bogus claims

So sorry, I have been neglecting THE ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME of late. I was reminded of its existence when writing my post about Adrian White the other day. Reading the kind comments I received on it, I not only decided to make Adrian an honorary member (for his latter part of his career as an acupuncture researcher, but also to reactivate the idea of the HALL OF FAME in more general terms. And in the course of doing just this, I noticed that I somehow forgot to admit Prof Michael Frass, an omission which I regret and herewith rectify. A warm welcome to both!

In case you are unaware what THE ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME is, let me explain: it is a group of researchers who manage to go through (part of) their professional life researching their particular SCAM without ever publishing a negative conclusion about it, or who have other outstanding merits in misleading the public about so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). As of today, we thus have the following experts in the HALL:

Adrian White (acupuncturist, UK)

Michael Frass (homeopath, Austria)

Jens Behnke (research officer, Germany)

John Weeks (editor of JCAM, US)

Deepak Chopra (entrepreneur, Us)

Cheryl Hawk (US chiropractor)

David Peters (osteopathy, homeopathy, UK)

Nicola Robinson (TCM, UK)

Peter Fisher (homeopathy, UK)

Simon Mills (herbal medicine, UK)

Gustav Dobos (various, Germany)

Claudia Witt (homeopathy, Germany and Switzerland)

George Lewith (acupuncture, UK)

John Licciardone (osteopathy, US)

I must say, this is an assembly of international SCAM experts to be proud of – even if I say so myself!

The new member I am proposing to admit today is Dr Jenice Pellow. She is a lecturer in the Department of Complementary Medicine at the University of Johannisburg and already once featured on this blog. But now it seems time to admit this relatively little-known researcher into my HALL OF FAME. Dr Pellow has 11 Medline-listed papers on so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Allow me to show you some key findings from their abstracts:

- Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) offers parents various treatment options for this condition [ADHD], including dietary modifications, nutritional supplementation, herbal medicine, and homeopathy. CAM appears to be most effective when prescribed holistically and according to each individual’s characteristic symptoms.

- The homeopathic medicine reduced the sensitivity reaction of cat allergic adults to cat allergen, according to the SPT. Future studies are warranted to further investigate the effect of Cat saliva and Histaminum and their role as a potential therapeutic option for this condition.

- Findings suggest that daily use of the homeopathic complex does have an effect over a 4-wk period on physiological and cognitive arousal at bedtime as well as on sleep onset latency in PI sufferers. Further research on the use of this complex for PI is warranted before any definitive conclusions can be drawn.

- The homeopathic complex used in this study exhibited significant anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving qualities in children with acute viral tonsillitis. No patients reported any adverse effects. These preliminary findings are promising; however, the sample size was small and therefore a definitive conclusion cannot be reached. A larger, more inclusive research study should be undertaken to verify the findings of this study.

- …results suggest the homeopathic complex, together with physiotherapy, can significantly improve symptoms associated with CLBP due to OA.

- This small study showed the potential benefits of individualized homeopathic treatment of binge eating in males, decreasing both the frequency and severity of binging episodes.

- There have been numerous trials and pharmacological studies of specific herbal preparations related to the treatment of low sexual desire.

- Most of the evaluated medicinal plants showed evidence of efficacy in relieving menstrual pain in at least one RCT.

- Results indicated that most participants made use of both complementary and conventional medicines for their infant’s colic; the most commonly used complementary medicine products were homeopathic remedies, probiotics and herbal medicines.

- Promising evidence for the following single supplements were found [for allergic rhinitis]: apple polyphenols, tomato extract, spirulina, chlorophyll c2, honey, conjugated linoleic acid, MSM, isoquercitrin, vitamins C, D and E, as well as probiotics. Combination formulas may also be beneficial, particularly specific probiotic complexes, a mixture of vitamin D3, quercetin and Perilla frutescens, as well as the combination of vitamin D3 and L. reuteri.

- Despite a reported lack of knowledge regarding complementary medicine and limited personal use, participants had an overall positive attitude towards complementary medicine.

I admit that 11 papers in 7 years is not an overwhelming output for a University lecturer. However, please do consider the fact that all of them – particularly the ones on homeopathy which is be the particular focus of Jenice (after all, she is a homeopath) – chime a happy tune for SCAM. I therefore think that Jenice should be admitted to THE ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME and hope you agree.

Welcome to ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME, Jenice!

As though the UK does not have plenty of organisations promoting so-called alternative medicine (SCAM)! Obviously not – because a new one is about to emerge.

In mid-January, THE COLLEGE OF MEDICINE AND INTEGRATED HEALTH (COMIH) will launch the Integrated Medicine Alliance bringing together the leaders of many complementary health organisations to provide patients, clinicians and policy makers with information on the various complementary modalities, which will be needed in a post COVID-19 world, where:

- patient choice is better respected,

- requirements for evidence of efficacy are more proportionate to the seriousness of the disease and the safety of the intervention,

- and where benefit versus risk are better balanced.

We already saw this in 2020 with the College advocating from the very beginning of the year that people should think about taking Vitamin D, while the National Institute for Clinical Excellence continued to say the evidence was insufficient, but the Secretary of State has now supported it being given to the vulnerable on the basis of the balance between cost, benefit and safety.

Elsewhere we learn more about the Integrated Medicine Alliance (IMA):

The IMA is a group of organisations and individuals that have been brought together for the purpose of encouraging and optimising the best use of complementary therapies alongside conventional healthcare for the benefit of all.

The idea for this group was conceived by Dr Michael Dixon in discussion with colleagues associated with the College of Medicine, and the initial meeting to convene the group was held in February 2019.

The group transitioned through a number of titles before settling on the ‘Integrated Medicine Alliance’ and began work on developing a patient leaflet and a series of information sheets on the key complementary therapies.

It was agreed that in the first instance the IMA should exist under the wing of the College of Medicine, but that in the future it may develop into a formal organisation in its own right, but inevitably maintaining a close relationship with the College of Medicine.

The IMA also offers ‘INFORMATION SHEETS’ on the following modalities:

- Acupuncture

- Alexander Technique

- Aromatherapy

- Herbal Medicine

- Homeopathy

- Hypnotherapy

- Massage

- Naturopathy

- Reflexology

- Reiki

- Tai Chi

- Yoga Therapy

I find those leaflets revealing. They tell us, for example that the Reiki practitioner channels universal energy through their hands to help rebalance each of the body’s energy centres, known as chakras. About homeopathy, we learn that a large corpus of evidence has accumulated which stands the most robust tests of modern science. And about naturopathy, we learn that it includes ozone therapy but is perfectly safe.

Just for the fun of it – and free of charge – let me try to place a few corrections here:

- Reiki healers use their hands to perform what is little more than a party trick.

- The universal energy they claim to direct does not exist.

- The body does not have energy centres.

- Chakras are a figment of imagination.

- The corpus of evidence on homeopathy is by no means large.

- The evidence is flimsy.

- The most robust tests of modern science fail to show that homeopathy is effective beyond placebo.

- Naturopathy is a hotchpotch of treatments most of which are neither natural nor perfectly safe.

One does wonder who writes such drivel for the COMIH, and one shudders to think what else the IMA might be up to.

I was criticised for not referencing this article in a recent post on adverse effects of spinal manipulation. In fact the commentator wrote: Shame on you Prof. Ernst. You get an “E” for effort and I hope you can do better next time. The paper was published in a third-class journal, but I will nevertheless quote the ‘key messages’ from this paper, because they are in many ways remarkable.

- Adverse events from manual therapy are few, mild, and transient. Common AEs include local tenderness, tiredness, and headache. Other moderate and severe adverse events (AEs) are rare, while serious AEs are very rare.

- Serious AEs can include spinal cord injuries with severe neurological consequences and cervical artery dissection (CAD), but the rarity of such events makes the provision of epidemiological evidence challenging.

- Sports-related practice is often time sensitive; thus, the manual therapist needs to be aware of common and rare AEs specifically associated with spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) to fully evaluate the risk-benefit ratio.

The author of this paper is Aleksander Chaibi, PT, DC, PhD who holds several positions in the Norwegian Chiropractors’ Association, and currently holds a position as an expert advisor in the field of biomedical brain research for the Brain Foundation of the Netherlands. I feel that he might benefit from reading some more critical texts on the subject. In fact, I recommend my own 2020 book. Here are a few passages dealing with the safety of SMT:

Relatively minor AEs after SMT are extremely common. Our own systematic review of 2002 found that they occur in approximately half of all patients receiving SMT. A more recent study of 771 Finish patients having chiropractic SMT showed an even higher rate; AEs were reported in 81% of women and 66% of men, and a total of 178 AEs were rated as moderate to severe. Two further studies reported that such AEs occur in 61% and 30% of patients. Local or radiating pain, headache, and tiredness are the most frequent adverse effects…

A 2017 systematic review identified the characteristics of AEs occurring after cervical spinal manipulation or cervical mobilization. A total of 227 cases were found; 66% of them had been treated by chiropractors. Manipulation was reported in 95% of the cases, and neck pain was the most frequent indication for the treatment. Cervical arterial dissection (CAD) was reported in 57%, and 46% had immediate onset symptoms. The authors of this review concluded that there seems to be under-reporting of cases. Further research should focus on a more uniform and complete registration of AEs using standardized terminology…

In 2005, I published a systematic review of ophthalmic AEs after SMT. At the time, there were 14 published case reports. Clinical symptoms and signs included:

- central retinal artery occlusion,

- nystagmus,

- Wallenberg syndrome,

- ptosis,

- loss of vision,

- ophthalmoplegia,

- diplopia,

- Horner’s syndrome…

Vascular accidents are the most frequent serious AEs after chiropractic SMT, but they are certainly not the only complications that have been reported. Other AEs include:

- atlantoaxial dislocation,

- cauda equina syndrome,

- cervical radiculopathy,

- diaphragmatic paralysis,

- disrupted fracture healing,

- dural sleeve injury,

- haematoma,

- haematothorax,

- haemorrhagic cysts,

- muscle abscess,

- muscle abscess,

- myelopathy,

- neurologic compromise,

- oesophageal rupture

- pneumothorax,

- pseudoaneurysm,

- soft tissue trauma,

- spinal cord injury,

- vertebral disc herniation,

- vertebral fracture…

In 2010, I reviewed all the reports of deaths after chiropractic treatments published in the medical literature. My article covered 26 fatalities but it is important to stress that many more might have remained unpublished. The cause usually was a vascular accident involving the dissection of a vertebral artery (see above). The review also makes the following important points:

- … numerous deaths have been associated with chiropractic. Usually high-velocity, short-lever thrusts of the upper spine with rotation are implicated. They are believed to cause vertebral arterial dissection in predisposed individuals which, in turn, can lead to a chain of events including stroke and death. Many chiropractors claim that, because arterial dissection can also occur spontaneously, causality between the chiropractic intervention and arterial dissection is not proven. However, when carefully evaluating the known facts, one does arrive at the conclusion that causality is at least likely. Even if it were merely a remote possibility, the precautionary principle in healthcare would mean that neck manipulations should be considered unsafe until proven otherwise. Moreover, there is no good evidence for assuming that neck manipulation is an effective therapy for any medical condition. Thus, the risk-benefit balance for chiropractic neck manipulation fails to be positive.

- Reliable estimates of the frequency of vascular accidents are prevented by the fact that underreporting is known to be substantial. In a survey of UK neurologists, for instance, under-reporting of serious complications was 100%. Those cases which are published often turn out to be incomplete. Of 40 case reports of serious adverse effects associated with spinal manipulation, nine failed to provide any information about the clinical outcome. Incomplete reporting of outcomes might therefore further increase the true number of fatalities.

- This review is focussed on deaths after chiropractic, yet neck manipulations are, of course, used by other healthcare professionals as well. The reason for this focus is simple: chiropractors are more frequently associated with serious manipulation-related adverse effects than osteopaths, physiotherapists, doctors or other professionals. Of the 40 cases of serious adverse effects mentioned above, 28 can be traced back to a chiropractor and none to a osteopath. A review of complications after spinal manipulations by any type of healthcare professional included three deaths related to osteopaths, nine to medical practitioners, none to a physiotherapist, one to a naturopath and 17 to chiropractors. This article also summarised a total of 265 vascular accidents of which 142 were linked to chiropractors. Another review of complications after neck manipulations published by 1997 included 177 vascular accidents, 32 of which were fatal. The vast majority of these cases were associated with chiropractic and none with physiotherapy. The most obvious explanation for the dominance of chiropractic is that chiropractors routinely employ high-velocity, short-lever thrusts on the upper spine with a rotational element, while the other healthcare professionals use them much more sparingly.

Another review summarised published cases of injuries associated with cervical manipulation in China. A total of 156 cases were found. They included the following problems:

- syncope (45 cases),

- mild spinal cord injury or compression (34 cases),

- nerve root injury (24 cases),

- ineffective treatment/symptom increased (11 cases),

- cervical spine fracture (11 cases),

- dislocation or semi-luxation (6 cases),

- soft tissue injury (3 cases),

- serious accident (22 cases) including paralysis, deaths and cerebrovascular accidents.

Manipulation including rotation was involved in 42% of all cases. In total, 5 patients died…

To sum up … chiropractic SMT can cause a wide range of very serious complications which occasionally can even be fatal. As there is no AE reporting system of such events, we nobody can be sure how frequently they occur.

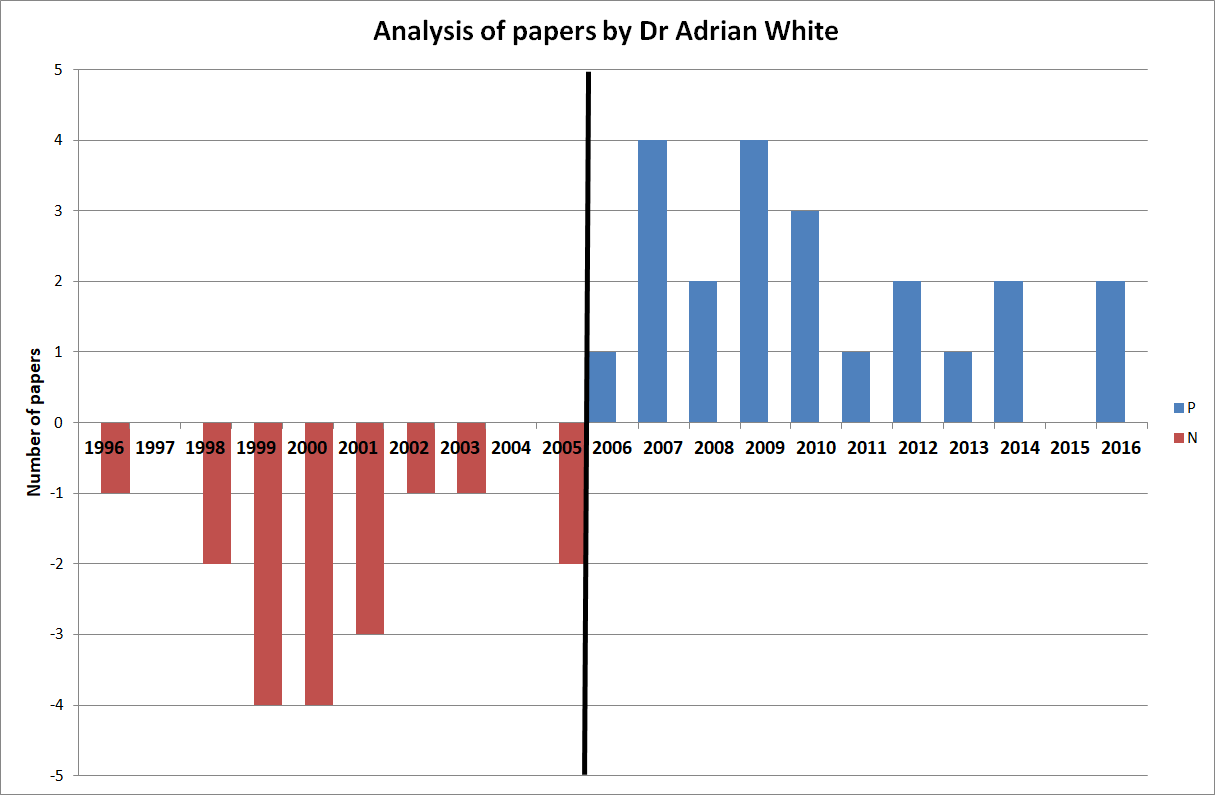

[references from my text can be found in the book]This is an analysis that I have long hesitated to conduct. The reason for my hesitation is simple: some people might think it is vindictive, revengeful or ad hominem. After reflecting about it for years, I have now decided to go ahead with it (sorry, it’s a bit lengthy). This case study is not meant to be vindictive, but offers an important insight into the power of conflicts of interest in SCAM that are not financial but ideological. I think it is crucial that people are aware of and consider such conflicts carefully, and I can’t see how else I might demonstrate my point so plainly.

Dr Adrian White was a co-worker of mine for about 10 years. He became a trusted colleague, my ‘right hand’ man and even my deputy at my Exeter department. When I discovered that my trust had been misplaced, I did not prolong his contract (I will not dwell on this episode, those who are interested find it in my memoir). Adrian then got a senior research fellowship with Prof John Campbell (not my favourite colleague at Exeter) at the department of general practice where he continued his research on acupuncture for about 10 more years largely unsupervised.

Adrian had been an acupuncturist body and soul (in fact, I had never before met anyone so utterly convinced of the value of this therapy). When he joined my team, he was scientifically naive, and we spent many month trying to teach him how to think like a scientist. Initially, he found it very difficult to think critically about acupuncture. Later, I thought the problem was under control. Yet, most of his research in my department was guided by me and tightly supervised (i.e. I made sure that out studies were testing rather than promoting SCAM, and that our reviews were critical assessments of the existing evidence).

Thus there exist two separate and well-documented periods of a pro-acupuncture researcher:

- 10 years guided by me and members of my team;

- 10 years largely unsupervised.

What could be more tempting than to compare Adrian’s output during these two periods?

To do this, I looked up all of Adrian’s 120 publications on acupuncture and selected those 52 articles that generated factual new data (mostly clinical trials or systematic reviews). As it happens, they are numerically distributed almost equally within the two periods. The endpoints for my analysis were the directions of the conclusions of his papers. I therefore extracted, dated, and rated the 52 articles as follows:

- P = positive from the point of view of an acupuncture advocate,

- N = negative from the point of view of an acupuncture advocate.

- P/N = not clearly pointing in either direction.

To render this exercise transparent (occasionally, I was not entirely sure about my ratings), I copied all the 52 conclusions and provided links to the original papers so that anyone inferested is able to check easily.

Here are my findings. Articles 1 – 27 were published AFTER Adrian had left my department; articles 28 – 52 are his papers from the time while he worked with me.

- A definitive three-arm trial is feasible. Further follow-up reminders, minimum data collection and incentives should be considered to improve participant retention in the follow-up processes in the standardised advice and exercise booklet arm. (2016) P/N

- The available evidence suggests that adding acupuncture to symptomatic treatment of attacks reduces the frequency of headaches. Contrary to the previous findings, the updated evidence also suggests that there is an effect over sham, but this effect is small. The available trials also suggest that acupuncture may be at least similarly effective as treatment with prophylactic drugs. Acupuncture can be considered a treatment option for patients willing to undergo this treatment. As for other migraine treatments, long-term studies, more than one year in duration, are lacking. (2016) P

- The available results suggest that acupuncture is effective for treating frequent episodic or chronic tension-type headaches, but further trials – particularly comparing acupuncture with other treatment options – are needed. (2016) P

- Acupuncture during pregnancy appears to be associated with few AEs when correctly applied. (2014) P

- Although pooled estimates suggest possible short-term effects there is no consistent, bias-free evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, or laser therapy have a sustained benefit on smoking cessation for six months or more. However, lack of evidence and methodological problems mean that no firm conclusions can be drawn. Electrostimulation is not effective for smoking cessation. Well-designed research into acupuncture, acupressure and laser stimulation is justified since these are popular interventions and safe when correctly applied, though these interventions alone are likely to be less effective than evidence-based interventions. (2014) P

- The current evidence suggests that acupuncture may have some effects on drug dependence that have been missed because of choice of outcome in many previous studies, and future studies should use outcomes suggested by clinical experience. Body points and electroacupuncture, used in the original clinical observation, justify further research. (2013) P

- Acceptability is very high and may be maximised by taking a number of factors into account: full information should be provided before treatment begins; flexibility should be maintained in the appointment system and different levels of contact between fellow patients should be fostered; sufficient space and staffing should be provided and single-sex groups used wherever possible. (2012) P

- This is the first evaluation of nurse-led group (multibed) acupuncture clinics for patients with knee osteoarthritis to include a 2 year follow-up. It shows the practicability of offering a low-cost acupuncture service as an alternative to knee surgery and the service’s success in providing long-term symptom relief in about a third of patients. Using realistic assumptions, the cost consequences for the local commissioning group are an estimated saving of £100 000 a year. Sensitivity analyses are presented using different assumptions. (2012) P

- There is no consistent, bias-free evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy or electrostimulation are effective for smoking cessation, but lack of evidence and methodological problems mean that no firm conclusions can be drawn. Further, well designed research into acupuncture, acupressure and laser stimulation is justified since these are popular interventions and safe when correctly applied, though these interventions alone are likely to be less effective than evidence-based interventions. (2011) P/N

- Eight (8) of 10 international acupuncture experts were able to reach consensus on the syndromes, symptoms, and treatment of postmenopausal women with hot flashes. The syndromes were similar to those used by practitioners in the ACUFLASH clinical trial, but there were considerable differences between the acupuncture points. This difference is likely to be the result of differences in approach of training schools, and whether it is relevant for clinical outcomes is not well understood. (2011) P

- 70% of those patients eligible to participate volunteered to do so; all participants had clinically identified MTrPs; a 100% completion rate was achieved for recorded self-assessment data; no serious adverse events were reported as a result of either intervention; and the end of treatment attrition rate was 17%. A phase III study is both feasible and clinically relevant. This study is currently being planned. (2010) P

- In conclusion, the results from all studies are in agreement with the hypothesis that acupuncture needling relieves hot flushes. There are few data however supporting the hypothesis that the effect of acupuncture is point specific. Future research should investigate whether there is a biological effect of needling on hot flushes or not, whether tailored treatment is superior to standardised treatment, and ways of delivering treatment that causes least discomfort and least cost. (2010) P

- Acupuncture can contribute to a more rapid reduction in vasomotor symptoms and increase in health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women but probably has no long-term effects. (2010) P

- within the context of this pilot study, the sham acupuncture intervention was found to be a credible control for acupuncture. This supports its use in a planned, definitive, randomised controlled trial on a similar whiplash injured population. (2009) N/P

- factors other than the TCM syndrome diagnoses and the point selection may be of importance regarding the outcome of the treatment. (2009) N/P

- Acupuncture plus self-care can contribute to a clinically relevant reduction in hot flashes and increased health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women. (2009) P

- the authors conclude that acupuncture could be a valuable non-pharmacological tool in patients with frequent episodic or chronic tension-type headaches. (2009) P

- there is consistent evidence that acupuncture provides additional benefit to treatment of acute migraine attacks only or to routine care. There is no evidence for an effect of ‘true’ acupuncture over sham interventions, though this is difficult to interpret, as exact point location could be of limited importance. Available studies suggest that acupuncture is at least as effective as, or possibly more effective than, prophylactic drug treatment, and has fewer adverse effects. Acupuncture should be considered a treatment option for patients willing to undergo this treatment. (2009) P

- We have conducted the first survey of the effects of provision of acupuncture in UK general practice, using data provided by the NHS, and uncovered a wide variation in the availability of the service in different areas. We have been unable to demonstrate any consistent differences in the prescribing or referral rates that could be due to the use of acupuncture in these practices. The wide variation in the data means that if such a trend exists, a very large survey would be needed to identify it. However, we discovered inaccuracies and variations in presentation of data by the PCTs which have made the numerical input, and hence our results, unreliable. Thus the practicalities of access to data and the problems with data accuracy would preclude a nationwide survey. (2008) P

- In conclusion, there is limited evidence deriving from one study that deep needling directly into myofascial trigger points has an overall treatment effect when compared with standardised care. Whilst the result of the meta-analysis of needling compared with placebo controls does not attain statistically significant, the overall direction could be compatible with a treatment effect of dry needling on myofascial trigger point pain. However, the limited sample size and poor quality of these studies highlights and supports the need for large scale, good quality placebo controlled trials in this area. (2009) P

- We conclude that limited evidence supports acupuncture use in treating pregnancy-related pelvic and back pain. Additional high-quality trials are needed to test the existing promising evidence for this relatively safe and popular complementary therapy. (2008) P

- Acupuncture appears to offer symptomatic improvement to some patients with fibromyalgia in a tertiary clinic who have failed to respond to other treatments. In view of its safety, further acupuncture research is justified in this population. (2007) P

- It is speculated that optimal results from acupuncture treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee may involve: climatic factors, particularly high temperature; high expectations of patients; minimum of four needles; electroacupuncture rather than manual acupuncture, and particularly, strong electrical stimulation to needles placed in muscle; and a course of at least 10 treatments. These factors offer some support to criteria for adequate acupuncture used in the recent review. In addition, ethnic and cultural factors may influence patients’ reporting of their symptoms, and different versions of an outcome measure are likely to differ in their sensitivity – both factors which may lead to apparent rather than real differences between studies. The many variables in a study are likely to be more tightly controlled in a single centre study than in multicentre studies. (2007) P

- Any effects of acupressure on smoking withdrawal, as an adjunct to the use of NRT and behavioural intervention, are unlikely to be detectable by the methods used here and further preliminary studies are required before the hypothesis can be tested. (2007) P

- Auricular acupuncture appears to be effective for smoking cessation, but the effect may not depend on point location. This calls into question the somatotopic model underlying auricular acupuncture and suggests a need to re-evaluate sham controlled studies which have used ‘incorrect’ points. Further experiments are necessary to confirm or refute these observational conclusions. (2006) P

- Acupuncture that meets criteria for adequate treatment is significantly superior to sham acupuncture and to no additional intervention in improving pain and function in patients with chronic knee pain. Due to the heterogeneity in the results, however, further research is required to confirm these findings and provide more information on long-term effects. (2007) P

- There is no consistent evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy or electrostimulation are effective for smoking cessation, but methodological problems mean that no firm conclusions can be drawn. Further research using frequent or continuous stimulation is justified. (2006) N/P

- Acupuncture is not superior to sham treatment for recovery in activities of daily living and health-related quality of life after stroke, although there may be a limited effect on leg function in more severely affected patients. (2005) N

- The evidence from controlled trials is insufficient to conclude whether acupuncture is an effective treatment for depression, but justifies further trials of electroacupuncture. (2005) N

- Acupuncture effectively relieves chronic low back pain. No evidence suggests that acupuncture is more effective than other active therapies. (2005) N/P

- In view of the small number of studies and their variable quality, doubt remains about the effectiveness of acupuncture for gynaecological conditions. Acupuncture and acupressure appear promising for dysmenorrhoea, and acupuncture for infertility, and further studies are justified. (2003) N

- In conclusion, the results suggest that the procedure using the new device is indistinguishable from the same procedure using real needles in acupuncture naïve subjects, and is inactive, where the specific needle sensation (de qi) is taken as a surrogate measure of activity. It is therefore a valid control for acupuncture trials. The findings also lend support to the existence of de qi, a major concept underlying traditional Chinese acupuncture. (2002) N/P

- There is no clear evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy or electrostimulation are effective for smoking cessation. (2002) N

- Collectively, these data imply that acupuncture is superior to various control interventions, although there is insufficient evidence to state whether it is superior to placebo. (2002) N/P

- In conclusion, the incidence of adverse events following acupuncture performed by doctors and physiotherapists can be classified as minimal; some avoidable events do occur. Acupuncture seems, in skilled hands, one of the safer forms of medical intervention. (2001) N/P

- Based on the evidence of rigorous randomised controlled trials, there is no compelling evidence to show that acupuncture is effective in stroke rehabilitation. Further, better-designed studies are warranted. (2001) N

- Although it has already been demonstrated that severe adverse events seem to be uncommon in standard practice, many serious cases of negligence have been found in the present review, suggesting that training system for acupuncturists (including medical doctors) should be improved and that unsupervised self-treatment should be discouraged. (2001) N

- Direct needling of myofascial trigger points appears to be an effective treatment, but the hypothesis that needling therapies have efficacy beyond placebo is neither supported nor refuted by the evidence from clinical trials. Any effect of these therapies is likely because of the needle or placebo rather than the injection of either saline or active drug. Controlled trials are needed to investigate whether needling has an effect beyond placebo on myofascial trigger point pain. (2001) N/P

- Although the incidence of minor adverse events associated with acupuncture may be considerable, serious adverse events are rare. Those responsible for establishing competence in acupuncture should consider how to reduce these risks. (2001) N

- In conclusion, this study does not provide evidence that this form of acupuncture is effective in the prevention of episodic tension-type headache. (2000) N

- The present study provides no strong evidence to support the hypothesis that the acupuncture point SP6 is more tender in women and in men. Recommendations for further investigations are discussed. (2000) N

- Acupuncture has not been demonstrated to be efficacious as a treatment for tinnitus on the evidence of rigorous randomized controlled trials. (2000) N

- We conclude that acupuncture continues to be associated with occasional, serious adverse events and fatalities. These events have no geographical limits. Most of these events are due to negligence. Everyone concerned with setting standards, delivering training, and maintaining competence in acupuncture should familiarise themselves with the lessons to be learnt from these untoward events. (2000) N

- Overall, the existing evidence suggests that acupuncture has a role in the treatment of recurrent headaches. However, the quality and amount of evidence is not fully convincing. There is urgent need for well-planned, large-scale studies to assess effectiveness and efficiency of acupuncture under real life conditions. (1999) N/P

- While the frequency of adverse effects of acupuncture is unknown and they may be rare, knowledge of normal anatomy and anatomical variations is essential for safe practice and should be reviewed by regulatory bodies and those responsible for training courses. (1999) N

- In conclusion, the hypothesis that acupuncture is efficacious in the treatment of neck pain is not based on the available evidence from sound clinical trials. Further studies are justified. (1999) N

- Even though all studies are in accordance with the notion that acupuncture is effective for temporomandibular joint dysfunction, this hypothesis requires confirmation through more rigorous investigations. (1999) N

- Acupuncture is not free of risks. All adverse events reported in 1997 would have been avoidable. The absolute number of cases is small, but the degree of underreporting remains unknown. (1999) N

- This form of electroacupuncture is no more effective than placebo in reducing nicotine withdrawal symptoms. (1998) N

- Acupuncture was shown to be superior to various control interventions, although there is insufficient evidence to state whether it is superior to placebo. (1998) N/P

- Considerable variation was observed in the scores awarded by the acupuncture experts. (1998) N

- It is therefore concluded that, according to the data published to date, the evidence that acupuncture is a useful adjunct for stroke rehabilitation is encouraging but not compelling. More and better trials are required to clarify this highly relevant issue. (1996) N

The results are remarkable (particularly considering that one would not expect unbiased studies or reviews of acupuncture to generate plenty of positive conclusions):

0 times N, 5 times N/P, 22 times P – after Adrian had left my department,

17 times N, 7 times N/P, 0 times P – while Adrian worked in my department.

From these figures, it is tempting to calculate the ratios for both periods of negative : positive conclusions:

zero versus infinite

If that is not impressive, I don’t know what is!

Looking just at the positive and the negative papers over the years:

One could discuss these papers in more detail, but I think this is hardly necessary. Just a few highlights perhaps: look at articles No 5, 20 and 27 for examples of turning an essentially negative finding into a positive conclusion. Notice that Adrian conducted a clinical trial of acupuncture for smoking cessation (No 49) while working with me and later published uncritical positive reviews on the subject. Does this not indicate that he distrusted his own study because it had not generated the result he had hoped for?

One could discuss these papers in more detail, but I think this is hardly necessary. Just a few highlights perhaps: look at articles No 5, 20 and 27 for examples of turning an essentially negative finding into a positive conclusion. Notice that Adrian conducted a clinical trial of acupuncture for smoking cessation (No 49) while working with me and later published uncritical positive reviews on the subject. Does this not indicate that he distrusted his own study because it had not generated the result he had hoped for?

Of course, my analysis is merely a case study and therefore my findings are not generalisable. However, in my personal experience, the described phenomenon is by no means an exception in SCAM research. I have observed similar phenomena over and over again. Just look at the ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME that I created for this blog:

- John Weeks (editor of JCAM)

- Deepak Chopra (US entrepreneur)

- Cheryl Hawk (US chiropractor)

- David Peters (osteopathy, homeopathy, UK)

- Nicola Robinson (TCM, UK)

- Peter Fisher (homeopathy, UK)

- Simon Mills (herbal medicine, UK)

- Gustav Dobos (various, Germany)

- Claudia Witt (homeopathy, Germany and Switzerland)

- George Lewith (acupuncture, UK)

- John Licciardone (osteopathy, US)

But Adrian’s case might be unique because it allows us to make a longitudinal observation over two decades. And it suggests to me that an ideological bias can (and often is) so strong and indistructable that is re-emerges as soon as it is no longer kept under strict control.

I have long suspected that ideological conflicts of interest have a much more powerful influence in SCAM research than financial ones. Such an overpowering influence might even be characteristic to much of SCAM research. And because it can be so dominant, it seems important to know about. People reading research need to be aware that it originates from a biased source, and funders who finance research would be wise to think twice about supporting researchers who are likely to generate findings that are biased and therefore false-positive. In the final analysis, such research is worse than no research at all.

Today is the day to admit it: we all owe a big THANKS to the worldwide homeopathy community. We should be most grateful to them all for selflessly demonstrating so indisputably something of fundamental importance:

homeopaths do not believe in their own outlandish, science-defying assumptions.

Yes, I really do appreciate the courage and altruism that was required for this epoch-making step!

Perhaps I better explain.

On 10 November, I issued ‘a challenge for all homeopaths of the world‘.

The deal was structured around a homeopathic proving (or, if you wish, around the assumption that highly diluted homeopathic remedies can have any noticable effects) and went as follows:

- you, the convinced homeopath, name the 6 homeopathic remedies that you cannot possibly miss when doing a proving on yourself;

- I order them in the potency you wish (only condition: it must be higher than C12) from a reputable source;

- I have the bottles delivered unopened to a notary where I live;

- the notary fills them into containers marked 1-6 (if you wish, you can send the notary empty containers for that ppurpose);

- the notary keeps the code under lock and key that links the name of the remedies to the numbers 1-6;

- he then mails the coded 6 remedies to you;

- you can use the proving method which you consider best and do as many provings as you like (the only limiting factors are the number of globuli in the containers and the time you have to crack the code);

- I give you 100 days for conducting the provings;

- once you are ready, you send your verdicts to the notary (e.g. 1 = rhus, tox, 2 = sulfur, 3 = arsenic, etc., etc.);

- the notary looks up the code and lets us both know the result.

I am happy to pay all the costs involved in the experiment (notary, remedies, postage, etc.). We can also discuss some of the details of this challenge, in case they run counter to your views on provings, rigorous science, etc.

To make sure we both ‘mean business’, once we both accept these conditions (you can flesh out the missing details as you wish), we both transfer a sum Euro 2 000 to an account with the notary. If you want to increase the sum, please let me know; as I said, we can discuss most of the details of my challenge to suit your needs. If you manage to ‘crack the code’ 1-6, the notary will transfer the sum of Euro 4 000 (your deposit and mine) to your account. If you fail, he will transfer the same amount to my account.

__________________________________________

In my original post, I made it abundantly clear that the entry to the challenge would close at the end of 2020. While it was still open, I did everything I could to let homeopaths know about the challenge. Because homeopathy originated in Germany and is still fairly popular there, I even re-published my challenge in German. In addition, I and others tweeted many times about it (in English, German, French, Spanish and possibly other languages as well), even directly to homeopaths across the globe.

As no homeopath has come forward to take up the challenge in time, and as no sound argument has emerged to convince me that my challenge was unreasonable, unscientific or unfair, it now is an indisputable fact that:

homeopaths do not believe in their own outlandish, science-defying assumptions.

I am most grateful to the worldwide community of homeopaths for heroically documenting the truth so clearly. It can’t have been easy to be so honest at the cost of homeopathy’s reputation. But I believe that this is an important and honourable step into the right direction. It provides essential information for non-homeopaths who want to understand the practice and profession of homeopathy.

MANY THANKS AGAIN

PS

In the interest of progress, please publicise the news as widely as you can.

2020 was certainly a difficult year (please note, I am trying a British understatement here). From the point of view of running this blog, it was sad to lose James Randi (1928 – 2020) who had been the hero of so many sceptics worldwide, and to learn of the passing of Frank Odds (1945-2020) who was a regular, thoughtful commentator here.

Reviewing the topics we tackled, I could mention dozens. But let me pick out just a few themes that I feel might be important.

HOMEOPATHY

Homeopathy continued to have a rough time; the German medical profession has finally realised that homeopathy is treatment with placebos and the German Green Party no longer backs homeopathy. In India, the Supreme Court ruled: Homeopathy must not be sold as a cure of Covid-19, and in the US improved labeling on homeopathic products were introduced. To make matters worse I issued A CHALLENGE FOR ALL HOMEOPATHS OF THE WORLD.

NOVEL SCAMs

On this blog, I like to write about new so-called alternative medicines (SCAMs) that I come accross. Blood letting is not exactly new, but Oh look! Bloodletting is back! Many other ‘innovations’ were equally noteworthy. Here is merely a very short selection of modalities that were new to me:

- Hydrogen-rich water: the new wonder drug?

- Dr. Robin A. Bernhoft and his ‘Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy’ (BHRT)

- The ‘OBERON’: revolutionary invention or dangerous con?

- Qi technology: “scientifically proven to provide EMF Protection” (edzardernst.com)

- ‘DRX9000’ for back pain: a nice little earner for chiropractors and other back pain quacks

- Vibroacoustic Sound Therapy: introducing the ‘healthy vibration of cells’ into the body

- Lakhovsky’s oscillator, the ‘cure all’ that the world forgot

COVID-19

Unquestionably the BIG subject (not just) in SCAM was – is and will be for a while – the pandemic. It prompted quacks of any type to crawl out of the woodwork misleading the public about their offerings. On 24 January, I wrote for the first time about it: Coronavirus epidemic: Why don’t they ask the homeopaths for help? Thereafter, every charlatan seemed to jump on the COVID bandwaggon, even Trump: Trump seems to think that UV might be the answer to the corona-pandemic – could he mean “ultraviolet blood irradiation”? It became difficult to decide who was making a greater fool of themselves, Trump or the homeopaths (Is this the crown of the Corona-idiocy? Nosodes In Prevention And Management Of COVID -19). Few SCAM entrepreneurs (Eight new products aimed at mitigating COVID-19. But do they really work?) were able to resist the opportunity. Snakeoil salesmen were out in force and view COVID-19 as an ‘opportunity’. It is impossible to calculate what impact all this COVID-quackery had, but I fear that many people lost their lives at least in part because of it.

VACCINATION

The unavoidable consequence of the pandemic was that the anti-vaxx brigade sensed that their moment had arrived. Ex-doctor Andrew Wakefield: “Better to die as a free man than live as a slave” (and get vaccinated against Covid-19). Again the ‘charlatan in chief’ made his influence felt through the ‘Trump-Effect’ on vaccination attitudes. Unsurprisingly, the UK ‘Society of Homeopath’ turned out to be an anti-vaxx hub that endangers public health. And where there is anti-vaxx, chiropractors are seldom far: Ever wondered why so many chiropractors are profoundly anti-vax?. All this could be just amusing, but sadly it has the potential to cost lives through Vaccine hesitancy due to so-called alternative medicine (SCAM).

ETHICS

I happen to believe that ethics in SCAM are an important, yet much neglected topic. It is easy to understand why this should be so: adhering to the rules of medical ethics would all but put an end to SCAM. This applies to chiropractic (The lack of chiropractic ethics: “valid consent was not obtained in a single case”), to homeopaths (Ethical homeopathy) and to most other SCAM professions. If I had a wish for the next year(s), it would be that funding agencies focus on research into the many ethical problems posed by the current popularity of SCAM.

CONCLUSION

If I had another wish, it would be that critical thinking becomes a key subject in schools, universities and adult education. Why do so many people make irrational choices? One answer to this question is, because we fail to give this subject the importance it demands. The lack of critical thinking is the reason why we elect leaders who are compulsory lyers, make wrong choices about healthcare, and continue to destroy the planet as though there is no tomorrow. It is high time that we, as a society, realise how fundamentally important critical thinking truly is.

OUTLOOK

Yes, 2020 was difficult: Brexit, COVID-19, anti-vaxx, etc. But it was not all bad (certainly not for me personally), and there is good reason for hope: the globally malign influence of Trump is about to disappear, and we now have several effective vaccines. Common sense, decency and science might triumph after all.

HEALTHY NEW YEAR EVERYONE!

I often hear that my ambitions to inform the public and inspire critical thinking are hopeless: there are simply too many quacks trumpeting nonsense, and their collective influence is surely bigger than mine. This can be depressing, of course. And because I often feel that I am fighting an unwinnable battle, stories like this are so importand and up-lifting.

Denby Royal was a ‘holistic nutritionist’, then she became a critic of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Here is the story about her transformation:

… I had gone to holistic nutrition school. I was running my own nutrition consulting business. And suddenly I didn’t believe in any of it anymore. How did this flip flop come to pass?

… As a holistic nutritionist, I was an active participant in what I now consider alternative medicine tomfoolery, specifically pushing supplements on a clientele of the “worried well” who often mistook wellness enthusiasts like me for medical experts. I want to be clear that I wasn’t knowingly deceiving anyone—I really did believe in the solutions I was offering my clients… To holistic nutrition enthusiasts and people who believe in a certain kind of alt wellness, these “natural” and “holistic” products seem more trustworthy than what mainstream medicine offers. The truth is, they often lack sufficient, peer-reviewed, reliable scientific evidence of their supposed effectiveness.

Did I have rock-solid evidence that these products would do what their labels promised they would do? Not really. Sure, I read studies here and there that found specific health benefits for some of the products. But I rarely mentioned the fine print (if I knew it at all)—that the sample sizes of many of these studies often were so small that the results couldn’t be generalized to a larger population, that the studies’ authors sometimes noted that more research was needed to support any findings on the effects they found, or that systematic reviews later found that many studies were poorly constructed or at risk for bias, making their findings even less compelling than they seemed initially. And in some cases, study authors themselves note that their findings are merely jumping off points, and that more long-term studies are needed in order to draw more solid conclusions…

Was I relying on strong, valid evidence? Nah, not really. But at the time, I thought what I had was better than strong evidence: Faith in a lifestyle and a dogmatic belief that all things traditional and mainstream were unhealthy or harmful, and therefore, that all things unconventional and alternative were curative and would bring about “wellness.”

In an effort to expand my product knowledge I researched a lot of the different supplements available. I was using all the best bias-confirming websites where other homeopathic medicine enthusiasts evangelized their favorite remedies, their enthusiasm and insistence, and anecdotal evidence standing in for what typically shows us that a product is safe and effective—clinical trials and FDA approval.

When their arguments and reasoning started to sink in, I realized that my faith in the healing powers of supplements may have been overzealous at best, unfounded at worst. My world crumbled like a piece of raw gluten-free paleo cheesecake. It started to sink in: Where there was a morsel of convincing medical information blended with enough compelling nonsense and communicated with enough conviction, I believed it, hook, line, and sinker.

When I started to notice the holes in the fabric of holistic nutrition, the fabric looked, well, pretty threadbare. I subsequently disconnected from social media and distanced myself from the entire culture. I took a good look at how I was personally and publicly communicating my relationships with food and wellness. After spending my twenties experimenting with all kinds of specialty diets, I was left feeling exhausted, anxious, underweight, overweight, and fed-up.

And so that last domino fell when I took away the thing that was propping it up for me: social media. Instagram is a playground for wellness influencers, including, at the time, me. My Instagram account was the best way to advertise my nutrition consulting business, so maintaining a certain persona there felt completely crucial to my success, and eventually, my identity. It was a world full of beautifully curated accounts of thin yogis gathering wild herbs in nature or making raw desserts with ingredients that cost more than my entire monthly food budget. I started to feel like the alternative wellness community I was part of—myself included—was an echo chamber, where we stockpiled likes and positive comments to build a wall that would keep out ideas that challenged our status quo. In fact, the more reassurance I received from my online community, the harder I believed in our gospel.

As I was disentangling my beliefs from everything I was learning by looking at the actual evidence, I realized that my education to become a holistic nutritionist hadn’t prepared me to understand health and wellness as completely and comprehensively as I’d once thought. Sure, I’d spent a some time studying the pathology of disease, and a little longer learning about how each bodily system works to get your human suit from point A to point B, but I am only slightly closer to being a medical professional than I am to becoming a professional cricket player. First of all, in total, my entire formal education as a holistic nutritionist was 10 months long. Second of all, that education was intended to complement—not replace—traditional medical treatment. But as soon as I finished the program, I could immediately start taking on clients. And lots of potential clients out there are just like the way I used to be—wishing they looked or felt different and in search of the panacea, willing (if not eager) to defer to an expert.

There may have been many people willing to look to me as an expert, but here’s the thing: in my school, there were no residency or clinical hours required to prepare us for the real world or to take on clients—unlike dietitians here in Canada, who must obtain a bachelor’s degree in Nutritional and Food Sciences, qualify to complete a rigorous post-degree internship program and register with a provincial dietetics organization, or get a master’s degree. We received a certificate, and that was that. It was a credential that wholeheartedly fell short of resembling anything close to making me an authority on the subject of health as it relates to food and diet. But most people in the general public can’t be expected to understand the ins and outs of how experts are credentialed and licensed—many of us assume that someone calling themselves something that we associate with authority is, in fact, an authority we can trust.

The brief education that I received to become a holistic nutritionist did provide me with valuable stepping stones and a general understanding of how the body works. My program discouraged students from saying “treat,” “heal,” “prevent,” or “cure.” Generally speaking holistic nutrition programs don’t provide the training and medical education that registered dietitians receive, which enables them to give sound, ethical medical nutrition advice, nor are they required by law, the way dietitian programs are, to provide it. In fact, in 2015 graduates of the Canadian School of Natural Nutrition were barred from identifying as Registered Holistic Nutritionists, and since then must use the title “Holistic Nutritional Consultant.”

… With what I do have from my classroom education, I can analyze a lifestyle that needs some fine-tuning and provide guidance on how to structure a solid meal plan. That’s about it. After years of self-diagnosis and hashtagging all my fad-diet escapades (for this, I greatly apologize to all those I have alienated with my profuse self-righteousness), I can at least say I have a deep appreciation for those who are actually on the front lines in the fight against unproven medical remedies and the potential damage it may do to those who use it to the exclusion of traditional medicine.

The influence of these remedies is not harmless, and I have seen firsthand in many different examples and situations how it can lure people away from real, evidence-based help in their times of need. I am fortunate enough that within my practice I had enough foresight to turn away individuals who required more guidance than I was capable of giving. But along the way I made many embarrassing and conjectural recommendations. Like I said, I was far from knowingly deceiving anyone. I firmly held the belief that alternative medicine, no matter the cost, was an investment in a healthful future. My own medicine cabinet, an arsenal full of supplements, tincture, and powders, was a personal testament to how deeply I was devoted to holistic nutrition.

This essay is a firm farewell from a world I disconnected from long ago. The person that over years I let myself become through naiveté, not doing my own research, and a misguided desire to be different. So here I am now, officially having left the church of woo, bidding the world of alternative health adieu.

_________________________________

Reading Denby’s account, I was reminded of many themes we have previously discussed on this blog. One issue that perhaps needs more focus is this notion:

“I was far from knowingly deceiving anyone.”

I have not yet met a SCAM practitioner who says:

“I am in the business of deceiving my patients.”

The reasons for this are simple:

- if they knowingly deceive, they would not tell us,

- and if they don’t know that they are deciving their patients, they cannot possibly admit to it.

The way Denby repeatedly assures us that she was far from knowingly deceiving anyone sounds charmingly naive and is, in my experience, very typical for SCAM practitioners. It depicts them as honorable people. Yet, in actual fact, it is neither charming nor honorable. It merely demonstrates the fact that they were perhaps not ruthlessly dishonest but all the more dangerous.

Let me explain this with a deliberately extreme example:

- A man with a chronic condition – say type 2 diabetes – consults a SCAM practitioner who is knowingly deceiving him claiming that her SCAM effectively treats his condition. The patient follows the advice but, since he is not totally convinced (deception is rarely perfect), consults his doctor who puts him straight. This patient will therefore survive.

- The same chap consults a SCAM practitioner who is deeply convinced of the effectiveness of her SCAM and thus not knowingly deceiving her patient when she claims that it is effective for his diabetes. Her conviction is so strong that the patient blindly believes her. Thus he stops his conventional medication and hopes for the best. This patient could easily die.

In a nutshell:

‘Honest’ conviction might render a quack more socially acceptable but also more dangerous to her patients.

There are of course 2 types of osteopaths: the US osteopaths who are very close to real doctors, and the osteopaths from all other countries who are practitioners of so-called alternative medicine. This post, as all my posts on this subject, is about the latter category.

I was alerted to a paper entitled ‘Osteopathy under scrutiny’. It goes without saying that I thought it relevant; after all, scrutinising so-called altermative medicine (SCAM), such as osteopathy is one of the aims of this blog. The article itself is in German, but it has an English abstract:

Osteopathic medicine is a medical specialty that enjoys a high level of recognition and increasing popularity among patients. High-quality education and training are essential to ensure good and safe patient treatment. At a superficial glance, osteopathy could be misunderstood as a myth; accurately considered, osteopathic medicine is grounded in medical and scientific knowledge and solid theoretical and practical training. Scientific advances increasingly confirm the empirical experience of osteopathy. Although more studies on its efficacy could be conducted, there is sufficient evidence for a reasonable application of osteopathy. Current scientific studies show how a manually executed osteopathic intervention can induce tissue and even cellular reactions. Because the body actively responds to environmental stimuli, osteopathic treatment is considered an active therapy. Osteopathic treatment is individually applied and patients are seen as an integrated entity. Because of its typical systemic view and scientific interpretation, osteopathic medicine is excellently suited for interdisciplinary cooperation. Further work on external evidence of osteopathy is being conducted, but there is enough knowledge from the other pillars of evidence-based medicine (EBM) to support the application of osteopathic treatment. Implementing careful, manual osteopathic examination and treatment has the potential to cut healthcare costs. To ensure quality, osteopathic societies should be intimately involved and integrated in the regulation of the education, training, and practice of osteopathic medicine.

This does not sound as though the authors know what scutiny is. In fact, the abstract reads like a white-wash of quackery. Why might this be so? To answer this question, we need to look no further than to the ‘conflicts of interest’ where the authors state (my translation): K. Dräger and R. Heller state that, in addition to their activities as further education officers/lecturers for osteopathy (Deutsche Ärztegesellschaft für Osteopathie e. V. (DÄGO) and the German Society for Osteopathic Medicine e. V. (DGOM)) there are no conflicts of interest.

But, to tell you the truth, the article itself is worse, much worse that the abstract. Allow me to show you a few quotes (all my [sometimes free] translations).

- Osteopathic medicine is a therapeutic method based on the scientific findings from medical research.

- [The osteopath makes] diagnostic and therapeutic movements with the hands for evaluating limitations of movement. Thereby, a blocked joint as well as a reduced hydrodynamic or vessel perfusion can be identified.

- The indications of osteopathy are comparable to those of general medicine. Osteopathy can be employed from the birth of a baby up to the palliative care of a dying patient.

- Biostatisticians have recognised the weaknesses of RCTs and meta-analyses, as they merely compare mean values of therapeutic effects, and experts advocate a further evidence level in which statictical correlation is abandonnened in favour of individual causality and definition of cause.

- In ostopathy, the weight of our clinical experience is more important that external evidence.

- Research of osteopathic medicine … the classic cause/effect evaluation cannot apply (in support of this statement, the authors cite a ‘letter to the editor‘ from 1904; I looked it up and found that it does in no way substantiate this claim)

- Findings from anatomy, embryology, physiology, biochemistry and biomechanics which, as natural sciences, have an inherent evidence, strengthen in many ways the plausibility of osteopathy.

- Even if the statistical proof of the effectiveness of neurocranial techniques has so far been delivered only in part, basic research demonstrates that the effects of traction or compression of bogily tissue causes cellular reactions and regulatory processes.

What to make of such statements? And what to think of the fact that nowhere in the entire paper even a hint of ‘scrutiny’ can be detected? I don’t know about you, but for me this paper reflects very badly on both the authors and on osteopathy as a whole. If you ask me, it is an odd mixture of cherry-picking the evidence, misunderstanding science, wishful thinking and pure, unadulterated bullshit.

You urgently need to book into a course of critical thinking, guys!

On this blog we have seen just about every variation of misdemeanors by practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM). Today, I will propose a scale and rank order of these lamentable behaviours. As we regularly discuss chiropractic and homeopathy here, I decided to use these two professions as examples (but I could, of course, have chosen almost any other SCAM).

- Treating conditions which are not indicated: SCAM practitioners of all types are often asked by their patients to treat conditions which their particular SCAM cannot not affect. Instead of honestly saying so, they frequently apply their SCAM, wait for the natural history of the condition to do its bit, and subsequently claim that their SCAM was effective.

- Over-charging: asking too much money for services or goods is common (not just) in SCAM. It raises the question, what is the right price? There is, of course, no easy answer to it. Over-charging is therefore mostly a judgement call and not something absolute.

- Misleading a patient: there are numerous ways in which patients can be misled by their SCAM practitioners. A chiropractor who uses the Dr title, without explaining that it is not a medical title, is misleading his/her patients. A homeopath who implies that the remedy he/she is selling is a proven treatment is also misleading his/her patients.

- Being economical with the truth: the line between lying (see below) and being economical with the truth is often blurred. In my view, a chiropractor who does not volunteer the information that acute back pain, in most cases, resolves within a few days regardless of whether he/she mapipulates the patient’s spine or not, is economical with the truth. Similarly, a homeopath who does not explain up front that the remedy he/she prescribes does not contain a single active molecule is economical with the truth.

- Employing unreasonably long series of therapy: A chiropractor or homeopath, who treats a patient for months without any improvement in the patient’s condition, should suggest to call it a day. Patients should be given a treatment plan at the first consultation which includes the information when it would be reasonable to stop the SCAM.

- Failing to refer: A chiropractor or homeopath, who treats a patient for months without any improvement in the patient’s condition should refer the patient to another, better suited healthcare provider. Failing to do so is a serious disservice to the patient.

- Unethical behaviour: there are numerous ways SCAM practitioners regularly violate healthcare ethics. The most obvious one, as discussed often before on this blog, is to cut corners around informed consent. A chiropractor might, for instance, not tell his/her patient before sarting the treatment that spinal manipulation is not supported by sound evidence for efficacy or safety. A homeopathy might not explain that homeopathy is generally considered to be implausible and not evidence-based.

- Neglect: medical neglect occurs when patients are harmed or placed at significant risk of harm by gaps in their medical care. If a chiropractor or a homeopath, for instance, claim to be able to effectively treat asthma and fail to insist that all prescribed asthma medications must nevertheless be continued – as both often do – they are guilty of neglect, in my view. Medical neglect can be a reason for starting legal proceedings.

- Lying: knowingly not telling the truth can also be a serious legal issue. An example would be a chiropractor who, after beeing asked by a patient whether neck manipulation can cause harm, answers that it is an entirely safe procedure which has never injured anyone. Similarly, if a homeopaths informs his/her patient that the remedy he/she is prescribing has been extensively tested and found to be effective for the patient’s condition, he must be lying. If these practitioners believe what they tell the patient to be true, they might not technically be lying, but they would be neglecting their ethical duty to be adequately informed and they would therefore present an even greater danger to thier patients.

- Abuse: means to use something for the wrong purpose in a way that is harmful or morally wrong. A chiropractor who tells the mother of a healty child that they need maintenance care in order to prevent them falling ill in the future is abusing her and the child, in my view. Equally, I think that a homeopath, who homeopathically treats a disease that would otherwise be curable with conventional treatments, abuses his patient.

- Fraud: fraud is a legal term referring to dishonest acts that intentionally use deception to illegally deprive another person or entity of money, property, or legal rights. It relies on the use of intentional misrepresentation of fact to accomplish the taking. Arguably, most of the examples listed above are fraud by this definition.

- Sexual misconduct: the term refers to any behaviour which is sexual in nature and which is unwelcome and engaged in without consent. It ranges from unwanted groping to rape. There is, for instance, evidence that sexual misconduct is not a rarety in the realm of chiropractic. I have personally served once as an expert witness against a SCAM practitioner is a court case at the Exeter Crown Court.

The 12 categories listed above are not nearly as clearly defined as one would wish, and there is plenty of overlap. I am not claiming that my suggested ‘scale of misdemeanors by SCAM practitioners‘ or the proposed rank order are as yet optimal or even adequate. I am, however, hoping that readers will help me with their suggestions to improve them. Perhaps your input might then generate a scale of practical use for the future.

In so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) – but certainly not just there – we regularly encouter reports about new research results that sound odd, implausible, too good to be true, or outright fantastic (like borne out of fantasy). What should one do with such news? Keep an open mind, yes sure, but what if the news leads us up the garden path? Here is what I usually do and what I recommend you might do as well:

- Check who published the story; some sources are clearly more trustworthy than others (think of ‘Natural News‘, or WDDTY, for instance).

- Try to find other outlets confirming the news; if none can be located, be extra sceptical.

- Identify the origin of the new research; an academic might be more trustworthy that a SCAM practitioner or a commercial firm.

- Find out where the study was originally published; some SCAM journals publish virtually any rubbish (think of EBCAM or JCAM).

- If you are still in doubt and continue to be interested, go on Medline and obtain the original article.

- If it’s behind a pay-wall, email the authors for a copy.

- Check the validity of the paper; this can be rather a big task for someone not trained in critical assessment of scientific papers, but there are certain pointers: in case of a clinical trial, for instance, check whether it was large or small, randomised or not, placebo-controlled or not, blind or not.

- If the findings look suspicious to you, find out more about the researchers: for example, do they have a track record of publishing results that look false-positive (think of M Frass or other members of the ‘ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE HALL OF FAME‘, for instance)?

- Identify studies by other researchers addressing the same research question; have similar findings been published, or do most of the previous investigations contradict the results of the new study?

- Find out who sponsored the new study.

- Look up what the authors declare in terms of conflicts of interest.

- If all of this leaves important questions unanswered, don’t be shy, write to the authors and ask.

When I have gone through all these steps, I usually have a fairly clear impression whether I can trust the research or not. Obviously keeping an open mind about new discoveries is sensible. But please. do remember that charlatans might (and often do) put a lot of BS in your mind, if you open it too wide for too long.