pain

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is among the most common types of pain in adults. It is also the domain for many types of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). However, their effectiveness remains questionable, and the optimal approach to CLBP remains elusive. Meditation-based therapies constitute a form of SCAM with high potential for widespread availability.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of meditation-based therapies for CLBP management. The primary outcomes were pain intensity, quality of life, and pain-related disability; the secondary outcomes were the experienced distress or anxiety and pain bothersomeness in the patients. The PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases were searched for studies published from their inception until July 2021, without language restrictions.

A total of 12 randomized clinical trials with 1153 patients were included. In 10 trials, meditation-based therapies significantly reduced the CLBP pain intensity compared with nonmeditation therapies (standardized mean difference [SMD] -0.27, 95% CI = -0.43 to – 0.12, P = 0.0006). In 7 trials, meditation-based therapies also significantly reduced CLBP bothersomeness compared with nonmeditation therapies (SMD -0.21, 95% CI = -0.34 to – 0.08, P = 0.002). In 3 trials, meditation-based therapies significantly improved patient quality of life compared with nonmeditation therapies (SMD 0.27, 95% CI = 0.17 to 0.37, P < 0.00001).

The authors concluded that meditation-based therapies constitute a safe and effective alternative approach for CLBP management.

The problem with this conclusion is that the primary studies are mostly of poor quality. For instance, they do not control for placebo effects (which is obviously not easy in this case). Thus, we need to take the conclusion with a pinch of salt.

However, since the same limitations apply to chiropractic and osteopathy, and since meditation has far fewer risks than these approaches, I would gladly recommend meditation over manipulative therapies. Or, to put it plainly: in terms of risk/benefit balance, meditation seems preferable to spinal manipulation.

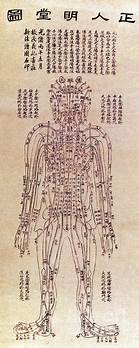

The new issue of the BMJ carries an article on acupuncture that cries out for a response. Here, I show you the original article followed by my short comments. For clarity, I have omitted the references from the article and added references that refer to my comments.

_________________________________________

Conventional allopathic medicine [1]—medications and surgery [2] used in conventional systems of medicine to treat or prevent disease [3]—is often expensive, can cause side effects and harm, and is not always the optimal treatment for long term conditions such as chronic pain [4]. Where conventional treatments have not been successful, acupuncture and other traditional and complementary medicines have potential to play a role in optimal patient care [5].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2019 global report, acupuncture is widely used across the world. [6] In some countries acupuncture is covered by health insurance and established regulations. [7] In the US, practitioners administer over 10 million acupuncture treatments annually. [6] In the UK, clinicians administer over 4 million acupuncture treatments annually, and it is provided on the NHS. [6]

Given the widespread use of acupuncture as a complementary therapy alongside conventional medicine, there has been an increase in global research interest and funding support over recent decades. In 2009, the European Commission launched a Good Practice in Traditional Chinese Medicine Research (GP-TCM) funding initiative in 19 countries. [7] The GP-TCM grant aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of acupuncture as well as other traditional Chinese medicine interventions.

In China, acupuncture is an important focus of the national research agenda and receives substantial research funding. [8] In 2016, the state council published a national strategy supporting universal access to acupuncture by 2020. China has established more than 79 evidence-based traditional Chinese medicine or integrative medicine research centers. [9]

Given the broad clinical application and rapid increase in funding support for acupuncture research, researchers now have additional opportunities to produce high-quality studies. However, for this to be successful, acupuncture research must address both methodological limitations and unique research challenges.

This new collection of articles, published in The BMJ, analyses the progress of developing high quality research studies on acupuncture, summarises the current status, and provides critical methodological guidance regarding the production of clinical evidence on randomised controlled trials, clinical practice guidelines and health economic evidence. It also assesses the number and quality of systematic reviews of acupuncture. [10] We hope that the collection will help inform the development of clinical practice guidelines, health policy, and reimbursement decisions. [11]

The articles document the progress of acupuncture research. In our view, the emerging evidence base on the use of acupuncture warrants further integration and application of acupuncture into conventional medicine. [12] National, regional, and international organisations and health systems should facilitate this process and support further rigorous acupuncture research.

Footnotes

This article is part of a collection funded by the special purpose funds for the belt and road, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Innovation Team and Talents Cultivation Program of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Special Project of “Lingnan Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine” of the 2019 Guangdong Key Research and Development Program, and the Project of First Class Universities and High-level Dual Discipline for Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The BMJ commissioned, peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish. Kamran Abbasi was the lead editor for The BMJ. Yu-Qing Zhang advised on commissioning for the collection, designed the topic of the series, and coordinated the author teams. Gordon Guyatt provided valuable advice and guidance. [13]

1. Allopathic medicine is the term Samuel Hahnemann coined for defaming conventional medicine. Using it in the first sentence of the article sets the scene very well.

2. Medicine is much more than ‘medications and surgery’. To imply otherwise is a strawman fallacy.

3. What about rehabilitation medicine?

4. ‘Conventional medicine is not always the optimal treatment’? This statement is very confusing and wrong. It is true that conventional medicine is not always effective. However, it is by definition the best we currently have and therefore it IS optimal.

5. Another fallacy: non sequitur

6. Another fallacy: appeal to popularity.

7. Yet another fallacy: appeal to authority.

8. TCM is heavily promoted by China not least because it is a most lucrative source of income.

9. Several research groups have shown that 100% of acupuncture research coming out of China report positive results. This casts serious doubt on the reliability of these studies (see, for instance, here, here, and here).

10. It has been noted that more than 80 percent of clinical data from China is fabricated.

11. Based on the points raised above, it seems to me that the collection’s aim is not to provide objective information but uncritical promotion.

12. I find it telling that the authors do not even consider the possibility that rigorous research might demonstrate that acupuncture cannot generate more good than harm.

13. This statement essentially admits that the series of articles constitutes paid advertising for TCM. The BMJ’s peer-review process must have been less than rigorous in this case.

Guest post by Catherine de Jong

On the 22nd of February 2022, a criminal court in the Netherlands ruled in a case brought by a 33-year-old man who suffered a double-sided vascular dissection of his vertebral arteries during a chiropractic neck manipulation.

What happened?

On the 26th of January 2016, the man visited a chiropractor because he wanted treatment for his headache. The chiropractor treated him with manipulations of his neck. The first treatment was uneventful but apparently not effective. The man went back for a second time. Immediately after the second treatment, the patient felt a tingling sensation that started in his toes and spread all over his body. Then he lost consciousness. He was resuscitated by the chiropractor and transported to a hospital. Several days later he woke up in the ICU of the university hospital (Free University, now Amsterdam UMC). He was paralyzed and unable to speak. He stayed in the ICU for 5 weeks. After a long stay in a rehabilitation center, he is now at home. He is disabled and incapacitated for life.

Court battles

The professional liability insurance of the chiropractor recognized that the treatment of the chiropractor had caused the disability and paid for damages. The patient was thus able to buy a new wheelchair-adapted house.

Health Inspection investigated the case. They noticed that the chiropractor could not show that there was informed consent for the neck manipulation treatment, but otherwise saw no need for action.

Six days after the accident the man applied to the criminal court. The case was dropped because, according to the judge, proof of guilt beyond reasonable doubt was impossible.

In rare occasions, vertebral artery dissection (VAD) does occur spontaneously in people without trauma or a chiropractor manipulating their neck. The list of causes for VAD show, besides severe trauma to the head and neck (traffic accidents) also chiropractic treatment, and rare connective tissue diseases like Marfan syndrome. A spontaneous dissection is very rare.

It took several attempts to persuade the criminal court to start the case and the investigation into what had happened in the chiropractor’s office. Now the verdict has been given, and it was a disappointing one.

The chiropractor was acquitted. The defense of the chiropractor argued, as expected, that two pre-existent spontaneous dissections might have caused the headache and that, therefore, the manipulation of the neck would have played at most a secondary role.

It is this defense strategy, which is invariably followed in the numerous court cases in the US. Chiropractors in particular give credence to this argumentation.

The defense of the patient was a professor of neurology. He considered a causal link between manipulation to the neck and the double-sided VAD to be proven.

In the judgment, the judge refers 14 times to the ‘professional standard’ of the Dutch Chiropractors Association, apparently without realizing that this professional standard was devised by the chiropractors themselves and that it differs considerably from the guidelines of neurologists or orthopedics. In 2016, the Dutch Health Inspection disallowed neck manipulation, but chiropractors do not care.

The verdict of the judge can be found here: ECLI:EN:RBNHO:2022:1401

Chiropractic is a profession that is not recognized in the Netherlands. Enough has been written (also on this website) about the strange belief of chiropractors that a wrong position of the vertebrae (“subluxations”) is responsible for 95% of all health problems and that detecting and correcting them can relieve symptoms and improve overall health. There is no scientific evidence that chiropractic subluxations exist or that their alleged “detection” or “correction” provides any health benefit. In the Netherlands, there are about 300 practicing chiropractors. Most are educated in the UK or the USA. The training that those chiropractors receive is not recognized in the Netherlands.

Most chiropractic treatments do little harm, but that does not apply to neck manipulation. When manipulating the neck, the outstretched head is subjected to powerful stretches and rotations. This treatment can in rare cases cause damage to the arteries, which carry blood to the brain. In this case, a double-sided cervical arterial dissection can lead to strokes and cerebral infarctions. How often this occurs (where is the central complication registration of chiropractors?) is unknown, but given that the effectiveness of this treatment has never been demonstrated and that therefore its risk/benefit ratio is negative, any complication is unacceptable.

How big is the chance that a 33-year-old man walks into a chiropractor’s office with a headache and comes out with a SPONTANEOUS double-sided vertebral artery dissection that leaves him wheelchair-bound and invalid for the rest of his life? I hope some clever statisticians will tell me.

PS

Most newspaper reports of this case are in Dutch, but here is one in English

Auriculotherapy (or ear acupuncture) is the use of electrical, mechanical, or other stimuli at specific points on the outer ear for therapeutic purposes. It was invented by the French neurologist Paul Nogier (1908–1996) who published his “Treatise of Auriculotherapy” in 1961. Auriculotherapy is based on the idea that the human outer ear is an area that reflects the entire body. Proponents of auriculotherapy refer to maps where our inner organs and body parts are depicted on the outer ear. These maps are not in line with our knowledge of anatomy and physiology. Auriculotherapy thus lacks plausibility.

This single-blind randomized, placebo-controlled study aimed to investigate the effect of auriculotherapy on the intensity of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) symptoms.

Ninety-one women were randomly assigned to

- Auriculotherapy (AG),

- Placebo (PG),

- Control (CG) groups.

The intervention was 8 weeks long, done once per week. At each session in AG the microneedles were placed in seven points related to PMS symptoms (Anxiety; Endocrine; Muscle relaxation; Analgesia; Kidney; Shen Men; and Sympathetic). At PG the microneedles also were placed in seven points but unrelated to PMS symptoms (Tonsils; Vocal cords; Teeth; Eyes; Allergy; Mouth; and External nose). The women allocate in the CG received o intervention during the evaluation period.

Assessments of PMS symptoms (Premenstrual Syndrome Screening Tool), musculoskeletal pain (Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire), anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory), and quality of life (WHOQOL-Bref) were done at baseline, before the 5th session, after program completion, and a month follow-up.

The AG and PG showed significantly lower scores of PMS symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, and anxiety. On the quality of life and follow-up analysis, the significance was observed only in PG.

The authors concluded that auriculotherapy can be used as adjunctive therapy to reduce the physical and mood PMS symptoms.

If I understand it correctly (the paper is unclear), verum and placebo were both better than no intervention but showed no significant differences when compared to each other. This is strong evidence that auriculotherapy is, in fact, a placebo. To make matters worse, in the follow-up analysis placebo seems to be superior to auriculotherapy.

Another issue might be adverse effects. Microneedle implants can cause severe complications. Thus it is mandatory to monitor adverse effects in clinical trials. This does not seem to have happened in this case.

The mind boggles!

How on earth could the authors conclude that auriculotherapy can be used as adjunctive therapy to reduce the physical and mood PMS symptoms.

The answer: a case of scientific misconduct?

Cupping is a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) that has been around for millennia in many cultures. We have discussed it repeatedly on this blog (see, for instance, here, here, and here). This new study tested the effects of dry cupping on pain intensity, physical function, functional mobility, trunk range of motion, perceived overall effect, quality of life, psychological symptoms, and medication use in individuals with chronic non-specific low back pain.

Ninety participants with chronic non-specific low back pain were randomized. The experimental group (n = 45) received dry cupping therapy, with cups bilaterally positioned parallel to the L1 to L5 vertebrae. The control group (n = 45) received sham cupping therapy. The interventions were applied once a week for 8 weeks.

Participants were assessed before and after the first treatment session, and after 4 and 8 weeks of intervention. The primary outcome was pain intensity, measured with the numerical pain scale at rest, during fast walking, and during trunk flexion. Secondary outcomes were physical function, functional mobility, trunk range of motion, perceived overall effect, quality of life, psychological symptoms, and medication use.

On a 0-to-10 scale, the between-group difference in pain severity at rest was negligible: MD 0.0 (95% CI -0.9 to 1.0) immediately after the first treatment, 0.4 (95% CI -0.5 to 1.5) at 4 weeks and 0.6 (95% CI -0.4 to 1.6) at 8 weeks. Similar negligible effects were observed on pain severity during fast walking or trunk flexion. Negligible effects were also found on physical function, functional mobility, and perceived overall effect, where mean estimates and their confidence intervals all excluded worthwhile effects. No worthwhile benefits could be confirmed for any of the remaining secondary outcomes.

The authors concluded that dry cupping therapy was not superior to sham cupping for improving pain, physical function, mobility, quality of life, psychological symptoms or medication use in people with non-specific chronic low back pain.

These results will not surprise many of us; they certainly don’t baffle me. What I found interesting in this paper was the concept of sham cupping therapy. How did they do it? Here is their explanation:

For the experimental group, a manual suction pump and four acrylic cups size one (internal diameter = 4.5 cm) were used for the interventions. The cups were applied to the lower back, parallel to L1 to L5 vertebrae, with a 3-cm distance between them, bilaterally. The dry cupping application consisted of a negative pressure of 300 millibars (two suctions in the manual suction pump) sustained for 10 minutes once a week for 8 weeks.

In the control group, the exact same procedures were used except that the cups were prepared with small holes < 2 mm in diameter to release the negative pressure in approximately 3 seconds. Double-sided adhesive tape was applied to the border of the cups in order to keep them in contact with the participants’ skin.

So, sham-controlled trials of cupping are doable. Future trialists might now consider the inclusion of testing the success of patient-blinding when conducting trials of cupping therapy.

Bloodletting therapy (BLT) has been widely used for centuries until it was discovered that it is not merely useless for almost all diseases but also potentially harmful. Yet in so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) BLT is still sometimes employed, for instance, to relieve acute gouty arthritis (AGA). This systematic review aimed to evaluate the feasibility and safety of BLT in treating AGA.

Seven databases were searched from the date of establishment to July 31, 2020, irrespective of the publication source and language. BLT included fire needle, syringe, three-edged needle, and bloodletting followed by cupping. The included articles were evaluated for bias risk by using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool.

Twelve studies involving 894 participants were included in the final analysis. A meta-analysis suggested that BLT was highly effective in relieving pain (MD = -1.13, 95% CI [-1.60, -0.66], P < 0.00001), with marked alterations in the total effective (RR = 1.09, 95% [1.05, 1.14], P < 0.0001) and curative rates (RR = 1.37, 95%CI [1.17, 1.59], P < 0.0001). In addition, BLT could dramatically reduce serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level (MD = -3.64, 95%CI [-6.72, -0.55], P = 0.02). Both BLT and Western medicine (WM) produced comparable decreases in uric acid (MD = -18.72, 95%CI [-38.24, 0.81], P = 0.06) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels (MD = -3.01, 95%CI [-6.89, 0.86], P = 0.13). Lastly, we demonstrated that BLT was safer than WM in treating AGA (RR = 0.36, 95%CI [0.13, 0.97], P = 0.04).

The authors concluded that BLT is effective in alleviating pain and decreasing CRP level in AGA patients with a lower risk of evoking adverse reactions.

This conclusion is optimistic, to say the least. There are several reasons for this statement:

- All the primary studies came from China (and we have often discussed that such trials need to be taken with a pinch of salt).

- All the studies had major methodological flaws.

- There was considerable heterogeneity between the studies.

- The treatments employed were very different from study to study.

- Half of all studies failed to mention adverse effects and thus violate medical ethics.

Aromatherapy, the use of essential oils for medicinal purposes, exists in several guises. One of them is inhalation aromatherapy which is a complementary therapy used in different clinical settings. But is there any sound evidence about its effectiveness?

The aim of this review was to assess the effectiveness of inhalational aromatherapy in the care of hospitalized pediatric patients.

A systematic review of clinical trials and quasi-experimental studies was conducted, based on PRISMA recommendations, searching Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, SciELO, LILACS, CINAHL, Science Direct, EBSCO, and updated databases. The Down and Black 2020, RoB 2020 CLARITY, and ROBINS-I 2020 scales were used through the Distiller SR software to verify the studies’ internal validity and risk of bias.

From 446 articles identified, 9 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Seven were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), one pilot RCT, and one non-randomized quasi-experimental trial.

Different outcomes were analyzed, with pain being the most frequently measured variable. None of the 6 studies that evaluated pain showed significant effects with inhalation aromatherapy. Additionally, non-significant effects were found regarding nausea, vomiting, and behavioral/emotional variables.

The authors concluded that the findings are still inconclusive, and more evidence is required from future studies with high methodological quality, blinding, and adequate sample sizes.

Inconclusive?

Really?

Call me a skeptic, but I think the findings show quite clearly that there is no sound evidence to suggest that inhalation aromatherapy might be effective for kids.

The effectiveness of manipulation versus mobilization for the management of spinal conditions, including cervicogenic headache, is conflicting, and a pragmatic approach comparing manipulation to mobilization has not been examined in a patient population with cervicogenic headache.

This study evaluated the effectiveness of manipulation compared to mobilization applied in a pragmatic fashion for patients with cervicogenic headache.

Forty-five (26 females) patients with cervicogenic headache were randomly assigned to receive either pragmatically selected manipulation or mobilization. Outcomes were measured at baseline, the second visit, discharge, and 1-month follow-up. The endpoints of the study included the Neck Disability Index (NDI), Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), the Global Rating of Change (GRC), the Patient Acceptable Symptoms Scale (PASS). The primary outcome measures were the effects of treatment on disability and pain. They were examined with a mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA), with treatment group (manipulation versus mobilization) as the between-subjects variable and time (baseline, 48 hours, discharge, and follow-up) as the within-subjects variable.

The interaction for the mixed model ANOVA was not statistically significant for NDI (p = 0.91), NPRS (p = 0.81), or HIT (p = 0.89). There was no significant difference between groups for the GRC or PASS.

The authors concluded that manipulation has similar effects on disability, pain, GRC, and cervical range of motion as mobilization when applied in a pragmatic fashion for patients with cervicogenic headaches.

Essentially, this study is an equivalence trial comparing one treatment to another. As such it would need a much larger sample size than the 45 patients enrolled by the investigators. If, however, we ignored this major flaw and assumed the results are valid, they would be consistent with both manipulation and mobilization being pure placebos.

I can imagine that many chiropractors find this conclusion unacceptable. Therefore, let me offer an alternative: both approaches were equally effective. Therefore, mobilization, which is associated with far fewer risks, is preferable. This means that patients suffering from cervicogenic headache should see an osteopath who is less likely to use manipulation than a chiropractor.

And again, I can imagine that many chiropractors find this conclusion unacceptable.

It was only when I came across this recent paper that I realized that, apparently, I am THE WORLD CHAMPION in acupuncture reviews. The aim of this paper was to analyze the 100 most-cited systematic reviews or meta-analyses in the field of acupuncture research.

The Web of Science Core Collection was used to retrieve lists of 100 most-cited systematic reviews or meta-analyses in the field of acupuncture research. Two authors screened literature, extracted data, and analyzed the results.

The citation number of the 100 most-cited systematic reviews or meta-analyses varied from 65 to 577; they were published between 1989 and 2018. Fourteen authors published more than 1 study as the corresponding author and 10 authors published more than 1 study as the first author.

In terms of the corresponding authors, Edzard Ernst and Linde Klaus published the most systematic reviews/meta-analyses (n = 7). The USA published most of the systematic reviews or meta-analyses (n = 24), followed by England (n = 23) and China (n = 14). Most institutions with more than 1 study were from England (4/13). The institutions with the largest numbers of most-cited systematic reviews or meta-analyses were the Technical University of Munich in Germany, the University of Maryland School of Medicine in the USA (n = 8), the Universities of Exeter and Plymouth in England (n = 6), and the University of Exeter in England (n = 6). The journal with the largest number of most-cited systematic reviews or meta-analyses was the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (n = 20), followed by Pain (n = 6). The majority of the 100 most-cited reviews are on pain or pain-related conditions. Only 4 of them focus on safety issues, and all of these are by my team.

The authors concluded that the 100 most-cited systematic reviews or meta-analyses in the acupuncture research field are mostly from high impact factor journals and developed countries. It will help researchers follow research hot spots, broaden their research scope, expand their academic horizons, and explore new research ideas, thereby improving the quality of acupuncture research.

The authors show that, both in the list of corresponding as well as first authors, I am in place number one! Not only that, they furthermore reveal that my department is also in place number 1 (as Universities of Exeter and Plymouth in England (n = 6), and the University of Exeter in England (n = 6) both refer to my unit [in the 19 years it existed the Exeter medical school changed affiliation twice]). This is remarkable, particularly because acupuncture was only one of several research foci of my team (the other 3 being herbal medicine, homeopathy, and spinal manipulation), and my department was closed almost 10 years ago.

When I write about acupuncture these days (mostly on this blog), I often get the impression that the true believers in this therapy don’t especially like what I have to say. I, therefore, fear that the concept of me being the WORLD CHAMPION of acupuncture reviews might cause some degree of displeasure to them.

What can I say?

Sorry guys!

Guest post by Emeritus Professor Alastair MacLennan AO, MB ChB, MD, FRCOG, FRANZCOG

The sale and promotion of a therapeutic drug in most countries require rigorous assessment and licencing by that country’s therapeutic regulatory body. However, a new surgical technique can escape such checks and overview unless the technique is subject to local medical ethics review in the context of a research trial. New medical devices in Australia such as carbon dioxide or Er-YAG lasers can be listed on its therapeutic register without critical review of their efficacy and safety. Thermal injury to the postmenopausal vaginal wall in the hope of rejuvenating it has become a lucrative fad for some surgeons outside formal well-conducted clinical trials.

There are many published studies of this technique but the large majority are small, uncontrolled and observational. The few randomised controlled trials using sham controls show a placebo effect and debatable clinical efficacy with limited follow-up of adverse effects. A review of these therapies in July 2020 published by The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence summarised apparent claims for some efficacy in terms of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, sexual function, and incontinence but noted confounding in the study’s designs such as concurrent breast cancer treatments, local oestrogen therapy and lubricants (!). Most studies had very limited follow up for adverse events but elsewhere the literature has reported burns, infection, increased dyspareunia and scarring. There is no physiological mechanism by which burning atrophic vaginal epithelium will magically rejuvenate it.

A recent well-conducted randomised sham-controlled trial with a 12-month follow-up of Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser for the treatment of vaginal symptoms associated with menopause has been published in JAMA by Li et al has shown no efficacy for this treatment(2).

At 12 months, there was no difference in overall symptom severity based on a 0-100 scale (zero equals no symptoms), with a reduction in symptom severity of 17.2 in the treatment group compared with 26.6 in the sham group.

The treatment had no impact on quality of life. “Sexual activity rates and quality of sex were not significantly different between the groups at baseline or 12 months”. The study compared 46 paired vaginal wall biopsies, taken at baseline and six months into treatment, and no significant histological improvement with laser was evident.

“The annual cost of laser treatment to the individual for management of vaginal menopausal symptoms was reported to be AUD$2,733, and because there is no demonstrable difference versus sham treatment, it cannot be considered to be cost-effective.”

Although one could still call for more quality sham-controlled randomised trials in different circumstances there is no justification for touting this therapy commercially. Complications following this therapy outside of ethical trials could become the next medico-legal mine-field.

Vaginal atrophy in the years after menopause is almost universal and is primarily due to oestrogen deficiency. The efficient solution is local vaginal oestrogen or systemic hormone replacement therapy. However, the misreporting of the Women’s Health Initiative and Million Women’s Study has created exaggerated fear of oestrogen therapies and thus a market for alternative and often unproven therapies (3). The way forward is education and tailoring of hormonal therapies to minimise risk and maximise efficacy and quality of life and not to resort to quackery.

References

1. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg697/documents/overview

2. Li FG, Maheux-Lacroix S, Deans R et al. Effect of Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser vs Sham Treatment on Symptom Severity in Women With Postmenopausal Vaginal Symptoms A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1381-1389.

3. MacLennan AH. Evidence-based review of therapies at the menopause. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2009; 7: 112-123.