massage

Millions of US adults use so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). In 2012, 55 million adults spent $28.3 billion on SCAMs, comparable to 9% of total out-of-pocket health care expenditures. A recent analysis conducted by the US National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) suggests a substantial increase in the overall use of SCAM by American adults from 2002 to 2022. The paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, highlights a surge in the use of SCAM particularly for pain management.

Data from the 2002, 2012, and 2022 National Health Interview Surveys (NHISs) were employed to evaluate changes in the use of 7 SCAMs:

- yoga,

- meditation,

- massage therapy,

- chiropractic,

- acupuncture,

- naturopathy,

- guided imagery/progressive muscle relaxation.

The key findings include:

- The percentage of individuals who reported using at least one of the SCAMs increased from 19.2% in 2002 to 36.7% in 2022.

- The use of yoga, meditation, and massage therapy experienced the most significant growth.

- Use of yoga increased from 5% in 2002 to 16% in 2022.

- Meditation became the most popular SCAM in 2022, with an increase from 7.5% in 2002 to 17.3% in 2022.

- Acupuncture saw an increase from 1% in 2002 to 2.2% in 2022.

- The smallest rise was noted for chiropractic, from 79 to 86%

The analyses also suggested a rise in the proportion of US adults using SCAMs specifically for pain management. Among participants using any SCAM, the percentage reporting use for pain management increased from 42% in 2002 to 49% in 2022.

Limitations of the survey include:

- decreasing NHIS response rates over time,

- possible recall bias,

- cross-sectional data,

- differences in the wording of the surveys.

The NCCIH researchers like such surveys and tend to put a positive spin on them, i.e. SCAM is becoming more and more popular because it is supported by better and better evidence. Therefore, SCAM should be available to everyone who wants is.

But, of course, the spin could also turn in the opposite direction, i.e. the risk/benefit balance for most SCAMs is either negative or uncertain, and their cost-benefit remains unclear – as seen regularly on this blog. Therefore, the fact that SCAM seems to be getting more popular is of increasing concern. In particular, more consideration ought to be given to the indirect risks of SCAM (think, for instance, only of the influence SCAM practitioners have on the vaccination rates) that we often discuss here but that the NCCIH conveniently tends to ignore.

We have often asked whether the General Chiropractic Council (GCC) is fit for purpose. A recent case bought before the Professional Conduct Committee (PCC) of the GCC provides further food for thought.

The male chiropractor in question admitted to the PCC that:

- he had requested the younger female patient remove her clothing to her underwear for the purposes of examination;

- he then treated the area near her vagina and groin with a vibrating tool;

- that he also treated the area around her breasts.

After the appointment, which the patient had originally booked for a problem with her neck, the patient reflected on the treatment and eventually complained about the chiropractor to the GCC. The PCC considered the case and did not find unprofessional conduct in the actions and conduct of the chiropractor. His the diagnosis and treatment were both found to be clinically justified.

According to the GCC, the lesson from this case is that the complaint to the GCC may have been avoided if the chiropractor had been more alert to the need to ensure he communicated effectively so that the patient was clear as to why the intimate areas were being treated and, on that basis, given informed consent. Patients often feel vulnerable before, during and after treatment; and this effect is magnified when the patient is unclothed, new to chiropractic treatment or the work of a particular chiropractor, or they are being treated in an intimate area. Chiropractors can reduce this feeling of vulnerability by offering a chaperone and gown (and recording a note of the patient’s response) as well as taking the time to ensure you have fully explained the procedure to them and obtained informed consent. Standard D4 of the GCC Code states registrants must “Consider the need, during assessments and care, for another person to be present to act as a chaperone; particularly if the assessment or care might be considered intimate or where the patient is a child or a vulnerable adult.”

Excuse me?

I find this unbelievably gross and grossly unbelievable!

It begs, I think, the following questions:

- What condition requires treatment with a ‘vibrating tool’ near the vagina (I assume they mean vulva)?

- What condition requires treatment with a ‘vibrating tool’ around the breasts?

- Is there any reliable evidence?

- Was informed consent obtained?

- What precisely did it entail?

About 15 years ago, I was an expert witness in a very similar UK case. The defendant was sent to prison for two years. The GCC is really not fit for purpose. It seems to consistently defend chiropractors rather than do its duty and defend their patients.

My advice to the above-mentioned patient is not to bother with the evidently useless GCC but to initiale criminal proceedings.

Supportive care is often assumed to be beneficial in managing the anxiety symptoms common in patients in sterile hematology unit. The authors of this study hypothesize that personal massage can help the patient, particularly in this isolated setting where physical contact is extremely limited.

The main objective of this study therefore was to show that anxiety could be reduced after a touch-massage performed by a nurse trained in this therapy.

A single-center, randomized, unblinded controlled study in the sterile hematology unit of a French university hospital, validated by an ethics committee. The patients, aged between 18 and 65 years old, and suffering from a serious and progressive hematological pathology, were hospitalized in sterile hematology unit for a minimum of three weeks. They were randomized into either a group receiving 15-minute touch-massage sessions or a control group receiving an equivalent amount of quiet time once a week for three weeks.

In the treated group, anxiety was assessed before and after each touch-massage session, using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory questionnaire with subscale state (STAI-State). In the control group, anxiety was assessed before and after a 15-minute quiet period. For each patient, the difference in the STAI-State score before and after each session (or period) was calculated, the primary endpoint was based on the average of these three differences. Each patient completed the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire before the first session and after the last session.

Sixty-two patients were randomized. Touch-massage significantly decreased patient anxiety: a mean decrease in STAI-State scale score of 10.6 [7.65-13.54] was obtained for the massage group (p ≤ 0.001) compared with the control group. The improvement in self-esteem score was not significant.

The authors concluded that this study provides convincing evidence for integrating touch-massage in the treatment of patients in sterile hematology unit.

I find this conclusion almost touching (pun intended). The wishful thinking of the amateur researchers is almost palpable.

Yes, I mean AMATEUR, despite the fact that, embarrassingly, the authors are affiliated with prestigeous institutions:

- 1Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, Service Interdisciplinaire Douleur, Soins Palliatifs et de Support, Médecine intégrative, UIC 22, Nantes, F-44000, France.

- 2Université Paris Est, EA4391 Therapeutic and Nervous Excitability, Creteil, F-93000, France.

- 3Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, Hematology Department, Nantes, F-44000, France.

- 4Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, CRCI2NA – INSERM UMR1307, CNRS UMR 6075, Equipe 12, Nantes, F-44000, France.

- 5Institut Curie, Paris, France.

- 6Université Paris Versailles Saint-Quentin, Versailles, France.

- 7Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, Direction de la Recherche et l’Innovation, Coordination Générale des Soins, Nantes, F-44000, France.

- 8Methodology and Biostatistics Unit, DRCI CHU Nantes CHD Vendée, La Roche Sur Yon, F-85000, France.

- 9Nantes Université, CHU Nantes, Service Interdisciplinaire Douleur, Soins Palliatifs et de Support, Médecine intégrative, UIC 22, Nantes, F-44000, France. [email protected].

So, why do I feel that they must be amateurs?

- Because, if they were not amateurs, they would know that a clinical trial should not aim to show something, but to test something.

- Also, if they were not amateurs, they would know that perhaps the touch-massage itself had nothing to do with the outcome, but that the attention, sympathy and empathy of a therapist or a placebo effect can generate the observed effect.

- Lastly, if they were not amateurs, they would not speak of convincing evidence based on a single, small, and flawed study.

Jean-Maurice Latsague (85 years old) has a track record of sexual assaults. Recently, he stood trial before the Sarthe Assize Court from 13 to 15 December for rapes committed during healing sessions. He has worked as an energy healer for many years, and it was in this capacity that he came into conflict with the law nearly 30 years ago.

- In 1994, he was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment for the rape and indecent assault of minors that he had committed in the Dordogne.

- In February 2023, he settled in Sarthe after his release from prison and was again convicted for sexual assaults.

- Now we’re talking about crimes again, with an accusation of rape against two women.

During the first few hours of the current trial, Jean-Maurice Latsague listened to the proceedings, bent over on his cane. He explained that he had asked his patients to strip naked because “healing energy doesn’t pass through tissue”.

The healing sessions seemed to always follow the same routine:

- They begin with discussions.

- This is followed by prayers.

- Subsequently, Jean-Maurice Latsague asks his victims to strip naked.

- Then he administeres massages with oil.

- Finally, he rapes his victim.

On the second day of the proceedings, one of the victims chose to bring a civil action. She is one of three other women attacked by Jean-Maurice Latsague (apart from a mother and daughter who gave evidence before), but who had not lodged a complaint at the time of the investigation.

New testimony sheds light on the healer’s practices, in a much more sordid and perverse way. “He would masturbate in front of me to stimulate ovulation,” said a victim who took the witness stand and was undergoing treatment for infertility.

At the end of a three-day trial, the Sarthe Assize Court found Jean-Maurice Latsague guilty of repeated rape and sexual assault committed by a person abusing the authority conferred by his position.

He was sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment.

Sources:

Un magnétiseur accusé de plusieurs viols devant les Assises de la Sarthe (francetvinfo.fr)

À 85 ans, le magnétiseur condamné à vingt ans de réclusion criminelle pour viols (ouest-france.fr)

Manual therapy is considered a safe and less painful method and has been increasingly used to alleviate chronic neck pain. However, there is controversy about the effectiveness of manipulation therapy on chronic neck pain. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed to determine the effectiveness of manipulative therapy for chronic neck pain.

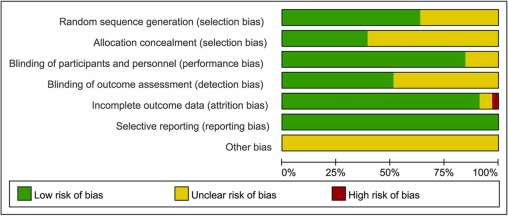

A search of the literature was conducted on seven databases (PubMed, Cochrane Center Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, Medline, CNKI, WanFang, and SinoMed) from the establishment of the databases to May 2022. The review included RCTs on chronic neck pain managed with manipulative therapy compared with sham, exercise, and other physical therapies. The retrieved records were independently reviewed by two researchers. Further, the methodological quality was evaluated using the PEDro scale. All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan V.5.3 software. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) assessment was used to evaluate the quality of the study results.

Seventeen RCTs, including 1190 participants, were included in this meta-analysis. Manipulative therapy showed better results regarding pain intensity and neck disability than the control group. Manipulative therapy was shown to relieve pain intensity (SMD = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] = [-1.04 to -0.62]; p < 0.0001) and neck disability (MD = -3.65; 95% CI = [-5.67 to – 1.62]; p = 0.004). However, the studies had high heterogeneity, which could be explained by the type and control interventions. In addition, there were no significant differences in adverse events between the intervention and the control groups.

The authors concluded that manipulative therapy reduces the degree of chronic neck pain and neck disabilities.

Only a few days ago, we discussed another systematic review that drew quite a different conclusion: there was very low certainty evidence supporting cervical SMT as an intervention to reduce pain and improve disability in people with neck pain.

How can this be?

Systematic reviews are supposed to generate reliable evidence!

How can we explain the contradiction?

There are several differences between the two papers:

- One was published in a SCAM journal and the other one in a mainstream medical journal.

- One was authored by Chinese researchers, the other one by an international team.

- One included 17, the other one 23 RCTs.

- One assessed ‘manual/manipulative therapies’, the other one spinal manipulation/mobilization.

The most profound difference is that the review by the Chinese authors is mostly on Chimese massage [tuina], while the other paper is on chiropractic or osteopathic spinal manipulation/mobilization. A look at the Chinese authors’ affiliation is revealing:

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China.

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- Department of Tuina and Spinal Diseases Research, The Third School of Clinical Medicine (School of Rehabilitation Medicine), Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China; Department of Tuina, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

What lesson can we learn from this confusion?

Perhaps that Tuina is effective for neck pain?

No!

What the abstract does not tell us is that the Tuina studies are of such poor quality that the conclusions drawn by the Chinese authors are not justified.

What we do learn – yet again – is that

- Chinese papers need to be taken with a large pintch of salt. In the present case, the searches underpinning the review and the evaluations of the included primary studies were clearly poorly conducted.

- Rubbish journals publish rubbish papers. How could the reviewers and the editors have missed the many flaws of this paper? The answer seems to be that they did not care. SCAM journals tend to publish any nonsense as long as the conclusion is positive.

Massage is frequently used for recovery and increased performance. This review, aimed to search and systemize current literature findings relating to massages’ effects on sports and exercise performance concerning its effects on motor abilities and neurophysiological and psychological mechanisms.

One hundred and fourteen articles were included. The data revealed that massages, in general, do not affect motor abilities, except flexibility. However, several studies demonstrated that positive muscle force and strength changed 48 h after the massage was given. Concerning neurophysiological parameters, massage did not change blood lactate clearance, muscle blood flow, muscle temperature, or activation. However, many studies indicated a reduction of pain and delayed onset muscle soreness, which are probably correlated with the reduction of the level of creatine kinase enzyme and psychological mechanisms. In addition, massage treatment led to a decrease in depression, stress, anxiety, and the perception of fatigue and an increase in mood, relaxation, and the perception of recovery.

The authors concluded that the direct usage of massages just for gaining results in sport and exercise performance seems questionable. However, it is indirectly connected to performance as an important tool when an athlete should stay focused and relaxed during competition or training and recover after them.

The evidence about the value of massage therapy is limited through the mostly poor quality of the primary studies. Unfortunately, the review authors did not bother to address this issue. Another recent and in my opinion more rigorous review identified 29 eligible studies recruiting 1012 participants, representing the largest examination of the effects of massage. Its authors found no evidence that massage improves measures of strength, jump, sprint, endurance, or fatigue, but massage was associated with small but statistically significant improvements in flexibility and DOMS. Massage therapy has the additional advantage that it is agreeable and nearly free of adverse effects. So, on balance, I think massage therapy might be worth considering for athletes.

Massages are experienced as agreeable by most patients. But that does not necessarily mean that it improves our quality of life. This study tests whether it does.

This study compared three massage dosing strategies among inpatients receiving palliative care consultation. It was designed as a three-armed randomized trial examining three different doses of therapist-applied massage to test change in overall quality of life (QoL) and symptoms among hospitalized adult patients receiving palliative care consultation for any indication:

- Arm I: 10-min massage daily × 3 days;

- Arm II: 20-min massage daily × 3 days;

- Arm III: single 20-min massage.

The primary outcome measure was the single-item McGill QoL question. Secondary outcomes measured pain/symptoms, rating of peacefulness, and satisfaction with the intervention. Data were collected at baseline, pre-and post-treatment, and one-day post-last treatment (follow-up). Repeated measure analysis of variance and paired t-test were used to determine significant differences.

A total of 387 patients participated (55.7 (±15.49) years old, mostly women (61.2%) and African-American (65.6%)). All three arms demonstrated within-group improvement at follow-up for McGill QoL (all P < 0.05). No significant between-group differences were found. Finally, repeated measure analyses demonstrated time to predict immediate improvement in distress (P ≤ 0.003) and pain (P ≤ 0.02) for all study arms; however, only improvement in distress was sustained at follow-up measurement in arms with three consecutive daily massages of 10 or 20 minutes.

The authors concluded that massage therapy in complex patients with advanced illness was beneficial beyond dosage. Findings support session length (10 or 20 minutes) was predictive of short-term improvements while treatment frequency (once or three consecutive days) predicted sustained improvement at follow-up.

I like this study because it teaches us an important lesson:

IF ONE DESIGNS A SILLY STUDY, ONE IS LIKELY TO ARRIVE AT A SILLY CONCLUSION.

This study does not have a proper control group. Therefore, we cannot know whether the observed outcomes were due to the different interventions or to non-specific effects such as expectation, the passing of time, etc.

The devil’s advocate conclusion of the findings is thus dramatically different from that of the authors: the results of this trial are consistent with the notion that massage has no effect on QoL, no matter how it is dosed.

This meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was aimed at evaluating the effects of massage therapy in the treatment of postoperative pain.

Three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) were searched for RCTs published from database inception through January 26, 2021. The primary outcome was pain relief. The quality of RCTs was appraised with the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool. The random-effect model was used to calculate the effect sizes and standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidential intervals (CIs) as a summary effect. The heterogeneity test was conducted through I2. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were used to explore the source of heterogeneity. Possible publication bias was assessed using visual inspection of funnel plot asymmetry.

The analysis included 33 RCTs and showed that MT is effective in reducing postoperative pain (SMD, -1.32; 95% CI, −2.01 to −0.63; p = 0.0002; I2 = 98.67%). A similarly positive effect was found for both short (immediate assessment) and long terms (assessment performed 4 to 6 weeks after the MT). Neither the duration per session nor the dose had a significant impact on the effect of MT, and there was no difference in the effects of different MT types. In addition, MT seemed to be more effective for adults. Furthermore, MT had better analgesic effects on cesarean section and heart surgery than orthopedic surgery.

The authors concluded that MT may be effective for postoperative pain relief. We also found a high level of heterogeneity among existing studies, most of which were compromised in the methodological quality. Thus, more high-quality RCTs with a low risk of bias, longer follow-up, and a sufficient sample size are needed to demonstrate the true usefulness of MT.

The authors discuss that publication bias might be possible due to the exclusion of all studies not published in English. Additionally, the included RCTs were extremely heterogeneous. None of the included studies was double-blind (which is, of course, not easy to do for MT). There was evidence of publication bias in the included data. In addition, there is no uniform evaluation standard for the operation level of massage practitioners, which may lead to research implementation bias.

Patients who have just had an operation and are in pain are usually thankful for the attention provided by carers. It might thus not matter whether it is provided by a massage or other therapist. The question is: does it matter? For the patient, it probably doesn’t; However, for making progress, it does, in my view.

In the end, we have to realize that, with clinical trials of certain treatments, scientific rigor can reach its limits. It is not possible to conduct double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of MT. Thus we can only conclude that, for some indications, massage seems to be helpful (and almost free of adverse effects).

This is also the conclusion that has been drawn long ago in some countries. In Germany, for instance, where I trained and practiced in my younger years, Swedish massage therapy has always been an accepted, conventional form of treatment (while exotic or alternative versions of massage therapy had no place in routine care). And in Vienna where I was chair of rehab medicine I employed about 8 massage therapists in my department.

When I conduct my regular literature searches, I am invariably delighted to find a paper that shows the effectiveness of a so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Contrary to the impression that I might give to some, I like positive results as much as the next person. So, today you find me pleased to yet again report about one of my favorite SCAMs.

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) in breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) patients.

In total, 11 RCTs involving 1564 patients could be included, and 10 trials were deemed viable for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Due to the effects of MLD for BCRL, statistically significant improvements were found on the incidence of lymphedema (RR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.37, 0.93], P =.02) and pain intensity (SMD = -0.72, 95% CI [-1.34, -0.09], P = .02). Besides, the meta-analysis carried out implied that the effects that MLD had on volumetric changes of lymphedema and quality of life, were not statistically significant.

The authors concluded that the current evidence based on the RCTs shows that pain of BCRL patients undergoing MLD is significantly improved, while our findings do not support the use of MLD in improving volumetric of lymphedema and quality of life. Note that the effect of MLD for preventing BCRL is worthy of discussion.

Lymph drainage is so well-established in cancer care that most people would probably consider it a conventional treatment. If, however, you read for which conditions its inventor, Emil Vodder, used to promote it, they might change their minds. Vodder saw it as a cure for most illnesses, even those for which there is no plausibility or good evidence.

As far as I can see, lymph drainage works well for reducing lymph edema but, for all other conditions, it is not evidence-based. And this is the reason why I still categorize it as a SCAM.

This study described osteopathic practise activity, scope of practice and the osteopathic patient profile in order to understand the role osteopathy plays within the United Kingdom’s (UK) health system a decade after the authors’ previous survey.

The researchers used a retrospective questionnaire survey design to ask about osteopathic practice and audit patient case notes. All UK-registered osteopaths were invited to participate in the survey. The survey was conducted using a web-based system. Each participating osteopath was asked about themselves, and their practice and asked to randomly select and extract data from up to 8 random new patient health records during 2018. All patient-related data were anonymized.

The survey response rate was 500 osteopaths (9.4% of the profession) who provided information about 395 patients and 2,215 consultations. Most osteopaths were:

- self-employed (81.1%; 344/424 responses),

- working alone either exclusively or often (63.9%; 237/371),

- able to offer 48.6% of patients an appointment within 3 days (184/379).

Patient ages ranged from 1 month to 96 years (mean 44.7 years, Std Dev. 21.5), of these 58.4% (227/389) were female. Infants <1 years old represented 4.8% (18/379) of patients. The majority of patients presented with musculoskeletal complaints (81.0%; 306/378) followed by pediatric conditions (5%). Persistent complaints (present for more than 12 weeks before the appointment) were the most common (67.9%; 256/377) and 41.7% (156/374) of patients had co-existing medical conditions.

The most common treatment approaches used at the first appointment were:

- soft-tissue techniques (73.9%; 292/395),

- articulatory techniques (69.4%; 274/395),

- high-velocity low-amplitude thrust (34.4%; 136/395),

- cranial techniques (23%).

The mean number of treatments per patient was 7 (mode 4). Osteopaths’ referral to other healthcare practitioners amounted to:

- GPs 29%

- Other complementary therapists 21%

- Other osteopaths 18%

The authors concluded that osteopaths predominantly provide care of musculoskeletal conditions, typically in private practice. To better understand the role of osteopathy in UK health service delivery, the profession needs to do more research with patients in order to understand their needs and their expected outcomes of care, and for this to inform osteopathic practice and education.

What can we conclude from a survey that has a 9% response rate?

Nothing!

If I ignore this fact, do I find anything of interest here?

Not a lot!

Perhaps just three points:

- Osteopaths use high-velocity low-amplitude thrusts, the type of manipulation that has most frequently been associated with serious complications, too frequently.

- They also employ cranial osteopathy, which is probably the least plausible technique in their repertoire, too often.

- They refer patients too frequently to other SCAM practitioners and too rarely to GPs.

To come back to the question asked in the title of this post: What do UK osteopaths do? My answer is

ALMOST NOTHING THAT MIGHT BE USEFUL.