herbal medicine

This systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials were performed to summarize the evidence of the effects of Urtica dioica (UD) consumption on metabolic profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Eligible studies were retrieved from searches of PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases until December 2019. Cochran (Q) and I-square statistics were used to examine heterogeneity across included clinical trials. Data were pooled using a fixed-effect or random-effects model and expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

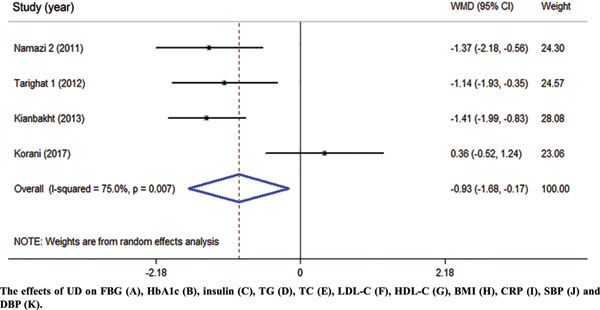

Among 1485 citations, thirteen clinical trials were found to be eligible for the current metaanalysis. UD consumption significantly decreased levels of fasting blood glucose (FBG) (WMD = – 17.17 mg/dl, 95% CI: -26.60, -7.73, I2 = 93.2%), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (WMD = -0.93, 95% CI: – 1.66, -0.17, I2 = 75.0%), C-reactive protein (CRP) (WMD = -1.09 mg/dl, 95% CI: -1.64, -0.53, I2 = 0.0%), triglycerides (WMD = -26.94 mg/dl, 95 % CI = [-52.07, -1.82], P = 0.03, I2 = 90.0%), systolic blood pressure (SBP) (WMD = -5.03 mmHg, 95% CI = -8.15, -1.91, I2 = 0.0%) in comparison to the control groups. UD consumption did not significantly change serum levels of insulin (WMD = 1.07 μU/ml, 95% CI: -1.59, 3.73, I2 = 63.5%), total-cholesterol (WMD = -6.39 mg/dl, 95% CI: -13.84, 1.05, I2 = 0.0%), LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) (WMD = -1.30 mg/dl, 95% CI: -9.95, 7.35, I2 = 66.1%), HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) (WMD = 6.95 mg/dl, 95% CI: -0.14, 14.03, I2 = 95.4%), body max index (BMI) (WMD = -0.16 kg/m2, 95% CI: -1.77, 1.44, I2 = 0.0%), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (WMD = -1.35 mmHg, 95% CI: -2.86, 0.17, I2= 0.0%) among patients with T2DM.

The authors concluded that UD consumption may result in an improvement in levels of FBS, HbA1c, CRP, triglycerides, and SBP, but did not affect levels of insulin, total-, LDL-, and HDL-cholesterol, BMI, and DBP in patients with T2DM.

Several plants have been reported to affect the parameters of diabetes. Whenever I read such results, I cannot stop wondering whether this is a good or a bad thing. It seems to be positive at first glance, yet I can imagine at least two scenarios where such effects might be detrimental:

- A patient reads about the antidiabetic effects and decides to swap his medication for the herbal remedy which is far less effective. Consequently, the patient’s metabolic control is insufficient.

- A patient adds the herbal remedy to his therapy. Consequently, his blood sugar drops too far and he suffers a hypoglycemic episode.

My advice to diabetics is therefore this: if you want to try herbal antidiabetic treatments, please think twice. And if you persist, do it only under the close supervision of your doctor.

For quite some time now, I have had the impression that the top journals of general medicine show less and less interest in so-called alternative medicine. So, I decided to do some Medline searches to check. Specifically, I searched for 4 different SCAMs:

- homeopathy

- acupuncture

- chiropractic

- herbal medicine

I wanted to see how often 7 leading medical journals from the US, UK, Australia, Germany, and Austria carried articles indexed under these headings:

- JAMA – US

- NEJM – US

- BMJ – UK

- Lancet – UK

- Aust J Med – Australia

- Dtsch Med Wochenschrift – Germany

- Wien Med Wochenschrift – Austria

This is what I found (the 1st number is the total number of articles ever listed; the 2nd number is the maximum number in any year; the 3rd number in brackets is the year when that maximum occurred)

JAMA

Homeopathy: 17, 3 (1998)

Acupuncture: 176, 21 (2017)

Chiropractic: 49, 4 (1998)

Herbal medicine: 43, 5 (2001)

NEJM

Homeopathy: 6, 3 (1986)

Acupuncture: 49, 8 (1974)

Chiropractic: 43, 13 (1980)

Herbal medicine: 29, 12 (1999)

BMJ

Homeopathy: 122, (10, 1995)

Acupuncture: 405, 31 (2021)

Chiropractic: 99, 11 (2021)

Herbal medicine: 158, 13 (2018)

Lancet

Homeopathy: 75, 11 (2005)

Acupuncture: 93, 12 (1973)

Chiropractic: 20, 5 (1993)

Herbal medicine: 46, 6 (1993)

Aust J Med

Homeopathy: 9, 2 (2010)

Acupuncture: 78, 13 (1974)

Chiropractic: 34, 4 (1985)

Herbal medicine: 20, 2 (2017)

Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift

Homeopathy: 27, 4 (1999)

Acupuncture: 34, 6 (1978)

Chiropractic: 14, 3 (1972)

Herbal medicine: 6, 1 (2020)

Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift

Homeopathy: 11, 4 (2005)

Acupuncture: 32, 8 (1998)

Chiropractic: 8, 2 (1956)

Herbal medicine: 16, 3 (2002)

These figures need, of course, to be taken with a rather large pinch of salt. There are many pitfalls in interpreting them, e.g. misclassifications by Medline. Yet they are, I think, revealing in that they suggest several interesting trends.

- All in all, my suspicion that the top journals of various countries are less and less keen on SCAM seems to be confirmed. The years where the maximum of papers on specific SCAMs was published are often long in the past.

- The UK journals seem to be by far more open to SCAM that the publications from other countries. This is mostly due to the BMJ – in fact, it turns out to be the online journal ‘BMJ-open’. And this again is to a great part caused by the BMJ-open carrying a sizable amount of acupuncture papers in recent months.

- The two US journals seem particularly cautious about SCAM papers. When looking at the type of articles in the US journals (and especially the NEJM), one realizes that most of them are ‘letters to the editor’ which seems to confirm the dislike of these journals for publishing original research into SCAM. Another interpretation of this phenomenon, of course, would be that only very few SCAM studies are of a high enough quality to make it into these two top journals.

- I was amazed to see how little SCAM was published in the two German-language journals. Vis a vis the high popularity of SCAM in these countries, I find this not easy to understand. Perhaps, one also needs to consider that these two journals publish considerably less original research than the other publications

- If we look at the differences between the 4 types of SCAM included in my assessment, we find that acupuncture is by far the most frequently published modality. The other 3 are on roughly the same level, with chiropractic being the least frequent – which I thought was surprising.

- Overall, the findings do not generate the impression that – despite the many billions spent on SCAM research during the last decades – SCAM has made important inroads into science or medicine.

I have often commented on the dismal state of the many SCAM journals; these days, they seem to publish almost exclusively poor-quality papers with misleading conclusions. It can therefore be expected that these journals will be more and more discarded by everyone (except the few SCAM advocates who publish their rubbish in them) as some sort of cult publications. In turn, this means that only SCAM studies published in mainstream journals will have the potential of generating any impact at all.

For this reason, my little survey might be relevant. It is far from conclusive, of course, yet it might provide a rough picture of what is happening in the area of SCAM research.

This study describes the use of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) among older adults who report being hampered in daily activities due to musculoskeletal pain. The characteristics of older adults with debilitating musculoskeletal pain who report SCAM use is also examined. For this purpose, the cross-sectional European Social Survey Round 7 from 21 countries was employed. It examined participants aged 55 years and older, who reported musculoskeletal pain that hampered daily activities in the past 12 months.

Of the 4950 older adult participants, the majority (63.5%) were from the West of Europe, reported secondary education or less (78.2%), and reported at least one other health-related problem (74.6%). In total, 1657 (33.5%) reported using at least one SCAM treatment in the previous year.

The most commonly used SCAMs were:

- manual body-based therapies (MBBTs) including massage therapy (17.9%),

- osteopathy (7.0%),

- homeopathy (6.5%)

- herbal treatments (5.3%).

SCAM use was positively associated with:

- younger age,

- physiotherapy use,

- female gender,

- higher levels of education,

- being in employment,

- living in West Europe,

- multiple health problems.

(Many years ago, I have summarized the most consistent determinants of SCAM use with the acronym ‘FAME‘ [female, affluent, middle-aged, educated])

The authors concluded that a third of older Europeans with musculoskeletal pain report SCAM use in the previous 12 months. Certain subgroups with higher rates of SCAM use could be identified. Clinicians should comprehensively and routinely assess SCAM use among older adults with musculoskeletal pain.

I often mutter about the plethora of SCAM surveys that report nothing meaningful. This one is better than most. Yet, much of what it shows has been demonstrated before.

I think what this survey confirms foremost is the fact that the popularity of a particular SCAM and the evidence that it is effective are two factors that are largely unrelated. In my view, this means that more, much more, needs to be done to inform the public responsibly. This would entail making it much clearer:

- which forms of SCAM are effective for which condition or symptom,

- which are not effective,

- which are dangerous,

- and which treatment (SCAM or conventional) has the best risk/benefit balance.

Such information could help prevent unnecessary suffering (the use of ineffective SCAMs must inevitably lead to fewer symptoms being optimally treated) as well as reduce the evidently huge waste of money spent on useless SCAMs.

A press release informs us that the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Government of India recently signed an agreement to establish the ‘WHO Global Centre for Traditional Medicine’. This global knowledge centre for traditional medicine, supported by an investment of USD 250 million from the Government of India, aims to harness the potential of traditional medicine from across the world through modern science and technology to improve the health of people and the planet.

“For many millions of people around the world, traditional medicine is the first port of call to treat many diseases,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “Ensuring all people have access to safe and effective treatment is an essential part of WHO’s mission, and this new center will help to harness the power of science to strengthen the evidence base for traditional medicine. I’m grateful to the Government of India for its support, and we look forward to making it a success.”

The term traditional medicine describes the total sum of the knowledge, skills and practices indigenous and different cultures have used over time to maintain health and prevent, diagnose and treat physical and mental illness. Its reach encompasses ancient practices such as acupuncture, ayurvedic medicine and herbal mixtures as well as modern medicines.

“It is heartening to learn about the signing of the Host Country Agreement for the establishment of Global Centre for Traditional Medicine (GCTM). The agreement between Ministry of Ayush and World Health Organization (WHO) to establish the WHO-GCTM at Jamnagar, Gujarat, is a commendable initiative,” said Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India. “Through various initiatives, our government has been tireless in its endeavour to make preventive and curative healthcare, affordable and accessible to all. May the global centre at Jamnagar help in providing the best healthcare solutions to the world.”

The new WHO centre will concentrate on building a solid evidence base for policies and standards on traditional medicine practices and products and help countries integrate it as appropriate into their health systems and regulate its quality and safety for optimal and sustainable impact.

The new centre focuses on four main strategic areas: evidence and learning; data and analytics; sustainability and equity; and innovation and technology to optimize the contribution of traditional medicine to global health and sustainable development.

The onsite launch of the new WHO global centre for traditional medicine in Jamnagar, Gujarat, India will take place on April 21, 2022.

__________________________

Of course, one must wait and see who will direct the unit and what work the new centre produces. But I cannot help feeling a little anxious. The press release is full of hot air and platitudes and the track record of the Indian Ministry of Ayush is quite frankly abominable. Here are a few of my previous posts that, I think, justify this statement:

- Mucormycosis (black fungus): is the Indian AYUSH ministry trying to decimate the population?

- The ‘AYUSH COVID-19 Helpline’: have they gone bonkers?

- Individualized Homeopathic Medicines for Cutaneous Warts – the dishonesty of homeopaths continues

- Ever wondered what a homeopathic egg on the face looks like?

- An RCT on the efficacy of ayurvedic treatment on asymptomatic COVID-19 patients

- Has homeopathy caused the dramatic decline of COVID-19 cases in India?

- Eight new products aimed at mitigating COVID-19. But do they really work?

- Siddha doctors have joined those claiming to have found a cure for COVID-19

- COVID-19: homeopathy gone berserk in Mumbai

- Brazil and India collaborate in the promotion of quackery

- Hard to believe: dangerous GOVERNMENTAL advice regarding SCAM for the corona virus pandemic

WATCH THIS SPACE!

No 10-year follow-up study of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (LDH) has so far been published. Therefore, the authors of this paper performed a prospective 10-year follow-up study on the integrated treatment of LDH in Korea.

One hundred and fifty patients from the baseline study, who initially met the LDH diagnostic criteria with a chief complaint of radiating pain and received integrated treatment, were recruited for this follow-up study. The 10-year follow-up was conducted from February 2018 to March 2018 on pain, disability, satisfaction, quality of life, and changes in a herniated disc, muscles, and fat through magnetic resonance imaging.

Sixty-five patients were included in this follow-up study. Visual analogue scale score for lower back pain and radiating leg pain were maintained at a significantly lower level than the baseline level. Significant improvements in Oswestry disability index and quality of life were consistently present. MRI confirmed that disc herniation size was reduced over the 10-year follow-up. In total, 95.38% of the patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the treatment outcomes and 89.23% of the patients claimed their condition “improved” or “highly improved” at the 10-year follow-up.

The authors concluded that the reduced pain and improved disability was maintained over 10 years in patients with LDH who were treated with nonsurgical Korean medical treatment 10 years ago. Nonsurgical traditional Korean medical treatment for LDH produced beneficial long-term effects, but future large-scale randomized controlled trials for LDH are needed.

This study and its conclusion beg several questions:

WHAT DID THE SCAM CONSIST OF?

The answer is not provided in the paper; instead, the authors refer to 3 previous articles where they claim to have published the treatment schedule:

The treatment package included herbal medicine, acupuncture, bee venom pharmacopuncture and Chuna therapy (Korean spinal manipulation). Treatment was conducted once a week for 24 weeks, except herbal medication which was taken twice daily for 24 weeks; (1) Acupuncture: frequently used acupoints (BL23, BL24, BL25, BL31, BL32, BL33, BL34, BL40, BL60, GB30, GV3 and GV4)10 ,11 and the site of pain were selected and the needles were left in situ for 20 min. Sterilised disposable needles (stainless steel, 0.30×40 mm, Dong Bang Acupuncture Co., Korea) were used; (2) Chuna therapy12 ,13: Chuna is a Korean spinal manipulation that includes high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts to spinal joints slightly beyond the passive range of motion for spinal mobilisation, and manual force to joints within the passive range; (3) Bee venom pharmacopuncture14: 0.5–1 cc of diluted bee venom solution (saline: bee venom ratio, 1000:1) was injected into 4–5 acupoints around the lumbar spine area to a total amount of 1 cc using disposable injection needles (CPL, 1 cc, 26G×1.5 syringe, Shinchang medical Co., Korea); (4) Herbal medicine was taken twice a day in dry powder (2 g) and water extracted decoction form (120 mL) (Ostericum koreanum, Eucommia ulmoides, Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Achyranthes bidentata, Psoralea corylifolia, Peucedanum japonicum, Cibotium barometz, Lycium chinense, Boschniakia rossica, Cuscuta chinensis and Atractylodes japonica). These herbs were selected from herbs frequently prescribed for LBP (or nerve root pain) treatment in Korean medicine and traditional Chinese medicine,15 and the prescription was further developed through clinical practice at Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine.9 In addition, recent investigations report that compounds of C. barometz inhibit osteoclast formation in vitro16 and A. japonica extracts protect osteoblast cells from oxidative stress.17 E. ulmoides has been reported to have osteoclast inhibitive,18 osteoblast-like cell proliferative and bone mineral density enhancing effects.19 Patients were given instructions by their physician at treatment sessions to remain active and continue with daily activities while not aggravating pre-existing symptoms. Also, ample information about the favourable prognosis and encouragement for non-surgical treatment was given.

The traditional Korean spinal manipulations used (‘Chuna therapy’ – the references provided for it do NOT refer to this specific way of manipulation) seemed interesting, I thought. Here is an explanation from an unrelated paper:

Chuna, which is a traditional manual therapy practiced by Korean medicine doctors, has been applied to various diseases in Korea. Chuna manual therapy (CMT) is a technique that uses the hand, other parts of the doctor’s body or other supplementary devices such as a table to restore the normal function and structure of pathological somatic tissues by mobilization and manipulation. CMT includes various techniques such as thrust, mobilization, distraction of the spine and joints, and soft tissue release. These techniques were developed by combining aspects of Chinese Tuina, chiropratic, and osteopathic medicine.[13] It has been actively growing in Korea, academically and clinically, since the establishment of the Chuna Society (the Korean Society of Chuna Manual Medicine for Spine and Nerves, KSCMM) in 1991.[14] Recently, Chuna has had its effects nationally recognized and was included in the Korean national health insurance in March 2019.[15]

This almost answers the other questions I had. Almost, but not quite. Here are two more:

- The authors conclude that the SCAM produced beneficial long-term effects. But isn’t it much more likely that the outcomes their uncontrolled observations describe are purely or at least mostly a reflection of the natural history of lumbar disc herniation?

- If I remember correctly, I learned a long time ago in medical school that spinal manipulation is contraindicated in lumbar disc herniation. If that is so, the results might have been better, if the patients of this study had not received any SCAM at all. In other words, are the results perhaps due to firstly the natural history of the condition and secondly to the detrimental effects of the SCAM the investigators applied?

If I am correct, this would then be the 4th article reporting the findings of a SCAM intervention that aggravated lumbar disc herniation.

PS

I know that this is a mere hypothesis but it is at least as plausible as the conclusion drawn by the authors.

Ginseng plants belong to the genus Panax and include:

- Panax ginseng (Korean ginseng),

- Panax notoginseng (South China ginseng),

- and Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng).

They are said to have a range of therapeutic activities, some of which could render ginseng a potential therapy for viral or post-viral infections. Ginseng has therefore been used to treat fatigue in various patient groups and conditions. But does it work for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also often called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)? This condition is a complex, little-understood, and often disabling chronic illness for which no curative or definitive therapy has yet been identified.

This systematic review aimed to assess the current state of evidence regarding ginseng for CFS. Multiple databases were searched from inception to October 2020. All data was extracted independently and in duplicates. Outcomes of interest included the effectiveness and safety of ginseng in patients with CFS.

A total of two studies enrolling 68 patients were deemed eligible: one randomized clinical trial and one prospective observational study. The certainty of evidence in the effectiveness outcome was low and moderate in both studies, while the safety evidence was very low as reported from one study.

The authors concluded that the study findings highlight a potential benefit of ginseng therapy in the treatment of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions due to limited clinical studies. The paucity of data warrants limited confidence. There is a need for future rigorous studies to provide further evidence.

To get a feeling of how good or bad the evidence truly is, we must of course look at the primary studies.

The prospective observational study turns out to be a mere survey of patients using all sorts of treatments. It included 155 subjects who provided information on fatigue and treatments at baseline and follow-up. Of these subjects, 87% were female and 79% were middle-aged. The median duration of fatigue was 6.7 years. The percentage of users who found a treatment helpful was greatest for coenzyme Q10 (69% of 13 subjects), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (65% of 17 subjects), and ginseng (56% of 18 subjects). Treatments at 6 months that predicted subsequent fatigue improvement were vitamins (p = .08), vigorous exercise (p = .09), and yoga (p = .002). Magnesium (p = .002) and support groups (p = .06) were strongly associated with fatigue worsening from 6 months to 2 years. Yoga appeared to be most effective for subjects who did not have unclear thinking associated with fatigue.

The second study investigated the effect of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) on chronic fatigue (CF) by various measurements and objective indicators. Participants were randomized to KRG or placebo group (1:1 ratio) and visited the hospital every 2 weeks while taking 3 g KRG or placebo for 6 weeks and followed up 4 weeks after the treatment. The fatigue visual analog score (VAS) declined significantly in each group, but there were no significant differences between the groups. The 2 groups also had no significant differences in the secondary outcome measurements and there were no adverse events. Sub-group analysis indicated that patients with initial fatigue VAS below 80 mm and older than 50 years had significantly greater reductions in the fatigue VAS if they used KRG rather than placebo. The authors concluded that KRG did not show absolute anti-fatigue effect but provided the objective evidence of fatigue-related measurement and the therapeutic potential for middle-aged individuals with moderate fatigue.

I am at a loss in comprehending how the authors of the above-named review could speak of evidence for potential benefit. The evidence from the ‘observational study’ is largely irrelevant for deciding on the effectiveness of ginseng, and the second, more rigorous study fails to show that ginseng has an effect.

So, is ginseng a promising treatment for ME?

I doubt it.

Brite is an herbal energy drink that is currently being marketed aggressively. It is even for sale in one leading UK supermarket. It comes in various flavors the ingredients of which vary slightly.

The pineapple/mango drink, for instance, contains:

- guarana extract,

- green tea extract,

- guayusa extract,

- ashwagandha extract,

- matcha tea,

- ascorbic acid (vitamin C),

- natural caffeine.

The website of the manufacturer tells us that Brite uses ingredients and dosages that are safe and effective, utilising the power of nootropic superfoods organic Matcha, Guarana and Guayusa to provide a long-lasting boost.

Brite is based on peer reviewed, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials and studies that can be found here.

It does not tell us the dosages of the ingredients, and I am puzzled by the claim that the drink is safe. A quick search seems to cast considerable doubt on it.

_____________________________

Guarana (Paullinia cupana) is a plant from the Amazon region with a high content of bioactive compounds. It is by no means free of adverse effects. It is known to interact with:

- armodafinil

- caffeine

- dexmethylphenidate

- dextroamphetamine

- green tea

- lisdexamfetamine

- methamphetamine

- methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- methylphenidate

- modafinil

- phentermine

- yohimbine

And it can cause the following adverse effects:

- Abdominal spasms (from overdose)

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Convulsions

- Delirium

- Dependence

- Diarrhea

- Dizziness

- Fast heart rate

- Gastrointestinal (GI) upset

- Headache

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High blood sugar (hyperglycemia)

- Increased respiration

- Increased urination

- Insomnia

- Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias)

- Irritability

- Muscle spasms

- Nausea/vomiting

- Nervousness

- Painful urination (from overdose)

- Rapid breathing

- Restlessness

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Stomach cramps or irritation

- Tremors

- Withdrawal symptoms

Green tea is made from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant. It can cause the following adverse effects:

- headache,

- nervousness,

- sleep problems,

- vomiting,

- diarrhea,

- irritability,

- irregular heartbeat,

- tremor,

- heartburn,

- dizziness,

- ringing in the ears,

- convulsions,

- confusion.

Guayusa is a plant native to the Amazon rainforest that contains plenty of caffeine. Its adverse effects include:

- High Blood Pressure

- Rapid Heartbeat

- Anxiety

- Jitters

- Energy Crashes

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Upset Stomach

Ashwagandha is a plant from India; the root and berry are used in Ayurvedic medicine. Its adverse effects include:

- stomach upset,

- diarrhea,

- vomiting.

Matcha tea also contains a high amount of caffeine. It is associated with the following adverse effects:

- nervousness,

- irritability,

- dizziness,

- anxiety,

- digestive disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, or diarrhea,

- sleeping disorders,

- cardiac arrhythmia.

Caffeine is a chemical found in coffee, tea, cola, guarana, mate, and other products. Adverse effects include:

- insomnia,

- nervousness,

- restlessness,

- stomach irritation,

- nausea and vomiting,

- increased heart rate and respiration,

- headache,

- anxiety,

- agitation,

- chest pain,

- ringing in the ears.

A case report documented a case of myocardial infarction in a 25-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with chest pain. The patient had been consuming massive quantities of caffeinated energy drinks daily for the past week. This case report and previously documented studies support a possible connection between caffeinated energy drinks and myocardial infarction.

________________________

Yes, the adverse effects are predominantly (but not exclusively) caused by high doses. Yet, the claim that Brite is safe should nevertheless be taken with a very large pinch of salt. If I like the taste of the drink and thus consume a few bottles per day, the dosages of the ingredients would surely be high!

And what about the claim that it is effective? Here the pinch of salt must be even larger, I am afraid. I could not find a single trial that confirmed the notion. For backing up their claims, the manufacturers offer a few references, but if you look them up, you will find that they were not done with the mixture of ingredients contained in Brite.

So, what is the conclusion?

Based on the evidence that I have seen, the herbal drink ‘Brite’ has not been shown to be an effective nootropic. In addition, there are legitimate concerns about the safety of the product. I for one will therefore not purchase the (rather expensive) drink.

The associations between so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and negative attitudes to vaccinations are, as discussed repeatedly on this blog, strong and undeniable. A new paper sheds more light on these issues.

By far the most common strategy used in the attempt to modify negative attitudes toward vaccination is to appeal to evidence-based reasoning. However, focusing on science comprehension is inconsistent with one of the key facts of cognitive psychology: Humans are biased information processors and often engage in motivated reasoning. On this basis, it is hypothesized that negative attitudes can be explained primarily by factors unrelated to the empirical evidence for vaccination; including some shared attitudes that also attract people to SCAM.

This study tested psychosocial factors associated with SCAM endorsement in past research; including aspects of spirituality, intuitive (vs analytic) thinking styles, and the personality trait of openness to experience. These relationships were tested in a cross-sectional, stratified CATI survey (N = 1256, 624 Females).

Questions regarding SCAM were derived from a previously validated instrument, designed to standardize the measurement of SCAM utilization, and distinguish between those that use a particular SCAM from those that do not. Each SCAM item provided an indication of whether the respondent had utilized each of the following therapeutic or self-treatment activities within the last 12 months:

- herbal and homeopathic remedies,

- energy-based and body therapies (including therapeutic massage),

- vitamins, yoga, meditation, prayer, body therapies, hypnosis, spiritual healing,

- and chiropractic or osteopathic treatments.

The results show that educational level and thinking style did not predict vaccination rejection. Psychosocial factors such as

- preferring SCAM to conventional medicine (OR .49, 95% CI .36-.66),

- endorsement of spirituality as a source of knowledge (OR .83, 95% CI .71-.96),

- openness (OR .86, 95% CI .74-.99),

all predicted negative attitudes to vaccination. Furthermore, for 9 of the 12 SCAMs surveyed, utilisation in the last 12 months was associated with lower levels of vaccination endorsement. Additionally, the rank-order correlation between the number of different alternative therapies used in the last 12 months and vaccination attitude score was significant. Finally, analytical thinking style was negatively related to all forms of CAM, with this relationship significant in three cases:

- herbal remedies ρ = −.08, p = .0014,

- homeopathy, ρ = −.06, p = .0236,

- prayer for the purpose of healing, ρ = −.15, p < .0001.

The authors concluded that vaccination scepticism appears to be the outcome of a particular cultural and psychological orientation leading to unwillingness to engage with the scientific evidence. Vaccination compliance might be increased either by building general confidence and understanding of evidence-based medicine, or by appealing to features usually associated with SCAM, e.g. ‘strengthening your natural resistance to disease’.

In the discussion section of their paper, the authors argue that these results describe a vaccine sceptic as viewing themselves as anti-authoritarian and unconventional, with a preference for unorthodox treatments with spiritual or ‘life-affirming’ features. The significant effect for personality, but not for cognitive style, is congruent with the notion that it is a reluctance to engage with the evidence, rather than a lack of capacity to appropriately process the evidence, that predicts vaccination scepticism…

SCAM endorsement and vaccination scepticism are components of a common attitudinal stance, with some shared psychosocial determinants. The results of the present study indicate that vaccination rejection is related to psychosocial factors: a general preference for complementary over conventional medicines, valuing diverse and unconventional alternatives, and a spiritual orientation to attitude formation. The null findings with regard to cognitive style and educational level suggest that factors unrelated to the actual empirical evidence for vaccination – i.e. a particular personality and attitudinal mindset are most instrumental in determining vaccination attitudes. Efforts to counter vaccination concerns should be mindful that negative vaccination views appear to form part of a broader attitudinal system that does not necessarily trust empirical or positivist evidence from authoritative sources. Vaccination promotion efforts may benefit from targeting groups associated with SCAM and building general confidence in scientific medicine, rather than targeting specific misunderstandings regarding vaccination.

Holland & Barrett (H&B), the UK’s largest store for supplements and wellbeing products, is under pressure over its links to oligarch Mikhail Fridman. The private equity firm ‘LetterOne’, founded by Fridman, holds a major stake in H&B. On Twitter, people thus urged us to buy our supplements elsewhere. One customer tweeted: ‘Please boycott Holland & Barrett as it is owned by a Russian oligarch with links to Putin.’

Fridman who owns Athlone House, a sprawling £65million mansion in Highgate, North London, was sanctioned by the European Union. His assets were frozen and he is banned from traveling. Consequently, he spoke out against the fighting in Ukraine but refused to denounce Putin. He has since stepped down from the board of LetterOne.

Holland & Barrett itself is unlikely to face sanctions as the oligarch owns less than half the shares in the parent company LetterOne. Fridman convened a press conference last week, which was broadcast on television. However, the move might have backfired, as it alerted H&B shoppers to his connection with the stores.

Fridman was born in Ukraine and has an Israelian passport. He made most of his £11billion fortune from oil, gas, banking, and telecoms. He founded Alfa Bank in January 1991, which grew to become one of the largest private banks in Russia. In 2013, he set up LetterOne in London using £11billion raised from the sale of his stake in TNKBP to Kremlin-backed oil giant Rosneft, whose petrol is currently fuelling Russian tanks. Fridman and Aven (another oligarch) own just under 50 percent of LetterOne. The rest of the company is split between board members German Khan, Alexey Kuzmichev and Andrei Kosogov – who all left the board recently.

A spokesman for LetterOne said: ‘Holland and Barrett is a fantastic business. The business employs thousands of people and we will do everything to protect them.’ Holland & Barrett’s made a gross profit of £445million for the year to the end of September 2020. Fridman and Aven said the EU sanctions are spurious and unfounded and vowed to contest them.

____________________

PS

Quite apart from the oligarch co-ownership, I did ask myself some time ago: is H&B a recommendable shop? It is advertised on Facebook as follows:

On 27 January 2022, I conducted a very simple Medline search using the search term ‘Chinese Herbal Medicine, Review, 2022’. Its results were remarkable; here are the 30 reviews I found:

- Zhu, S. J., Wang, R. T., Yu, Z. Y., Zheng, R. X., Liang, C. H., Zheng, Y. Y., Fang, M., Han, M., & Liu, J. P. (2022). Chinese herbal medicine for myasthenia gravis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Integrative medicine research, 11(2), 100806.

- Lu, J., Li, W., Gao, T., Wang, S., Fu, C., & Wang, S. (2022). The association study of chemical compositions and their pharmacological effects of Cyperi Rhizoma (Xiangfu), a potential traditional Chinese medicine for treating depression. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 287, 114962.

- Su, F., Sun, Y., Zhu, W., Bai, C., Zhang, W., Luo, Y., Yang, B., Kuang, H., & Wang, Q. (2022). A comprehensive review of research progress on the genus Arisaema: Botany, uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 285, 114798.

- Nanjala, C., Ren, J., Mutie, F. M., Waswa, E. N., Mutinda, E. S., Odago, W. O., Mutungi, M. M., & Hu, G. W. (2022). Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and conservation of the genus Calanthe R. Br. (Orchidaceae). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 285, 114822.

- Li, M., Jiang, H., Hao, Y., Du, K., Du, H., Ma, C., Tu, H., & He, Y. (2022). A systematic review on botany, processing, application, phytochemistry and pharmacological action of Radix Rehmnniae. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 285, 114820.

- Mutinda, E. S., Mkala, E. M., Nanjala, C., Waswa, E. N., Odago, W. O., Kimutai, F., Tian, J., Gichua, M. K., Gituru, R. W., & Hu, G. W. (2022). Traditional medicinal uses, pharmacology, phytochemistry, and distribution of the Genus Fagaropsis (Rutaceae). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 284, 114781.

- Xu, Y., Liu, J., Zeng, Y., Jin, S., Liu, W., Li, Z., Qin, X., & Bai, Y. (2022). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity and quality control of medicinal genus Aralia: A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 284, 114671.

- Peng, Y., Chen, Z., Li, Y., Lu, Q., Li, H., Han, Y., Sun, D., & Li, X. (2022). Combined therapy of Xiaoer Feire Kechuan oral liquid and azithromycin for mycoplasma Pneumoniae pneumonia in children: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 96, 153899.

- Xu, W., Li, B., Xu, M., Yang, T., & Hao, X. (2022). Traditional Chinese medicine for precancerous lesions of gastric cancer: A review. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 146, 112542.

- Wang, Y., Greenhalgh, T., Wardle, J., & Oxford TCM Rapid Review Team (2022). Chinese herbal medicine (“3 medicines and 3 formulations”) for COVID-19: rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 28(1), 13–32.

- Chen, X., Lei, Z., Cao, J., Zhang, W., Wu, R., Cao, F., Guo, Q., & Wang, J. (2022). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and current uses of underutilized Xanthoceras sorbifolium bunge: A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 283, 114747.

- Liu, X., Li, Y., Bai, N., Yu, C., Xiao, Y., Li, C., & Liu, Z. (2022). Updated evidence of Dengzhan Shengmai capsule against ischemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 283, 114675.

- Chen, J., Zhu, Z., Gao, T., Chen, Y., Yang, Q., Fu, C., Zhu, Y., Wang, F., & Liao, W. (2022). Isatidis Radix and Isatidis Folium: A systematic review on ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 283, 114648.

- Tian, J., Shasha, Q., Han, J., Meng, J., & Liang, A. (2022). A review of the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Fructus Gardeniae (Zhi-zi). Journal of ethnopharmacology, 114984. Advance online publication.

- Wong, A. R., Yang, A., Li, M., Hung, A., Gill, H., & Lenon, G. B. (2022). The Effects and Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine on Blood Lipid Profiles in Placebo-Controlled Weight-Loss Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM, 2022, 1368576.

- Lu, C., Ke, L., Li, J., Wu, S., Feng, L., Wang, Y., Mentis, A., Xu, P., Zhao, X., & Yang, K. (2022). Chinese Medicine as an Adjunctive Treatment for Gastric Cancer: Methodological Investigation of meta-Analyses and Evidence Map. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 797753.

- Niu, L., Xiao, L., Zhang, X., Liu, X., Liu, X., Huang, X., & Zhang, M. (2022). Comparative Efficacy of Chinese Herbal Injections for Treating Severe Pneumonia: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 743486.

- Zhang, L., Huang, J., Zhang, D., Lei, X., Ma, Y., Cao, Y., & Chang, J. (2022). Targeting Reactive Oxygen Species in Atherosclerosis via Chinese Herbal Medicines. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2022, 1852330.

- Zhou, X., Guo, Y., Yang, K., Liu, P., & Wang, J. (2022). The signaling pathways of traditional Chinese medicine in promoting diabetic wound healing. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 282, 114662.

- Yang, M., Shen, C., Zhu, S. J., Zhang, Y., Jiang, H. L., Bao, Y. D., Yang, G. Y., & Liu, J. P. (2022). Chinese patent medicine Aidi injection for cancer care: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 282, 114656.

- Liu, H., & Wang, C. (2022). The genus Asarum: A review on phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, toxicology and pharmacokinetics. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 282, 114642.

- Lin, Z., Zheng, J., Chen, M., Chen, J., & Lin, J. (2022). The Efficacy and Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 56 Randomized Controlled Trials. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2022, 6887988.

- Yu, R., Zhang, S., Zhao, D., & Yuan, Z. (2022). A systematic review of outcomes in COVID-19 patients treated with western medicine in combination with traditional Chinese medicine versus western medicine alone. Expert reviews in molecular medicine, 24, e5.

- Mo, X., Guo, D., Jiang, Y., Chen, P., & Huang, L. (2022). Isolation, structures and bioactivities of the polysaccharides from Radix Hedysari: A review. International journal of biological macromolecules, 199, 212–222.

- Yang, L., Chen, X., Li, C., Xu, P., Mao, W., Liang, X., Zuo, Q., Ma, W., Guo, X., & Bao, K. (2022). Real-World Effects of Chinese Herbal Medicine for Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy (REACH-MN): Protocol of a Registry-Based Cohort Study. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12, 760482.

- Zhang, R., Zhang, Q., Zhu, S., Liu, B., Liu, F., & Xu, Y. (2022). Mulberry leaf (Morus alba L.): A review of its potential influences in mechanisms of action on metabolic diseases. Pharmacological research, 175, 106029.

- Yuan, J. Y., Tong, Z. Y., Dong, Y. C., Zhao, J. Y., & Shang, Y. (2022). Research progress on icariin, a traditional Chinese medicine extract, in the treatment of asthma. Allergologia et immunopathologia, 50(1), 9–16.

- Zeng, B., Wei, A., Zhou, Q., Yuan, M., Lei, K., Liu, Y., Song, J., Guo, L., & Ye, Q. (2022). Andrographolide: A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and clinical trials and pharmaceutical researches. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 36(1), 336–364.

- Zhang, L., Xie, Q., & Li, X. (2022). Esculetin: A review of its pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 36(1), 279–298.

- Wang, D. C., Yu, M., Xie, W. X., Huang, L. Y., Wei, J., & Lei, Y. H. (2022). Meta-analysis on the effect of combining Lianhua Qingwen with Western medicine to treat coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of integrative medicine, 20(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2021.10.005

The amount of reviews alone is remarkable, I think: more than one review per day! Apart from their multitude, the reviews are noteworthy for other reasons as well.

- Their vast majority arrived at positive or at least encouraging conclusions.

- Most of the primary studies are from China (and we have often discussed how unreliable these trials are).

- Many of the primary studies are not accessible.

- Those that are accessible tend to be of lamentable quality.

I fear that all this is truly dangerous. The medical literature is being swamped with reviews of Chinese herbal medicine and other TCM modalities. Collectively they give the impression that these treatments are supported by sound evidence. Yet, the exact opposite is the case.

The process that is happening in front of our very eyes is akin to that of money laundering. Unreliable and often fraudulent data is being white-washed and presented to us as evidence.

The result:

WE ARE BEING SYSTEMATICALLY MISLED!