clinical trial

Our ‘Memorandum Integrative Medicine‘ seems to be causing ripples. A German website that claims to aim at informing consumers objectively posted a rebuttal. Here is my translation (together with comments by myself inserted via reference numbers in brackets and added below):

With drastic words and narrow-mindedness bordering on ideology (1), the Münster Circle, an association of opponents to complementary therapies such as homeopathy (2), takes issue with the treatment concept of integrative medicine in a memorandum (3). By integrative medicine physicians understand the combination of doctor-led medicine and doctor-led complementary medicine to a meaningful total concept with the goal of reducing side effects and to treating patients individually and optimally (4). Integrative medicine focuses primarily on chronic diseases, where conventional acute medicine often reaches its limits (5)In the memorandum of the Münsteraner Kreis, general practitioner Dr. Claudia Novak criticizes integrative medicine as “guru-like self-dramatization” (6) by physicians and therapists, which undermines evidence-based medicine and leads to a deterioration in patient care. She is joined by Prof. Dr. Edzard Ernst, Professor Emeritus of Alternative Medicine, who has changed from Paul to Saul with regard to homeopathy (7) and is leading a veritable media campaign against proponents of treatment procedures that have not been able to prove their evidence in randomized placebo-controlled studies (8). The professor ignores the fact that this involves a large number of drugs that are used as a matter of course in everyday medicine (9) – for example, beta-blockers or other cardiological drugs (10). “Like the devil fears the holy water” (11), the Münsteraner Kreis seems to fear the concept of integrative medicine (12). The vehemence coupled with fear with which they warn against the treatment concept makes one sit up and take notice (13). “As an experienced gynecologist who has successfully worked with biological medicine as an adjunct in his practice for decades, I can only shake my head at such narrow-mindedness”, points out Fred-Holger Ludwig, MD (14). Science does not set limits for itself, but the plurality of methods is immanent (15). “Why doesn’t Prof. Ernst actually give up his professorial title for alternative medicine? That would have to be the logical consequence of its overloud criticism of established treatment concepts from homeopathy to to integrative medicine”, questions Dr. Ludwig (16).

The concept of integrative medicine is about infiltrating alternative procedures into medicine, claim the critics of the concept, without mentioning that many naturopathic procedures have been used for centuries with good results (17) and that healthcare research gives them top marks (18). “Incidentally, the scientists among the representatives of the Münster Circle should know that it is difficult to capture individualized treatment concepts with the standardized procedures of randomized, placebo-controlled studies (19). Anyone who declares the highest level of evidence to be the criterion for approval makes medicine impossible and deprives patients in oncology or with rare diseases, for example, of chances of successful treatment (20). Even there, drugs are used that cannot be based on high evidence, tested in placebo-controlled studies, because the number of cases is too low (21),” notes Dr. Ludwig .

- Ideology? Evidence is not ideology, in my view.

- We are an association of multidisciplinary experts advocating a level playing field with sound evidence in all areas of healthcare.

- The actual memorandum is not linked in this text; does the author not want his readers to form the own opinion?

- In our memorandum, we offer various definitions of integrative medicine (IM), none of which is remotely similar to this one.

- No, IM is usually being promoted in a much wider sense.

- This term does not appear in our memorandum.

- I am not aware that I changed from Paul to Saul with regard to homeopathy; I know that I was led mostly by the evidence.

- I feel flattered but don’t think that my humble work is a ‘media campaign’.

- True, I do not pretend to understand all areas of medicine and tend to be silent in the ones that I lack up-to-date expertise.

- Is he really saying that beta-blockers are not evidence-based?

- The holy water comparison from a homeopath, who arguably makes a living from dishing out ‘holy water’, made me laugh!

- It is most revealing, I think, that he thinks our motivation is fear.

- Splendid!

- FHL is the author of the article, and it is thus charmingly naive that he cites himself in this way

- I somehow doubt that he understands what he is expressing here.

- I find this rather a bizarre idea but I’ll think about it.

- Argumentum ad traditionem.

- Those that get ‘top marks’ belong to evidence-based medicine and not to IM.

- Here the author reveals that he does not understand the RCT methodology and even fails to know the trial evidence on homeopathy – RCTs of individualised homeopathy are possible and have been published (e.g. this one).

- If he really believes this, I fear for his patients.

- Pity that he does not provide an example.

To understand FHL better, it is worth knowing that he claims to treat cancer patients with conventional and homeopathic medicine. He states that this approach reduces side effects – without providing evidence, of course.

Altogether, FHL does not dispute a single fact or argument from our memorandum. In fact, I get the impression that he never actually read it. To me, it feels as though he merely read an article ABOUT the document. In any case, his critique is revealing and important, in my view. It demonstrates that there are no good arguments to defend IM.

So, thank you FHL!

Didier Raoult, the French scientist who became well-known for his controversial stance on hydroxychloroquine for treating COVID-19, has featured on this blog before (see here, here, and here). Less well-known is the fact that he has attracted controversy before. In 2006, Raoult and 4 co-authors were banned for one year from publishing in the journals of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM), after a reviewer for Infection and Immunity discovered that four figures from the revised manuscript of a paper about a mouse model for typhus were identical to figures from the originally submitted manuscript, even though they were supposed to represent a different experiment. In response, Raoult “resigned from the editorial board of two other ASM journals, canceled his membership in the American Academy of Microbiology, ASM’s honorific leadership group, and banned his lab from submitting to ASM journals”. In response to Science covering the story in 2012, he stated that, “I did not manage the paper and did not even check the last version”. The paper was subsequently published in a different journal.

Now, the publisher PLOS is marking nearly 50 articles by Didier Raoult, with expressions of concern while it investigates potential research ethics violations in the work. PLOS has been looking into more than 100 articles by Raoult and determined that the issues in 49 of the papers, including reuse of ethics approval reference numbers, warrant expressions of concern while the publisher continues its inquiry.

In August of 2021, Elisabeth Bik wrote on her blog about a series of 17 articles from IHU-Méditerranée Infection that described different studies involving homeless people in Marseille over a decade, but all listed the same institutional ethics approval number. Bik and other commenters on PubPeer have identified ethical concerns in many other papers, including others in large groups of papers with the same ethical approval numbers. Subsequently, Bik has received harassment and legal threats from Raoult.

David Knutson, senior manager of communications for PLOS, sent ‘Retraction Watch’ this statement:

PLOS is issuing interim Expressions of Concerns for 49 articles that are linked to researchers affiliated with IHU-Méditerranée Infection (Marseille, France) and/or the Aix-Marseille University, as part of an ongoing case that involves more than 100 articles in total. Many of the papers in this case include controversial scientist Didier Raoult as a co-author.

Several whistleblowers raised concerns about articles from this institute, including that several ethics approval reference numbers have been reused in many articles. Our investigation, which has been ongoing for more than a year, confirmed ethics approval reuse and also uncovered other issues including:

- highly prolific authorship (a rate that would equate to nearly 1 article every 3 days for one or more individuals), which calls into question whether PLOS’ authorship criteria have been met

- undeclared COIs with pharmaceutical companies

To date, PLOS has completed a detailed initial assessment of 108 articles in total and concluded that 49 warrant an interim Expression of Concern due to the nature of the concerns identified. We’ll be following up with the authors of all articles of concern in accordance with COPE guidance and PLOS policies, but we anticipate it will require at least another year to complete this work.

Raoult is a coauthor on 48 of the 49 papers in question. This summer, Raoult retired as director of IHU-Méditerranée Infection, the hospital and research institution in Marseille that he had overseen since 2011, following an inspection by the French National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM) that found “serious shortcomings and non-compliances with the regulations for research involving the human person” at IHU-Méditerranée Infection and another Marseille hospital. ANSM imposed sanctions on IHU-Méditerranée Infection, including suspending a research study and placing any new research involving people under supervision, and called for a criminal investigation. Other regulators have also urged Marseille’s prosecutor to investigate “serious malfunctions” at the research institution.

Pierre-Edouard Fournier, the new director of IHU-Méditerranée Infection, issued a statement on September 7th that said he had “ensured that all clinical trials in progress relating to research involving the human person (RIPH) were suspended pending the regularization of the situation.” Also in September, the American Society for Microbiology placed expressions of concern on 6 of Raoult’s papers in two of its journals, citing “a ‘scientific misconduct investigation’ by the University of Aix Marseille,” where the researcher also has an affiliation.

___________________________

Christian Lehman predicted on my blog that ” If Covid19 settles in the long-term, he [Raoult] will not be able to escape a minutely detailed autopsy of his statements and his actions. And the result will be devastating.” It seems he was correct.

Is acupuncture more than a theatrical placebo? Acupuncture fans are convinced that the answer to this question is YES. Perhaps this paper will make them think again.

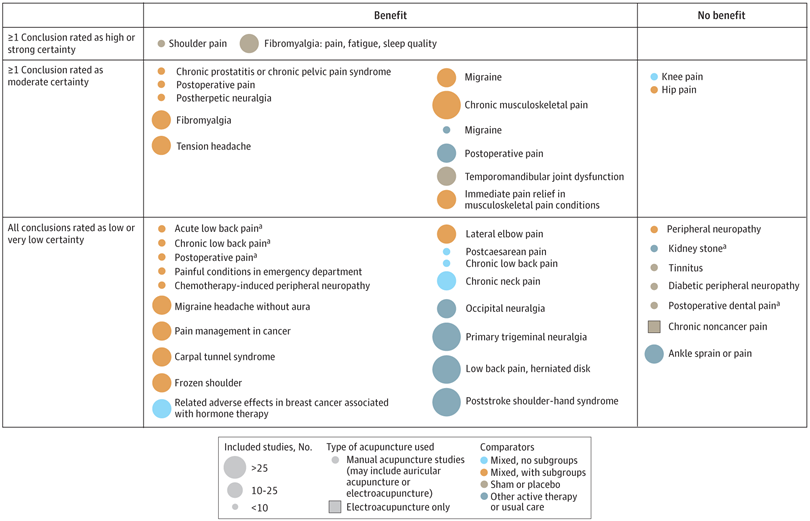

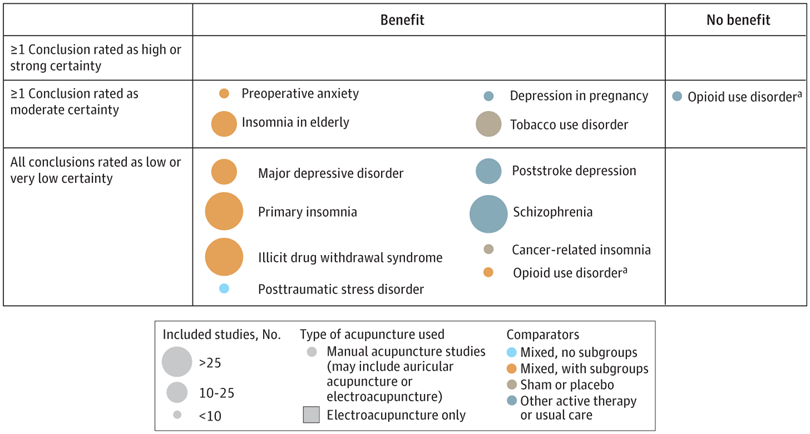

A new analysis mapped the systematic reviews, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence for outcomes of acupuncture as a treatment for adult health conditions. Computerized search of PubMed and 4 other databases from 2013 to 2021. Systematic reviews of acupuncture (whole body, auricular, or electroacupuncture) for adult health conditions that formally rated the certainty, quality, or strength of evidence for conclusions. Studies of acupressure, fire acupuncture, laser acupuncture, or traditional Chinese medicine without mention of acupuncture were excluded. Health condition, number of included studies, type of acupuncture, type of comparison group, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence. Reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as high-certainty evidence, reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as moderate-certainty evidence and reviews with all conclusions rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence; full list of all conclusions and certainty of evidence.

A total of 434 systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions were found; of these, 127 reviews used a formal method to rate the certainty or quality of evidence of their conclusions, and 82 reviews were mapped, covering 56 health conditions. Across these, there were 4 conclusions that were rated as high-certainty evidence and 31 conclusions that were rated as moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions (>60) were rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence. Approximately 10% of conclusions rated as high or moderate-certainty were that acupuncture was no better than the comparator treatment, and approximately 75% of high- or moderate-certainty evidence conclusions were about acupuncture compared with a sham or no treatment.

Three evidence maps (pain, mental conditions, and other conditions) are shown below

The authors concluded that despite a vast number of randomized trials, systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions have rated only a minority of conclusions as high- or moderate-certainty evidence, and most of these were about comparisons with sham treatment or had conclusions of no benefit of acupuncture. Conclusions with moderate or high-certainty evidence that acupuncture is superior to other active therapies were rare.

These findings are sobering for those who had hoped that acupuncture might be effective for a range of conditions. Despite the fact that, during recent years, there have been numerous systematic reviews, the evidence remains negative or flimsy. As 34 reviews originate from China, and as we know about the notorious unreliability of Chinese acupuncture research, this overall result is probably even more negative than the authors make it out to be.

Considering such findings, some people (including the authors of this analysis) feel that we now need more and better acupuncture trials. Yet I wonder whether this is the right approach. Would it not be better to call it a day, concede that acupuncture generates no or only relatively minor effects, and focus our efforts on more promising subjects?

Today, you cannot read a newspaper or listen to the radio without learning that there has been a significant, sensational, momentous, unprecedented, etc. breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The reason for all this excitement (or is it hype?) is this study just out in the NEJM:

BACKGROUND

The accumulation of soluble and insoluble aggregated amyloid-beta (Aβ) may initiate or potentiate pathologic processes in Alzheimer’s disease. Lecanemab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to Aβ soluble protofibrils, is being tested in persons with early Alzheimer’s disease.

METHODS

We conducted an 18-month, multicenter, double-blind, phase 3 trial involving persons 50 to 90 years of age with early Alzheimer’s disease (mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease) with evidence of amyloid on positron-emission tomography (PET) or by cerebrospinal fluid testing. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive intravenous lecanemab (10 mg per kilogram of body weight every 2 weeks) or placebo. The primary end point was the change from baseline at 18 months in the score on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB; range, 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating greater impairment). Key secondary end points were the change in amyloid burden on PET, the score on the 14-item cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog14; range, 0 to 90; higher scores indicate greater impairment), the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (ADCOMS; range, 0 to 1.97; higher scores indicate greater impairment), and the score on the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment (ADCS-MCI-ADL; range, 0 to 53; lower scores indicate greater impairment).

RESULTS

A total of 1795 participants were enrolled, with 898 assigned to receive lecanemab and 897 to receive placebo. The mean CDR-SB score at baseline was approximately 3.2 in both groups. The adjusted least-squares mean change from baseline at 18 months was 1.21 with lecanemab and 1.66 with placebo (difference, −0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.67 to −0.23; P<0.001). In a substudy involving 698 participants, there were greater reductions in brain amyloid burden with lecanemab than with placebo (difference, −59.1 centiloids; 95% CI, −62.6 to −55.6). Other mean differences between the two groups in the change from baseline favoring lecanemab were as follows: for the ADAS-cog14 score, −1.44 (95% CI, −2.27 to −0.61; P<0.001); for the ADCOMS, −0.050 (95% CI, −0.074 to −0.027; P<0.001); and for the ADCS-MCI-ADL score, 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2 to 2.8; P<0.001). Lecanemab resulted in infusion-related reactions in 26.4% of the participants and amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema or effusions in 12.6%.

CONCLUSIONS

Lecanemab reduced markers of amyloid in early Alzheimer’s disease and resulted in moderately less decline on measures of cognition and function than placebo at 18 months but was associated with adverse events. Longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. (Funded by Eisai and Biogen; Clarity AD ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03887455. opens in new tab.)

It’s a good study, and I (like everyone else) hope that it will mean tangible progress in the management of that devastating disease. Most media outlets are announcing the news with the claim that it is the FIRST TIME that any treatment has been shown to delay the cognitive decline of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

But is this true?

I think not!

There have been several studies showing that the herbal remedy GINKGO BILOBA slows the Alzheimer-related decline. Here is the latest systematic review of the subject:

Background: Ginkgo biloba is a natural medicine used for cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. The objective of this review is to explore the effectiveness and safety of Ginkgo biloba in treating mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods: Electronic search was conducted from PubMed, Cochrane Library, and four major Chinese databases from their inception up to 1(st) December, 2014 for randomized clinical trials on Ginkgo biloba in treating mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. Meta-analyses were performed by RevMan 5.2 software.

Results: 21 trials with 2608 patients met the inclusion criteria. The general methodological quality of included trials was moderate to poor. Compared with conventional medicine alone, Ginkgo biboba in combination with conventional medicine was superior in improving Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores at 24 weeks for patients with Alzheimer’s disease (MD 2.39, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.50, P<0.0001) and mild cognitive impairment (MD 1.90, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.39, P<0.00001), and Activity of Daily Living (ADL) scores at 24 weeks for Alzheimer’s disease (MD -3.72, 95% CI -5.68 to -1.76, P=0.0002). When compared with placebo or conventional medicine in individual trials, Ginkgo biboba demonstrated similar but inconsistent findings. Adverse events were mild.

Conclusion: Ginkgo biloba is potentially beneficial for the improvement of cognitive function, activities of daily living, and global clinical assessment in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. However, due to limited sample size, inconsistent findings and methodological quality of included trials, more research are warranted to confirm the effectiveness and safety of ginkgo biloba in treating mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease.

I know, the science is not nearly as good as that of the NEJM trial. I also know that the trial data for ginkgo biloba are not uniformly positive. And I know that, after several studies showed good results, later trials tended not to confirm them.

But this is what very often happens in clinical research: studies are initially promising, only to be disappointing as more studies emerge. I sincerely hope that this will not happen with the new drug ‘Lecanemab’ and that today’s excitement will not turn out to be hype.

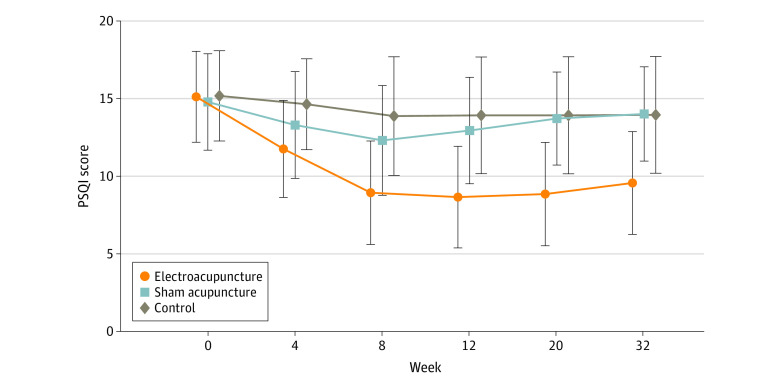

Electroacupuncture (EA) is often advocated for depression and sleep disorders but its efficacy remains uncertain. The aim of this study was, therefore, to “assess the efficacy and safety of EA as an alternative therapy in improving sleep quality and mental state for patients with insomnia and depression.”

A 32-week patient- and assessor-blinded, randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial (8-week intervention plus 24-week follow-up) was conducted from September 1, 2016, to July 30, 2019, at 3 tertiary hospitals in Shanghai, China. Patients were randomized to receive

- EA treatment and standard care,

- sham acupuncture (SA) treatment and standard care,

- standard care only as control.

Patients in the EA or SA groups received a 30-minute treatment 3 times per week (usually every other day except Sunday) for 8 consecutive weeks. All treatments were performed by licensed acupuncturists with at least 5 years of clinical experience. A total of 6 acupuncturists (2 at each center; including X.Y. and S.Z.) performed EA and SA, and they received standardized training on the intervention method before the trial. The regular acupuncture method was applied at the Baihui (GV20), Shenting (GV24), Yintang (GV29), Anmian (EX-HN22), Shenmen (HT7), Neiguan (PC6), and SanYinjiao (SP6) acupuncture points, with 0.25 × 25-mm and 0.30 × 40-mm real needles (Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd), or 0.30 × 30-mm sham needles (Streitberger sham device [Asia-med GmbH]).

For patients in the EA group, rotating or lifting-thrusting manipulation was applied for deqi sensation after needle insertion. The 2 electrodes of the electrostimulator (CMNS6-1 [Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd]) were connected to the needles at GV20 and GV29, delivering a continuous wave based on the patient’s tolerance. Patients in the SA group felt a pricking sensation when the blunt needle tip touched the skin, but without needle insertion. All indicators of the nearby electrostimulator were set to 0, with the light switched on. Standard care (also known as treatment as usual or routine care) was used in the control group. Patients receiving standard care were recommended by the researchers to get regular exercise, eat a healthy diet, and manage their stress level during the trial. They were asked to keep the regular administration of antidepressants, sedatives, or hypnotics as well. Psychiatrists in the Shanghai Mental Health Center (including X.L.) guided all patients’ standard care treatment and provided professional advice when a patient’s condition changed.

The primary outcome was change in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) from baseline to week 8. Secondary outcomes included PSQI at 12, 20, and 32 weeks of follow-up; sleep parameters recorded in actigraphy; Insomnia Severity Index; 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score; and Self-rating Anxiety Scale score.

Among the 270 patients (194 women [71.9%] and 76 men [28.1%]; mean [SD] age, 50.3 [14.2] years) included in the intention-to-treat analysis, 247 (91.5%) completed all outcome measurements at week 32, and 23 (8.5%) dropped out of the trial. The mean difference in PSQI from baseline to week 8 within the EA group was -6.2 (95% CI, -6.9 to -5.6). At week 8, the difference in PSQI score was -3.6 (95% CI, -4.4 to -2.8; P < .001) between the EA and SA groups and -5.1 (95% CI, -6.0 to -4.2; P < .001) between the EA and control groups. The efficacy of EA in treating insomnia was sustained during the 24-week postintervention follow-up. Significant improvement in the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (-10.7 [95% CI, -11.8 to -9.7]), Insomnia Severity Index (-7.6 [95% CI, -8.5 to -6.7]), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (-2.9 [95% CI, -4.1 to -1.7]) scores and the total sleep time recorded in the actigraphy (29.1 [95% CI, 21.5-36.7] minutes) was observed in the EA group during the 8-week intervention period (P < .001 for all). No between-group differences were found in the frequency of sleep awakenings. No serious adverse events were reported.

The result of the blinding assessment showed that 56 patients (62.2%) in the SA group guessed wrongly about their group assignment (Bang blinding index, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.3]), whereas 15 (16.7%) in the EA group also guessed wrongly (Bang blinding index, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.4-0.7]). This indicated a relatively higher degree of blinding in the SA group.

The authors concluded that, in this randomized clinical trial of EA treatment for insomnia in patients with depression, quality of sleep improved significantly in the EA group compared with the SA or control group at week 8 and was sustained at week 32.

This trial seems rigorous, it has a sizable sample size, uses a credible placebo procedure, and is reported in sufficient detail. Why then am I skeptical?

- Perhaps because we have often discussed how untrustworthy acupuncture studies from China are?

- Perhaps because I fail to see a plausible mechanism of action?

- Perhaps because the acupuncturists could not be blinded and thus might have influenced the outcome?

- Perhaps because the effects of sham acupuncture seem unreasonably small?

- Perhaps because I cannot be sure whether the acupuncture or the electrical current is supposed to have caused the effects?

- Perhaps because the authors of the study are from institutions such as the Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Huadong Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai,

- Perhaps because the results seem too good to be true?

If you have other and better reasons, I’d be most interested to hear them.

This double-blind, randomized study assessed the effectiveness of physiotherapy instrument mobilization (PIM) in patients with low back pain (LBP) and compared it with the effectiveness of manual mobilization.

Thirty-two participants with LBP were randomly assigned to one of two groups:

- The PIM group received lumbar mobilization using an activator instrument, stabilization exercises, and education.

- The manual group received lumbar mobilization using a pisiform grip, stabilization exercises, and education.

Both groups had 4 treatment sessions over 2-3 weeks. The following outcomes were measured before the intervention, and after the first and fourth sessions:

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS),

- Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scale,

- Pressure pain threshold (PPT),

- lumbar spine range of motion (ROM),

- lumbar multifidus muscle activation.

There were no differences between the PIM and manual groups in any outcome measures. However, over the period of study, there were improvements in both groups in NPRS (PIM: 3.23, Manual: 3.64 points), ODI (PIM: 17.34%, Manual: 14.23%), PPT (PIM: ⩽ 1.25, Manual: ⩽ 0.85 kg.cm2), lumbar spine ROM (PIM: ⩽ 9.49∘, Manual: ⩽ 0.88∘), and/or lumbar multifidus muscle activation (percentage thickness change: PIM: ⩽ 4.71, Manual: ⩽ 4.74 cm; activation ratio: PIM: ⩽ 1.17, Manual: ⩽ 1.15 cm).

The authors concluded that both methods of lumbar spine mobilization demonstrated comparable improvements in pain and disability in patients with LBP, with neither method exhibiting superiority over the other.

If this conclusion is meant to tell us that both treatments were equally effective, I beg to differ. The improvements documented here are consistent with improvements caused by the natural history of the condition, regression towards the mean, and placebo effects. The data do not prove that they are due to the treatments. On the contrary, they seem to imply that patients get better no matter what therapy is used. Thus, I feel that the results are entirely in keeping with the hypothesis that spinal mobilization is a placebo treatment.

So, allow me to re-phrase the authors’ conclusion as follows:

Lumbar mobilizations do not seem to have specific therapeutic effects and might therefore be considered to be ineffective for LBP.

Acupuncture is emerging as a potential therapy for relieving pain, but the effectiveness of acupuncture for relieving low back and/or pelvic pain (LBPP) during pregnancy remains controversial. This meta-analysis aimed to investigate the effects of acupuncture on pain, functional status, and quality of life for women with LBPP pain during pregnancy.

The authors included all RCTs evaluating the effects of acupuncture on LBPP during pregnancy. Data extraction and study quality assessments were independently performed by three reviewers. The mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs for pooled data were calculated. The primary outcomes were pain, functional status, and quality of life. The secondary outcomes were overall effects (a questionnaire at a post-treatment visit within a week after the last treatment to determine the number of people who received good or excellent help), analgesic consumption, Apgar scores >7 at 5 min, adverse events, gestational age at birth, induction of labor and mode of birth.

Ten studies, reporting on a total of 1040 women, were included. Overall, acupuncture

- relieved pain during pregnancy (MD=1.70, 95% CI: (0.95 to 2.45), p<0.00001, I2=90%),

- improved functional status (MD=12.44, 95% CI: (3.32 to 21.55), p=0.007, I2=94%),

- improved quality of life (MD=−8.89, 95% CI: (−11.90 to –5.88), p<0.00001, I2 = 57%).

There was a significant difference in overall effects (OR=0.13, 95% CI: (0.07 to 0.23), p<0.00001, I2 = 7%). However, there was no significant difference in analgesic consumption during the study period (OR=2.49, 95% CI: (0.08 to 80.25), p=0.61, I2=61%) and Apgar scores of newborns (OR=1.02, 95% CI: (0.37 to 2.83), p=0.97, I2 = 0%). Preterm birth from acupuncture during the study period was reported in two studies. Although preterm contractions were reported in two studies, all infants were in good health at birth. In terms of gestational age at birth, induction of labor, and mode of birth, only one study reported the gestational age at birth (mean gestation 40 weeks).

The authors concluded that acupuncture significantly improved pain, functional status and quality of life in women with LBPP during the pregnancy. Additionally, acupuncture had no observable severe adverse influences on the newborns. More large-scale and well-designed RCTs are still needed to further confirm these results.

What should we make of this paper?

In case you are in a hurry: NOT A LOT!

In case you need more, here are a few points:

- many trials were of poor quality;

- there was evidence of publication bias;

- there was considerable heterogeneity within the studies.

The most important issue is one studiously avoided in the paper: the treatment of the control groups. One has to dig deep into this paper to find that the control groups could be treated with “other treatments, no intervention, and placebo acupuncture”. Trials comparing acupuncture combined plus other treatments with other treatments were also considered to be eligible. In other words, the analyses included studies that compared acupuncture to no treatment at all as well as studies that followed the infamous ‘A+Bversus B’ design. Seven studies used no intervention or standard of care in the control group thus not controlling for placebo effects.

Nobody can thus be in the slightest surprised that the overall result of the meta-analysis was positive – false positive, that is! And the worst is that this glaring limitation was not discussed as a feature that prevents firm conclusions.

Dishonest researchers?

Biased reviewers?

Incompetent editors?

Truly unbelievable!!!

In consideration of these points, let me rephrase the conclusions:

The well-documented placebo (and other non-specific) effects of aacupuncture improved pain, functional status and quality of life in women with LBPP during the pregnancy. Unsurprisingly, acupuncture had no observable severe adverse influences on the newborns. More large-scale and well-designed RCTs are not needed to further confirm these results.

PS

I find it exasperating to see that more and more (formerly) reputable journals are misleading us with such rubbish!!!

The aim of this evaluator-blinded randomized clinical trial was to determine if manual therapy added to a therapeutic exercise program produced greater improvements than a sham manual therapy added to the same exercise program in patients with non-specific shoulder pain.

Forty-five subjects were randomly allocated into one of three groups:

- manual therapy (glenohumeral mobilization technique and rib-cage technique);

- thoracic sham manual therapy (glenohumeral mobilization technique and rib-cage sham technique);

- sham manual therapy (sham glenohumeral mobilization technique and rib-cage sham technique).

All groups also received a therapeutic exercise program. Pain intensity, disability, and pain-free active shoulder range of motion were measured post-treatment and at 4-week and 12-week follow-ups. Mixed-model analyses of variance and post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were constructed for the analysis of the outcome measures.

All groups reported improved pain intensity, disability, and pain-free active shoulder range of motion. However, there were no between-group differences in these outcome measures.

The authors concluded that the addition of the manual therapy techniques applied in the present study to a therapeutic exercise protocol did not seem to add benefits to the management of subjects with non-specific shoulder pain.

What does that mean?

I think it means that the improvements observed in this study were due to 1) exercise and 2) a range of non-specific effects, and that they were not due to the manual techniques tested.

I cannot say that I find this enormously surprising. But I would also find it unsurprising if fans of these methods would claim that the results show that the physios applied the techniques not correctly.

In any case, I feel this is an interesting study, not least because of its use of sham therapy. But I somehow doubt that the patients were unable to distinguish sham from verum. If so, the study was not patient-blind which obviously is difficult to achieve with manual treatments.

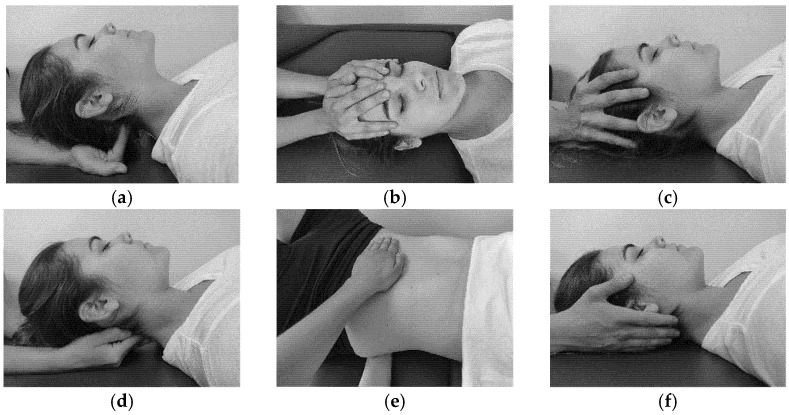

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of craniosacral therapy on different features in migraine patients.

Fifty individuals with migraine were randomly divided into two groups (n = 25 per group):

- craniosacral therapy group (CTG),

- sham control group (SCG).

The interventions were carried out with the patient in the supine position. The CTG received a manual therapy treatment focused on the craniosacral region including five techniques, and the SCG received a hands-on placebo intervention. After the intervention, individuals remained supine with a neutral neck and head position for 10 min, to relax and diminish tension after treatment. The techniques were executed by the same experienced physiotherapist in both groups.

The analyzed variables were pain, migraine severity, and frequency of episodes, functional, emotional, and overall disability, medication intake, and self-reported perceived changes, at baseline, after a 4-week intervention, and at an 8-week follow-up.

After the intervention, the CTG significantly reduced pain (p = 0.01), frequency of episodes (p = 0.001), functional (p = 0.001) and overall disability (p = 0.02), and medication intake (p = 0.01), as well as led to a significantly higher self-reported perception of change (p = 0.01), when compared to SCG. The results were maintained at follow-up evaluation in all variables.

The authors concluded that a protocol based on craniosacral therapy is effective in improving pain, frequency of episodes, functional and overall disability, and medication intake in migraineurs. This protocol may be considered as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients.

Sorry, but I disagree!

And I have several reasons for it:

- The study was far too small for such strong conclusions.

- For considering any treatment as a therapeutic approach in migraine patients, we would need at least one independent replication.

- There is no plausible rationale for craniosacral therapy to work for migraine.

- The blinding of patients was not checked, and it is likely that some patients knew what group they belonged to.

- There could have been a considerable influence of the non-blinded therapists on the outcomes.

- There was a near-total absence of a placebo response in the control group.

Altogether, the findings seem far too good to be true.

This study aimed to evaluate the number of craniosacral therapy sessions that can be helpful to obtain a resolution of the symptoms of infantile colic and to observe if there are any differences in the evolution obtained by the groups that received a different number of Craniosacral Therapy sessions at 24 days of treatment, compared with the control group which did not received any treatment.

Fifty-eight infants with colic were randomized into two groups:

- 29 babies in the control group received no treatment;

- babies in the experimental group received 1-3 sessions of craniosacral therapy (CST) until symptoms were resolved.

Evaluations were performed until day 24 of the study. Crying hours served as the primary outcome measure. The secondary outcome measures were the hours of sleep and the severity, measured by an Infantile Colic Severity Questionnaire (ICSQ).

Statistically significant differences were observed in favor of the experimental group compared to the control group on day 24 in all outcome measures:

- crying hours (mean difference = 2.94, at 95 %CI = 2.30-3.58; p < 0.001);

- hours of sleep (mean difference = 2.80; at 95 %CI = – 3.85 to – 1.73; p < 0.001);

- colic severity (mean difference = 17.24; at 95 %CI = 14.42-20.05; p < 0.001).

Also, the differences between the groups ≤ 2 CST sessions (n = 19), 3 CST sessions (n = 10), and control (n = 25) were statistically significant on day 24 of the treatment for crying, sleep and colic severity outcomes (p < 0.001).

The authors concluded that babies with infantile colic may obtain a complete resolution of symptoms on day 24 by receiving 2 or 3 CST sessions compared to the control group, which did not receive any treatment.

Why do SCAM researchers so often have no problem leaving the control group of patients in clinical trials without any treatment at all, while shying away from administering a placebo? Is it because they enjoy being the laughingstock of the science community? Probably not.

I suspect the reason might be that often they know that their treatments are placebos and that their trials would otherwise generate negative findings. Whatever the reasons, this new study demonstrates three things many of us already knew:

- Colic in babies always resolves on its own but can be helped by a placebo response (e.g. via the non-blinded parents), by holding the infant, and by paying attention to the child.

- Flawed trials lend themselves to drawing the wrong conclusions.

- Craniosacral therapy is not biologically plausible and most likely not effective beyond placebo.