Chinese studies

This pilot study tested the feasibility of using US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–recommended endpoints to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of IBS. It was designed as a multicenter randomized clinical trial, conducted in 4 tertiary hospitals in China from July 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021, and 14-week data collection was completed in March 2021. Individuals with a diagnosis of IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) were randomized to 1 of 3 groups:

- acupuncture groups 1 (using specific acupoints [SA])

- acupuncture group 2 (using nonspecific acupoints [NSA])

- sham acupuncture group (non-acupoints [NA])

Patients in all groups received twelve 30-minute sessions over 4 consecutive weeks at 3 sessions per week, ideally every other day.

The primary outcome was the response rate at week 4, which was defined as the proportion of patients whose worst abdominal pain score (score range, 0-10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating unbearable severe pain) decreased by at least 30% and the number of type 6 or 7 stool days decreased by 50% or greater.

Ninety patients (54 male [60.0%]; mean [SD] age, 34.5 [11.3] years) were enrolled, with 30 patients in each group. There were substantial improvements in the primary outcomes for all groups

- response rates in the SA group = 46.7% [95% CI, 28.8%-65.4%]

- response rate in the NSA group = 46.7% [95% CI, 28.8%-65.4%]

- response rate in the NA group = 26.7% [95% CI, 13.0%-46.2%]

The difference between the groups was not statistically significant (P = .18). The response rates of adequate relief at week 4 were 64.3% (95% CI, 44.1%-80.7%) in the SA group, 62.1% (95% CI, 42.4%-78.7%) in the NSA group, and 55.2% (95% CI, 36.0%-73.0%) in the NA group (P = .76). Adverse events were reported in 2 patients (6.7%) in the SA group and 3 patients (10%) in NSA or NA group.

The authors concluded that acupuncture in both the SA and NSA groups showed clinically meaningful improvement in IBS-D symptoms, although there were no significant differences among the 3 groups. These findings suggest that acupuncture is feasible and safe; a larger, sufficiently powered trial is needed to accurately assess efficacy.

WHAT A LOAD OF TOSH!

Here are some of the most obvious issues I have with this new study:

- A pilot study is not about reporting effectiveness/efficacy but about testing the feasibility of a study.

- That acupuncture is feasible has been known for ~2000 years.

- The conclusion that acupuncture is safe is not warranted on the basis of the data; for that we would need a much larger investigation.

- The authors seem to have used our sham needle without acknowledging it.

- The authors are affiliated with the International Acupuncture and Moxibustion Innovation Institute, School of Acupuncture-Moxibustion and Tuina, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, yet they state that they have no conflicts of interest.

- The results are clearly negative, yet the authors seem to attempt to draw a positive conclusion.

The main question that occurs to me is this: how low has the JAMA sunk to publish such junk?

Earlier this year, I started the ‘WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION’. As a prize, I am offering the winner (that is the lead author of the winning paper) one of my books that best fits his/her subject. I am sure this will overjoy him or her. I hope to identify about 10 candidates for the prize, and towards the end of the year, I let my readers decide democratically on who should be the winner. In this spirit of democratic voting, let me suggest to you entry No 9. Here is the unadulterated abstract:

Background

With the increasing popularity of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) by the global community, how to teach basic knowledge of TCM to international students and improve the teaching quality are important issues for teachers of TCM. The present study was to analyze the perceptions from both students and teachers on how to improve TCM learning internationally.

Methods

A cross-sectional national survey was conducted at 23 universities/colleges across China. A structured, self-reported on-line questionnaire was administered to 34 Chinese teachers who taught TCM course in English and to 1016 international undergraduates who were enrolled in the TCM course in China between 2017 and 2021.

Results

Thirty-three (97.1%) teachers and 900 (88.6%) undergraduates agreed Chinese culture should be fully integrated into TCM courses. All teachers and 944 (92.9%) undergraduates thought that TCM had important significance in the clinical practice. All teachers and 995 (97.9%) undergraduates agreed that modern research of TCM is valuable. Thirty-three (97.1%) teachers and 959 (94.4%) undergraduates thought comparing traditional medicine in different countries with TCM can help the students better understand TCM. Thirty-two (94.1%) teachers and 962 (94.7%) undergraduates agreed on the use of practical teaching method with case reports. From the perceptions of the undergraduates, the top three beneficial learning styles were practice (34.3%), teacher’s lectures (32.5%), case studies (10.4%). The first choice of learning mode was attending to face-to-face teaching (82.3%). The top three interesting contents were acupuncture (75.5%), Chinese herbal medicine (63.8%), and massage (55.0%).

Conclusion

To improve TCM learning among international undergraduates majoring in conventional medicine, integration of Chinese culture into TCM course, comparison of traditional medicine in different countries with TCM, application of the teaching method with case reports, and emphasization of clinical practice as well as modern research on TCM should be fully considered.

I am impressed with this paper mainly because to me it does not make any sense at all. To be blunt, I find it farcically nonsensical. What precisely? Everything:

- the research question,

- the methodology,

- the conclusion

- the write-up,

- the list of authors and their affiliations: Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Basic Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Medical College, China Three Gorges University, Yichang, China, Basic Teaching and Research Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China, Institute of Integrative Medicine, Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China, Department of Chinese and Western Medicine, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China, Department of Chinese Medicine/Department of Chinese Integrative Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shengjing Hospital Affiliated to China Medical University, Shenyang, China, Department of Acupuncture, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, Teaching and Research Section of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shengli Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medicine University, Jinzhou, China, Department of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, Department of Chinese Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China.

- the journal that had this paper peer-reviewed and published.

But what impressed me most with this paper is the way the authors managed to avoid even the slightest hint of critical thinking. They even included a short paragraph in the discussion section where they elaborate on the limitations of their work without ever discussing the true flaws in the conception and execution of this extraordinary example of pseudoscience.

Is acupuncture more than a theatrical placebo? Acupuncture fans are convinced that the answer to this question is YES. Perhaps this paper will make them think again.

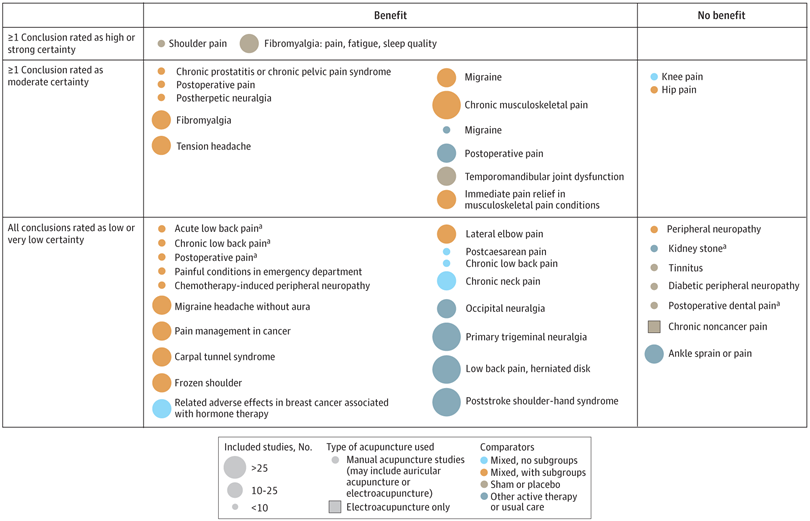

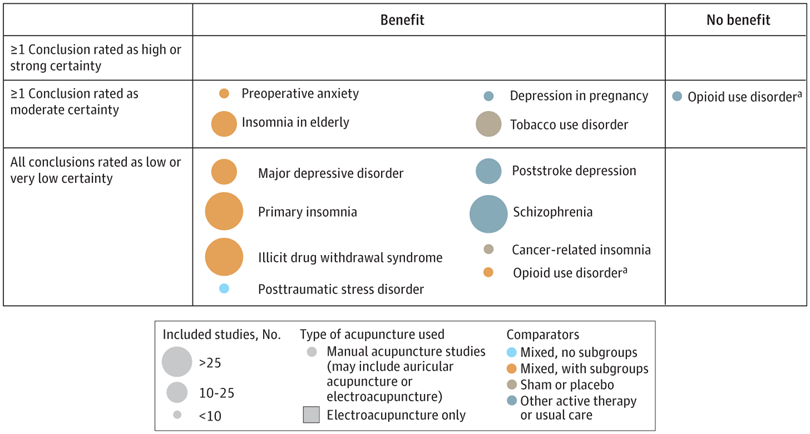

A new analysis mapped the systematic reviews, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence for outcomes of acupuncture as a treatment for adult health conditions. Computerized search of PubMed and 4 other databases from 2013 to 2021. Systematic reviews of acupuncture (whole body, auricular, or electroacupuncture) for adult health conditions that formally rated the certainty, quality, or strength of evidence for conclusions. Studies of acupressure, fire acupuncture, laser acupuncture, or traditional Chinese medicine without mention of acupuncture were excluded. Health condition, number of included studies, type of acupuncture, type of comparison group, conclusions, and certainty or quality of evidence. Reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as high-certainty evidence, reviews with at least 1 conclusion rated as moderate-certainty evidence and reviews with all conclusions rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence; full list of all conclusions and certainty of evidence.

A total of 434 systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions were found; of these, 127 reviews used a formal method to rate the certainty or quality of evidence of their conclusions, and 82 reviews were mapped, covering 56 health conditions. Across these, there were 4 conclusions that were rated as high-certainty evidence and 31 conclusions that were rated as moderate-certainty evidence. All remaining conclusions (>60) were rated as low- or very low-certainty evidence. Approximately 10% of conclusions rated as high or moderate-certainty were that acupuncture was no better than the comparator treatment, and approximately 75% of high- or moderate-certainty evidence conclusions were about acupuncture compared with a sham or no treatment.

Three evidence maps (pain, mental conditions, and other conditions) are shown below

The authors concluded that despite a vast number of randomized trials, systematic reviews of acupuncture for adult health conditions have rated only a minority of conclusions as high- or moderate-certainty evidence, and most of these were about comparisons with sham treatment or had conclusions of no benefit of acupuncture. Conclusions with moderate or high-certainty evidence that acupuncture is superior to other active therapies were rare.

These findings are sobering for those who had hoped that acupuncture might be effective for a range of conditions. Despite the fact that, during recent years, there have been numerous systematic reviews, the evidence remains negative or flimsy. As 34 reviews originate from China, and as we know about the notorious unreliability of Chinese acupuncture research, this overall result is probably even more negative than the authors make it out to be.

Considering such findings, some people (including the authors of this analysis) feel that we now need more and better acupuncture trials. Yet I wonder whether this is the right approach. Would it not be better to call it a day, concede that acupuncture generates no or only relatively minor effects, and focus our efforts on more promising subjects?

An international team of researchers described retracted papers originating from paper mills, including their characteristics, visibility, and impact over time, and the journals in which they were published. The term paper mill refers to for-profit organizations that engage in the large-scale production and sale of papers to researchers, academics, and students who wish to, or have to, publish in peer-reviewed journals. Many paper mill papers included fabricated data.

All paper mill papers retracted from 1 January 2004 to 26 June 2022 were included in the study. Papers bearing an expression of concern were excluded. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and analyze the trend of retracted paper mill papers over time, and to analyze their impact and visibility by reference to the number of citations received.

In total, 1182 retracted paper mill papers were identified. The publication of the first paper mill paper was in 2004 and the first retraction was in 2016; by 2021, paper mill retractions accounted for 772 (21.8%) of the 3544 total retractions. Overall, retracted paper mill papers were mostly published in journals of the second highest Journal Citation Reports quartile for impact factor (n=529 (44.8%)) and listed four to six authors (n=602 (50.9%)). Of the 1182 papers, almost all listed authors of 1143 (96.8%) paper mill retractions came from Chinese institutions, and 909 (76.9%) listed a hospital as a primary affiliation. 15 journals accounted for 812 (68.7%) of 1182 paper mill retractions, with one journal accounting for 166 (14.0%). Nearly all (n=1083, 93.8%) paper mill retractions had received at least one citation since publication, with a median of 11 (interquartile range 5-22) citations received.

The authors concluded that papers retracted originating from paper mills are increasing in frequency, posing a problem for the research community. Retracted paper mill papers most commonly originated from China and were published in a small number of journals. Nevertheless, detected paper mill papers might be substantially different from those that are not detected. New mechanisms are needed to identify and avoid this relatively new type of misconduct.

China encourages its researchers to publish papers in return for money and career promotions. Furthermore, medical students at Chinese universities are required to produce a scientific paper in order to graduate. Paper mills openly advertise their services on the Internet and maintain a presence on university campuses. The authors of this analysis reference another recent article (authored by two Chinese researchers) that throws more light on the problem:

This study used data from the Retraction Watch website and from published reports on retractions and paper mills to summarize key features of research misconduct in China. Compared with publicized cases of falsified or fabricated data by authors from other countries of the world, the number of Chinese academics exposed for research misconduct has increased dramatically in recent years. Chinese authors do not have to generate fake data or fake peer reviews for themselves because paper mills in China will do the work for them for a price. Major retractions of articles by authors from China were all announced by international publishers. In contrast, there are few reports of retractions announced by China’s domestic publishers. China’s publication requirements for physicians seeking promotions and its leniency toward research misconduct are two major factors promoting the boom of paper mills in China.

As the authors of the new analysis point out: “Fraudulent papers have negative consequences for the scientific community and the general public, engendering distrust in science, false claims of drug or device efficacy, and unjustified academic promotion, among other problems.” On this blog, I have often warned of research originating from China (some might even think that this is becoming an obsession of mine but I do truly think that this is very important). While such fraudulent papers may have a relatively small impact in many areas of healthcare, their influence in the realm of TCM (where the majority of research comes from China) is considerable. In other words, TCM research is infested by fraud to a degree that prevents drawing meaningful conclusions about the value of TCM treatments.

I feel strongly that it is high time for us to do something about this precarious situation. Otherwise, I fear that in the near future no respectable scientist will take TCM seriously.

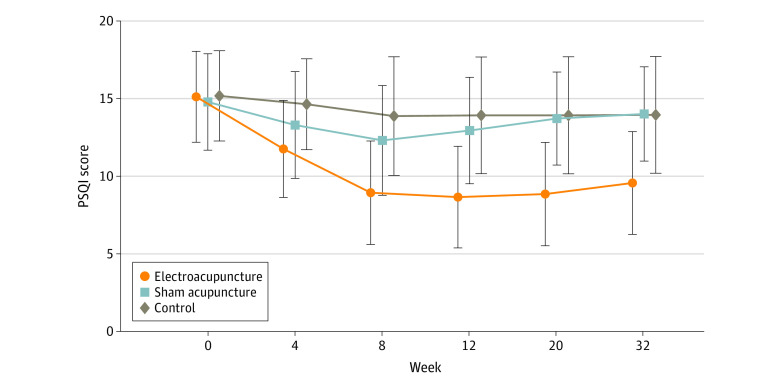

Electroacupuncture (EA) is often advocated for depression and sleep disorders but its efficacy remains uncertain. The aim of this study was, therefore, to “assess the efficacy and safety of EA as an alternative therapy in improving sleep quality and mental state for patients with insomnia and depression.”

A 32-week patient- and assessor-blinded, randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial (8-week intervention plus 24-week follow-up) was conducted from September 1, 2016, to July 30, 2019, at 3 tertiary hospitals in Shanghai, China. Patients were randomized to receive

- EA treatment and standard care,

- sham acupuncture (SA) treatment and standard care,

- standard care only as control.

Patients in the EA or SA groups received a 30-minute treatment 3 times per week (usually every other day except Sunday) for 8 consecutive weeks. All treatments were performed by licensed acupuncturists with at least 5 years of clinical experience. A total of 6 acupuncturists (2 at each center; including X.Y. and S.Z.) performed EA and SA, and they received standardized training on the intervention method before the trial. The regular acupuncture method was applied at the Baihui (GV20), Shenting (GV24), Yintang (GV29), Anmian (EX-HN22), Shenmen (HT7), Neiguan (PC6), and SanYinjiao (SP6) acupuncture points, with 0.25 × 25-mm and 0.30 × 40-mm real needles (Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd), or 0.30 × 30-mm sham needles (Streitberger sham device [Asia-med GmbH]).

For patients in the EA group, rotating or lifting-thrusting manipulation was applied for deqi sensation after needle insertion. The 2 electrodes of the electrostimulator (CMNS6-1 [Wuxi Jiajian Medical Device Co, Ltd]) were connected to the needles at GV20 and GV29, delivering a continuous wave based on the patient’s tolerance. Patients in the SA group felt a pricking sensation when the blunt needle tip touched the skin, but without needle insertion. All indicators of the nearby electrostimulator were set to 0, with the light switched on. Standard care (also known as treatment as usual or routine care) was used in the control group. Patients receiving standard care were recommended by the researchers to get regular exercise, eat a healthy diet, and manage their stress level during the trial. They were asked to keep the regular administration of antidepressants, sedatives, or hypnotics as well. Psychiatrists in the Shanghai Mental Health Center (including X.L.) guided all patients’ standard care treatment and provided professional advice when a patient’s condition changed.

The primary outcome was change in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) from baseline to week 8. Secondary outcomes included PSQI at 12, 20, and 32 weeks of follow-up; sleep parameters recorded in actigraphy; Insomnia Severity Index; 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score; and Self-rating Anxiety Scale score.

Among the 270 patients (194 women [71.9%] and 76 men [28.1%]; mean [SD] age, 50.3 [14.2] years) included in the intention-to-treat analysis, 247 (91.5%) completed all outcome measurements at week 32, and 23 (8.5%) dropped out of the trial. The mean difference in PSQI from baseline to week 8 within the EA group was -6.2 (95% CI, -6.9 to -5.6). At week 8, the difference in PSQI score was -3.6 (95% CI, -4.4 to -2.8; P < .001) between the EA and SA groups and -5.1 (95% CI, -6.0 to -4.2; P < .001) between the EA and control groups. The efficacy of EA in treating insomnia was sustained during the 24-week postintervention follow-up. Significant improvement in the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (-10.7 [95% CI, -11.8 to -9.7]), Insomnia Severity Index (-7.6 [95% CI, -8.5 to -6.7]), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (-2.9 [95% CI, -4.1 to -1.7]) scores and the total sleep time recorded in the actigraphy (29.1 [95% CI, 21.5-36.7] minutes) was observed in the EA group during the 8-week intervention period (P < .001 for all). No between-group differences were found in the frequency of sleep awakenings. No serious adverse events were reported.

The result of the blinding assessment showed that 56 patients (62.2%) in the SA group guessed wrongly about their group assignment (Bang blinding index, −0.4 [95% CI, −0.6 to −0.3]), whereas 15 (16.7%) in the EA group also guessed wrongly (Bang blinding index, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.4-0.7]). This indicated a relatively higher degree of blinding in the SA group.

The authors concluded that, in this randomized clinical trial of EA treatment for insomnia in patients with depression, quality of sleep improved significantly in the EA group compared with the SA or control group at week 8 and was sustained at week 32.

This trial seems rigorous, it has a sizable sample size, uses a credible placebo procedure, and is reported in sufficient detail. Why then am I skeptical?

- Perhaps because we have often discussed how untrustworthy acupuncture studies from China are?

- Perhaps because I fail to see a plausible mechanism of action?

- Perhaps because the acupuncturists could not be blinded and thus might have influenced the outcome?

- Perhaps because the effects of sham acupuncture seem unreasonably small?

- Perhaps because I cannot be sure whether the acupuncture or the electrical current is supposed to have caused the effects?

- Perhaps because the authors of the study are from institutions such as the Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Huadong Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai,

- Perhaps because the results seem too good to be true?

If you have other and better reasons, I’d be most interested to hear them.

Even though most people do not think about it in this way, tea is a herbal remedy. We know that it is pleasant, but is it also effective?

This study explored the associations between tea drinking and the incident risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus(T2 DM). A dynamic prospective cohort study among a total of 27 841 diabetes-free permanent adult residents randomly selected from 2, 6, and 7 rural communities between 2006-2008, 2011-2012, and 2013-2014, respectively. Questionnaire survey, physical examination, and laboratory test were carried out among the participants. In 2018, the researchers conducted a follow-up through the electronic health records of residents. Cox regression models were applied to explore the association between tea drinking and the incident risk of T2 DM and estimate the hazard ratio(HR), and its 95%CI.

Among the 27 841 rural community residents in Deqing County, 10 726(39%) were tea drinkers, 8215 (77%) of which were green tea drinkers. A total of 883 new T2 DM incidents were identified until December 31, 2018, and the incidence density was 4.43 per 1000 person-years (PYs). The incidence density was 4.07/1000 PYs in those with tea drinking habits and 4.71/1000 PYs in those without tea drinking habits. The incidence density was 3.79/1000 PYs in those with green tea drinking habits. After controlling for sex, age, education, farming, smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary preference, body mass index, hypertension, impaired fasting glucose, and family history of diabetes, the risk of T2 DM among rural residents with tea drinking habits was 0.79 times higher than that among residents without tea drinking habits(HR=0.79, 95%CI 0.65-0.96), and the risk of T2 DM among residents with green tea drinking habits was 0.72 times higher than that among residents without tea drinking habits(HR=0.72, 95%CI 0.58-0.89). No significant associations were found between other kinds of tea and the risk of T2 DM, nor the amount of green tea-drinking.

The authors concluded that drinking green tea may reduce the risk of T2 DM among adult population in rural China.

Epidemiological studies of this nature resemble big fishing expeditions that can bring up all sorts of rubbish and – if lucky – also some fish. The question thus is whether this study identified an interesting association or just some odd rubbish.

A quick look into Medline seems to suggest great caution. Here are the conclusions from a few further case-control studies:

- In Chinese adults, daily green tea consumption was associated with a lower risk of incident T2D and a lower risk of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes, but the associations for other types of tea were less clear. In addition, daily tea consumption was associated with a lower risk of diabetic microvascular complications, but not macrovascular complications.

- Green tea drinking was associated with an increased risk of T2D in Chinese adults. The mechanisms underlying the association need to be elucidated.

- Tea consumers had reduced risks of all-cause mortality and partial cause-specific mortality, but not for the risk of death from cancer. On the contrary, daily tea drinkers with smoking habits and excessive alcohol drinking had an increased risk of death from cancer.

Thus the question of whether tea drinking might prevent diabetes remains open, in my view.

Yet, the paper might teach us two important lessons:

- Case-control studies must be taken with a pinch of salt.

- Correlation is not the same as causation.

Earlier this year, I started the ‘WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION’. As a competition without a prize is no fun, I am offering the winner (that is the lead author of the winning paper) one of my books that best fits his/her subject. I am sure this will overjoy him or her.

And how do we identify the winner? I will continue blogging about nominated papers (I hope to identify about 10 in total), and towards the end of the year, I let my readers decide democratically.

In this spirit of democratic voting, let me suggest to you ENTRY No 8 (it is so impressive that I must show you the unadulterated abstract):

Introduction

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) seriously affects the quality of life of women. However, most women do not have access to effective treatment.

Aim

This study aimed to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of the use of acupuncture in FSD treatment based on existing clear acupuncture protocol and experience-supported face-to-face therapy.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on 24 patients with FSD who received acupuncture from October 2018 to February 2022. The Chinese version of the female sexual function index , subjective sensation, sexual desire, sexual arousal, vaginal lubrication, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, and dyspareunia scores were compared before and after the treatment in all 24 patients.

Main Outcome Measure

A specific female sexual function index questionnaire was used to assess changes in female sexual function before and after the acupuncture treatment.

Results

In this study, the overall treatment improvement rate of FSD was 100%. The Chinese version of the female sexual function index total score, sexual desire score, sexual arousal score, vaginal lubrication score, orgasm score, sexual satisfaction score, and dyspareunia score during intercourse were significantly different before and after the treatment (P < .05). Consequently, participants reported high levels of satisfaction with acupuncture. This study indicates that acupuncture could be a new and effective technique for treating FSD. The main advantages of this study are its design and efficacy in treating FSD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of FSD using the female sexual function index scale from 6 dimensions. The second advantage is that the method used (ie, the nonpharmacological method) is simple, readily available, highly safe with few side effects, and relatively inexpensive with high patient satisfaction. However, limitations include small sample size and lack of further detailed grouping, pre and post control study of patients, blank control group, and pre and post control study of sex hormones.

Conclusion

Acupuncture can effectively treat FSD from all dimensions with high safety, good satisfaction, and definite curative effect, and thus, it is worthy of promotion and application.

My conclusion is very different: acupuncture can effectively kill any ability for critical thinking.

I hardly need to list the flaws of this paper – they are all too obvious, e.g.:

- there is no control group; the results might therefore be due to a host of factors that are unrelated to acupuncture,

- the trial was too small to allow far-reaching conclusions,

- the study does not tell us anything about the safety of acupuncture.

The authors call their investigation a ‘pilot study’. Does that excuse the flimsiness of their effort? No! A pilot study cannot draw conclusions such as the above.

What’s the harm? you might ask; nobody will ever read such rubbish and nobody will have the bizarre idea to use acupuncture for treating FSD. I’m afraid you would be wrong to argue in this way. The paper already got picked up by THE DAILY MAIL in an article entitled “Flailing libido? Acupuncture could help boost sex drive, scientists say” which was as devoid of critical thinking as the original study. Thus we can expect that hundreds of desperate women are already getting needled and ripped off as we speak. And in any case, offensively poor science is always harmful; it undermines public trust in research (and it renders acupuncture research the laughing stock of serious scientists).

Should Acupuncture-Related Therapies be Considered in Prediabetes Control?

No!

If you are pre-diabetic, consult a doctor and follow his/her advice. Do NOT do what acupuncturists or other self-appointed experts tell you. Do NOT become a victim of quackery.

But the authors of a new paper disagree with my view.

So, let’s have a look at the evidence.

Their systematic review was aimed at evaluating the effects and safety of acupuncture-related therapy (AT) interventions on glycemic control for prediabetes. The Chinese researchers searched 14 databases and 5 clinical registry platforms from inception to December 2020. Randomized controlled trials involving AT interventions for managing prediabetes were included.

Of the 855 identified trials, 34 articles were included for qualitative synthesis, 31 of which were included in the final meta-analysis. Compared with usual care, sham intervention, or conventional medicine, AT treatments yielded greater reductions in the primary outcomes, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (standard mean difference [SMD] = -0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.06, -0.61; P < .00001), 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) (SMD = -0.88; 95% CI, -1.20, -0.57; P < .00001), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (SMD = -0.91; 95% CI, -1.31, -0.51; P < .00001), as well as a greater decline in the secondary outcome, which is the incidence of prediabetes (RR = 1.43; 95% CI, 1.26, 1.63; P < .00001).

The authors concluded that AT is a potential strategy that can contribute to better glycemic control in the management of prediabetes. Because of the substantial clinical heterogeneity, the effect estimates should be interpreted with caution. More research is required for different ethnic groups and long-term effectiveness.

But this is clearly a positive result!

Why do I not believe it?

There are several reasons:

- There is no conceivable mechanism by which AT prevents diabetes.

- The findings heavily rely on Chinese RCTs which are known to be of poor quality and often even fabricated. To trust such research would be a dangerous mistake.

- Many of the primary studies were designed such that they failed to control for non-specific effects of AT. This means that a causal link between AT and the outcome is doubtful.

- The review was published in a 3rd class journal of no impact. Its peer-review system evidently failed.

So, let’s just forget about this rubbish paper?

If only it were so easy!

Journalists always have a keen interest in exotic treatments that contradict established wisdom. Predictably, they have been reporting about the new review thus confusing or misleading the public. One journalist, for instance, stated:

Acupuncture has been used for thousands of years to treat a variety of illnesses — and now it could also help fight one of the 21st century’s biggest health challenges.

New research from Edith Cowan University has found acupuncture therapy may be a useful tool in avoiding type 2 diabetes.

The team of scientists investigated dozens of studies covering the effects of acupuncture on more than 3600 people with prediabetes. This is a condition marked by higher-than-normal blood glucose levels without being high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes.

According to the findings, acupuncture therapy significantly improved key markers, such as fasting plasma glucose, two-hour plasma glucose, and glycated hemoglobin. Additionally, acupuncture therapy resulted in a greater decline in the incidence of prediabetes.

The review can thus serve as a prime example for demonstrating how irresponsible research has the power to mislead millions. This is why I have often said that poor research is a danger to public health.

And what can be done about this more and more prevalent problem?

The answer is easy: people need to behave more responsibly; this includes:

- trialists,

- review authors,

- editors,

- peer-reviewers,

- journalists.

Yes, the answer is easy in theory – but the practice is far from it!

The US Food and Drug Administration created the Tainted Dietary Supplement Database in 2007 to identify dietary supplements adulterated with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). This article compared API adulterations in dietary supplements from the 10-year time period of 2007 through 2016 to the most recent 5-year period of 2017 through 2021. Its findings are alarming:

- From 2007 through 2021, 1068 unique products were found to be adulterated with APIs.

- Sexual enhancement and weight-loss dietary supplements are the most common products adulterated with APIs.

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are commonly included in sexual enhancement dietary supplements.

- A single product can include up to 5 APIs.

- Sibutramine, a drug removed from the market due to cardiovascular adverse events, is the most included adulterant API in weight loss products.

- Sibutramine analogues, phenolphthalein (which was removed from the US market because of cancer risk), and fluoxetine were also included.

- Muscle-building dietary supplements were commonly adulterated before 2016, but since 2017 no additional adulterated products have been identified.

The authors concluded that the lack of disclosure of APIs in dietary supplements, circumventing the normal procedure with clinician oversight of prescription drug use, and the use of APIs that are banned by the Food and Drug Administration or used in combinations that were never studied are important health risks for consumers.

The problem of adulterated supplements is by no means new. A similar review published 4 years ago already warned that “active pharmaceuticals continue to be identified in dietary supplements, especially those marketed for sexual enhancement or weight loss, even after FDA warnings. The drug ingredients in these dietary supplements have the potential to cause serious adverse health effects owing to accidental misuse, overuse, or interaction with other medications, underlying health conditions, or other pharmaceuticals within the supplement.”

These papers relate to the US where supplement use is highly prevalent. The harm done by adulterated products is thus huge. If we focus on Chinese or Ayurvedic supplements, the problem might even be more serious. In 2002, my own review concluded that adulteration of Chinese herbal medicines with synthetic drugs is a potentially serious problem which needs to be addressed by adequate regulatory measures. Twenty years later, we seem to be still waiting for effective regulations that protect the consumer.

Progress in medicine, they say, is made funeral by funeral!

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) related to cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality and an important issue of public health worldwide. The cost of long-term healthcare for IHD patients may result in a huge financial burden. This study analyzed the medical expenditure incurred for and survival of IHD patients treated with Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) and Western medicine.

Subjects were randomly selected from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. The Cox proportional hazards regression model, Kaplan–Meier estimator, logrank test, chi-square test, and analysis of variance were applied. Landmark analysis was used to assess the cumulative incidence of death in IHD patients.

A total of 11,527 users were identified as CHM combined with Western medicine and 11,527 non-CHM users. CHM users incurred a higher medical expenditure for outpatient care within 1 (24,529 NTD versus 18,464 NTD, value <0.0001) and 5 years (95,345 NTD versus 60,367 NTD, value <0.0001). However, CHM users had shorter hospitalizations and lower inpatient medical expenditure (7 days/43,394 NTD in 1 year; 11 days/83,141 NTD in 5 years) than non-CHM users (11 days/72,939 NTD in 1 year; 14 days/107,436 NTD in 5 years).

The CHM group’s adjusted hazard ratio for mortality was 0.41 lower than that of the non-CHM group by Cox proportional hazard models with time-dependent exposure covariates. Danshen, Huang qi, Niu xi, Da huang, and Fu zi were the most commonly prescribed Chinese single herbs; Zhi-Gan-Cao-Tang, Xue-Fu-Zhu-Yu-Tang, Tian-Wang-Bu-Xin-Dan, Sheng-Mai-San, and Yang-Xin-Tang were the five most frequently prescribed herbal formulas in Taiwan.

The authors concluded that combining Chinese and Western medicine can reduce hospital expenditure and improve survival for IHD patients.

Why, you will ask, do I think that this study deserves to be in the ‘worst paper cometition’?

It is not so bad!

It is an epidemiological case-control study with a large sample size that generates interesting findings.

Agreed!

But, as a case-control study, it cannot establish a causal link between CHM and the outcomes. You might argue that the conclusions avoid doing this – “can … improve survival” is not the same as “does improve survival”. This may be true, yet the title of the article leaves little doubt about the interpretation of the authors:

Chinese Herbal Medicine as an Adjunctive Therapy Improves the Survival Rate of Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study

I find it difficult not to view this as a deliberate attempt of the authors, editors, and reviewers to mislead the public.

Looking at the details of the study, it is easy to see that the two groups were different in a whole range of parameters that were measured. More importantly, they most likely differ in a range of variables that were not measured and had significant influence on IHD survival. It stands to reason, for instance, that patients who elected to use CHM in addition to their standard care were more health conscious. They would thus have followed a healthier diet and lifestyle. It would be foolish to claim that such factors do not influence IHD survival.

The fact that the authors fail even to mention this possibility, interpret an association as a causal link, and thus try to mislead us all makes this paper, in my view, a strong contender for my

WORST PAPER OF 2022 COMPETITION