massage

I recently came across this paper by Prof. Dr. Chad E. Cook, a physical therapist, PhD, a Fellow of the American Physical Therapy Association (FAPTA), and a professor as well as director of clinical research in the Department of Orthopaedics, Department of Population Health Sciences at the Duke Clinical Research Institute at Duke University in North Carolina, USA. The paper is entitled ‘The Demonization of Manual Therapy‘.

Cook introduced the subject by stating: “In medicine, when we do not understand or when we dislike something, we demonize it. Well-known examples throughout history include the initial ridicule of antiseptic handwashing, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (i. e., balloon angioplasty), the relationships between viruses and cancer, the contribution of bacteria in the development of ulcers, and the role of heredity in the development of disease. In each example, naysayers attempted to discredit the use of each of the concepts, despite having no evidence to support their claims. The goal in each of the aforementioned topics: demonize the concept.”

Cook then discussed 8 ‘demonizations’ of manual therapy. Number 7 is entitled “Causes as Much Harm as Help“. Here is this section in full:

By definition, harms include adverse reactions (e. g., side effects of treatments), and other undesirable consequences of health care products and services. Harms can be classified as “none”, minor, moderate, serious and severe [67]. Most interventions have some harms, typically minor, which are defined as a non-life-threatening, temporary harm that may or may not require efforts to assess for a change in a patient’s condition such as monitoring [67].

There are harms associated with a manual therapy intervention, but they are generally benign (minor). Up to 20 –40 % of individuals will report adverse events after the application of manual therapy. The most common adverse events were soreness in muscles, increased pain, stiffness and tiredness [68]. There are rare occasions of several harms associated with manual therapy and these include spinal or neurological problems as well as cervical arterial strokes [9]. It is critical to emphasize how rare these events are; serious adverse event incidence estimates ranged from 1 per 2 million manipulations to 13 per 10,000 patients [69].

Cook then concludes that “manual therapy has been inappropriately demonized over the last decade and has been associated with inaccurate assumptions and false speculations that many clinicians have acquired over the last decade. This paper critically analyzed eight of the most common assumptions that have belabored manual therapy and identified notable errors in seven of the eight. It is my hope that the physiotherapy community will carefully re-evaluate its stance on manual therapy and consider a more evidence-based approach for the betterment of our patients.

REFERENCES

[9] Ernst E. Adverse effects of spinal manipulation: a systematic review. J R Soc Med 2007; 100: 330–338.doi:10.1177/014107680710000716 [68] Paanalahti K, Holm LW, Nordin M et al. Adverse events after manual therapy among patients seeking care for neck and/or back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 77. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-77 [69] Swait G, Finch R. What are the risks of manual treatment of the spine? A scoping review for clinicians. Chiropr Man Therap 2017; 25: 37. doi:10.1186/s12998-017-0168-5

_________________________________

Here are a few things that I find odd or wrong with Cook’s text:

- The term ‘demonizing’ seems to be a poor choice. The historical examples chosen by Cook were not cases of demonization. They were mostly instances where new discoveries did not fit into the thinking of the time and therefore took a long time to get accepted. They also show that sooner or later, sound evidence always prevails. Lastly, they suggest that speeding up this process via the concept of evidence-based medicine is a good idea.

- Cook then introduces the principle of risk/benefit balance by entitling the cited section “Causes as Much Harm as Help“. Oddly, however, he only discusses the risks of manual therapies and omits the benefit side of the equation.

- This omission is all the more puzzling since he quotes my paper (his reference [9]) states that “the effectiveness of spinal manipulation for most indications is less than convincing.5 A risk-benefit evaluation is therefore unlikely to generate positive results: with uncertain effectiveness and finite risks, the balance cannot be positive.”

- In discussing the risks, he seems to assume that all manual therapies are similar. This is clearly not true. Massage therapies have a very low risk, while this cannot be said of spinal manipulations.

- The harms mentioned by Cook seem to be those of spinal manipulation and not those of all types of manual therapy.

- Cook states that “up to 20 –40 % of individuals will report adverse events after the application of manual therapy.” Yet, the reference he uses in support of this statement is a clinical trial that reported an adverse effect rate of 51%.

- Cook then states that “there are rare occasions of several harms associated with manual therapy and these include spinal or neurological problems as well as cervical arterial strokes.” In support, he quotes one of my papers. In it, I emphasize that “the incidence of such events is unknown.” Cook not only ignores this fact but states in the following sentence that “it is critical to emphasize how rare these events are…”

Cook concludes that “manual therapy has been inappropriately demonized over the last decade and has been associated with inaccurate assumptions and false speculations …” He confuses, I think, demonization with critical assessment.

Cook’s defence of manual therapy is clumsy, inaccurate, ill-conceived, misleading and often borders on the ridiculous. In the age of evidence-based medicine, therapies are not ‘demonized’ but evaluated on the basis of their effectiveness and safety. Manual therapies are too diverse to do this wholesale. They range from various massage techniques, some of which have a positive risk/benefit balance, to high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts, for which the risks do not demonstrably outweigh the benefits.

Myofascial release (also known as myofascial therapy or myofascial trigger point therapy) is a type of low-load stretch therapy that is said to release tightness and pain throughout the body caused by the myofascial pain syndrome, a chronic muscle pain that is worse in certain areas known as trigger points. Various types of health professionals provide myofascial release, e.g. osteopaths, chiropractors, physical or occupational therapists, massage therapists, or sports medicine/injury specialists. The treatment is usually applied repeatedly, but there is also a belief that a single session of myofascial release is effective. This study was a crossover clinical trial aimed to test whether a single session of a specific myofascial release technique reduces pain and disability in subjects with chronic low back pain (CLBP).

A total of 41 participants were randomly enrolled into 3 situations in a balanced and crossover manner:

- experimental,

- placebo,

- control.

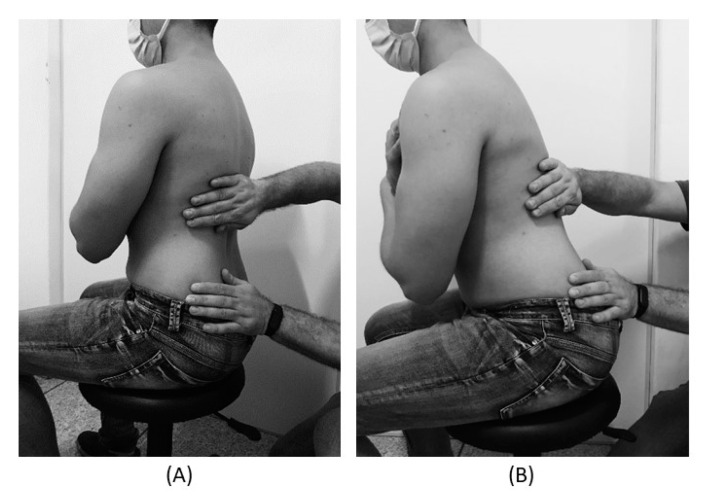

The subjects underwent a single session of myofascial release on thoracolumbar fascia and the results were compared with the control and placebo groups. A single trained and experienced therapist applied the technique.

For the control treatment, the subjects were instructed to remain in the supine position for 5 minutes. For the muscle release session, the subjects were in a sitting position with feet supported and the thoracolumbar region properly undressed. The trunk flexion goniometry of each participant was performed and the value of 30° was marked with a barrier to limit the necessary movement during the technique. The trained researcher positioned their hands on all participants without sliding over the skin or forcing the tissue, with the cranial hand close to the last rib and at the T12–L1 level on the right side of the individual’s body and the caudal hand on the ipsilateral side between the iliac crest and the sacrum. Then, the researcher caused slight traction in the tissues by moving their hands away from each other in a longitudinal direction. Then, the participant was instructed to perform five repetitions of active trunk flexion-extension (30°), while the researcher followed the movement with both hands simultaneously positioned, without losing the initial tissue traction and position. The same technique and the same number of repetitions of active trunk flexion-extension were repeated with the researcher’s hands positioned on the opposite sides. This technique lasted approximately five minutes.

For the placebo treatment, the subjects were not submitted to the technique of manual thoracolumbar fascia release, but they slowly performed ten repetitions of active trunk flexion-extension (30°) in the same position as the experimental situation. Due to the fact that touch can provide not only well-recognized discriminative input to the brain, but also an affective input, there was no touch from the researcher at this stage.

The outcomes, pain, and functionality, were evaluated using the numerical pain rating scale (NPRS), pressure pain threshold (PPT), and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

The results showed no effects between-tests, within-tests, nor for interaction of all the outcomes, i.e., NPRS (η 2 = 0.32, F = 0.48, p = 0.61), PPT (η2 = 0.73, F = 2.80, p = 0.06), ODI (η2 = 0.02, F = 0.02, p = 0.97).

The authors concluded that a single trial of a thoracolumbar myofascial release technique was not enough to reduce pain intensity and disability in subjects with CLBP.

Surprised?

I’m not!

This study describes the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) among older adults who report being hampered in daily activities due to musculoskeletal pain. Cross-sectional European Social Survey (EES) Round 7 (2014) data from 21 countries were examined for participants aged 55 years and older, who reported musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities in the past 12months. From a total of 35,063 individuals who took part in the ESS study, 13,016 (37%) were aged 55 or older; of which 8183 (63%) reported the presence of pain, with a further 4950 (38%) reporting that this pain hampered their daily activities in any way.

Of the 4950 older adult participants reporting musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities, the majority (63.5%) were from the West of Europe, reported secondary education or less (78.2%), and reported at least one other health-related problem (74.6%). In total, 1657 (33.5%) reported using at least one SCAM treatment in the previous year. Manual body-based therapies (MBBTs) were most used, including massage therapy (17.9%) and osteopathy (7.0%). Alternative medicinal systems (AMSs) were also popular with 6.5% using homeopathy and 5.3% reporting herbal treatments. A general trend of higher SCAM use in younger participants was noted.

SCAM usage was associated with

- physiotherapy use,

- female gender,

- higher levels of education,

- being in employment,

- living in West Europe

- having multiple health problems.

The authors concluded that a third of older Europeans with musculoskeletal pain report SCAM use in the previous

12 months. Certain subgroups with higher rates of SCAM use could be identified. Clinicians should comprehensively and routinely assess SCAM use among older adults with musculoskeletal pain.

Such studies have the advantage of large sample sizes, and therefore one is inclined to consider their findings to be reliable and informative. Yet, they resemble big fishing operations where all sorts of important and unimportant stuff is caught in the net. When studying such papers, it is wise to remember that associations do not necessarily reveal causal relationships!

Having said this, I find very little information in these already outdated results (they originate from 2014!) that I would not have expected. Perhaps the most interesting aspect is the nature of the most popular SCAMs used for musculoskeletal problems. The relatively high usage of MBBTs had to be expected; in most of the surveyed countries, massage therapy is considered to be not SCAM but mainstream. The fact that 6.5% used homeopathy to ease their musculoskeletal pain is, however, quite remarkable. I know of no good evidence to show that homeopathy is effective for such problems (in case some homeopathy fans disagree, please show me the evidence).

In my view, this indicates that, in 2014, much needed to be done in terms of informing the public about homeopathy. Many consumers mistook homeopathy for herbal medicine (which btw may well have some potential for musculoskeletal pain), and many consumers had been misguided into believing that homeopathy works. They had little inkling that homeopathy is pure placebo therapy. This means they mistreated their conditions, continued to suffer needlessly, and caused an unnecessary financial burden to themselves and/or to society.

Since 2014, much has happened (as discussed in uncounted posts on this blog), and I would therefore assume that the 6.5% figure has come down significantly … but, as you know:

I am an optimist.

I believe in progress.

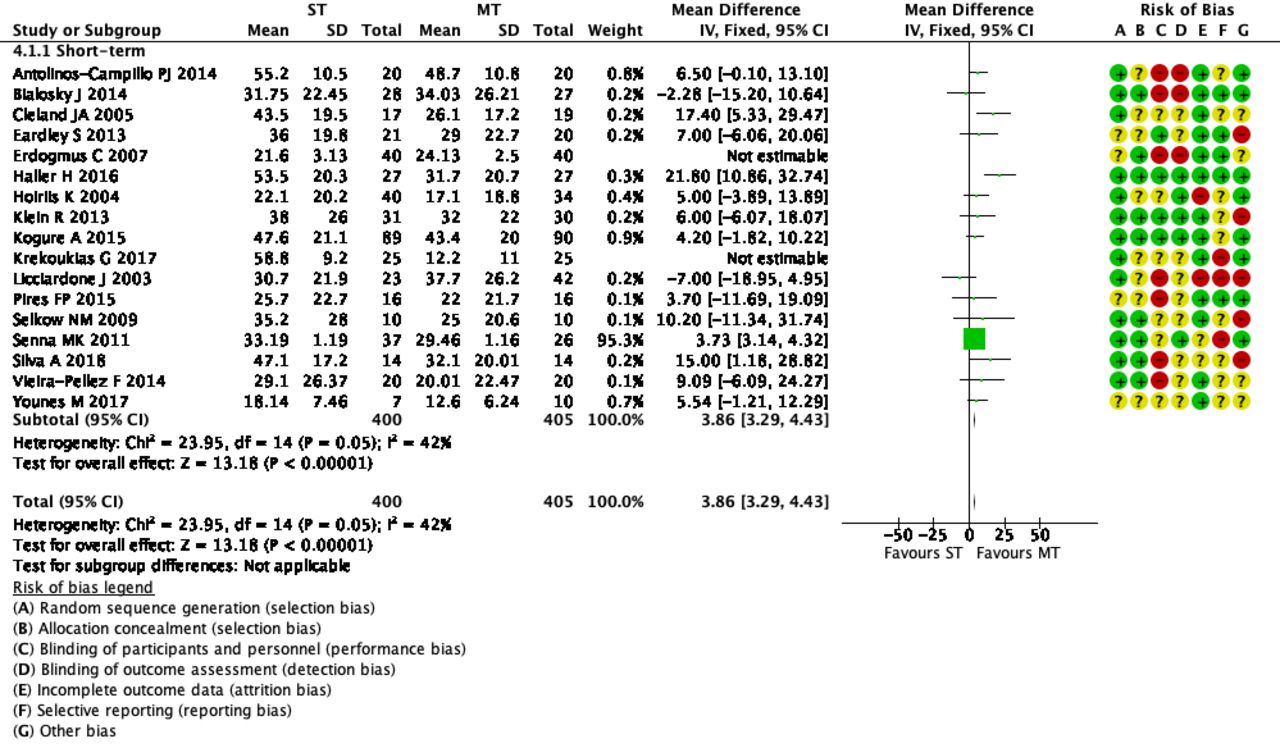

This systematic review assessed the effects and reliability of sham procedures in manual therapy (MT) trials in the treatment of back pain (BP) in order to provide methodological guidance for clinical trial development.

Different databases were screened up to 20 August 2020. Randomized controlled trials involving adults affected by BP (cervical and lumbar), acute or chronic, were included. Hand contact sham treatment (ST) was compared with different MT (physiotherapy, chiropractic, osteopathy, massage, kinesiology, and reflexology) and to no treatment. Primary outcomes were BP improvement, the success of blinding, and adverse effects (AE). Secondary outcomes were the number of drop-outs. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using risk ratio (RR), continuous using mean difference (MD), 95% CIs. The minimal clinically important difference was 30 mm changes in pain score.

A total of 24 trials were included involving 2019 participants. Most of the trials were of chiropractic manipulation. Very low evidence quality suggests clinically insignificant pain improvement in favor of MT compared with ST (MD 3.86, 95% CI 3.29 to 4.43) and no differences between ST and no treatment (MD -5.84, 95% CI -20.46 to 8.78).ST reliability shows a high percentage of correct detection by participants (ranged from 46.7% to 83.5%), spinal manipulation is the most recognized technique. Low quality of evidence suggests that AE and drop-out rates were similar between ST and MT (RR AE=0.84, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.28, RR drop-outs=0.98, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.25). A similar drop-out rate was reported for no treatment (RR=0.82, 95% 0.43 to 1.55).

The authors concluded that MT does not seem to have clinically relevant effect compared with ST. Similar effects were found with no treatment. The heterogeneousness of sham MT studies and the very low quality of evidence render uncertain these review findings. Future trials should develop reliable kinds of ST, similar to active treatment, to ensure participant blinding and to guarantee a proper sample size for the reliable detection of clinically meaningful treatment effects.

The authors concluded that MT does not seem to have clinically relevant effect compared with ST. Similar effects were found with no treatment. The heterogeneousness of sham MT studies and the very low quality of evidence render uncertain these review findings. Future trials should develop reliable kinds of ST, similar to active treatment, to ensure participant blinding and to guarantee a proper sample size for the reliable detection of clinically meaningful treatment effects.

The optimal therapy for back pain does not exist or has not yet been identified; there are dozens of different approaches but none has been found to be truly and dramatically effective. Manual therapies like chiropractic and osteopathy are often used, and some data suggest that they are as good (or as bad) as most other options. This review confirms what we have discussed many times previously (e.g. here), namely that the small positive effect of MT, or specifically spinal manipulation, is largely due to placebo.

Considering this information, what is the best treatment for back pain sufferers? The answer seems obvious: it is a therapy that is as (in)effective as all the others but causes the least harm or expense. In other words, it is not chiropractic nor osteopathy but exercise.

My conclusion:

avoid therapists who use spinal manipulation for back pain.

Tuina is a massage therapy that originates from Traditional Chinese Medicine. Many of the techniques used in tuina resemble those of a western massage like gliding, kneading, vibration, tapping, friction, pulling, rolling, pressing, and shaking. Tuina involves a range of manipulations usually performed by the therapist’s finger, hand, elbow, knee, or foot. They are applied to muscle or soft tissue at specific locations of the body.

The aim of Tuina is to enhance the flow of the ‘vital energy’ or ‘chi’, that is alleged to control our health. Proponents of the therapy recommend Tuina for a range of conditions, including paediatric ones. Paediatric Tuina has been widely used in children with acute diarrhea in China. However, due to a lack of high-quality clinical evidence, the benefit of Tuina is not clear.

This study aimed to assess the effect of paediatric Tuina compared with sham Tuina as add-on therapy in addition to usual care for 0-6-year-old children with acute diarrhea.

Eighty-six participants aged 0-6 years with acute diarrhea were randomized to receive Tuina plus usual care (n = 43) or sham Tuina plus usual care (n = 43). The primary outcomes were days of diarrhea from baseline and times of diarrhea on day 3. Secondary outcomes included a global change rating (GCR) and the number of days when the stool characteristics returned to normal. Adverse events were assessed.

Tuina treatment in the intervention group was performed on the surface of the children’s body using moderate pressure (Fig. 1a). Tuina treatment in the control group was different: the therapist used one hand to hold the child’s hand or put one hand on the child’s body, while the other hand performed manipulations on the therapist’s own hand instead of the child’s hand or body (Fig. (Fig.11b).

Tuina was associated with a reduction in times of diarrhea on day 3 compared with sham Tuina in both ITT and per-protocol analyses. However, the results were not significant when adjusted for social-demographic and clinical characteristics. No significant difference was found between groups in days of diarrhea, global change rating, or number of days when the stool characteristics returned to normal.

The authors concluded that in children aged 0-6 years with acute diarrhea, pediatric Tuina showed significant effects in terms of reducing times of diarrhea compared with sham Tuina. Studies with larger sample sizes and adjusted trial designs are warranted to further evaluate the effect of pediatric Tuina therapy.

This study was well-reported and has interesting features, such as the attempt to use a placebo control and blinding (whether blinding was successful is a different matter and was not tested in the trial). It is, therefore, all the more surprising that the essentially negative result is turned into a positive one. After adjustment, the differences disappear (a fact which the authors hardly mention in the paper), which means they are not due to the treatment but to group differences and confounding. This, in turn, means that the study shows not the effectiveness but the ineffectiveness of Tuina.

Many experts doubt that acupuncture generates the many positive health effects that are being claimed by enthusiasts. Yet, few consider that acupuncture might not be merely useless but could even make things worse. Here is a trial that seems to suggest exactly that.

This study evaluated whether combining two so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs), acupuncture and massage, reduce postoperative stress, pain, anxiety, muscle tension, and fatigue more than massage alone.

Patients undergoing autologous tissue breast reconstruction were randomly assigned to one of two postoperative SCAMs for three consecutive days. All participants were observed for up to 3 months. Forty-two participants were recruited from January 29, 2016 to July 11, 2018. Twenty-one participants were randomly assigned to massage alone and 21 to massage and acupuncture. Stress, anxiety, relaxation, nausea, fatigue, pain, and mood (score 0-10) were measured at enrollment before surgery and postoperative days 1, 2, and 3 before and after the intervention. Patient satisfaction was evaluated.

Stress decreased from baseline for both Massage-Only Group and Massage+Acupuncture Group after each treatment intervention. Change in stress score from baseline decreased significantly more in the Massage-Only Group at pretreatment and posttreatment. After adjustment for baseline values, change in fatigue, anxiety, relaxation, nausea, pain, and mood scores did not differ between groups. When patients were asked whether they would recommend the study, 100% (19/19) of Massage-Only Group and 94% (17/18) of Massage+Acupuncture Group responded yes.

The authors concluded tha no additive beneficial effects were observed with addition of acupuncture to massage for pain, anxiety, relaxation, nausea, fatigue, and mood. Combined massage and acupuncture was not as effective in reducing stress as massage alone, although both groups had significant stress reduction. These findings indicate a need for larger studies to explore these therapies further.

I recently went to the supermarket to find out whether combining two bank notes (£10 + £5) can buy more goods than one £10 note alone. What I found was interesting: the former did indeed purchase more than the latter. Because I am a scientist, I did not stop there; I went to a total of 10 shops and my initial finding was confirmed each time: A+B results in more than A alone.

It stands to reason that the same thing happens with clinical trials. We even tested this hypothesis in a systematic review entitled ‘A trial design that generates only ”positive” results‘. Here is our abstract:

In this article, we test the hypothesis that randomized clinical trials of acupuncture for pain with certain design features (A + B versus B) are likely to generate false positive results. Based on electronic searches in six databases, 13 studies were found that met our inclusion criteria. They all suggested that acupuncture is effective (one only showing a positive trend, all others had significant results). We conclude that the ‘A + B versus B’ design is prone to false positive results and discuss the design features that might prevent or exacerbate this problem.

But why is this not so with the above-mentioned study?

Why is, in this instance, A even more that A+B?

There are, of course, several possible answers. To use my supermarket example again, the most obvious one is that B is not a £5 note but a negative amount, a dept note, in other words: A + B can only be less than A alone, if B is a minus number. In the context of the clinical trail, this means acupuncture must have caused a negative effect.

But is that possible? Evidently yes! Many patients don’t like needles and experience stress at the idea of a therapist sticking one into their body. Thus acupuncture would cause stress, and stress would have a negative effect on all the other parameters quantified in the study (pain, anxiety, muscle tension, and fatigue).

My conclusion: in certain situations, acupuncture is more than just useless; it makes things worse.

The aim of this RCT was to examine symptom responses resulting from a home-based reflexology intervention delivered by a friend/family caregiver to women with advanced breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy, targeted, and/or hormonal therapy.

Patient-caregiver dyads (N = 256) were randomized to 4 weekly reflexology sessions or attention control. Caregivers in the intervention group were trained by a reflexology practitioner in a 30-min protocol. During the 4 weeks, both groups completed telephone symptom assessments using the M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Those who completed at least one weekly call were included in this secondary analysis (N = 209). Each symptom was categorized as mild, moderate, or severe using established interference-based cut-points. Symptom response meant an improvement by at least one category or remaining mild. Symptom responses were treated as multiple events within patients and analysed using generalized estimating equations technique.

Reflexology was more successful than attention control in producing responses for pain with no significant differences for other symptoms. In the reflexology group, greater probability of response across all symptoms was associated with lower number of comorbid condition and lower depressive symptomatology at baseline. Compared to odds of responses on pain (chosen as a referent symptom), greater odds of symptom response were found for disturbed sleep and difficulty remembering with older aged participants.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of symptom responses for reflexology arm versus control (adjusted for age, number of comorbid conditions, depressive symptoms at baseline, and treatment type: chemotherapy with or without hormonal therapy versus hormonal therapy alone)

Symptom OR (95% CI) p value

Fatigue 1.76 (0.99, 3.12) 0.06

Pain 1.84 (1.05, 3.23) 0.03

Disturbed sleep 1.45 (0.76, 2.77) 0.26

Shortness of breath 0.58 (0.26, 1.30) 0.19

Remembering 0.96 (0.51, 1.78) 0.89

Lack of appetite 1.05 (0.45, 2.49) 0.91

Dry mouth 1.84 (0.86, 3.94) 0.12

Numbness and tingling 1.40 (0.75, 2.64) 0.29

Depression 1.38 (0.78, 2.43) 0.27

The authors concluded that home-based caregiver-delivered reflexology was helpful in decreasing patient-reported pain. Age, comorbid conditions, and depression are potentially important tailoring factors for future research and can be used to identify patients who may benefit from reflexology.

This is certainly one of the more rigorous studies of reflexology. It is well designed and reported. How valid are its findings? To a large degree, this seems to depend on the somewhat unusual statistical approach the investigators employed:

Baseline characteristics were summarized by study group for outcome values and potential covariates. The unit of analysis was patient symptom; multiple symptoms were treated as nested within the patient being analyzed, using methodology described by Given et al. [24] and Sikorskii et al. [17]. Patient symptom responses were treated as multiple events, and associations among responses to multiple symptoms within patients were accounted for by specifying the exchangeable correlation structure in the generalized estimating equations (GEE) model. The GEE model was fitted using the GENMOD procedure in SAS 9.4 [25]. A dummy symptom variable with 9 levels was included in the interaction with the trial arm to differentiate potentially different effects of reflexology on different symptoms. Patient-level covariates included age, number of comorbid conditions, type of treatment (chemotherapy or targeted therapy with or without

hormonal therapy versus hormonal therapy only), and the CES-D score at baseline. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained for the essential parameter of study group for each symptom.

Another concern is the fact that the study crucially depended on the reliability of the 256 carers. It is conceivable, even likely, I think, that many carers from both groups were less than strict in adhering to the prescribed protocol. This might have distorted the results in either direction.

Finally, the study was unable to control for the possibly substantial placebo response that a reflexology massage unquestionably provokes. Therefore, we are not able to tell whether the observed effect is due to the agreeable, non-specific effects of touch and foot massages, or to the postulated specific effects of reflexology.

This recent Cochrane review assessed the effects of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for post-caesarean pain. Randomised clinical trials (RCTs), including quasi-RCTs and cluster-RCTs, comparing SCAM, alone or associated with other forms of pain relief, versus other treatments or placebo or no treatment, for the treatment of post-CS pain were included.

A total of 37 studies (3076 women) investigating 8 different SCAM therapies for post-CS pain relief were found. There was substantial heterogeneity among the trials. The primary outcome measures were pain and adverse effects. Secondary outcome measures included vital signs, rescue analgesic requirement at 6 weeks after discharge; all of which were poorly reported or not reported at all.

Acupuncture/acupressure

The quality of the RCTs was low. Whether acupuncture or acupressure (versus no treatment) or acupuncture or acupressure plus analgesia (versus placebo plus analgesia) have any effect on pain. Acupuncture or acupressure plus analgesia (versus analgesia) may reduce pain at 12 hours (standardised mean difference (SMD) -0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) -0.64 to 0.07; 130 women; 2 studies; low-certainty evidence) and 24 hours (SMD -0.63, 95% CI -0.99 to -0.26; 2 studies; 130 women; low-certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether acupuncture or acupressure (versus no treatment) or acupuncture or acupressure plus analgesia (versus analgesia) have any effect on the risk of adverse effects.

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy plus analgesia may reduce pain when compared with placebo plus analgesia at 12 hours (mean difference (MD) -2.63 visual analogue scale (VAS), 95% CI -3.48 to -1.77; 3 studies; 360 women; low-certainty evidence) and 24 hours (MD -3.38 VAS, 95% CI -3.85 to -2.91; 1 study; 200 women; low-certainty evidence). The authors were uncertain whether aromatherapy plus analgesia has any effect on adverse effects (anxiety) compared with placebo plus analgesia.

Electromagnetic therapy

Electromagnetic therapy may reduce pain compared with placebo plus analgesia at 12 hours (MD -8.00, 95% CI -11.65 to -4.35; 1 study; 72 women; low-certainty evidence) and 24 hours (MD -13.00 VAS, 95% CI -17.13 to -8.87; 1 study; 72 women; low-certainty evidence).

Massage

There were 6 RCTs (651 women), 5 of which were quasi-RCTs, comparing massage (foot and hand) plus analgesia versus analgesia. All the evidence relating to pain, adverse effects (anxiety), vital signs and rescue analgesic requirement was very low-certainty.

Music therapy

Music therapy plus analgesia may reduce pain when compared with placebo plus analgesia at one hour (SMD -0.84, 95% CI -1.23 to -0.46; participants = 115; studies = 2; I2 = 0%; low-certainty evidence), 24 hours (MD -1.79, 95% CI -2.67 to -0.91; 1 study; 38 women; low-certainty evidence), and also when compared with analgesia at one hour (MD -2.11, 95% CI -3.11 to -1.10; 1 study; 38 women; low-certainty evidence) and at 24 hours (MD -2.69, 95% CI -3.67 to -1.70; 1 study; 38 women; low-certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether music therapy plus analgesia has any effect on adverse effects (anxiety), when compared with placebo plus analgesia because the quality of evidence is very low.

Reiki

The investigators were uncertain whether Reiki plus analgesia compared with analgesia alone has any effect on pain, adverse effects, vital signs or rescue analgesic requirement because the quality of evidence is very low (one study, 90 women). Relaxation Relaxation may reduce pain compared with standard care at 24 hours (MD -0.53 VAS, 95% CI -1.05 to -0.01; 1 study; 60 women; low-certainty evidence).

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

TENS (versus no treatment) may reduce pain at one hour (MD -2.26, 95% CI -3.35 to -1.17; 1 study; 40 women; low-certainty evidence). TENS plus analgesia (versus placebo plus analgesia) may reduce pain compared with placebo plus analgesia at one hour (SMD -1.10 VAS, 95% CI -1.37 to -0.82; 3 studies; 238 women; low-certainty evidence) and at 24 hours (MD -0.70 VAS, 95% CI -0.87 to -0.53; 108 women; 1 study; low-certainty evidence). TENS plus analgesia (versus placebo plus analgesia) may reduce heart rate (MD -7.00 bpm, 95% CI -7.63 to -6.37; 108 women; 1 study; low-certainty evidence) and respiratory rate (MD -1.10 brpm, 95% CI -1.26 to -0.94; 108 women; 1 study; low-certainty evidence). The authors were uncertain whether TENS plus analgesia (versus analgesia) has any effect on pain at six hours or 24 hours, or vital signs because the quality of evidence is very low (two studies, 92 women).

The authors concluded that some SCAM therapies may help reduce post-CS pain for up to 24 hours. The evidence on adverse events is too uncertain to make any judgements on safety and we have no evidence about the longer-term effects on pain. Since pain control is the most relevant outcome for post-CS women and their clinicians, it is important that future studies of SCAM for post-CS pain measure pain as a primary outcome, preferably as the proportion of participants with at least moderate (30%) or substantial (50%) pain relief. Measuring pain as a dichotomous variable would improve the certainty of evidence and it is easy to understand for non-specialists. Future trials also need to be large enough to detect effects on clinical outcomes; measure other important outcomes as listed in this review, and use validated scales.

I feel that the Cochrane Collaboration does itself no favours by publishing such poor reviews. This one is both poorly conceived and badly reported. In fact, I see little reason to deal with pain after CS differently than with post-operative pain in general. Some of the modalities discussed are not truly SCAM. Most of the secondary endpoints are irrelevant. The inclusion of adverse effects as a primary endpoint seems nonsensical considering that SCAM studies are notoriously bad at reporting them. Many of the allegedly positive findings rely on trial designs that cannot control for placebo effects (e.g A+B versus B); therefore they tell us nothing about the effectiveness of the therapy.

Most importantly, the conclusions are not helpful. I would have simply stated that none of the SCAM modalities are supported by convincing evidence as treatments for pain control after CS.

This Cochrane review assessed the efficacy and safety of aromatherapy for people with dementia. The researchers included randomised controlled trials which compared fragrance from plants in an intervention defined as aromatherapy for people with dementia with placebo aromatherapy or with treatment as usual. All doses, frequencies and fragrances of aromatherapy were considered. Participants in the included studies had a diagnosis of dementia of any subtype and severity.

The investigators included 13 studies with 708 participants. All participants had dementia and in the 12 trials which described the setting, all were resident in institutional care facilities. Nine trials recruited participants because they had significant agitation or other behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD) at baseline. The fragrances used were:

- lavender (eight studies);

- lemon balm (four studies);

- lavender and lemon balm,

- lavender and orange,

- cedar extracts (one study each).

For six trials, assessment of risk of bias and extraction of results was hampered by poor reporting. Four of the other seven trials were at low risk of bias in all domains, but all were small (range 18 to 186 participants; median 66). The primary outcomes were:

- agitation,

- overall behavioural,

- psychological symptoms,

- adverse effects.

Ten trials assessed agitation using various scales. Among the 5 trials for which the confidence in the results was moderate or low, 4 trials reported no significant effect on agitation and one trial reported a significant benefit of aromatherapy. The other 5 trials either reported no useable data or the confidence in the results was very low. Eight trials assessed overall BPSD using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and there was moderate or low confidence in the results of 5 of them. Of these, 4 reported significant benefit from aromatherapy and one reported no significant effect.

Adverse events were poorly reported or not reported at all in most trials. No more than two trials assessed each of our secondary outcomes of quality of life, mood, sleep, activities of daily living, caregiver burden. There was no evidence of benefit on these outcomes. Three trials assessed cognition: one did not report any data and the other two trials reported no significant effect of aromatherapy on cognition. The confidence in the results of these studies was low.

The authors reached the following conclusions: We have not found any convincing evidence that aromatherapy (or exposure to fragrant plant oils) is beneficial for people with dementia although there are many limitations to the data. Conduct or reporting problems in half of the included studies meant that they could not contribute to the conclusions. Results from the other studies were inconsistent. Harms were very poorly reported in the included studies. In order for clear conclusions to be drawn, better design and reporting and consistency of outcome measurement in future trials would be needed.

This is a thorough review. It makes many of the points that I so often make regarding SCAM research:

- too many of the primary studies are badly designed;

- too many of the primary studies are too small;

- too many of the primary studies are poorly reported;

- too many of the primary studies fail to mention adverse effects thus violating research ethics;

- too many of the primary studies are done by pseudo-scientists who use research for promotion rather than testing hypotheses.

It is time that SCAM researchers, ethic review boards, funders, editors and journal reviewers take these points into serious consideration – if only to avoid clinical research getting a bad reputation and losing the support of patients without which it cannot exist.

My new book has just been published. Allow me to try and whet your appetite by showing you the book’s introduction:

“There is no alternative medicine. There is only scientifically proven, evidence-based medicine supported by solid data or unproven medicine, for which scientific evidence is lacking.” These words of Fontanarosa and Lundberg were published 22 years ago.[1] Today, they are as relevant as ever, particularly to the type of healthcare I often call ‘so-called alternative medicine’ (SCAM)[2], and they certainly are relevant to chiropractic.

“There is no alternative medicine. There is only scientifically proven, evidence-based medicine supported by solid data or unproven medicine, for which scientific evidence is lacking.” These words of Fontanarosa and Lundberg were published 22 years ago.[1] Today, they are as relevant as ever, particularly to the type of healthcare I often call ‘so-called alternative medicine’ (SCAM)[2], and they certainly are relevant to chiropractic.

Invented more than 120 years ago by the magnetic healer DD Palmer, chiropractic has had a colourful history. It has now grown into one of the most popular of all SCAMs. Its general acceptance might give the impression that chiropractic, the art of adjusting by hand all subluxations of the three hundred articulations of the human skeletal frame[3], is solidly based on evidence. It is therefore easy to forget that a plethora of fundamental questions about chiropractic remain unanswered.

I wrote this book because I feel that the amount of misinformation on chiropractic is scandalous and demands a critical evaluation of the evidence. The book deals with many questions that consumers often ask:

- How well-established is chiropractic?

- What treatments do chiropractors use?

- What conditions do they treat?

- What claims do they make?

- Are their assumptions reasonable?

- Are chiropractic spinal manipulations effective?

- Are these manipulations safe?

- Do chiropractors behave professionally and ethically?

Am I up to this task, and can you trust my assessments? These are justified questions; let me try to answer them by giving you a brief summary of my professional background.

I grew up in Germany where SCAM is hugely popular. I studied medicine and, as a young doctor, was enthusiastic about SCAM. After several years in basic research, I returned to clinical medicine, became professor of rehabilitation medicine first in Hanover, Germany, and then in Vienna, Austria. In 1993, I was appointed as Chair in Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter. In this capacity, I built up a multidisciplinary team of scientists conducting research into all sorts of SCAM with one focus on chiropractic. I retired in 2012 and am now an emeritus professor. I have published many peer-reviewed articles on the subject, and I have no conflicts of interest. If my long career has taught me anything, it is this: in the best interest of consumers and patients, we must insist on sound evidence; not opinion, not wishful thinking; evidence.

In critically assessing the issues related to chiropractic, I am guided by the most reliable and up-to-date scientific evidence. The conclusions I reach often suggest that chiropractic is not what it is often cracked up to be. Hundreds of books have been published that disagree. If you are in doubt who to trust, the promoter or the critic of chiropractic, I suggest you ask yourself a simple question: who is more likely to provide impartial information, the chiropractor who makes a living by his trade, or the academic who has researched the subject for the last 30 years?

This book offers an easy to understand, concise and dependable evaluation of chiropractic. It enables you to make up your own mind. I want you to take therapeutic decisions that are reasonable and based on solid evidence. My book should empower you to do just that.

[1] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9820267

[2] https://www.amazon.co.uk/SCAM-So-Called-Alternative-Medicine-Societas/dp/1845409701/ref=pd_rhf_dp_p_img_2?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=449PJJDXNTY60Y418S5J

[3] https://www.amazon.co.uk/Text-Book-Philosophy-Chiropractic-Chiropractors-Adjuster/dp/1635617243/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=DD+Palmer&qid=1581002156&sr=8-1