clinical trial

Should Acupuncture-Related Therapies be Considered in Prediabetes Control?

No!

If you are pre-diabetic, consult a doctor and follow his/her advice. Do NOT do what acupuncturists or other self-appointed experts tell you. Do NOT become a victim of quackery.

But the authors of a new paper disagree with my view.

So, let’s have a look at the evidence.

Their systematic review was aimed at evaluating the effects and safety of acupuncture-related therapy (AT) interventions on glycemic control for prediabetes. The Chinese researchers searched 14 databases and 5 clinical registry platforms from inception to December 2020. Randomized controlled trials involving AT interventions for managing prediabetes were included.

Of the 855 identified trials, 34 articles were included for qualitative synthesis, 31 of which were included in the final meta-analysis. Compared with usual care, sham intervention, or conventional medicine, AT treatments yielded greater reductions in the primary outcomes, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (standard mean difference [SMD] = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.06, -0.61; P < .00001), 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) (SMD = -0.88; 95% CI, -1.20, -0.57; P < .00001), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (SMD = -0.91; 95% CI, -1.31, -0.51; P < .00001), as well as a greater decline in the secondary outcome, which is the incidence of prediabetes (RR = 1.43; 95% CI, 1.26, 1.63; P < .00001).

The authors concluded that AT is a potential strategy that can contribute to better glycemic control in the management of prediabetes. Because of the substantial clinical heterogeneity, the effect estimates should be interpreted with caution. More research is required for different ethnic groups and long-term effectiveness.

But this is clearly a positive result!

Why do I not believe it?

There are several reasons:

- There is no conceivable mechanism by which AT prevents diabetes.

- The findings heavily rely on Chinese RCTs which are known to be of poor quality and often even fabricated. To trust such research would be a dangerous mistake.

- Many of the primary studies were designed such that they failed to control for non-specific effects of AT. This means that a causal link between AT and the outcome is doubtful.

- The review was published in a 3rd class journal of no impact. Its peer-review system evidently failed.

So, let’s just forget about this rubbish paper?

If only it were so easy!

Journalists always have a keen interest in exotic treatments that contradict established wisdom. Predictably, they have been reporting about the new review thus confusing or misleading the public. One journalist, for instance, stated:

Acupuncture has been used for thousands of years to treat a variety of illnesses — and now it could also help fight one of the 21st century’s biggest health challenges.

New research from Edith Cowan University has found acupuncture therapy may be a useful tool in avoiding type 2 diabetes.

The team of scientists investigated dozens of studies covering the effects of acupuncture on more than 3600 people with prediabetes. This is a condition marked by higher-than-normal blood glucose levels without being high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes.

According to the findings, acupuncture therapy significantly improved key markers, such as fasting plasma glucose, two-hour plasma glucose, and glycated hemoglobin. Additionally, acupuncture therapy resulted in a greater decline in the incidence of prediabetes.

The review can thus serve as a prime example for demonstrating how irresponsible research has the power to mislead millions. This is why I have often said that poor research is a danger to public health.

And what can be done about this more and more prevalent problem?

The answer is easy: people need to behave more responsibly; this includes:

- trialists,

- review authors,

- editors,

- peer-reviewers,

- journalists.

Yes, the answer is easy in theory – but the practice is far from it!

The ‘My Resilience in Adolescence (MYRIAD) Trial’evaluated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SBMT compared with teaching-as-usual (TAU).

MYRIAD was a parallel group, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Eighty-five eligible schools consented and were randomized 1:1 to TAU (43 schools, 4232 students) or SBMT (42 schools, 4144 students), stratified by school size, quality, type, deprivation, and region. Schools and students (mean (SD); age range=12.2 (0.6); 11–14 years) were broadly UK population-representative. Forty-three schools (n=3678 pupils; 86.9%) delivering SBMT, and 41 schools (n=3572; 86.2%) delivering TAU, provided primary end-point data. SBMT comprised 10 lessons of psychoeducation and mindfulness practices. TAU comprised standard social-emotional teaching. Participant-level risk for depression, social-emotional-behavioural functioning and well-being at 1 year follow-up were the co-primary outcomes. Secondary and economic outcomes were included.

An analysis of the data from 84 schools (n=8376 participants) found no evidence that SBMT was superior to TAU at 1 year. Standardised mean differences (intervention minus control) were: 0.005 (95% CI −0.05 to 0.06) for risk for depression; 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.07) for social-emotional-behavioural functioning; and 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) for well-being. SBMT had a high probability of cost-effectiveness (83%) at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20 000 per quality-adjusted life year. No intervention-related adverse events were observed.

An analysis of the data from 84 schools (n=8376 participants) found no evidence that SBMT was superior to TAU at 1 year. Standardised mean differences (intervention minus control) were: 0.005 (95% CI −0.05 to 0.06) for risk for depression; 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.07) for social-emotional-behavioural functioning; and 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) for well-being. SBMT had a high probability of cost-effectiveness (83%) at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20 000 per quality-adjusted life year. No intervention-related adverse events were observed.

The authors concluded that the findings do not support the superiority of SBMT over TAU in promoting mental health in adolescence.

Even though the results are negative, MYRIAD must be praised for its scale and rigor, and for highlighting the importance of large, well-designed studies before implementing measures of this kind on a population basis. Co-author Tim Dalgliesh, director of the Cambridge Centre for Affective Disorders, said: “For policymakers, it’s not just about coming up with a great intervention to teach young people skills to deal with their stress. You also have to think about where that stress is coming from in the first place.”

“There had been some hope for an easy solution, especially for those who might develop depression,” says Til Wykes, head of the School of Mental Health and Psychological Sciences at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King’s College London. “There may be lots of reasons for developing depression, and these are probably not helped by mindfulness,” she says. “We need more research on other potential factors that might be modified, and perhaps this would provide a more targeted solution to this problem.”

Personally, I feel that mindfulness has been hyped in recent years. Much of the research that seemed to support it was less than rigorous. What is now needed is a realistic approach based on sound evidence and critical thinking.

Third molar extraction is a painful treatment and thus is often used to investigate the effects of analgesics on pain. Hypnotherapy is said to help to reduce pain and to decrease the intake of postoperative systemic analgesics. Therefore, it seems reasonable to study the effects of hypnotherapy on the pain caused by third molar extraction.

In this study, the effectiveness of a brief hypnotic induction for patients undergoing third molar extractions was investigated. Data were collected from 33 patients with third molar extractions on the right and left sides. Patients received two different types of interventions in this monocentric randomized crossover trial. Third molar extraction was conducted on one side with reduced preoperative local anesthetics and an additional brief hypnotic induction (Dave Elman technique). The other side was conducted with regular preoperative local anesthetics without a brief hypnotic induction (standard care). Intake of postoperative systemic analgesics was allowed in both treatments.

Patients’ expectations about hypnosis were assessed at baseline. The primary outcome was the area under the curve with respect to ground of pain intensity after the treatment. Secondary outcomes were the amount of postoperative analgesics consumed and the preferred treatment.

There was no evidence that the area under the curve with respect to ground of pain differed between the two interventions (controlling for gender). There was, however, evidence to show that the patients’ expectations affected the effectiveness of the brief hypnotic induction. This means that patients with high expectations about hypnosis benefit more from treatment with reduced preoperative local anesthetics and additional brief hypnotic induction.

The authors concluded that, in this study, additional a brief hypnotic induction with reduced preoperative local anesthetic use did not generally reduce posttreatment pain after third molar extraction more than regular local anesthetics. The expectation of the patients about the effectiveness of hypnosis affected the effectiveness of the brief hypnotic induction so that patients with high expectations had a larger benefit from a brief hypnotic induction than patients with low expectations.

The most interesting findings here are, in my view, that:

- Hypnotherapy is not as effective as many enthusiasts claim.

- Expectation influences the outcome of hypnotherapy.

Expectation is, of course, a determinant of the size of the placebo response. Thus, this finding is interesting but far from unexpected. I would go as far as postulating that similar results would be obtained with most treatments regardless of whether they are alternative or conventional. The difference is that, in the case of alternative therapies, the expectation is a major (if not the only) determinant of the outcome, while it merely somewhat improves the outcome of an effective treatment. To put it differently, so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) relies entirely/mostly on expectation, while conventional medicine does not.

Earlier this year, I started the ‘WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION’. You will ask what is there to win in this competition? I agree: a competition without a prize is no fun. Therefore, I suggest offering the winner (that is the author of the winning paper) one of my books that best fits his/her subject. I am sure this will over-joy him or her. And how do we identify the winner? I suggest that I continue blogging about nominated papers (I hope to identify about 10 in total), and towards the end of the year, I let my readers decide democratically.

In this spirit of democratic voting, let me suggest to you ENTRY No 6:

This study was to ascertain the efficacy of dry cupping therapy (DCT) and optimal cup application time duration for cervical spondylosis (CS). It was designed as a randomized clinical trial involving 45 participants with clinically diagnosed CS. The eligible subjects were randomly allocated into three groups, each having 15 participants. Each of the three groups, i.e., A, B, and C, received DCT daily for 15 days for 8 min, 10 min, and 12 min, respectively. All the participants were evaluated at the baseline, 7th, and 15th day of the trial using the neck disability index (NDI) as well as the visual analog scale (VAS).

The baseline means ± SD of NDI and VAS scores were significantly reduced in all three groups at the end of the trial. Although all three groups were statistically equal in terms of NDI, group C demonstrated greater efficacy in terms of VAS.

The authors concluded that the per-protocol analysis showed that dry cupping effectively alleviated neck pain across all treatment groups. Although this effect on neck disability index was statistically equal in all three groups, the 12-min protocol was more successful in reducing pain.

Who would design such a study and why?

- The authors claim they wanted to ascertain the efficacy of DCT. A trial is for testing, not ascertaining. And this study does certainly not test for efficacy.

- The groups were too small to generate a meaningful result of what, in fact, was an equivalence study.

- Intra-group changes in symptoms between baseline and time points during treatment are irrelevant in a controlled trial.

- The slightly better results of group C are most likely due to chance or non-specific effects (a longer application of a placebo would generate better outcomes that a shorter one).

- The study participants had cervical spondylosis, yet the conclusion is about neck pain. The two are not identical.

- The title of the paper promises that we learn something about the safety of DCT. Sadly, a trial with just 45 patients has no chance in hell to pick up adverse effects in a reliable way.

- As there is no control group, the study cannot tell us anything about possible specific effects of DCT.

The authors of the study have impressive affiliations:

- Department of Ilaj bil Tadbir, Luqman Unani Medical College Hospital and Research Center, Bijapur, India.

- Department of Ilaj bil Tadbir, National Institute of Unani Medicine, Bengaluru, India.

- Department of Moalajat, Luqman Unani Medical College Hospital and Research Center, Bijapur, India.

I would have hoped that researchers from national institutions and medical colleges should be able to design a trial that has at least a small chance to produce a meaningful finding. As it turns out, my hope was badly disappointed.

Crystal healing is the treatment of all types of illnesses via the ‘healing energy’ of gemstones. It is as implausible as so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) gets. In my recent analysis of 150 SCAMs, I concluded that “there are no rigorous trials testing the therapeutic value of crystal healing”. This assumption is further confirmed by published papers like this one:

Recently, crystal healing and gemstone therapy, also known as litho- or gemmotherapy, is extensively promoted in the media, newspapers and the internet. There is also a growing interest of cancer patients in this unconventional treatment, resulting in the need for oncologists to give informed advice to their patients and to prevent them from wasting hope, time and money in an ineffective treatment, and at worst to postpone the necessary treatment of this life threatening disease. In the context of the currently ever-growing New-Age wave, believing in crystal healing has spread widely in the population. It is a historical belief similar to that of charmstones, rather than one based on modern scientific practices and advances. Pleasant feelings or seeming successes of crystal healing can be attributed to the strong placebo effect, or the believers wanting it to be true and seeing only things that back that up: cognitive bias. A scientific proof of any positive effect beyond a placebo effect does not exist. Even though this treatment can be generally regarded as harmless and without toxicity, it should not be recommended to cancer patients. Thereby we will help prevent our patients from wasting hope, time and money in an ineffective treatment, and at worst to postpone the necessary treatment of this life threatening disease, resulting in a worsened prognosis.

Yet, it seems that we were not entirely correct. Recently, I came across an article that mentions such a study:

A study conducted in 2001 by British psychologist Christopher French challenged 80 volunteers to differentiate between real and fake crystals after holding them in their hands for five minutes and meditating. Six people felt nothing at all, and the rest reported feeling some energy, whether in the form of tingling in the body or an improved sense of wellbeing. Both groups, though—whether holding the fake crystals or the real ones—reported similar impressions, suggesting the placebo effect could be at play.

“When scientists conduct robust clinical trials, they want to strip the intervention of these placebo effects to figure out if it has a specific benefit,” Jarry explains. “Alternative medicine’s reputation benefits strongly from these non-specific placebo effects. Enough people will start to feel better after using crystals (because of regression to the mean, self-limiting illness, misremembering, etc.), and they will publicly testify to their improvement, giving the illusion that crystals work. What they don’t know is what would have happened had they not used the crystals.”

So, if you want to keep a hunk of amethyst at your desk to alleviate your grief, or a Tiger’s Eye stone to clear the mind, go ahead: they may not be manipulating a sacred energy field around your body to heal you, but they can certainly manipulate your mind.

Unfortunately, the link provided does not lead directly to the study but to the publication list of Chris French. This in turn leads us to the reference in question:

French, C. C., O’Donnell, H., & Williams, L. (2001). Hypnotic susceptibility, paranormal belief and reports of ‘crystal power’. British Psychological Society Centenary Annual Conference, Glasgow, 28-31 March 2001. (Abstract published in Proceedings of the British Psychological Society, 9(2), 186).

Sadly, I cannot find the paper online and I suspect it exists only as an abstract in a conference book (I have emailed Chris and asked him). In any case, his study did not test the therapeutic value; so, my above statement is not entirely false.

In 2007, we published a systematic review summarizing the efficacy of homeopathic remedies used as a sole or additional therapy in cancer care. We have searched the literature using the databases: Amed (from 1985); CINHAL (from 1982); EMBASE (from 1974); Medline (from 1951); and CAMbase (from 1998). Randomized and non-randomized controlled clinical trials including patients with cancer or past experience of cancer receiving single or combined homeopathic interventions were included. The methodological quality of the trials was assessed by Jadad score. Six studies met our inclusion criteria (five were randomized clinical trials and one was a non-randomized study); but the methodological quality was variable including some high-standard studies. Our analysis of published literature on homeopathy thus found insufficient evidence to support the clinical efficacy of homeopathic therapy in cancer care.

Meanwhile, more trials have emerged, not least a dubious study by Frass et al which is currently under investigation. This means that a new evaluation of the totality of the available evidence might be called for. I am pleased to report that such an assessment has just been published.

In this systematic review, the researchers included clinical studies from 1800 until 2020 to evaluate evidence of the effectiveness of homeopathy on physical and mental conditions in patients during oncological treatment.

In February 2021 a systematic search was conducted searching five electronic databases (Embase, Cochrane, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Medline) to find studies concerning the use, effectiveness, and potential harm of homeopathy in cancer patients.

From all 1352 search results, 18 studies with 2016 patients were included in this SR. The patients treated with homeopathy were mainly diagnosed with breast cancer. The therapy concepts include single and combination homeopathic remedies (used systemically or as mouth rinses) of various dilutions. Outcomes assessed were the influence on toxicity of cancer treatment (mostly hot flashes and menopausal symptoms), time to drain-removal in breast cancer patients after mastectomy, survival, quality of life, global health and subjective well-being, anxiety, and depression as well as safety and tolerance.

The included studies reported heterogeneous results: some studies described significant differences in quality of life or toxicity of cancer treatment favoring homeopathy, whereas others did not find an effect or reported significant differences to the disadvantage of homeopathy or side effects caused by homeopathy. The majority of the studies have low methodological quality.

The authors concluded that, for homeopathy, there is neither a scientifically based hypothesis of its mode of action nor conclusive evidence from clinical studies in cancer care.

I predict that, if we wait another 15 years, we will have even more studies. I also predict that some of them will be less than reliable or even fake. Finally, I predict that the overall result will still be mixed and unconvincing.

Why can I be so sure?

- Because homeopathy lacks biological plausibility as a treatment of cancer (or any other condition).

- Because highly diluted homeopathic remedies are pure placebos.

- Because homeopathy has developed into a cult where one is no longer surprised to see studies emerging that are too good to be true.

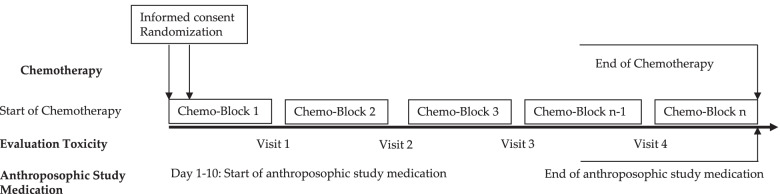

This multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial assessed the effects of anthroposophic treatments on toxicity related to intensive-phase chemotherapy treatment in children aged 1-18 with the primary outcome of the toxicity sum score. Secondary outcomes were chemotherapy-related toxicity, overall and event-free survival after 5 years in study patients.

The main sponsorship for the study was provided by: Helixor Heilmittel GmbH & Co. KG, Rosenfeld. Additional finacial support was provided by: WALA Heilmittel GmbH, Bad Boll/Eckwälden; Weleda AG, Schwäbisch Gmünd: Mahle Stiftung, Stuttgart; Software AG Stiftung, Darmstadt; Stiftung Helixor, Rosenfeld; and Injex Pharma AG, Berlin.

The intervention and control groups were both given standard chemotherapy according to malignancy & tumor type. The intervention arm was provided with anthroposophic supportive treatment (AST); given as anthroposophic base medication (AMP), as a base medication for all patients, and additional on-demand treatment tailored to the patient in the intervention groups. The control was given no AMP. The toxicity sum score (TSS) was assessed using NCI-CTC scales.

The AST consisted of base AMP including Helixor®, and on-demand supplementary AMP given as needed for symptoms. Administration of the AST intervention and chemotherapy protocol were tailored for each type of pediatric malignancy included in the trial. This included both the base and the on-demand AMP, which were administered based on acute symptoms during intensive chemotherapy. The intervention group started the AST between the day of randomization and day 10 of the first chemotherapy cycle.

Data of 288 patients could be analyzed. The analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the AST and the control group for the primary endpoint or the toxicity measures (secondary endpoints). Furthermore, groups did not differ significantly in the five-year overall and event-free survival follow-up.

The authors concluded that their findings showed that AST was able to be safely administered in a clinical setting, although no beneficial effects of AST between group toxicity scores, overall or event-free survival were shown.

In their discussion section, the authors explain the findings more clearly: “In the long term follow up, the explorative analysis of the data available for the 5-year follow up found no indications that efficacy of chemotherapy was influenced by AST. For long-term toxicities there were also no indications of an influence of AST.”

Question: what do we call a treatment that has neither adverse nor beneficial effects?

Could it be

PLACEBO?

It seems that no ancient treatment is daft enough for some researchers of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) to not pick it up. Even bloodletting is back, it seems!

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of therapeutic phlebotomy on ambulatory blood pressure in patients with grade 1 hypertension. In this randomized-controlled intervention study, patients with unmedicated hypertension grade 1 were randomized into an intervention group (phlebotomy group; 500 mL bloodletting at baseline and after 6 weeks) and a control group (waiting list) and followed up for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was the 24-h ambulatory mean arterial pressure between the intervention and control groups after 8 weeks. Secondary outcome parameters included ambulatory/resting systolic/diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and selected laboratory parameters (e.g., hemoglobin, hematocrit, erythrocytes, and ferritin). Resting systolic/diastolic blood pressure/heart rate and blood count were also assessed at 6 weeks before the second phlebotomy to ensure safety. A per-protocol analysis was performed.

Fifty-three hypertension participants (56.7 ± 10.5 years) were included in the analysis (n = 25 intervention group, n = 28 control group). The ambulatory measured mean arterial pressure decreased by -1.12 ± 5.16 mmHg in the intervention group and increased by 0.43 ± 3.82 mmHg in the control group (between-group difference: -1.55 ± 4.46, p = 0.22). Hemoglobin, hematocrit, erythrocytes, and ferritin showed more pronounced reductions in the intervention group in comparison with the control group, with significant between-group differences. Subgroup analysis showed trends regarding the effects on different groups classified by serum ferritin concentration, body mass index, age, and sex. Two adverse events (AEs) (anemia and dizziness) occurred in association with the phlebotomy, but no serious AEs.

The authors concluded that therapeutic phlebotomy resulted in only minimal reductions of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure measurement values in patients with unmedicated grade 1 hypertension. Further high-quality clinical studies are warranted, as this finding contradicts the results of other studies.

This paper requires a few short comments:

- The effect on blood pressure was not ‘minimal’, as the authors pretend, it was non-existent (i.e. not significant and due to chance only).

- This lack of effect had to be expected considering human physiology.

- The fact that hemoglobin, hematocrit, erythrocytes, and ferritin all change after bloodletting is equally expected.

- Mild adverse effects are also no surprise.

- What is a surprise, however, that such a trial was ever conducted and passed by an ethics committee. Any medic who has not slept through his/her cardiovascular physiology lectures could have predicted the results quite accurately. And running a trial where the result is well-known before the study has started can hardly be called ethical.

As promised, I would like to correct the errors in my previous assessment of this paper. To remind everyone:

This systematic review evaluated individualized homeopathy as a treatment for children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) when compared to placebo or usual care alone.

Thirty-seven online sources were searched up to March 2021. Studies investigating the effects of individualized homeopathy against any control in ADHD were eligible. Data were extracted to a predefined excel sheet independently by two reviewers.

Six studies were analyzed:

- 5 were RCTs

- 2 were controlled against standard treatments;

- 4 were placebo-controlled and double-blinded.

The meta-analysis revealed a significant effect size across studies of Hedges’ g = 0.542 (95% CI 0.311-0.772; z = 4,61; p < 0.001) against any control and of g = 0.605 (95% CI 0.05-1.16; z = 2.16, p = 0.03) against placebo. The effect estimations are based on studies with an average sample size of 52 participants.

The authors concluded that individualized homeopathy showed a clinically relevant and statistically robust effect in the treatment of ADHD.

_______________________________

Now that I was able to access the full papers, I would like to offer a thorough analysis.

To get included in the review, primary studies had to be:

- Published after 1980,

- Investigating an individualized homeopathic intervention in childhood ADHD,

- Comparing the intervention to a control condition (placebo, standard care or treatment as usual, both of which are referred to as “active control”) in a randomized or non-randomized parallel-group study

design with one or more arms.

Six studies were included:

- Fibert, P., Peasgood, T. & Relton, C. Rethinking ADHD intervention trials: feasibility testing of two treatments and a methodology. Eur. J. Pediatr. 178, 983–993 (2019). – DOI

- Fibert, P., Relton, C., Heirs, M. & Bowden, D. A comparative consecutive case series of 20 children with a diagnosis of ADHD receiving homeopathic treatment, compared with 10 children receiving usual care. Homeopathy 105, 194–201 (2016). – DOI

- Jacobs, J., Williams, A. L., Girard, C., Njike, V. Y. & Katz, D. Homeopathy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot randomized-controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 11, 799–806 (2005). – DOI

- Jones, M. The efficacy of homoeopathic simillimum in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) in schoolgoing children aged 6-11 years. https://openscholar.dut.ac.za/bitstream/10321/534/1/Jones_2009.pdf (2009).

- Frei, H. et al. Homeopathic treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial. Eur. J. Pediatr. 164, 758–767 (2005). – DOI

- Oberai, P. et al. Homoeopathic management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomised placebo-controlled pilot trial. Indian J. Res. Homoeopathy 7, 158–167 (2013).

Exclusion criteria were:

- Homeopathic intervention not individualized,

- Serious methodological flaws, such as incidental unblinding, failure to report important data, or insufficient data for meta-analysis.

One study was excluded:

- Lamont, J. Homoeopathic treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br. Homeopathic J. 86, 196–200 (1997). – DOI

I will first make several points about Walach’s systematic review itself and then have a look at the primary studies that it included. Finally, I will try to draw some conclusions.

The review authors state in their introduction that “beneficial effects of this intervention [homeopathy] have been shown for various kinds of medical conditions, including child diarrhea, supportive care in cancer, fibromyalgia, or ADHD.” In other words, already in the introduction, they disclose their strong pro-homeopathy bias; it would, of course, not be difficult to find investigations that contradict their optimism.

Despite the stated inclusion/exclusion criteria, the authors did include the Frei-study that did not follow a parallel-group design (see also below).

The authors included two active-controlled studies both of which did not report the type of treatment received by the control group. In other words, these trials failed to report important data which was a stated exclusion criterium (see below).

In their discussion section, the authors state that “all included studies employed individualized homeopathy and were of comparable, solid quality, hence a lack of methodological rigor is unlikely the reason for the difference between homeopathy and controls…” This, I think, is grossly misleading; even according to the authors’ own assessments, one study was deemed to have a high risk of bias and in two studies the risk of bias was “unclear”.

The overall positive effect of homeopathy demonstrated by the review was determined almost exclusively by the study of Oberai et al (p-value = 0.000). In fact, the studies by Jones and by Jacobs were negative, and the one by Frei was borderline positive with a p-value of 0.46. The authors address this crucial issue repeatedly and claim that excluding Oberai et al would still generate an overall positive meta-analytic result. Yet, they do not mention that the overall result would no longer be clinically relevant.

Looking at the included primary studies, I should make the following points:

- The two Filbert studies, as mentioned, failed to report important data and should, according to the stated exclusion criteria, not have been included.

- The study by Jacobs was a pilot study and generated negative findings.

- The study by Jones is a non-peer-reviewed thesis. In my view, it should never have been included.

- The study by Frei was a cross-over trial. According to the exclusion/inclusion criteria of the authors, it should not have been included.

- The study by Oberai et al is the trial that has by far the largest effect size and thus is the driver of the overall result of the review. It is therefore important to have a closer look at it.

Here is the abstract:

Objective: To evaluate the usefulness of individualised homoeopathic medicines in treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Design: Randomised placebo-controlled single-blind pilot trial.

Setting: Central Research Institute (Homoeopathy), Kottayam, Kerala, India from June 2009 to November 2011.

Participants: Children aged 6-15 years meeting the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) criteria for ADHD.

Interventions: A total of 61 patients (Homoeopathy = 30, placebo = 31) were randomised to receive either individualised homoeopathic medicine in fifty millesimal (LM) potency or placebo for a period of one year.

Outcome measures: Conner’s Parent Rating Scale-Revised: Short (CPRS-R (S)), Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale (CGI-SS), Clinical Global Impression- Improvement Scale (CGI-IS) and Academic performance.

Results: A total of 54 patients (homoeopathy = 27, placebo = 27) were analysed under modified intention to treat (ITT). All patients in homoeopathy group showed better outcome in baseline adjusted General Linear Model (GLM) repeated measures ANCOVA for oppositional, cognition problems, hyperactivity and ADHD Index (domains of CPRS-R (S)) and CGI-IS at T3, T6, T9 and T12 (P = 0.0001). The mean baseline-adjusted treatment difference between groups at month 12 from baseline for all individual outcome measures favoured homoeopathy group; Oppositional (−16.4, 95% CI – 20.5 to − 12.2, P = 0.0001), Cognition problems (−15.5, 95% CI − 19.2 to − 11.8, P = 0.0001), Hyperactivity (−20.6, 95% CI − 25.6 to − 15.4, P = 0.0001), ADHD I (−15.6, 95% CI − 19.5 to − 11.6, P = 0.0001), Academic performance 14.4%, 95% CI 8.3 to 20.5, P = 0.0001), CGISS (−1.6, 95% CI − 1.9 to − 1.2, P = 0.0001), CGIIS (−1.6, 95% CI − 2.3 to -0.9, P = 0.0001).

Conclusion: This pilot study provides evidence to support the therapeutic effects of individualised homoeopathic medicines in ADHD children. However, the results need to be validated in multi-center randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Here are a few points of concern related to the Oberai et al:

- The trial was a mere pilot study.

- Despite the fact that it is now 9 years old, the authors never published a definitive trial.

- The study was published in an obscure journal that is not Medline-listed.

- The study is very poorly reported.

- It is unclear how the diagnosis of ADHD for including the patients was verified.

- The control patients were treated for one year with a placebo and no other therapies. In my view, this is not ethical.

- The method of randomization is unclear.

- The authors state that acute symptoms were treated throughout the study period with homeopathy, even in the control group. This seems odd and defies the principle of a placebo-controlled trial.

- The authors state that only the patients were blind, not the investigators. This opens the door wide for all sorts of biases. It is, for example, likely that it also de-blinded the patients (the verum could be adjusted and changed, while the placebo remained constant).

All in all, this paper is of poor quality, Its findings are far from trustworthy and were not meant to be definitive. According to the following exclusion criteria, it should have been excluded:

- It had several serious methodological flaws.

- It did not blind the investigators.

- It is likely that patients were de-blinded.

- It failed to report important data.

So, why did Walach and his co-authors include it?

Could it be because, without the Oberai-study, the overall findings of the review would at best have turned out to be borderline significant and not clinically relevant?

This systematic review evaluated individualized homeopathy as a treatment for children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) when compared to placebo or usual care alone.

Thirty-seven online sources were searched up to March 2021. Studies investigating the effects of individualized homeopathy against any control in ADHD were eligible. Data were extracted to a predefined excel sheet independently by two reviewers.

Six studies were analyzed:

- 5 were RCTs

- 2 were controlled against standard treatments;

- 4 were placebo-controlled and double-blinded.

The meta-analysis revealed a significant effect size across studies of Hedges’ g = 0.542 (95% CI 0.311-0.772; z = 4,61; p < 0.001) against any control and of g = 0.605 (95% CI 0.05-1.16; z = 2.16, p = 0.03) against placebo. The effect estimations are based on studies with an average sample size of 52 participants.

The authors concluded that individualized homeopathy showed a clinically relevant and statistically robust effect in the treatment of ADHD.

This is a counter-intuitive result (to put it mildly), and it is, therefore, wise to have a look at the 6 included studies:

1.Frei, H. et al. Homeopathic treatment of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial. Eur. J. Pediatr. 164, 758–767 (2005).

This was a trial with just 62 patients who had previously responded to homeopathy. The study was conducted by known proponents of homeopathy and had a highly unusual design. The results suggested that homeopathy was better than placebo.

2. Oberai, P. et al. Homoeopathic management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomised placebo-controlled pilot trial. Indian J. Res. Homoeopathy 7, 158–167 (2013).

This one was published in an obscure journal that I could not access.

3. Jacobs, J., Williams, A. L., Girard, C., Njike, V. Y. & Katz, D. Homeopathy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pilot randomized-controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 11, 799–806 (2005)

This study showed that there were no statistically significant differences between homeopathic remedy and placebo groups on the primary or secondary outcome variables.

4. Jones, M. The efficacy of homoeopathic simillimum in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) in schoolgoing children aged 6-11 years (2009).

This was a small unpublished (and not peer-reviewed) thesis. Its results showed no statistically significant effect of treatment.

5. Lamont, J. Homoeopathic treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br. Homeopathic J. 86, 196–200 (1997)

This was a small (n=46) trial with an unusual design. Its results suggested that homeopathy was better than placebo.

6. von Ammon, K. et al. Homeopathic RCT embedded in a long-term observational study of children with ADHD—a successful model of whole systems CAM research. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 1, 27 (2008).

Even though the journal is Medline-listed, I was unable to find this paper. I did, however, find a paper by the same authors with the same title. It turned out to be a duplication of the paper by Frei et al listed above.

_________________________

All in all, this brief analysis of the available abstracts (most full papers are behind paywalls) leaves many questions as to the trustworthiness of this systematic review unanswered. The fact that H. Walach (and other apologists of homeopathy) is its senior author does not inspire me with overwhelming confidence. In any case, I very much doubt that the authors’ conclusion is correct. I therefore would encourage someone with access to all full papers to initiate a more thorough analysis; the abstracts obviously leave many questions unanswered. For instance, it would be crucial to know how many of the trials followed an A+B versus B design (I suspect most studies did, and this would completely invalidate the review’s conclusion). I am more than happy to co-operate with such an evaluation.