bogus claims

The pandemic has shown how difficult it can be to pass laws stopping healthcare professionals from giving unsound medical advice has proved challenging. The right to freedom of speech regularly conflicts with the duty to protect the public. How can a government best sail between Scylla and Charybdis? JAMA has just published an interesting paper addressing these issues. Here is an excerpt from the article that might stimulate some discussion:

The government can take several actions, including:

- Imposing sanctions on COVID-19–related practices by licensed professionals that flout substantive laws in connection with providing medical services, even if those medical services include speech. This includes physicians failing to comply with COVID-19–related public health laws applicable to medical offices and health facilities, such as mask wearing, social distancing, and restrictions on elective procedures.

- Sanctioning recommendations by professionals that patients take illegal medications or controlled substances without following legally required procedures. The government can also sanction the marketing by others of prescription medications for unapproved indications. However, “off-label” prescribing by physicians (eg, for hydroxychloroquine or ivermectin) remains lawful as long as a medication is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for any indication and no specific legal conditions on use are in effect.

- Enforcing tort law actions (eg, malpractice, lack of informed consent) in cases of alleged patient injury that result from recommending a potentially dangerous treatment or failing to recommend a necessary treatment.

- Imposing sanctions on individualized medical advice by unlicensed individuals or organizations if giving that advice constitutes the unlawful practice of medicine.

In addition, the government probably can:

- Impose sanctions for false or misleading information offered to obtain a financial or personal benefit, particularly if giving the information constitutes fraud under applicable law. This would encompass physicians who knowingly spread false information to create celebrity or attract patients.

- Threaten disciplinary action by licensing boards against health professionals whose speech to patients conveys incorrect science or substandard medicine.

- Specify the information that may and may not be imparted by private organizations and professionals as part of specific clinical services paid for by government, such as special programs for COVID-19 testing or treatment.

- Reject legal challenges to, and enforce through generally applicable contract or employment laws, any restrictions private health care organizations place on speech by affiliated health professionals, particularly in the absence of special laws conferring “conscience” protections. This would include medical staff membership and privileges, hospital or other employment agreements, and insurance network participation.

- Enforce restrictions on speech adopted by private professional or self-regulatory organizations if the consequences for violations are limited to revoking organizational membership or accreditation.

However, the government probably cannot:

- Compel or limit health professional speech not made in connection with patient care, even if the speech is false or misleading, regardless of its alleged effect on public trust in health professions.

- Sanction speech to the general public rather than to patients, whether or not by health professionals, especially if conveyed with a disclaimer that the speech is “not intended as medical advice.”

- Sanction speech by health professionals to patients conveying political views or skepticism of government policy.

- Enforce restrictions involving information by public universities and public hospitals that legislatures, regulatory agencies, and professional licensing boards would not be constitutionally permitted to impose directly.

- Adopt restrictions on information related to overall clinical services funded by large government health programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

_____________________________

The article was obviously written with MDs in mind and applies only to US law. As we have seen in previous posts and comments, the debate is, however, wider. We should, I think, also have it in relation to practitioners of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) and medical ethics. Moreover, it should go beyond advice about COVID and be extended to any medical advice given by any type of healthcare practitioner.

No 10-year follow-up study of so-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (LDH) has so far been published. Therefore, the authors of this paper performed a prospective 10-year follow-up study on the integrated treatment of LDH in Korea.

One hundred and fifty patients from the baseline study, who initially met the LDH diagnostic criteria with a chief complaint of radiating pain and received integrated treatment, were recruited for this follow-up study. The 10-year follow-up was conducted from February 2018 to March 2018 on pain, disability, satisfaction, quality of life, and changes in a herniated disc, muscles, and fat through magnetic resonance imaging.

Sixty-five patients were included in this follow-up study. Visual analogue scale score for lower back pain and radiating leg pain were maintained at a significantly lower level than the baseline level. Significant improvements in Oswestry disability index and quality of life were consistently present. MRI confirmed that disc herniation size was reduced over the 10-year follow-up. In total, 95.38% of the patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the treatment outcomes and 89.23% of the patients claimed their condition “improved” or “highly improved” at the 10-year follow-up.

The authors concluded that the reduced pain and improved disability was maintained over 10 years in patients with LDH who were treated with nonsurgical Korean medical treatment 10 years ago. Nonsurgical traditional Korean medical treatment for LDH produced beneficial long-term effects, but future large-scale randomized controlled trials for LDH are needed.

This study and its conclusion beg several questions:

WHAT DID THE SCAM CONSIST OF?

The answer is not provided in the paper; instead, the authors refer to 3 previous articles where they claim to have published the treatment schedule:

The treatment package included herbal medicine, acupuncture, bee venom pharmacopuncture and Chuna therapy (Korean spinal manipulation). Treatment was conducted once a week for 24 weeks, except herbal medication which was taken twice daily for 24 weeks; (1) Acupuncture: frequently used acupoints (BL23, BL24, BL25, BL31, BL32, BL33, BL34, BL40, BL60, GB30, GV3 and GV4)10 ,11 and the site of pain were selected and the needles were left in situ for 20 min. Sterilised disposable needles (stainless steel, 0.30×40 mm, Dong Bang Acupuncture Co., Korea) were used; (2) Chuna therapy12 ,13: Chuna is a Korean spinal manipulation that includes high-velocity, low-amplitude thrusts to spinal joints slightly beyond the passive range of motion for spinal mobilisation, and manual force to joints within the passive range; (3) Bee venom pharmacopuncture14: 0.5–1 cc of diluted bee venom solution (saline: bee venom ratio, 1000:1) was injected into 4–5 acupoints around the lumbar spine area to a total amount of 1 cc using disposable injection needles (CPL, 1 cc, 26G×1.5 syringe, Shinchang medical Co., Korea); (4) Herbal medicine was taken twice a day in dry powder (2 g) and water extracted decoction form (120 mL) (Ostericum koreanum, Eucommia ulmoides, Acanthopanax sessiliflorus, Achyranthes bidentata, Psoralea corylifolia, Peucedanum japonicum, Cibotium barometz, Lycium chinense, Boschniakia rossica, Cuscuta chinensis and Atractylodes japonica). These herbs were selected from herbs frequently prescribed for LBP (or nerve root pain) treatment in Korean medicine and traditional Chinese medicine,15 and the prescription was further developed through clinical practice at Jaseng Hospital of Korean Medicine.9 In addition, recent investigations report that compounds of C. barometz inhibit osteoclast formation in vitro16 and A. japonica extracts protect osteoblast cells from oxidative stress.17 E. ulmoides has been reported to have osteoclast inhibitive,18 osteoblast-like cell proliferative and bone mineral density enhancing effects.19 Patients were given instructions by their physician at treatment sessions to remain active and continue with daily activities while not aggravating pre-existing symptoms. Also, ample information about the favourable prognosis and encouragement for non-surgical treatment was given.

The traditional Korean spinal manipulations used (‘Chuna therapy’ – the references provided for it do NOT refer to this specific way of manipulation) seemed interesting, I thought. Here is an explanation from an unrelated paper:

Chuna, which is a traditional manual therapy practiced by Korean medicine doctors, has been applied to various diseases in Korea. Chuna manual therapy (CMT) is a technique that uses the hand, other parts of the doctor’s body or other supplementary devices such as a table to restore the normal function and structure of pathological somatic tissues by mobilization and manipulation. CMT includes various techniques such as thrust, mobilization, distraction of the spine and joints, and soft tissue release. These techniques were developed by combining aspects of Chinese Tuina, chiropratic, and osteopathic medicine.[13] It has been actively growing in Korea, academically and clinically, since the establishment of the Chuna Society (the Korean Society of Chuna Manual Medicine for Spine and Nerves, KSCMM) in 1991.[14] Recently, Chuna has had its effects nationally recognized and was included in the Korean national health insurance in March 2019.[15]

This almost answers the other questions I had. Almost, but not quite. Here are two more:

- The authors conclude that the SCAM produced beneficial long-term effects. But isn’t it much more likely that the outcomes their uncontrolled observations describe are purely or at least mostly a reflection of the natural history of lumbar disc herniation?

- If I remember correctly, I learned a long time ago in medical school that spinal manipulation is contraindicated in lumbar disc herniation. If that is so, the results might have been better, if the patients of this study had not received any SCAM at all. In other words, are the results perhaps due to firstly the natural history of the condition and secondly to the detrimental effects of the SCAM the investigators applied?

If I am correct, this would then be the 4th article reporting the findings of a SCAM intervention that aggravated lumbar disc herniation.

PS

I know that this is a mere hypothesis but it is at least as plausible as the conclusion drawn by the authors.

Ginseng plants belong to the genus Panax and include:

- Panax ginseng (Korean ginseng),

- Panax notoginseng (South China ginseng),

- and Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng).

They are said to have a range of therapeutic activities, some of which could render ginseng a potential therapy for viral or post-viral infections. Ginseng has therefore been used to treat fatigue in various patient groups and conditions. But does it work for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also often called myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)? This condition is a complex, little-understood, and often disabling chronic illness for which no curative or definitive therapy has yet been identified.

This systematic review aimed to assess the current state of evidence regarding ginseng for CFS. Multiple databases were searched from inception to October 2020. All data was extracted independently and in duplicates. Outcomes of interest included the effectiveness and safety of ginseng in patients with CFS.

A total of two studies enrolling 68 patients were deemed eligible: one randomized clinical trial and one prospective observational study. The certainty of evidence in the effectiveness outcome was low and moderate in both studies, while the safety evidence was very low as reported from one study.

The authors concluded that the study findings highlight a potential benefit of ginseng therapy in the treatment of CFS. However, we are not able to draw firm conclusions due to limited clinical studies. The paucity of data warrants limited confidence. There is a need for future rigorous studies to provide further evidence.

To get a feeling of how good or bad the evidence truly is, we must of course look at the primary studies.

The prospective observational study turns out to be a mere survey of patients using all sorts of treatments. It included 155 subjects who provided information on fatigue and treatments at baseline and follow-up. Of these subjects, 87% were female and 79% were middle-aged. The median duration of fatigue was 6.7 years. The percentage of users who found a treatment helpful was greatest for coenzyme Q10 (69% of 13 subjects), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (65% of 17 subjects), and ginseng (56% of 18 subjects). Treatments at 6 months that predicted subsequent fatigue improvement were vitamins (p = .08), vigorous exercise (p = .09), and yoga (p = .002). Magnesium (p = .002) and support groups (p = .06) were strongly associated with fatigue worsening from 6 months to 2 years. Yoga appeared to be most effective for subjects who did not have unclear thinking associated with fatigue.

The second study investigated the effect of Korean Red Ginseng (KRG) on chronic fatigue (CF) by various measurements and objective indicators. Participants were randomized to KRG or placebo group (1:1 ratio) and visited the hospital every 2 weeks while taking 3 g KRG or placebo for 6 weeks and followed up 4 weeks after the treatment. The fatigue visual analog score (VAS) declined significantly in each group, but there were no significant differences between the groups. The 2 groups also had no significant differences in the secondary outcome measurements and there were no adverse events. Sub-group analysis indicated that patients with initial fatigue VAS below 80 mm and older than 50 years had significantly greater reductions in the fatigue VAS if they used KRG rather than placebo. The authors concluded that KRG did not show absolute anti-fatigue effect but provided the objective evidence of fatigue-related measurement and the therapeutic potential for middle-aged individuals with moderate fatigue.

I am at a loss in comprehending how the authors of the above-named review could speak of evidence for potential benefit. The evidence from the ‘observational study’ is largely irrelevant for deciding on the effectiveness of ginseng, and the second, more rigorous study fails to show that ginseng has an effect.

So, is ginseng a promising treatment for ME?

I doubt it.

Brite is an herbal energy drink that is currently being marketed aggressively. It is even for sale in one leading UK supermarket. It comes in various flavors the ingredients of which vary slightly.

The pineapple/mango drink, for instance, contains:

- guarana extract,

- green tea extract,

- guayusa extract,

- ashwagandha extract,

- matcha tea,

- ascorbic acid (vitamin C),

- natural caffeine.

The website of the manufacturer tells us that Brite uses ingredients and dosages that are safe and effective, utilising the power of nootropic superfoods organic Matcha, Guarana and Guayusa to provide a long-lasting boost.

Brite is based on peer reviewed, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials and studies that can be found here.

It does not tell us the dosages of the ingredients, and I am puzzled by the claim that the drink is safe. A quick search seems to cast considerable doubt on it.

_____________________________

Guarana (Paullinia cupana) is a plant from the Amazon region with a high content of bioactive compounds. It is by no means free of adverse effects. It is known to interact with:

- armodafinil

- caffeine

- dexmethylphenidate

- dextroamphetamine

- green tea

- lisdexamfetamine

- methamphetamine

- methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- methylphenidate

- modafinil

- phentermine

- yohimbine

And it can cause the following adverse effects:

- Abdominal spasms (from overdose)

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Convulsions

- Delirium

- Dependence

- Diarrhea

- Dizziness

- Fast heart rate

- Gastrointestinal (GI) upset

- Headache

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High blood sugar (hyperglycemia)

- Increased respiration

- Increased urination

- Insomnia

- Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias)

- Irritability

- Muscle spasms

- Nausea/vomiting

- Nervousness

- Painful urination (from overdose)

- Rapid breathing

- Restlessness

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Stomach cramps or irritation

- Tremors

- Withdrawal symptoms

Green tea is made from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant. It can cause the following adverse effects:

- headache,

- nervousness,

- sleep problems,

- vomiting,

- diarrhea,

- irritability,

- irregular heartbeat,

- tremor,

- heartburn,

- dizziness,

- ringing in the ears,

- convulsions,

- confusion.

Guayusa is a plant native to the Amazon rainforest that contains plenty of caffeine. Its adverse effects include:

- High Blood Pressure

- Rapid Heartbeat

- Anxiety

- Jitters

- Energy Crashes

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Upset Stomach

Ashwagandha is a plant from India; the root and berry are used in Ayurvedic medicine. Its adverse effects include:

- stomach upset,

- diarrhea,

- vomiting.

Matcha tea also contains a high amount of caffeine. It is associated with the following adverse effects:

- nervousness,

- irritability,

- dizziness,

- anxiety,

- digestive disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, or diarrhea,

- sleeping disorders,

- cardiac arrhythmia.

Caffeine is a chemical found in coffee, tea, cola, guarana, mate, and other products. Adverse effects include:

- insomnia,

- nervousness,

- restlessness,

- stomach irritation,

- nausea and vomiting,

- increased heart rate and respiration,

- headache,

- anxiety,

- agitation,

- chest pain,

- ringing in the ears.

A case report documented a case of myocardial infarction in a 25-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with chest pain. The patient had been consuming massive quantities of caffeinated energy drinks daily for the past week. This case report and previously documented studies support a possible connection between caffeinated energy drinks and myocardial infarction.

________________________

Yes, the adverse effects are predominantly (but not exclusively) caused by high doses. Yet, the claim that Brite is safe should nevertheless be taken with a very large pinch of salt. If I like the taste of the drink and thus consume a few bottles per day, the dosages of the ingredients would surely be high!

And what about the claim that it is effective? Here the pinch of salt must be even larger, I am afraid. I could not find a single trial that confirmed the notion. For backing up their claims, the manufacturers offer a few references, but if you look them up, you will find that they were not done with the mixture of ingredients contained in Brite.

So, what is the conclusion?

Based on the evidence that I have seen, the herbal drink ‘Brite’ has not been shown to be an effective nootropic. In addition, there are legitimate concerns about the safety of the product. I for one will therefore not purchase the (rather expensive) drink.

Yes, Today is ‘WORLD SLEEP DAY‘ and you are probably in bed hoping this post will put you back to sleep.

This study aimed to synthesise the best available evidence on the safety and efficacy of using moxibustion and/or acupuncture to manage cancer-related insomnia (CRI).

The PRISMA framework guided the review. Nine databases were searched from its inception to July 2020, published in English or Chinese. Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) of moxibustion and or acupuncture for the treatment of CRI were selected for inclusion. The methodological quality was assessed using the method suggested by the Cochrane collaboration. The Cochrane Review Manager was used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Fourteen RCTs met the eligibility criteria; 7 came from China. Twelve RCTs used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score as continuous data and a meta-analysis showed positive effects of moxibustion and or acupuncture (n = 997, mean difference (MD) = -1.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) = -2.75 to -0.94, p < 0.01). Five RCTs using continuous data and a meta-analysis in these studies also showed significant difference between two groups (n = 358, risk ratio (RR) = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.26-0.80, I 2 = 39%).

The authors concluded that the meta-analyses demonstrated that moxibustion and or acupuncture showed a positive effect in managing CRI. Such modalities could be considered an add-on option in the current CRI management regimen.

Even at the risk of endangering your sleep, I disagree with this conclusion. Here are some of my reasons:

- Chinese acupuncture trials invariably are positive which means they are as reliable as a 4£ note.

- Most trials were of poor methodological quality.

- Only one made an attempt to control for placebo effects.

- Many followed the A+B versus B design which invariably produces (false-) positive results.

- Only 4 out of 14 studies mentioned adverse events which means that 10 violated research ethics.

Sorry to have disturbed your sleep!

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is a chronic degenerative condition causing marked thickening and fibrosis of the plantar fascia, and collagen necrosis, chondroid metaplasia and calcification. There is little convincing evidence in support of various approaches, including homeopathy, for treating PF. This study was undertaken to examine the efficacy of individualized homeopathic medicines (IHMs) compared with placebo in the treatment of PF.

This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at the outpatient departments of Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital, West Bengal, India. Patients were randomized to receive either IHMs or identical-looking placebo in the mutual context of conservative non-medicinal management. The Foot Function Index (FFI) questionnaire, as an outcome measure, was administered at baseline, and every month, up to 3 months. Group differences (unpaired t-tests) and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated on an intention-to-treat sample. The sample was analyzed statistically after adjusting for baseline differences.

The target sample size was 128; however, only 75 could be enrolled (IHMs: 37; Placebo: 38). Attrition rate was 9.3% (IHMs: 4, Placebo: 3). Differences between groups in total FFI% score favored IHMs against placebo at all the time points, with large effect sizes: month 1 (mean difference, -10.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], -15.7 to -4.2; p = 0.001; d = 0.8); month 2 (mean difference, -14.3; 95% CI, -20.4 to -8.2; p <0.001; d = 1.1); and month 3 (mean difference, -23.3; 95% CI, -30.5 to -16.2; p <0.001; d = 1.5). Similar significant results were also observed on three FFI sub-scales (pain%, disability%, and activity limitation%). Natrum muriaticum (n = 14; 18.7%) and Rhus toxicodendron and Ruta graveolens (n = 11 each; 14.7%) were the most frequently prescribed medicines. No harms, serious adverse events, or intercurrent illnesses were recorded in either of the groups.

The authors concluded that IHMs acted significantly better than placebo in the treatment of PF; however, the trial being underpowered, the results should be interpreted as preliminary only. Independent replications are warranted.

It is nice to see homeopaths stress the importance of independent replication. It is less nice, however, to note their main conclusion:

IHMs acted significantly better than placebo.

This essentially is what will stick in the minds of the pro-homeopathy reader, and this is the information that will enter into future meta-analyses and systematic reviews of homeopathy. But this is also untrue! The qualifier that follows is but a lame excuse for drawing a wrong conclusion. In my view, a correct conclusion would read something like this:

Our study failed to recruit a sufficient number of patients. Therefore, no conclusions about the efficacy of IHM can be drawn from it.

Vaccine hesitancy is currently recognized by the WHO as a major threat to global health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a growing interest in the role of social media in the propagation of false information and fringe narratives regarding vaccination. Using a sample of approximately 60 billion tweets, Danish investigators conducted a large-scale analysis of the vaccine discourse on Twitter. They used methods from deep learning and transfer learning to estimate the vaccine sentiments expressed in tweets, then categorize individual-level user attitudes towards vaccines. Drawing on an interaction graph representing mutual interactions between users, They analyzed the interplay between vaccine stances, interaction network, and the information sources shared by users in vaccine-related contexts.

The results show that strongly anti-vaccine users frequently share content from sources of a commercial nature; typically sources that sell alternative health products for profit. An interesting aspect of this finding is that concerns regarding commercial conflicts of interests are often cited as one of the major factors in vaccine hesitancy.

The authors furthermore demonstrate that the debate is highly polarized, in the sense that users with similar stances on vaccination interact preferentially with one another. Extending this insight, the authors provide evidence of an epistemic echo chamber effect, where users are exposed to highly dissimilar sources of vaccine information, enforcing the vaccination stance of their contacts.

The authors concluded that their findings highlight the importance of understanding and addressing vaccine mis- and disinformation in the context in which they are disseminated in social networks.

In the article, the authors comment that their findings paint a picture of the vaccine discourse on Twitter as highly polarized, where users who express similar sentiments regarding vaccinations are more likely to interact with one another, and tend to share contents from similar sources. Focusing on users whose vaccination stances are the positive and negative extremes of the spectrum, we observe relatively disjoint ‘epistemic echo chambers’ which imply that members of the two groups of users rarely interact, and in which users experience highly dissimilar ‘information landscapes’ depending on their stance. Finally, we find that strongly anti-vaccine users much more frequently share information from actors with a vested commercial interest in promoting medical misinformation.

One implication of these findings is that online (medical) misinformation may present an even greater problem than previously thought, because beliefs and behaviors in tightly knit, internally homogeneous communities are more resilient, and provide fertile ground for fringe narratives, while mainstream information is attenuated. Furthermore, such polarization of communities may become self-perpetuating, because individuals avoid those not sharing their views, or because exposure to mainstream information might further entrench fringe viewpoints.

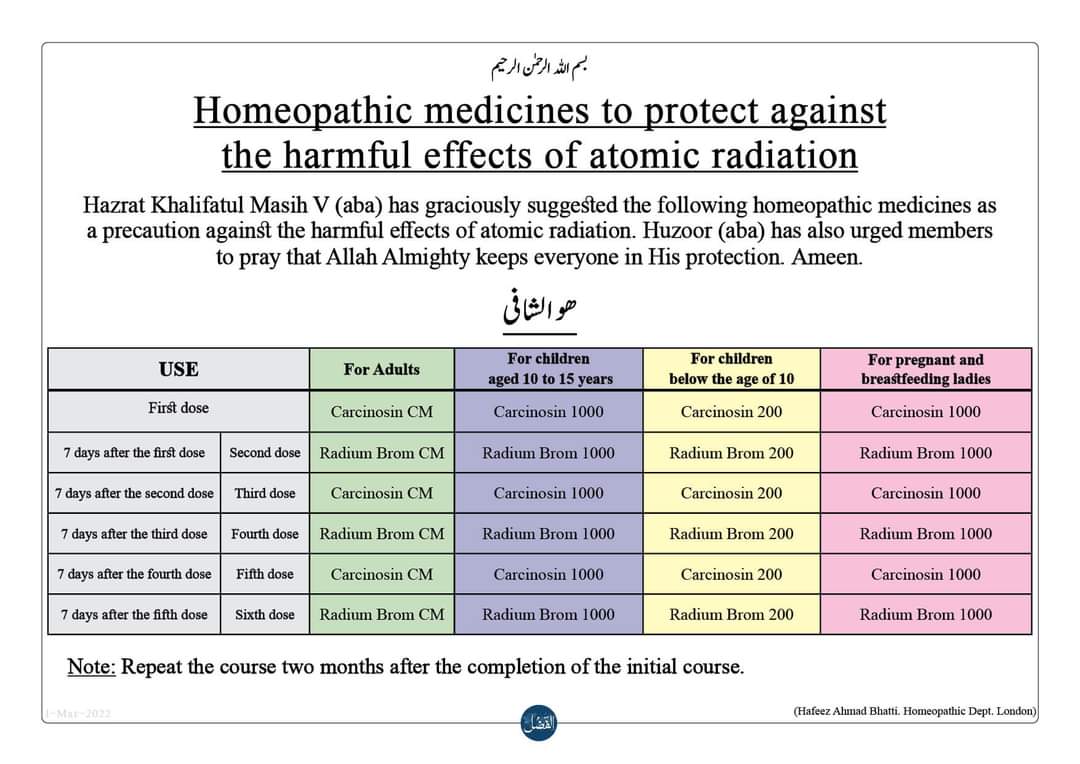

Yes, the fear of nuclear radiation has gripped the minds of many consumers. And who would blame them? We are all frightened of Putin’s next move. There is plenty of uncertainty. But, let me assure you, there is one certainty:

Homeopathy does not help against the effects of nuclear radiation.

But this indisputable fact has never stopped a homeopath.

Many of them are currently trying to persuade us that homeopathy can protect us. Here, for example, is something I found on Twitter:

But there is more, much more. If you go on the Internet, you find dozens of websites making wild claims. Here is just one example:

Homeopathic remedies as a preventive for adults

To be taken on an annual or bi-annual basis:

Week 1: Carcinosin in CM potency

Week 2: Radium Bromide in CM potency

Week 3: Carcinosin in CM potency

Week 4: Radium Bromide in CM potency

Week 5: Carcinosin in CM potency

Week 6: Radium Bromide in CM potency

Homeopathic remedies as a preventive for children (13 years old)

100

To be taken on an annual or bi-annual basis:

Week 1: Carcinosin in 1000 potency

Week 2: Radium Bromide in 1000 potency

Week 3: Carcinosin in 1000 potency

Week 4: Radium Bromide in 1000 potency

Week 5: Carcinosin in 1000 potency

Week 6: Radium Bromide in 1000 potency.

___________________________

Ridiculous? YES

Irresponsible? YES

Dangerous? YES

It’s high time to stop this nonsense!

The Nobel Prize laureate Luc Montagnier has died at the age of 89.

Montagnier became the hero of the realm of homeopathy when he published findings suggesting that ultra-molecular dilutions are not just pure water but might have some activity. In this context, he has been mentioned repeatedly on this blog. During the years that followed his support for homeopathy, things got from bad to worse, and Montagnier managed to alienate most of the scientific community.

Amongst other things, he became a champion of the anti-vax movement, supported the view that vaccination causes autism, and argued that viral infections including HIV could be cured by diet. During the pandemic, he then claimed that Sars-CoV-2 had originated from a laboratory experiment attempting to combine coronavirus and HIV. On French television, he claimed that vaccination was an “enormous mistake” that would only promote the spread of new variants.

Before Montagnier became a victim of ‘Nobelitis‘, he had a brilliant career as a virologist in his world-famous Paris lab. A co-worker of Montagnier, Barré-Sinoussi, managed to isolate a retrovirus from an AIDS patient in 1983. They called it ‘lymphadenopathy-associated virus’, and concluded that it may be involved in several pathological syndromes, including AIDS.

Meanwhile, in the US, Gallo had identified a family of immunodeficiency retroviruses that he called human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV). In 1984, Gallo announced that one of these viruses was the cause of AIDS. The US government swiftly patented a blood test for detecting antibodies to it. Thus it became possible to screen for the virus in the blood.

When it became clear that material used in Gallo’s studies included samples that Montagnier had supplied in 1983, one of the fiercest rows in the history of science ensued. Eventually, negotiations between the two governments settled it by resolving that the two scientists should be equally credited. In 2002, Gallo and Montagnier published a joint paper acknowledging each other’s role: Montagnier’s team discovered HIV, and Gallo’s proved it caused AIDS. When Gallo was excluded from the Nobel prize given in 2008 to Montagnier and Barré-Sinoussi, the world of science was stunned. The spectacular dispute between Galo and Montagnier became the subject of a movie and several books.

Montagnier died on 8/2/2022 leaving behind his wife Dorothea and their three children, Anne-Marie, Francine, and Jean-Luc.

The new issue of the BMJ carries an article on acupuncture that cries out for a response. Here, I show you the original article followed by my short comments. For clarity, I have omitted the references from the article and added references that refer to my comments.

_________________________________________

Conventional allopathic medicine [1]—medications and surgery [2] used in conventional systems of medicine to treat or prevent disease [3]—is often expensive, can cause side effects and harm, and is not always the optimal treatment for long term conditions such as chronic pain [4]. Where conventional treatments have not been successful, acupuncture and other traditional and complementary medicines have potential to play a role in optimal patient care [5].

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2019 global report, acupuncture is widely used across the world. [6] In some countries acupuncture is covered by health insurance and established regulations. [7] In the US, practitioners administer over 10 million acupuncture treatments annually. [6] In the UK, clinicians administer over 4 million acupuncture treatments annually, and it is provided on the NHS. [6]

Given the widespread use of acupuncture as a complementary therapy alongside conventional medicine, there has been an increase in global research interest and funding support over recent decades. In 2009, the European Commission launched a Good Practice in Traditional Chinese Medicine Research (GP-TCM) funding initiative in 19 countries. [7] The GP-TCM grant aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of acupuncture as well as other traditional Chinese medicine interventions.

In China, acupuncture is an important focus of the national research agenda and receives substantial research funding. [8] In 2016, the state council published a national strategy supporting universal access to acupuncture by 2020. China has established more than 79 evidence-based traditional Chinese medicine or integrative medicine research centers. [9]

Given the broad clinical application and rapid increase in funding support for acupuncture research, researchers now have additional opportunities to produce high-quality studies. However, for this to be successful, acupuncture research must address both methodological limitations and unique research challenges.

This new collection of articles, published in The BMJ, analyses the progress of developing high quality research studies on acupuncture, summarises the current status, and provides critical methodological guidance regarding the production of clinical evidence on randomised controlled trials, clinical practice guidelines and health economic evidence. It also assesses the number and quality of systematic reviews of acupuncture. [10] We hope that the collection will help inform the development of clinical practice guidelines, health policy, and reimbursement decisions. [11]

The articles document the progress of acupuncture research. In our view, the emerging evidence base on the use of acupuncture warrants further integration and application of acupuncture into conventional medicine. [12] National, regional, and international organisations and health systems should facilitate this process and support further rigorous acupuncture research.

Footnotes

This article is part of a collection funded by the special purpose funds for the belt and road, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Innovation Team and Talents Cultivation Program of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Special Project of “Lingnan Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine” of the 2019 Guangdong Key Research and Development Program, and the Project of First Class Universities and High-level Dual Discipline for Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. The BMJ commissioned, peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish. Kamran Abbasi was the lead editor for The BMJ. Yu-Qing Zhang advised on commissioning for the collection, designed the topic of the series, and coordinated the author teams. Gordon Guyatt provided valuable advice and guidance. [13]

1. Allopathic medicine is the term Samuel Hahnemann coined for defaming conventional medicine. Using it in the first sentence of the article sets the scene very well.

2. Medicine is much more than ‘medications and surgery’. To imply otherwise is a strawman fallacy.

3. What about rehabilitation medicine?

4. ‘Conventional medicine is not always the optimal treatment’? This statement is very confusing and wrong. It is true that conventional medicine is not always effective. However, it is by definition the best we currently have and therefore it IS optimal.

5. Another fallacy: non sequitur

6. Another fallacy: appeal to popularity.

7. Yet another fallacy: appeal to authority.

8. TCM is heavily promoted by China not least because it is a most lucrative source of income.

9. Several research groups have shown that 100% of acupuncture research coming out of China report positive results. This casts serious doubt on the reliability of these studies (see, for instance, here, here, and here).

10. It has been noted that more than 80 percent of clinical data from China is fabricated.

11. Based on the points raised above, it seems to me that the collection’s aim is not to provide objective information but uncritical promotion.

12. I find it telling that the authors do not even consider the possibility that rigorous research might demonstrate that acupuncture cannot generate more good than harm.

13. This statement essentially admits that the series of articles constitutes paid advertising for TCM. The BMJ’s peer-review process must have been less than rigorous in this case.