate that acupuncture cannot generate more good than harm.

13. This statement essentially admits that the series of articles constitutes paid advertising for TCM. The BMJ’s peer-review process must have been less than rigorous in this case.

Neurosurgeons from the Philippines recently presented the case of a 36-year-old woman who presented with severe bifrontal and postural headache associated with dizziness, vomiting, and double vision. A cranial computed tomography scan showed an acute subdural hematoma (SDH) at the interhemispheric area. Pain medications were given which afforded minimal relief.

The headaches occurred 2 weeks after the patient had received a cervical chiropractic manipulation (CM). Cranial and cervical magnetic resonance imaging revealed findings supportive of intracranial hypotension and neck trauma. The patient improved with conservative management.

The authors found 12 articles of SIH and CM after a systematic review of the literature. Eleven patients (90.9%) initially presented with orthostatic headaches. Eight patients (66.7%) were initially treated conservatively but only 5 (62.5%) had a complete recovery. Recovery was achieved within 14 days from the start of supportive therapy. Among the 3 patients who failed conservative treatment, 2 underwent non-directed epidural blood patch, and one required neurosurgical intervention.

The authors concluded that this report highlights that a thorough history is warranted in patients with new-onset headaches. A history of CM must be actively sought. The limited evidence from the case reports showed that patients with SIH and SDH but with normal neurologic examination and minor spinal pathology can be managed conservatively for less than 2 weeks. This review showed that conservative treatment in a closely monitored environment may be an appropriate first-line treatment.

As the authors rightly state, their case report does not stand alone. There are many more. In 2014, an Australian chiropractor published this review:

Background: Intracranial hypotension (IH) is caused by a leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (often from a tear in the dura) which commonly produces an orthostatic headache. It has been reported to occur after trivial cervical spine trauma including spinal manipulation. Some authors have recommended specifically questioning patients regarding any chiropractic spinal manipulation therapy (CSMT). Therefore, it is important to review the literature regarding chiropractic and IH.

Objective: To identify key factors that may increase the possibility of IH after CSMT.

Method: A systematic search of the Medline, Embase, Mantis and PubMed databases (from 1991 to 2011) was conducted for studies using the keywords chiropractic and IH. Each paper was reviewed to examine any description of the key factors for IH, the relationship or characteristics of treatment, and the significance of CSMT to IH. In addition, other items that were assessed included the presence of any risk factors, neck pain and headache.

Results: The search of the databases identified 39 papers that fulfilled initial search criteria, from which only eight case reports were relevant for review (after removal of duplicate papers or papers excluded after the abstract was reviewed). The key factors for IH (identified from the existing literature) were recent trauma, connective tissue disorders, or otherwise cases were reported as spontaneous. A detailed critique of these cases demonstrated that five of eight cases (63%) had non-chiropractic SMT (i.e. SMT technique typically used by medical practitioners). In addition, most cases (88%) had minimal or no discussion of the onset of the presenting symptoms prior to SMT and whether the onset may have indicated any contraindications to SMT. No case reports included information on recent trauma, changes in headache patterns or connective tissue disorders.

Discussion: Even though type of SMT often indicates that a chiropractor was not the practitioner that delivered the treatment, chiropractic is specifically cited as either the cause of IH or an important factor. There are so much missing data in the case reports that one cannot determine whether the practitioner was negligent (in clinical history taking) or whether the SMT procedure itself was poorly administered.

The new case report can, of course, be criticized for being not conclusive and for not allowing to firmly establish the cause of the adverse event. This is to a large extent due to the nature of case reports. Essentially, they provide a ‘signal’, and once the signal is loud enough, we need to act. In this case, action would mean to prohibit the intervention that is under suspicion and initiate conclusive research to prove or disprove a causal relationship.

This is how it’s done in most areas of healthcare … except, of course in so-called alternative medicine(SCAM). Here we do not even have the most basic tool to get to the bottom of the problem, namely a transparent post-marketing surveillance system that monitors the frequency of adverse events.

And whose responsibility is it to put such a system in place?

I let you guess.