acupuncture

Power Point therapy (PPT) is not what you might think it is; it is not related to a presentation using power point. Power According to the authors of the so far only study of PPT, it is based on the theories of classic acupuncture, neuromuscular reflexology, and systems theoretical approaches like biocybernetics. It has been developed after four decades of experience by Mr. Gerhard Egger, an Austrian therapist. Hundreds of massage and physiotherapists in Europe were trained to use it, and apply it currently in their practice. The treatment can be easily learned. It is taught by professional PPT therapists to students and patients for self-application in weekend courses, followed by advanced courses for specialists.

The core hypothesis of the PPT system is that various pain syndromes have its origin, among others, in a functional pelvic obliquity. This in turn leads to a static imbalance in the posture of the body. This may result in mechanical strain and possible spinal nerve irritation that may radiate and thus affect dermatomes, myotomes, enterotomes, sclerotomes, and neurotomes of one or more vertebra segments. Therefore, treating reflex zones for the pelvis would reduce and possibly resolve the functional obliquity, improve the statics, and thus cure the pain through improved function. In addition, reflex therapy might be beneficial also in patients with unknown causes of back pain. PPT uses blunt needle tips to apply pressure to specific reflex points on the nose, hand, and feet. PPT has been used for more than 10 years in treating patients with musculoskeletal problems, especially lower back pain.

Sounds more than a little weird?

Yes, I agree.

Perhaps we need some real evidence.

The aim of this RCT was to compare 10 units of PPT of 10 min each, with 10 units of standard physiotherapy of 30 min each. Outcomes were functional scores (Roland Morris Disability, Oswestry, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Linton-Halldén – primary outcome) and health-related quality of life (SF-36), as well as blinded assessments by clinicians (secondary outcome).

Eighty patients consented and were randomized, 41 to PPT, 39 to physiotherapy. Measurements were taken at baseline, after the first and after the last treatment (approximately 5 weeks after enrolment). Multivariate linear models of covariance showed significant effects of time and group and for the quality of life variables also a significant interaction of time by group. Clinician-documented variables showed significant differences at follow-up.

The authors concluded that both physiotherapy and PPT improve subacute low back pain significantly. PPT is likely more effective and should be studied further.

I was tempted to say ‘there is nothing fundamentally wrong with this study’. But then I hesitated and, on second thought, found a few things that do concern me:

- The theory on which PPT is based is not plausible (to put it mildly).

- It would have been easy to conduct a placebo-controlled trial of PPT. The authors justify their odd study design stating this: This was the very first randomized controlled trial of PPT. Therefore, the study has to be considered a pilot. For a pivotal study, a clearly defined primary outcome would have been essential. This was not possible, as no previous experience was able to suggest which outcome would be the best. In my view, this is utter nonsense. Defining the primary outcome of a back pain study is not rocket science; there are plenty of validated measures of pain.

- The study was funded by the Foundation of Natural Sciences and Technical Research in Vaduz, Liechtenstein. I cannot find such an organisation on the Internet.

- The senior author of this study is Prof H Walach who won the prestigious award for pseudoscientist of the year 2012.

- Walach provides no less than three affiliations, including the ‘Change Health Science Institute, Berlin, Germany’. I cannot find such an organisation on the Internet.

- The trial was published in a less than prestigious SCAM journal, ‘Forschende Komplementarmedizin‘ – its editor in-chief: Harald Walach.

So, in view of these concerns, I think PPT might not be nearly as promising as this study implies. Personally, I will wait for an independent replication of Walach’s findings.

So-called alternative medicine (SCAM) for animals is popular. A recent survey suggested that 76% of US dog and cat owners use some form of SCAM. Another survey showed that about one quarter of all US veterinary medical schools run educational programs in SCAM. Amazon currently offers more that 4000 books on the subject.

The range of SCAMs advocated for use in animals is huge and similar to that promoted for use in humans; the most commonly employed practices seem to include acupuncture, chiropractic, energy healing, homeopathy (as discussed in the previous post) and dietary supplements. In this article, I will briefly discuss the remaining 4 categories.

ACUPUNCTURE

Acupuncture is the insertion of needles at acupuncture points on the skin for therapeutic purposes. Many acupuncturists claim that, because it is over 2 000 years old, acupuncture has ‘stood the test of time’ and its long history proves acupuncture’s efficacy and safety. However, a long history of usage proves very little and might even just demonstrate that acupuncture is based on the pre-scientific myths that dominated our ancient past.

There are many different forms of acupuncture. Acupuncture points can allegedly be stimulated not just by inserting needles (the most common way) but also with heat, electrical currents, ultrasound, pressure, bee-stings, injections, light, colour, etc. Then there is body acupuncture, ear acupuncture and even tongue acupuncture. Traditional Chinese acupuncture is based on the Taoist philosophy of the balance between two life-forces, ‘yin and yang’. In contrast, medical acupuncturists tend to cite neurophysiological theories as to how acupuncture might work; even though some of these may appear plausible, they nevertheless are mere theories and constitute no proof for acupuncture’s validity.

The therapeutic claims made for acupuncture are legion. According to the traditional view, acupuncture is useful for virtually every condition. According to ‘Western’ acupuncturists, acupuncture is effective mostly for chronic pain. Acupuncture has, for instance, been used to improve mobility in dogs with musculoskeletal pain, to relieve pain associated with cervical neurological disease in dogs, for respiratory resuscitation of new-born kittens, and for treatment of certain immune-mediated disorders in small animals.

While the use of acupuncture seems to gain popularity, the evidence fails to support this. Our systematic review of acupuncture (to the best of my knowledge the only one on the subject) in animals included 14 randomized controlled trials and 17 non-randomized controlled studies. The methodologic quality of these trials was variable but, on average, it was low. For cutaneous pain and diarrhoea, encouraging evidence emerged that might warrant further investigation. Single studies reported some positive inter-group differences for spinal cord injury, Cushing’s syndrome, lung function, hepatitis, and rumen acidosis. However, these trials require independent replication. We concluded that, overall, there is no compelling evidence to recommend or reject acupuncture for any condition in domestic animals. Some encouraging data do exist that warrant further investigation in independent rigorous trials.

Serious complications of acupuncture are on record and have repeatedly been discussed on this blog: acupuncture needles can, for instance, injure vital organs like the lungs or the heart, and they can introduce infections into the body, e. g. hepatitis. About 100 human fatalities after acupuncture have been reported in the medical literature – a figure which, due to lack of a monitoring system, may disclose just the tip of an iceberg. Information on adverse effects of acupuncture in animals is currently not available.

Given that there is no good evidence that acupuncture works in animals, the risk/benefit balance of acupuncture cannot be positive.

CHIROPRACTIC

Chiropractic was created by D D Palmer (1845-1913), an American magnetic healer who, in 1895, manipulated the neck of a deaf janitor, allegedly curing his deafness. Chiropractic was initially promoted as a cure-all by Palmer who claimed that 95% of diseases were due to subluxations of spinal joints. Subluxations became the cornerstone of chiropractic ‘philosophy’, and chiropractors who adhere to Palmer’s gospel diagnose subluxation in nearly 100% of the population – even in individuals who are completely disease and symptom-free. Yet subluxations, as understood by chiropractors, do not exist.

There is no good evidence that chiropractic spinal manipulation might be effective for animals. A review of the evidence for different forms of manual therapies for managing acute or chronic pain syndromes in horses concluded that further research is needed to assess the efficacy of specific manual therapy techniques and their contribution to multimodal protocols for managing specific somatic pain conditions in horses. For other animal species or other health conditions, the evidence is even less convincing.

In humans, spinal manipulation is associated with serious complications (regularly discussed in previous posts), usually caused by neck manipulation damaging the vertebral artery resulting in a stroke and even death. Several hundred such cases have been documented in the medical literature – but, as there is no system in place to monitor such events, the true figure is almost certainly much larger. To the best of my knowledge, similar events have not been reported in animals.

Since there is no good evidence that chiropractic spinal manipulations work in animals, the risk/benefit balance of chiropractic fails to be positive.

ENERGY HEALING

Energy healing is an umbrella term for a range of paranormal healing practices, e. g. Reiki, Therapeutic Touch, Johrei healing, faith healing. Their common denominator is the belief in an ‘energy’ that can be used for therapeutic purposes. Forms of energy healing have existed in many ancient cultures. The ‘New Age’ movement has brought about a revival of these ideas, and today ‘energy’ healing systems are amongst the most popular alternative therapies in many countries.

Energy healing relies on the esoteric belief in some form of ‘energy’ which refers to some life force such as chi in Traditional Chinese Medicine, or prana in Ayurvedic medicine. Some proponents employ terminology from quantum physics and other ‘cutting-edge’ science to give their treatments a scientific flair which, upon closer scrutiny, turns out to be little more than a veneer of pseudo-science.

Considering its implausibility, energy healing has attracted a surprisingly high level of research activity in the form of clinical trials on human patients. Generally speaking, the methodologically best trials of energy healing fail to demonstrate that it generates effects beyond placebo. There are few studies of energy healing in animals, and those that are available are frequently less than rigorous (see for instance here and here). Overall, there is no good evidence to suggest that ‘energy’ healing is effective in animals.

Even though energy healing is per se harmless, it can do untold damage, not least because it can lead to neglect of effective treatments and it undermines rationality in our societies. Its risk/benefit balance therefore fails to be positive.

DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS

Dietary supplements for veterinary use form a category of remedies that, in most countries, is a regulatory grey area. Supplements can contain all sorts of ingredients, from minerals and vitamins to plants and synthetic substances. Therefore, generalisations across all types of supplements are impossible. The therapeutic claims that are being made for supplements are numerous and often unsubstantiated. Although they are usually promoted as natural and safe, dietary supplements do not have necessarily either of these qualities. For example, in the following situations, supplements can be harmful:

- Combining one supplement with another supplement or with prescribed medicines

- Substituting supplements for prescription medicines

- Overdosing some supplements, such as vitamin A, vitamin D, or iron

Examples of currently most popular supplements for use in animals include chondroitin, glucosamine, probiotics, vitamins, minerals, lutein, L-carnitine, taurine, amino acids, enzymes, St John’s wort, evening primrose oil, garlic and many other herbal remedies. For many supplements taken orally, the bioavailability might be low. There is a paucity of studies testing the efficacy of dietary supplements in animals. Three recent exceptions (all of which require independent replication) are:

- A trial showing that the dietary supplementation with Maca increased sperm production in stallions.

- A study demonstrating that curcumin supplementation appeared to reduce arthritis pain in dogs.

- An investigation suggesting that royal jelly supplementation can improve the egg quality of hens.

Dietary supplements are promoted as being free of direct risks. On closer inspection, this notion turns out to be little more than an advertising slogan. As discussed repeatedly on this blog, some supplements contain toxic materials, contaminants or adulterants and thus have the potential to do harm. A report rightly concluded that many challenges stand in the way of determining whether or not animal dietary supplements are safe and at what dosage. Supplements considered safe in humans and other cross-species are not always safe in horses, dogs, and cats. An adverse event reporting system is badly needed. And finally, regulations dealing with animal dietary supplements are in disarray. Clear and precise regulations are needed to allow only safe dietary supplements on the market.

It is impossible to generalise about the risk/benefit balance of dietary supplements; however, caution is advisable.

CONCLUSION

SCAM for animals is an important subject, not least because of the current popularity of many treatments that fall under this umbrella. For most therapies, the evidence is woefully incomplete. This means that most SCAMs are unproven. Arguably, it is unethical to use unproven medicines in routine veterinary care.

PS

I was invited several months ago to write this article for VETERINARY RECORD. It was submitted to peer review and subsequently I withdrew my submission. The above post is a slightly revised version of the original (in which I used the term ‘alternative medicine’ rather than ‘SCAM’) which also included a section on homeopathy (see my previous post). The reason for the decision to withdraw this article was the following comment by the managing editor of VETERINARY RECORD: A good number of vets use these therapies and a more balanced view that still sets out their efficacy (or otherwise) would be more useful for the readership.

Acupuncture is all over the news today. The reason is a study just out in BMJ-Open.

The aim of this new RCT was to investigate the efficacy of a standardised brief acupuncture approach for women with moderate-tosevere menopausal symptoms. Nine Danish primary care practices recruited 70 women with moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms. Nine general practitioners with accredited education in acupuncture administered the treatments.

The acupuncture style was western medical with a standardised approach in the pre-defined acupuncture points CV-3, CV-4, LR-8, SP-6 and SP-9. The intervention group received one treatment for five consecutive weeks. The control group received no acupuncture but was offered treatment after 6 weeks. Outcomes were the differences between the two groups in changes to mean scores using the scales in the MenoScores Questionnaire, measured from baseline to week 6. The primary outcome was the hot flushes scale; the secondary outcomes were the other scales in the questionnaire. All analyses were based on intention-to-treat analysis.

Thirty-six patients received the intervention, and 34 were in the control group. Four participants dropped out before week 6. The acupuncture intervention significantly decreased hot flushes, day-and-night sweats, general sweating, menopausal-specific sleeping problems, emotional symptoms, physical symptoms and skin and hair symptoms compared with the control group at the 6-week follow-up. The pattern of decrease in hot flushes, emotional symptoms, skin and hair symptoms was already apparent three weeks into the study. Mild potential adverse effects were reported by four participants, but no severe adverse effects were reported.

The authors concluded that the standardised and brief acupuncture treatment produced a fast and clinically relevant reduction in moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms during the six-week intervention.

The only thing that I find amazing here is the fact the a reputable journal published such a flawed trial arriving at such misleading conclusions.

- The authors call it a ‘pragmatic’ trial. Yet it excluded far too many patients to realistically qualify for this characterisation.

- The trial had no adequate control group, i.e. one that can account for placebo effects. Thus the observed outcomes are entirely in keeping with the powerful placebo effect that acupuncture undeniably has.

- The authors nevertheless conclude that ‘acupuncture treatment produced a fast and clinically relevant reduction’ of symptoms.

- They also state that they used this design because no validated sham acupuncture method exists. This is demonstrably wrong.

- In my view, such misleading statements might even amount to scientific misconduct.

So, what would be the result of a trial that is rigorous and does adequately control for placebo-effects? Luckily, we do not need to rely on speculation here; we have a study to demonstrate the result:

Background: Hot flashes (HFs) affect up to 75% of menopausal women and pose a considerable health and financial burden. Evidence of acupuncture efficacy as an HF treatment is conflicting.

Objective: To assess the efficacy of Chinese medicine acupuncture against sham acupuncture for menopausal HFs.

Design: Stratified, blind (participants, outcome assessors, and investigators, but not treating acupuncturists), parallel, randomized, sham-controlled trial with equal allocation. (Australia New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12611000393954)

Setting: Community in Australia.

Participants: Women older than 40 years in the late menopausal transition or postmenopause with at least 7 moderate HFs daily, meeting criteria for Chinese medicine diagnosis of kidney yin deficiency.

Interventions:10 treatments over 8 weeks of either standardized Chinese medicine needle acupuncture designed to treat kidney yin deficiency or noninsertive sham acupuncture.

Measurements: The primary outcome was HF score at the end of treatment. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, anxiety, depression, and adverse events. Participants were assessed at 4 weeks, the end of treatment, and then 3 and 6 months after the end of treatment. Intention-to-treat analysis was conducted with linear mixed-effects models.

Results: 327 women were randomly assigned to acupuncture (n = 163) or sham acupuncture (n = 164). At the end of treatment, 16% of participants in the acupuncture group and 13% in the sham group were lost to follow-up. Mean HF scores at the end of treatment were 15.36 in the acupuncture group and 15.04 in the sham group (mean difference, 0.33 [95% CI, −1.87 to 2.52]; P = 0.77). No serious adverse events were reported.

Limitation: Participants were predominantly Caucasian and did not have breast cancer or surgical menopause.

Conclusion: Chinese medicine acupuncture was not superior to noninsertive sham acupuncture for women with moderately severe menopausal HFs.

My conclusion from all this is simple: acupuncture trials generate positive findings, provided the researchers fail to test it rigorously.

An article referring to comments Prof David Colquhoun and I recently made in THE TIMES about acupuncture for children caught my attention. In it, Rebecca Avern, an acupuncturist specialising in paediatrics and heading the clinical programme at the College of Integrated Chinese Medicine, makes a several statements which deserve a comment. Here is her article in full, followed by my short comments.

START OF QUOTE

However, it included some negative quotes from our old friends Ernst and Colquhoun. The first was Ernst stating that he was ‘not aware of any sound evidence showing that acupuncture is effective for any childhood conditions’. Colquhoun went further to state that there simply is not ‘the slightest bit of evidence to suggest that acupuncture helps anything in children’. Whilst they may not be aware of it, good evidence does exist, albeit for a limited number of conditions. For example, a 2016 meta-analysis and systematic review of the use of acupuncture for post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) concluded that children who received acupuncture had a significantly lower risk of PONV than those in the control group or those who received conventional drug therapy.[i]

Ernst went on to mention the hypothetical risk of puncturing a child’s internal organs but he failed to provide evidence of any actual harm. A 2011 systematic review analysing decades of acupuncture in children aged 0 to 17 years prompted investigators to conclude that acupuncture can be characterised as ‘safe’ for children.[ii]

Ernst also mentioned what he perceived is a far greater risk. He expressed concern that children would miss out on ‘effective’ treatment because they are having acupuncture. In my experience running a paediatric acupuncture clinic in Oxford, this is not the case. Children almost invariably come already having received a diagnosis from either their GP or a paediatric specialist. They are seeking treatment, such as in the case of bedwetting or chronic fatigue syndrome, because orthodox medicine is unable to effectively treat or even manage their condition. Alternatively, their condition is being managed by medication which may be causing side effects.

When it comes to their children, even those parents who may have reservations about orthodox medicine, tend to ensure their child has received all the appropriate exploratory tests. I have yet to meet a parent who will not ensure that their child, who has a serious condition, has the necessary medication, which in some cases may save their lives, such as salbutamol (usually marketed as Ventolin) for asthma or an EpiPen for anaphylactic reactions. If a child comes to the clinic where this turns out not to be the case, thankfully all BAcC members have training in a level of conventional medical sciences which enables them to spot ‘red flags’. This means that they will inform the parent that their child needs orthodox treatment either instead of or alongside acupuncture.

The article ended with a final comment from Colquhoun who believes that ‘sticking pins in babies is a rather unpleasant form of health fraud’. It is hard not to take exception to the phrase ‘sticking pins in’, whereas what we actually do is gently and precisely insert fine, sterile acupuncture needles. The needles used to treat babies and children are usually approximately 0.16mm in breadth. The average number of needles used per treatment is between two and six, and the needles are not retained. A ‘treatment’ may include not only needling, but also diet and lifestyle advice, massage, moxa, and parental education. Most babies and children find an acupuncture treatment perfectly acceptable, as the video below illustrates.

The views of Colquhoun and Ernst also beg the question of how acupuncture compares in terms of safety and proven efficacy with orthodox medical treatments given to children. Many medications given to children are so called ‘off-label’ because it is challenging to get ethical approval for randomised controlled trials in children. This means that children are prescribed medicines that are not authorised in terms of age, weight, indications, or routes of administration. A 2015 study noted that prescribers and caregivers ‘must be aware of the risk of potential serious ADRs (adverse drug reactions)’ when prescribing off-label medicines to children.[iii]

There are several reasons for the rise in paediatric acupuncture to which the article referred. Most of the time, children get better when they have acupuncture. Secondly, parents see that the treatment is gentle and well tolerated by their children. Unburdened by chronic illness, a child can enjoy a carefree childhood, and they can regain a sense of themselves as healthy. A weight is lifted off the entire family when a child returns to health. It is my belief that parents, and children, vote with their feet and that, despite people such as Ernst and Colquhoun wishing it were otherwise, more and more children will receive the benefits of acupuncture.

[i] Shin HC et al, The effect of acupuncture on post-operative nausea and vomiting after pediatric tonsillectomy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Accessed January 2019 from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26864736

[ii] Franklin R, Few Serious Adverse Events in Pediatric Needle Acupuncture. Accessed January 2019from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/753934?src=trendmd_pilot

[iii] Aagaard L (2015) Off-Label and Unlicensed Prescribing of Medicines in Paediatric Populations: Occurrence and Safety Aspects. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. Accessed January 2019 from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/bcpt.12445

END OF QUOTE

- GOOD EVIDENCE: The systematic review cited by Mrs Avern was based mostly on poor-quality trials. It even included cohort studies without a control group. To name it as an example of good evidence, merely discloses an ignorance about what good evidence means.

- SAFETY: The article Mrs Avern referred to is a systematic review of reports on adverse events (AEs) of acupuncture in children. A total of 279 AEs were found. Of these, 25 were serious (12 cases of thumb deformity, 5 infections, and 1 case each of cardiac rupture, pneumothorax, nerve impairment, subarachnoid haemorrhage, intestinal obstruction, haemoptysis, reversible coma, and overnight hospitalization), 1 was moderate (infection), and 253 were mild. The mild AEs included pain, bruising, bleeding, and worsening of symptoms. Considering that there is no reporting system of such AEs, this list of AEs is, I think, concerning and justifies my concerns over the safety of acupuncture in children. The risks are certainly not ‘hypothetical’, as Mrs Avern claimed, and to call it thus seems to be in conflict with the highest standard of professional care (see below). Because the acupuncture community has still not established an effective AE-surveillance system, nobody can tell whether such events are frequent or rare. We all hope they are infrequent, but hope is a poor substitute for evidence.

- COMPARISON TO OTHER TREATMENTS: Mrs Avern seems to think that acupuncture has a better risk/benefit profile than conventional medicine. Having failed to show that acupuncture is effective and having demonstrated that it causes severe adverse effects, this assumption seems nothing but wishful thinking on her part.

- EXPERIENCE: Mrs Avern finishes her article by telling us that ‘children get better when they have acupuncture’. She seems to be oblivious to the fact that sick children usually get better no matter what. Perhaps the kids she treats would have improved even faster without her needles?

In conclusion, I do not doubt the good intentions of Mrs Avern for one minute; I just wished she were able to develop a minimum of critical thinking capacity. More importantly, I am concerned about the BRITISH ACUPUNCTURE COUNCIL, the organisation that published Mrs Avern’s article. On their website, they state: The British Acupuncture Council is committed to ensuring all patients receive the highest standard of professional care during their acupuncture treatment. Our Code of Professional Conduct governs ethical and professional behaviour, while the Code of Safe Practice sets benchmark standards for best practice in acupuncture. All BAcC members are bound by these codes. Who are they trying to fool?, I ask myself.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have a higher risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). Despite good evidence for effectiveness, acupuncture is often advocated for RA, and it has not been reported to prevent CHD in patients with RA.

The authors of this analysis aimed to assess the risk of developing CHD in acupuncture-users and non-users of patients with RA. They identified 29,741 patients with newly diagnosed RA from January 1997 to December 2010 from the Registry of Catastrophic Illness Patients Database from the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database. Among them, 10,199 patients received acupuncture (acupuncture users), and 19,542 patients did not receive acupuncture (no-acupuncture users). After performing 1:1 propensity score matching by sex, age, baseline comorbidity, conventional treatment, initial diagnostic year, and index year, there were 9932 patients in both the acupuncture and no-acupuncture cohorts. The main outcome was the diagnosis of CHD in patients with RA in the acupuncture and no-acupuncture cohorts.

Acupuncture users had a lower incidence of CHD than non-users (adjusted HR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.55-0.65). The estimated cumulative incidence of CHD was significantly lower in the acupuncture cohort (log-rank test, p < .001). Subgroup analysis showed that patients receiving manual acupuncture of traditional Chinese medicine style, electroacupuncture, or combination of both all had a lower incidence of CHD than patients never receiving acupuncture treatment. The beneficial effect of acupuncture on preventing CHD was independent of age, sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and statins use.

The authors concluded that this is the first large-scale study to reveal that acupuncture might have beneficial effect on reducing the risk of CHD in patients with RA. This study may provide useful information for clinical utilization and future studies.

Pigs might fly, but – call me a sceptic – I somehow doubt it almost as much as I doubt that acupuncture might have beneficial effect on reducing the risk of CHD.

Why?

Because of two reasons mainly:

- For the life of me, I cannot see a mechanism by which acupuncture achieves this extraordinary feast (the authors allege an anti-inflammatory effect of acupuncture which I find wholly unconvincing).

- There is a much simpler explanation for the observed outcomes.

The propensity score used here did, of course, only match the groups for a hand-full of factors. Yet there are many more that could play a part which the authors could not consider because they did not have the data to do so. The one that foremost comes to my mind is a generally healthier life-style of the patients using acupuncture. I think it stands to reason that people who bother to have and pay for an additional treatment are higher motivated to adhere to a life-style (e. g. smoking-cessation, exercise, nutrition, stress) that reduces the CHD-risk. And the influence of this factor could be very significant indeed. As the devil’s advocate, I could therefore even postulate that acupuncture itself had a slightly detrimental effect which, however, was over-ridden by the massive effect of the healthier life-style.

And the lesson to learn from all this?

Before we conclude about ‘beneficial effects’ of acupuncture or any other therapy, we need RCTs that effectively eliminate these rather obvious confounders.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is caused by the tendons in the wrist getting too tight and thus putting pressure on the nerves that run beneath them. The symptoms can include:

- pain in fingers, hand or arm,

- numb hands,

- tingling or ‘pins and needles’,

- a weak thumb or difficulty gripping.

These symptoms often start slowly and they can come and go but often get worse over time. They are usually worse at night and may keep patients from having a good night’s sleep.

The treatments advocated for CTS include painkillers, splints and just about every alternative therapy one can think of, particularly acupuncture. Acupuncture may be popular, but does it work?

This new Cochrane review was aimed at assessing the evidence for acupuncture and similar treatments for CTS. It included 12 studies with 869 participants. Ten studies reported the primary outcome of overall clinical improvement at short‐term follow‐up (3 months or less) after randomisation. Most studies could not be combined in a meta‐analysis due to heterogeneity, and all had an unclear or high overall risk of bias. Only 7 studies provided information on adverse events.

The authors (two of them are from my former Exeter team) found that, in comparison with placebo or sham-treatments, acupuncture and laser acupuncture have little or no effect in the short term on symptoms of CTS. It is uncertain whether acupuncture and related interventions are more or less effective in relieving symptoms of CTS than corticosteroid nerve blocks, oral corticosteroids, vitamin B12, ibuprofen, splints, or when added to NSAIDs plus vitamins, as the certainty of any conclusions from the evidence is low or very low and most evidence is short term. The included studies covered diverse interventions, had diverse designs, limited ethnic diversity, and clinical heterogeneity.

The authors concluded that high‐quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are necessary to rigorously assess the effects of acupuncture and related interventions upon symptoms of CTS. Based on moderate to very‐low certainty evidence, acupuncture was associated with no serious adverse events, or reported discomfort, pain, local paraesthesia and temporary skin bruises, but not all studies provided adverse event data.

This last point is one that I made very often: most trials of acupuncture fail to report adverse effects. This is doubtlessly unethical (it gives a false-positive overall impression about acupuncture’s safety). And what can you do with studies that are unethical? My answer is simple: bin them!

Most of the trials were of poor or very poor quality. Such studies tend to generate false-positive results. And what can you do with studies that are flimsy and misleading? My answer is simple: bin them!

So, what can we do with acupuncture trials of CTS? … I let you decide.

But binning the evidence offers little help to patients who suffer from chronic, progressive CTS. What can those patients do? Go and see a surgeon! (S)he will cure you with a relatively simply and safe operation; in all likelihood, you will never look back at dubious treatments.

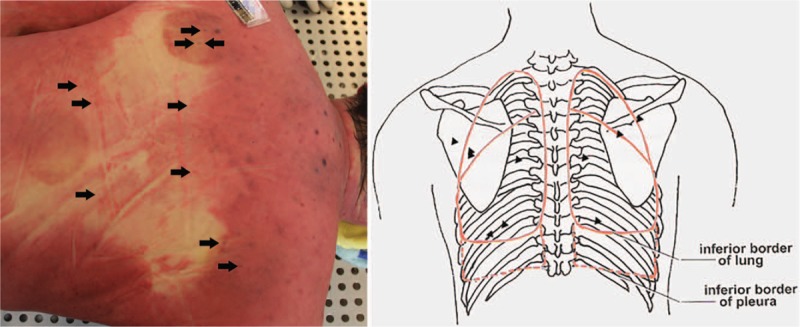

The most frequent of all potentially serious adverse events of acupuncture is pneumothorax. It happens when an acupuncture needle penetrates the lungs which subsequently deflate. The pulmonary collapse can be partial or complete as well as one or two sided. This new case-report shows just how serious a pneumothorax can be.

A 52-year-old man underwent acupuncture and cupping treatment at an illegal Chinese medicine clinic for neck and back discomfort. Multiple 0.25 mm × 75 mm needles were utilized and the acupuncture points were located in the middle and on both sides of the upper back and the middle of the lower back. He was admitted to hospital with severe dyspnoea about 30 hours later. On admission, the patient was lucid, was gasping, had apnoea and low respiratory murmur, accompanied by some wheeze in both sides of the lungs. Because of the respiratory difficulty, the patient could hardly speak. After primary physical examination, he was suspected of having a foreign body airway obstruction. Around 30 minutes after admission, the patient suddenly became unconscious and died despite attempts of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Whole-body post-mortem computed tomography of the victim revealed the collapse of the both lungs and mediastinal compression, which were also confirmed by autopsy. More than 20 pinprick injuries were found on the skin of the upper and lower back in which multiple pinpricks were located on the body surface projection of the lungs. The cause of death was determined as acute respiratory and circulatory failure due to acupuncture-induced bilateral tension pneumothorax.

The authors caution that acupuncture-induced tension pneumothorax is rare and should be recognized by forensic pathologists. Postmortem computed tomography can be used to detect and accurately evaluate the severity of pneumothorax before autopsy and can play a supporting role in determining the cause of death.

The authors mention that pneumothorax is the most frequent but by no means the only serious complication of acupuncture. Other adverse events include:

- central nervous system injury,

- infection,

- epidural haematoma,

- subarachnoid haemorrhage,

- cardiac tamponade,

- gallbladder perforation,

- hepatitis.

No other possible lung diseases that may lead to bilateral spontaneous pneumothorax were found. The needles used in the case left tiny perforations in the victim’s lungs. A small amount of air continued to slowly enter the chest cavities over a long period. The victim possibly tolerated the mild discomfort and did not pay attention when early symptoms appeared. It took 30 hours to develop into symptoms of a severe pneumothorax, and then the victim was sent to the hospital. There he was misdiagnosed, not adequately treated and thus died. I applaud the authors for nevertheless publishing this case-report.

This case occurred in China. Acupuncturists might argue that such things would not happen in Western countries where acupuncturists are fully trained and aware of the danger. They would be mistaken – and alarmingly, there is no surveillance system that could tell us how often serious complications occur.

This systematic review was aimed at evaluating the effects of acupuncture on the quality of life of migraineurs. Only randomized controlled trials that were published in Chinese and English were included. In total, 62 trials were included for the final analysis; 50 trials were from China, 3 from Brazil, 3 from Germany, 2 from Italy and the rest came from Iran, Israel, Australia and Sweden.

Acupuncture resulted in lower Visual Analog Scale scores than medication at 1 month after treatment and 1-3 months after treatment. Compared with sham acupuncture, acupuncture resulted in lower Visual Analog Scale scores at 1 month after treatment.

The authors concluded that acupuncture exhibits certain efficacy both in the treatment and prevention of migraines, which is superior to no treatment, sham acupuncture and medication. Further, acupuncture enhanced the quality of life more than did medication.

The authors comment in the discussion section that the overall quality of the evidence for most outcomes was of low to moderate quality. Reasons for diminished quality consist of the following: no mentioned or inadequate allocation concealment, great probability of reporting bias, study heterogeneity, sub-standard sample size, and dropout without analysis.

Further worrisome deficits are that only 14 of the 62 studies reported adverse effects (this means that 48 RCTs violated research ethics!) and that there was a high level of publication bias indicating that negative studies had remained unpublished. However, the most serious concern is the fact that 50 of the 62 trials originated from China, in my view. As I have often pointed out, such studies have to be categorised as highly unreliable.

In view of this multitude of serious problems, I feel that the conclusions of this review must be re-formulated:

Despite the fact that many RCTs have been published, the effect of acupuncture on the quality of life of migraineurs remains unproven.

The public is often impressed by scenes shown on TV where surgeons in China operate patients apparently with no other anaesthesia than acupuncture. Such films have undoubtedly contributed significantly to the common belief that acupuncture cannot possibly be a placebo (every single time I give a public talk about acupuncture, the issue comes up, and someone asks me: how can you doubt the efficacy of acupuncture when, in China, they use it for major operations?).

Some years ago, I have myself been involved is such a BBC broadcast and had to learn the hard way that such scenes are more than just a bit misleading.

Unfortunately, the experts rarely object to any of this. They seem to have become used to the false claims and overt propaganda that is rife in the promotion of acupuncture, and have resigned to the might of poor journalism.

The laudable exception is a team of French authors of a recent and excellent paper.

This unusual article analysed a clip from the program “Acupuncture, osteopathy, hypnosis: do complementary medicines have superpowers?” about acupuncture as an anaesthetic for surgical procedures in China. Their aim was to propose a rational explanation for the phenomena observed and to describe the processes leading a public service broadcasting channel to offer this type of content at prime time and the potential consequences in terms of public health. For this purpose, they used critical thinking attitudes and skills, along with a bibliographical search of Medline, Google Scholar and Cochrane Library databases.

Their results reveal that the information delivered in the television clip is ambiguous. It did not allow the viewer to form an informed opinion on the relevance of acupuncture as an anaesthetic for surgical procedures. It is reasonable to assume that the clip shows surgery performed with undisclosed epidural anaesthesia coupled with mild intravenous anaesthesia, sometimes performed in other countries.

What needs to be highlighted, the authors of this critique state, is the overestimation of acupuncture added to the protocol. The media tend to exaggerate the risks and expected effects of the treatments they report on, which can lead patients to turn to unproven therapies.

The authors concluded that broadcasting such a clip at prime time underlines the urgent need for the public and all health professionals to be trained in sorting and critically analysing health information.

In my view, broadcasting such misleading films also underlines the urgent need for journalists to be conscious of their responsibility not to mislead the public and do more rigorous research before reporting on matters of health.

Back pain is a huge problem: it affects many people, causes much suffering and leads to extraordinary high cost for all of us. Considering these facts, it would be excellent to identify a treatment that truly works. However, at present, we do not have found the ideal therapy; instead we have dozens of different approaches that are similarly effective/ineffective. Two of these therapies are massage and acupuncture.

Is one better than the other?

This study compared the efficacy of classical massage (KMT, n = 66) with acupuncture therapy (AKU, n = 66) in patients with chronic back pain. The primary endpoint was the non-inferiority of classical massage compared with the acupuncture treatment in respect of the impairment in everyday life, with the help of the Hannover function questionnaire (HFAQ) and the reduction in pain (“Von Korff”-Questionnaire) at the follow-up after one month.

In the per-protocol analysis during the period between enrollment in the study and follow-up, the responder rate of the KMT was 56.5% and thus tended to be inferior to the responder rate of the AKU with 62.5% (Δ = - 6%; KIΔ: - 23.5 to + 11.4%).

The authors concluded that classical massage therapy is not significantly inferior to acupuncture therapy in the period from admission to follow-up. Thus, the non-inferiority of the KMT to the AKU cannot be proven in the context of the defined irrelevance area.

I find such studies oddly useless.

To conduct a controlled trial, one needs an experimental treatment (the therapy that is not understood) and compare it with an intervention that is understood (such as a placebo that has no specific effects, or a treatment that has been shown to work). In comparative studies like the one above, one compares one unknown with another unknown. I do not see how such a comparison can ever produce a meaningful result.

In a way, it is like an equation with two unknowns: x + 5 = y. It is simply not possible to define either x nor y, and the equation is unsolvable.

For comparative studies of two back-pain treatments to make sense, we would need one of which the effect size is well-established. I do not think that we currently have identified such a therapy. Certainly, we cannot say that we know it for massage or acupuncture.

In other words, comparative studies like the one above are a waste of resources that cannot possibly make a meaningful contribution to our knowledge.

To put it even more bluntly: we ought to stop such pseudo-research.