critical thinking

Osteopathy is currently regulated in 12 European countries: Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Switzerland, and the UK. Other countries such as Belgium and Norway have not fully regulated it. In Austria, osteopathy is not recognized or regulated. The Osteopathic Practitioners Estimates and RAtes (OPERA) project was developed as a Europe-based survey, whereby an updated profile of osteopaths not only provides new data for Austria but also allows comparisons with other European countries.

A voluntary, online-based, closed-ended survey was distributed across Austria in the period between April and August 2020. The original English OPERA questionnaire, composed of 52 questions in seven sections, was translated into German and adapted to the Austrian situation. Recruitment was performed through social media and an e-based campaign.

The survey was completed by 338 individuals (response rate ~26%), of which 239 (71%) were female. The median age of the responders was 40–49 years. Almost all had preliminary healthcare training, mainly in physiotherapy (72%). The majority of respondents were self-employed (88%) and working as sole practitioners (54%). The median number of consultations per week was 21–25 and the majority of respondents scheduled 46–60 minutes for each consultation (69%).

The most commonly used diagnostic techniques were: palpation of position/structure, palpation of tenderness, and visual inspection. The most commonly used treatment techniques were cranial, visceral, and articulatory/mobilization techniques. The majority of patients estimated by respondents consulted an osteopath for musculoskeletal complaints mainly localized in the lumbar and cervical region. Although the majority of respondents experienced a strong osteopathic identity, only a small proportion (17%) advertise themselves exclusively as osteopaths.

The authors concluded that this study represents the first published document to determine the characteristics of the osteopathic practitioners in Austria using large, national data. It provides new information on where, how, and by whom osteopathic care is delivered. The information provided may contribute to the evidence used by stakeholders and policy makers for the future regulation of the profession in Austria.

This paper reveals several findings that are, I think, noteworthy:

- Visceral osteopathy was used often or very often by 84% of the osteopaths.

- Muscle energy techniques were used often or very often by 53% of the osteopaths.

- Techniques applied to the breasts were used by 59% of the osteopaths.

- Vaginal techniques were used by 49% of the osteopaths.

- Rectal techniques were used by 39% of the osteopaths.

- “Taping/kinesiology tape” was used by 40% of osteopaths.

- Applied kinesiology was used by 17% of osteopaths and was by far the most-used diagnostic approach.

Perhaps the most worrying finding of the entire paper is summarized in this sentence: “Informed consent for oral techniques was requested only by 10.4% of respondents, and for genital and rectal techniques by 21.0% and 18.3% respectively.”

I am lost for words!

I fail to understand what meaningful medical purpose the fingers of an osteopath are supposed to have in a patient’s vagina or rectum. Surely, putting them there is a gross violation of medical ethics.

Considering these points, I find it impossible not to conclude that far too many Austrian osteopaths practice treatments that are implausible, unproven, potentially harmful, unethical, and illegal. If patients had the courage to take action, many of these charlatans would probably spend some time in jail.

Yesterday, the post brought me a nice Christmas present. For many months, I had been working on updating and extending a book of mine. Then there were some delays at the publisher, but now it is out – what a delight!

The previous edition contained my evidence-based assessments of 150 alternative modalities (therapies and diagnostic techniques). This already was by no means an easy task. The new edition has 202 short, easy-to-understand, and fully-referenced chapters, each on a different modality. I am quite proud of the achievement. Let me just show you the foreword to the new edition:

Alternative medicine is full of surprises. For me, a big surprise was that the first edition of this book was so successful that I was invited to do a second one. I do this, of course, with great pleasure.

So, what is new? I have made two main alterations. Firstly, I updated the previous text by adding new evidence where it had emerged. Secondly, I added many more modalities—52, to be exact.

To the best of my knowledge, this renders the new edition of this book the most comprehensive reference text on alternative medicine available to date. It informs you about the nature, proven benefits, and potential risks of 202 different diagnostic methods and therapeutic interventions from the realm of so-called alternative medicine. If you use this information wisely, it could save you a lot of money. One day, it might even save your life.

I hope you enjoy using this book as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Like the first edition, the book is not about promoting so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) nor about the opposite. It is about evaluating SCAM critically but fairly. In other words, each subject had to be researched and the evidence for or against it explained such that a layperson will comprehend it. This proved to be a colossal task.

The end result will not please the many believers in SCAM, I am afraid. Yet, I hope it will suit those who realize that, in healthcare, progress is generated not through belief but through critical evaluation of the evidence.

Earlier this year, I started the ‘WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION’. As a prize, I am offering the winner (that is the lead author of the winning paper) one of my books that best fits his/her subject. I am sure this will overjoy him or her. I hope to identify about 10 candidates for the prize, and towards the end of the year, I let my readers decide democratically on who should be the winner. In this spirit of democratic voting, let me suggest to you entry No 9. Here is the unadulterated abstract:

Background

With the increasing popularity of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) by the global community, how to teach basic knowledge of TCM to international students and improve the teaching quality are important issues for teachers of TCM. The present study was to analyze the perceptions from both students and teachers on how to improve TCM learning internationally.

Methods

A cross-sectional national survey was conducted at 23 universities/colleges across China. A structured, self-reported on-line questionnaire was administered to 34 Chinese teachers who taught TCM course in English and to 1016 international undergraduates who were enrolled in the TCM course in China between 2017 and 2021.

Results

Thirty-three (97.1%) teachers and 900 (88.6%) undergraduates agreed Chinese culture should be fully integrated into TCM courses. All teachers and 944 (92.9%) undergraduates thought that TCM had important significance in the clinical practice. All teachers and 995 (97.9%) undergraduates agreed that modern research of TCM is valuable. Thirty-three (97.1%) teachers and 959 (94.4%) undergraduates thought comparing traditional medicine in different countries with TCM can help the students better understand TCM. Thirty-two (94.1%) teachers and 962 (94.7%) undergraduates agreed on the use of practical teaching method with case reports. From the perceptions of the undergraduates, the top three beneficial learning styles were practice (34.3%), teacher’s lectures (32.5%), case studies (10.4%). The first choice of learning mode was attending to face-to-face teaching (82.3%). The top three interesting contents were acupuncture (75.5%), Chinese herbal medicine (63.8%), and massage (55.0%).

Conclusion

To improve TCM learning among international undergraduates majoring in conventional medicine, integration of Chinese culture into TCM course, comparison of traditional medicine in different countries with TCM, application of the teaching method with case reports, and emphasization of clinical practice as well as modern research on TCM should be fully considered.

I am impressed with this paper mainly because to me it does not make any sense at all. To be blunt, I find it farcically nonsensical. What precisely? Everything:

- the research question,

- the methodology,

- the conclusion

- the write-up,

- the list of authors and their affiliations: Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Basic Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Medical College, China Three Gorges University, Yichang, China, Basic Teaching and Research Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China, Institute of Integrative Medicine, Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, Department of Chinese Medicine/Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University, Shenyang, China, Department of Acupuncture, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, Teaching and Research Section of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shengli Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medicine University, Jinzhou, China, Department of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China.

- the journal that had this paper peer-reviewed and published.

But what impressed me most with this paper is the way the authors managed to avoid even the slightest hint of critical thinking. They even included a short paragraph in the discussion section where they elaborate on the limitations of their work without ever discussing the true flaws in the conception and execution of this extraordinary example of pseudoscience.

Is acupuncture more than a theatrical placebo? Acupuncture fans are convinced that the answer to this question is YES. Perhaps this paper will make them think again.

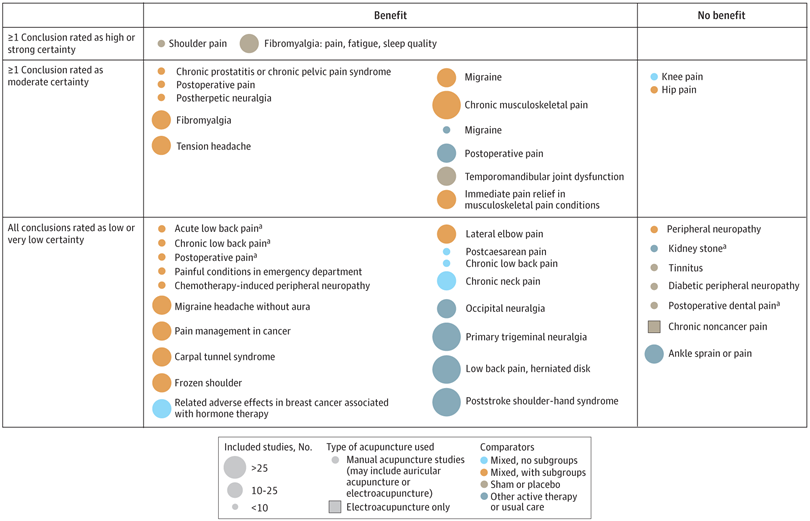

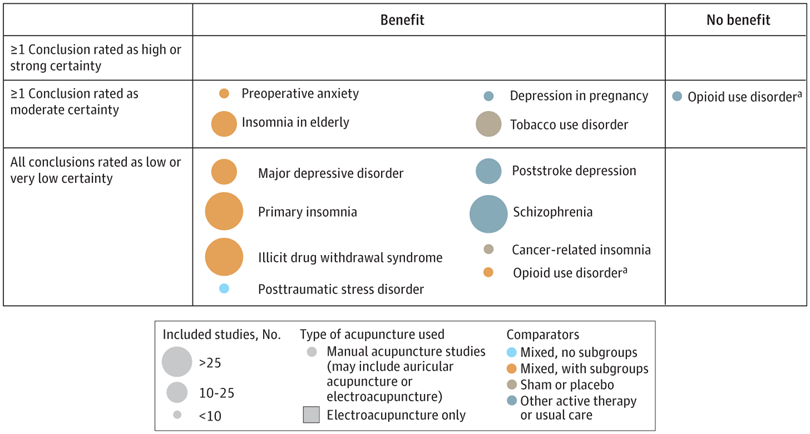

A new analysis mapped the systematic reviews, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence for outcomes of acupuncture as a treatment for adult health conditions. Computerized search of PubMed and 4 other databases from 2013 to 2021. Systematic reviews of acupuncture (whole body, auricular, or electroacupuncture) for adult health conditions that formally rated the certainty, quality, or strength of evidence for conclusions. Studies of acupressure, fire acupuncture, laser acupuncture, or traditional Chinese medicine without mention of acupuncture were excluded. Health condition, number of included studies, type of acupuncture, type of comparison group, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence. Reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as high-certainty evidence, reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as moderate-certainty evidence and reviews with all conclusions rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence; full list of all conclusions and certainty of evidence.

A total of 434 systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions were found; of these, 127 reviews used a formal method to rate the certainty or quality of evidence of their conclusions, and 82 reviews were mapped, covering 56 health conditions. Across these, there were 4 conclusions that were rated as high-certainty evidence and 31 conclusions that were rated as moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions (>60) were rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence. Approximately 10% of conclusions rated as high or moderate-certainty were that acupuncture was no better than the comparator treatment, and approximately 75% of high- or moderate-certainty evidence conclusions were about acupuncture compared with a sham or no treatment.

Three evidence maps (pain, mental conditions, and other conditions) are shown below

The authors concluded that despite a vast number of randomized trials, systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions have rated only a minority of conclusions as high- or moderate-certainty evidence, and most of these were about comparisons with sham treatment or had conclusions of no benefit of acupuncture. Conclusions with moderate or high-certainty evidence that acupuncture is superior to other active therapies were rare.

These findings are sobering for those who had hoped that acupuncture might be effective for a range of conditions. Despite the fact that, during recent years, there have been numerous systematic reviews, the evidence remains negative or flimsy. As 34 reviews originate from China, and as we know about the notorious unreliability of Chinese acupuncture research, this overall result is probably even more negative than the authors make it out to be.

Considering such findings, some people (including the authors of this analysis) feel that we now need more and better acupuncture trials. Yet I wonder whether this is the right approach. Would it not be better to call it a day, concede that acupuncture generates no or only relatively minor effects, and focus our efforts on more promising subjects?

An international team of researchers described retracted papers originating from paper mills, including their characteristics, visibility, and impact over time, and the journals in which they were published. The term paper mill refers to for-profit organizations that engage in the large-scale production and sale of papers to researchers, academics, and students who wish to, or have to, publish in peer-reviewed journals. Many paper mill papers included fabricated data.

All paper mill papers retracted from 1 January 2004 to 26 June 2022 were included in the study. Papers bearing an expression of concern were excluded. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and analyze the trend of retracted paper mill papers over time, and to analyze their impact and visibility by reference to the number of citations received.

In total, 1182 retracted paper mill papers were identified. The publication of the first paper mill paper was in 2004 and the first retraction was in 2016; by 2021, paper mill retractions accounted for 772 (21.8%) of the 3544 total retractions. Overall, retracted paper mill papers were mostly published in journals of the second highest Journal Citation Reports quartile for impact factor (n=529 (44.8%)) and listed four to six authors (n=602 (50.9%)). Of the 1182 papers, almost all listed authors of 1143 (96.8%) paper mill retractions came from Chinese institutions, and 909 (76.9%) listed a hospital as a primary affiliation. 15 journals accounted for 812 (68.7%) of 1182 paper mill retractions, with one journal accounting for 166 (14.0%). Nearly all (n=1083, 93.8%) paper mill retractions had received at least one citation since publication, with a median of 11 (interquartile range 5-22) citations received.

The authors concluded that papers retracted originating from paper mills are increasing in frequency, posing a problem for the research community. Retracted paper mill papers most commonly originated from China and were published in a small number of journals. Nevertheless, detected paper mill papers might be substantially different from those that are not detected. New mechanisms are needed to identify and avoid this relatively new type of misconduct.

China encourages its researchers to publish papers in return for money and career promotions. Furthermore, medical students at Chinese universities are required to produce a scientific paper in order to graduate. Paper mills openly advertise their services on the Internet and maintain a presence on university campuses. The authors of this analysis reference another recent article (authored by two Chinese researchers) that throws more light on the problem:

This study used data from the Retraction Watch website and from published reports on retractions and paper mills to summarize key features of research misconduct in China. Compared with publicized cases of falsified or fabricated data by authors from other countries of the world, the number of Chinese academics exposed for research misconduct has increased dramatically in recent years. Chinese authors do not have to generate fake data or fake peer reviews for themselves because paper mills in China will do the work for them for a price. Major retractions of articles by authors from China were all announced by international publishers. In contrast, there are few reports of retractions announced by China’s domestic publishers. China’s publication requirements for physicians seeking promotions and its leniency toward research misconduct are two major factors promoting the boom of paper mills in China.

As the authors of the new analysis point out: “Fraudulent papers have negative consequences for the scientific community and the general public, engendering distrust in science, false claims of drug or device efficacy, and unjustified academic promotion, among other problems.” On this blog, I have often warned of research originating from China (some might even think that this is becoming an obsession of mine but I do truly think that this is very important). While such fraudulent papers may have a relatively small impact in many areas of healthcare, their influence in the realm of TCM (where the majority of research comes from China) is considerable. In other words, TCM research is infested by fraud to a degree that prevents drawing meaningful conclusions about the value of TCM treatments.

I feel strongly that it is high time for us to do something about this precarious situation. Otherwise, I fear that in the near future no respectable scientist will take TCM seriously.

It has been reported that a naturopath from the US who sold fake COVID-19 immunization treatments and fraudulent vaccination cards during the height of the coronavirus pandemic has been sentenced to nearly three years in prison. Juli A. Mazi pleaded guilty last April in federal court in San Francisco to one count of wire fraud and one count of false statements related to health care matters. Now District Judge Charles R. Breyer handed down a sentence of 33 months, according to Joshua Stueve, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Justice. Mazi, of Napa, was ordered to surrender to the Bureau of Prisons on or before January 6, 2023.

The case is the first federal criminal fraud prosecution related to fraudulent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccination cards for COVID-19, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. In August, Breyer denied Mazi’s motion to withdraw her plea agreement after she challenged the very laws that led to her prosecution. Mazi, who fired her attorneys and ended up representing herself, last week filed a letter with the court claiming sovereign immunity. Mazi said that as a Native American she is “immune to legal action.”

She provided fake CDC vaccination cards for COVID-19 to at least 200 people with instructions on how to complete the cards to make them look like they had received a Moderna vaccine, federal prosecutors said. She also sold homeopathic pellets she fraudulently claimed would provide “lifelong immunity to COVID-19.” She told customers that the pellets contained small amounts of the virus and would create an antibody response. Mazi also offered the pellets in place of childhood vaccinations required for attendance at school and sold at least 100 fake immunization cards that said the children had been vaccinated, knowing the documents would be submitted to schools, officials said. Federal officials opened an investigation against Mazi after receiving a complaint in April 2021 to the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General hotline.

_______________________

On her website, Mazi states this about herself:

Juli Mazi received her doctorate in Naturopathic Medicine from the National University of Natural Medicine in Portland, Oregon where she trained in the traditional medical sciences as well as ancient and modern modalities that rely on the restorative power of Nature to heal. Juli Mazi radiates the vibrant health she is committed to helping her patients achieve. Juli’s positive outlook inspires confidence; her deep well of calm puts people at immediate ease. The second thing they notice is that truly she listens. Dr. Mazi’s very presence is healing.

On this site, she also advocates all sorts of treatments and ideas which I would call more than a little strange, for instance, coffee enemas:

Using a coffee enema is a time-tested remedy for detoxification, but it is not without risks. If you are not careful, the process can cause internal burns. In addition, improperly brewed coffee can lead to electrolyte imbalances and dehydration, and coffee enemas are not recommended for pregnant women or young children.

To make coffee enemas safe and effective, always choose quality organic coffee. A coffee enema should be free of toxins and pesticides. Use a reusable enema kit with stainless steel or silicone hosing for safety. Moreover, do not use a soft plastic or latex enema bags. It is also essential to limit the length of time that the coffee spends in the container.

A coffee enema should be held for 12 to 15 minutes and then released in the toilet. You may repeat the process as necessary. Usually, the procedure should be done once or twice a day. However, if you are experiencing acute toxicity, you can use a coffee enema as often as needed. Make sure you have had a bowel movement before making the coffee enema. Otherwise, the process may be hindered.

Perhaps the most interesting thing on her website is her advertisement of the fact that her peers not just tolerate such eccentricities but gave Mazi an award for ‘BEST ALTERNATIVE HEALTH & BEST GENERAL PRACTITIONER’.

To me, this suggests that US ‘doctors of naturopathy’ and their professional organizations live on a different planet, a planet where evidence counts for nothing and dangerously misleading patients seems to be the norm.

Today, you cannot read a newspaper or listen to the radio without learning that there has been a significant, sensational, momentous, unprecedented, etc. breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The reason for all this excitement (or is it hype?) is this study just out in the NEJM:

BACKGROUND

The accumulation of soluble and insoluble aggregated amyloid-beta (Aβ) may initiate or potentiate pathologic processes in Alzheimer’s disease. Lecanemab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to Aβ soluble protofibrils, is being tested in persons with early Alzheimer’s disease.

METHODS

We conducted an 18-month, multicenter, double-blind, phase 3 trial involving persons 50 to 90 years of age with early Alzheimer’s disease (mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease) with evidence of amyloid on positron-emission tomography (PET) or by cerebrospinal fluid testing. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive intravenous lecanemab (10 mg per kilogram of body weight every 2 weeks) or placebo. The primary end point was the change from baseline at 18 months in the score on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB; range, 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating greater impairment). Key secondary end points were the change in amyloid burden on PET, the score on the 14-item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog14; range, 0 to 90; higher scores indicate greater impairment), the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS; range, 0 to 1.97; higher scores indicate greater impairment), and the score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment (ADCS-MCI-ADL; range, 0 to 53; lower scores indicate greater impairment).

RESULTS

A total of 1795 participants were enrolled, with 898 assigned to receive lecanemab and 897 to receive placebo. The mean CDR-SB score at baseline was approximately 3.2 in both groups. The adjusted least-squares mean change from baseline at 18 months was 1.21 with lecanemab and 1.66 with placebo (difference, −0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.67 to −0.23; P<0.001). In a substudy involving 698 participants, there were greater reductions in brain amyloid burden with lecanemab than with placebo (difference, −59.1 centiloids; 95% CI, −62.6 to −55.6). Other mean differences between the two groups in the change from baseline favoring lecanemab were as follows: for the ADAS-cog14 score, −1.44 (95% CI, −2.27 to −0.61; P<0.001); for the ADCOMS, −0.050 (95% CI, −0.074 to −0.027; P<0.001); and for the ADCS-MCI-ADL score, 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2 to 2.8; P<0.001). Lecanemab resulted in infusion-related reactions in 26.4% of the participants and amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema or effusions in 12.6%.

CONCLUSIONS

Lecanemab reduced markers of amyloid in early Alzheimer’s disease and resulted in moderately less decline on measures of cognition and function than placebo at 18 months but was associated with adverse events. Longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. (Funded by Eisai and Biogen; Clarity AD ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03887455. opens in new tab.)

It’s a good study, and I (like everyone else) hope that it will mean tangible progress in the management of that devastating disease. Most media outlets are announcing the news with the claim that it is the FIRST TIME that any treatment has been shown to delay the cognitive decline of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

But is this true?

I think not!

There have been several studies showing that the herbal remedy GINKGO BILOBA slows the Alzheimer-related decline. Here is the latest systematic review of the subject:

Background: Ginkgo biloba is a natural medicine used for cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. The objective of this review is to explore the effectiveness and safety of Ginkgo biloba in treating mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods: Electronic search was conducted from PubMed, Cochrane Library, and four major Chinese databases from their inception up to 1(st) December, 2014 for randomized clinical trials on Ginkgo biloba in treating mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. Meta-analyses were performed by RevMan 5.2 software.

Results: 21 trials with 2608 patients met the inclusion criteria. The general methodological quality of included trials was moderate to poor. Compared with conventional medicine alone, Ginkgo biboba in combination with conventional medicine was superior in improving Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores at 24 weeks for patients with Alzheimer’s disease (MD 2.39, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.50, P<0.0001) and mild cognitive impairment (MD 1.90, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.39, P<0.00001), and Activity of Daily Living (ADL) scores at 24 weeks for Alzheimer’s disease (MD -3.72, 95% CI -5.68 to -1.76, P=0.0002). When compared with placebo or conventional medicine in individual trials, Ginkgo biboba demonstrated similar but inconsistent findings. Adverse events were mild.

Conclusion: Ginkgo biloba is potentially beneficial for the improvement of cognitive function, activities of daily living, and global clinical assessment in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. However, due to limited sample size, inconsistent findings and methodological quality of included trials, more research are warranted to confirm the effectiveness and safety of ginkgo biloba in treating mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

I know, the science is not nearly as good as that of the NEJM trial. I also know that the trial data for ginkgo biloba are not uniformly positive. And I know that, after several studies showed good results, later trials tended not to confirm them.

But this is what very often happens in clinical research: studies are initially promising, only to be disappointing as more studies emerge. I sincerely hope that this will not happen with the new drug ‘Lecanemab’ and that today’s excitement will not turn out to be hype.

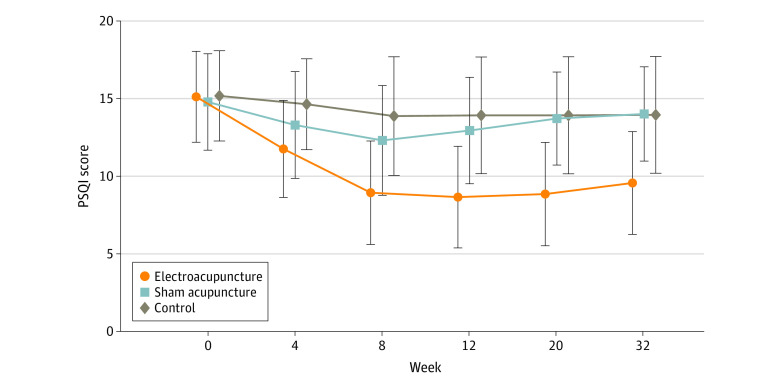

Electroacupuncture (EA) is often advocated for depression and sleep disorders but its efficacy remains uncertain. The aim of this study was, therefore, to “assess the efficacy and safety of EA as an alternative therapy in improving sleep quality and mental state for patients with insomnia and depression.”

A 32-week patient- and assessor-blinded, randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial (8-week intervention plus 24-week follow-up) was conducted from September 1, 2016, to July 30, 2019, at 3 tertiary hospitals in Shanghai, China. Patients were randomized to receive

- EA treatment and standard care,

- sham acupuncture (SA) treatment and standard care,

- standard care only as control.

Patients in the EA or SA groups received a 30-minute treatment 3 times per week (usually every other day except Sunday) for 8 consecutive weeks. All treatments were performed by licensed acupuncturists with at least 5 years of clinical experience. A total of 6 acupuncturists (2 at each center; including X.Y. and S.Z.) performed EA and SA, and they received standardized training on the intervention method before the trial. The regular acupuncture method was applied at the Baihui (GV20), Shenting (GV24), Yintang (GV29), Anmian (EX-HN22), Shenmen (HT7), Neiguan (PC6), and SanYinjiao (SP6) acupuncture points, with 0.25 × 25-mm and 0.30 × 40-mm real needles (Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd), or 0.30 × 30-mm sham needles (Streitberger sham device [Asia-med GmbH]).

For patients in the EA group, rotating or lifting-thrusting manipulation was applied for deqi sensation after needle insertion. The 2 electrodes of the electrostimulator (CMNS6-1 [Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd]) were connected to the needles at GV20 and GV29, delivering a continuous wave based on the patient’s tolerance. Patients in the SA group felt a pricking sensation when the blunt needle tip touched the skin, but without needle insertion. All indicators of the nearby electrostimulator were set to 0, with the light switched on. Standard care (also known as treatment as usual or routine care) was used in the control group. Patients receiving standard care were recommended by the researchers to get regular exercise, eat a healthy diet, and manage their stress level during the trial. They were asked to keep the regular administration of antidepressants, sedatives, or hypnotics as well. Psychiatrists in the Shanghai Mental Health Center (including X.L.) guided all patients’ standard care treatment and provided professional advice when a patient’s condition changed.

The primary outcome was change in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) from baseline to week 8. Secondary outcomes included PSQI at 12, 20, and 32 weeks of follow-up; sleep parameters recorded in actigraphy; Insomnia Severity Index; 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score; and Self-rating Anxiety Scale score.

Among the 270 patients (194 women [71.9%] and 76 men [28.1%]; mean [SD] age, 50.3 [14.2] years) included in the intention-to-treat analysis, 247 (91.5%) completed all outcome measurements at week 32, and 23 (8.5%) dropped out of the trial. The mean difference in PSQI from baseline to week 8 within the EA group was -6.2 (95% CI, -6.9 to -5.6). At week 8, the difference in PSQI score was -3.6 (95% CI, -4.4 to -2.8; P < .001) between the EA and SA groups and -5.1 (95% CI, -6.0 to -4.2; P < .001) between the EA and control groups. The efficacy of EA in treating insomnia was sustained during the 24-week postintervention follow-up. Significant improvement in the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (-10.7 [95% CI, -11.8 to -9.7]), Insomnia Severity Index (-7.6 [95% CI, -8.5 to -6.7]), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (-2.9 [95% CI, -4.1 to -1.7]) scores and the total sleep time recorded in the actigraphy (29.1 [95% CI, 21.5-36.7] minutes) was observed in the EA group during the 8-week intervention period (P < .001 for all). No between-group differences were found in the frequency of sleep awakenings. No serious adverse events were reported.

The result of the blinding assessment showed that 56 patients (62.2%) in the SA group guessed wrongly about their group assignment (Bang blinding index, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.3]), whereas 15 (16.7%) in the EA group also guessed wrongly (Bang blinding index, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.4-0.7]). This indicated a relatively higher degree of blinding in the SA group.

The authors concluded that, in this randomized clinical trial of EA treatment for insomnia in patients with depression, quality of sleep improved significantly in the EA group compared with the SA or control group at week 8 and was sustained at week 32.

This trial seems rigorous, it has a sizable sample size, uses a credible placebo procedure, and is reported in sufficient detail. Why then am I skeptical?

- Perhaps because we have often discussed how untrustworthy acupuncture studies from China are?

- Perhaps because I fail to see a plausible mechanism of action?

- Perhaps because the acupuncturists could not be blinded and thus might have influenced the outcome?

- Perhaps because the effects of sham acupuncture seem unreasonably small?

- Perhaps because I cannot be sure whether the acupuncture or the electrical current is supposed to have caused the effects?

- Perhaps because the authors of the study are from institutions such as the Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Huadong Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai,

- Perhaps because the results seem too good to be true?

If you have other and better reasons, I’d be most interested to hear them.

The Sunday Times reported yesterday reported that five NHS trusts currently offer moxibustion to women in childbirth for breech babies, i.e. babies presenting upside down. Moxibustion is a form of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) where mugwort is burned close to acupuncture points. The idea is that this procedure would stimulate the acupuncture point similar to the more common way using needle insertion. The fifth toe is viewed as the best traditional acupuncture point for breech presentation, and the treatment is said to turn the baby in the uterus so that it can be delivered more easily.

At least four NHS trusts are offering acupuncture and reflexology with aromatherapy to help women with delayed pregnancies, while 15 NHS trusts offer hypnobirthing classes. Some women are asked to pay fees of up to £140 for it. These treatments are supposed to relax the mother in the hope that this will speed up the process of childbirth.

The Nice guidelines on maternity care say the NHS should not offer acupuncture, acupressure, or hypnosis unless specifically requested by women. The reason for the Nice warning is simple: there is no convincing evidence that these therapies are effective.

Campaigner Catherine Roy who compiled the list of treatments said: “To one degree or another, the Royal College of Midwives, the Care Quality Commission and parts of the NHS support these pseudoscientific treatments.

“They are seen as innocuous but they carry risks, can delay medical help and participate in an anti-medicalisation stance specific to ‘normal birth’ ideology and maternity care. Nice guidelines are clear that they should not be offered by clinicians for treatment. NHS England must ensure that pseudoscience and non-evidence based treatments are removed from NHS maternity care.”

Birte Harlev-Lam, executive director of the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), said: “We want every woman to have as positive an experience during pregnancy, labour, birth and the postnatal period as possible — and, most importantly, we want that experience to be safe. That is why we recommend all maternity services to follow Nice guidance and for midwives to practise in line with the code set out by the Nursing and Midwifery Council.”

A spokeswoman for Nice said it was reviewing its maternity guidelines. NHS national clinical director for maternity and women’s health, Dr Matthew Jolly, said: “All NHS services are expected to offer safe and personalised clinical care and local NHS areas should commission core maternity services using the latest NICE and clinical guidance. NHS trusts are under no obligation to provide complementary or alternative therapies on top of evidence-based clinical care, but where they do in response to the wishes of mothers it is vital that the highest standards of safety are maintained.”

On this blog, we have repeatedly discussed the strange love affair of midwives with so-called alternative medicine (SCAM), for instance, here. In 2012, we published a summary of 19 surveys on the subject. It showed that the prevalence of SCAM use varied but was often close to 100%. Much of it did not seem to be supported by strong evidence for efficacy. We concluded that most midwives seem to use SCAM. As not all SCAMs are without risks, the issue should be debated openly. Today, there is plenty more evidence to show that the advice of midwives regarding SCAM is not just not evidence-based but also often dangerous. This, of course, begs the question: when will the professional organizations of midwifery do something about it?

This double-blind, randomized study assessed the effectiveness of physiotherapy instrument mobilization (PIM) in patients with low back pain (LBP) and compared it with the effectiveness of manual mobilization.

Thirty-two participants with LBP were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- The PIM group received lumbar mobilization using an activator instrument, stabilization exercises, and education.

- The manual group received lumbar mobilization using a pisiform grip, stabilization exercises, and education.

Both groups had 4 treatment sessions over 2-3 weeks. The following outcomes were measured before the intervention, and after the first and fourth sessions:

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS),

- Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scale,

- Pressure pain threshold (PPT),

- lumbar spine range of motion (ROM),

- lumbar multifidus muscle activation.

There were no differences between the PIM and manual groups in any outcome measures. However, over the period of study, there were improvements in both groups in NPRS (PIM: 3.23, Manual: 3.64 points), ODI (PIM: 17.34%, Manual: 14.23%), PPT (PIM: ⩽ 1.25, Manual: ⩽ 0.85 kg.cm2), lumbar spine ROM (PIM: ⩽ 9.49∘, Manual: ⩽ 0.88∘), and/or lumbar multifidus muscle activation (percentage thickness change: PIM: ⩽ 4.71, Manual: ⩽ 4.74 cm; activation ratio: PIM: ⩽ 1.17, Manual: ⩽ 1.15 cm).

The authors concluded that both methods of lumbar spine mobilization demonstrated comparable improvements in pain and disability in patients with LBP, with neither method exhibiting superiority over the other.

If this conclusion is meant to tell us that both treatments were equally effective, I beg to differ. The improvements documented here are consistent with improvements caused by the natural history of the condition, regression towards the mean, and placebo effects. The data do not prove that they are due to the treatments. On the contrary, they seem to imply that patients get better no matter what therapy is used. Thus, I feel that the results are entirely in keeping with the hypothesis that spinal mobilization is a placebo treatment.

So, allow me to re-phrase the authors’ conclusion as follows:

Lumbar mobilizations do not seem to have specific therapeutic effects and might therefore be considered to be ineffective for LBP.